30 Issues: Which Party Will End Poverty?

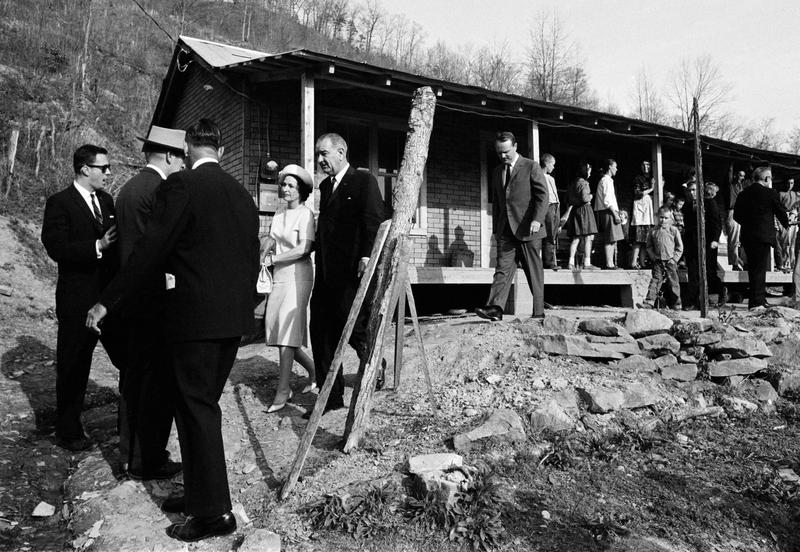

( AP Photo )

[music]

Brian Lehrer: It's The Brian Lehrer Show on WNYC. Good morning, everyone. Six days before election day and it's your money week in our 30 Issues election series. Today, Issue 28, is there a Democratic and Republican way to fight poverty? Now, on the campaign trail, you hardly ever hear the P word. They talk about middle class, working class, often the phrase working people, neither party leans into fighting poverty very much.

Yet maybe the biggest silver lining of the pandemic has been that child poverty actually declined by about half because of the Earned Income Tax Credit, the Child Tax Credit, and other pandemic income supports that the federal government established temporarily. Longer term, the poverty rate in the US had risen to around 15% during the Great Recession over a decade ago, gradually came down to around 12% by 2019, and then down to around 8% at the height of the pandemic.

Even longer term than that, according to my guess, poverty expert Christopher Howard will be on in a second, child poverty in the US was around 25%, one child out of every four back in 1993, and has been coming down generally over these past 30 years, but why? Is it from Democratic, Republican, or bipartisan policies? Why does there continue to be such a disparate impact of poverty by race? Moreover, why does the United States, one of the richest countries in the history of the world have persistent poverty at all when we're also seeing the number of billionaires go up?

With us now is Christopher Howard, Government and Public Policy professor at the College of William & Mary in Virginia, author of a new book called Who Cares: The Social Safety Net in America. Back in 2008, he also wrote the book, The Welfare State Nobody Knows: Debunking Myths About US Social Policy, and some of you may have seen he had a Washington Post op-ed just last week called Democrats aren't saying much about reducing poverty and unemployment. Why? Professor Howard, thanks for joining us. Welcome to WNYC.

Christopher Howard: Thanks. Good morning.

Brian Lehrer: Before we talk, I want to take you and everybody on an audio journey through almost 60 years of presidents and one Speaker of the House talking about poverty. This is President Lyndon Johnson in his State of the Union Address in 1964.

President Lyndon Johnson: This administration today, here and now, declares unconditional war on poverty in America.

[applause]

Brian Lehrer: LBJ in the '60s. Here's President Ronald Reagan in the '80s.

President Ronald Reagan: My friends, some years ago, the federal government declared war on poverty and poverty won. Today, the federal government has 59 major welfare programs and spends more than $100 billion a year on. What has all this money done? Well, too often it has only made poverty harder to escape. Federal welfare programs have created a massive social problem.

Brian Lehrer: Reagan in the '80s, and Bill Clinton in the '90s.

President Bill Clinton: For so long, government has failed us, and one of its worst failures has been welfare. I have a plan to end welfare as we know it. To break the cycle of welfare dependency, we'll provide education, job training, and childcare, but then those who are able must go to work.

Brian Lehrer: Must go to work. That was Clinton in the '90s. Here is President Obama in 2014.

President Barrack Obama: Hi, everybody. Everything we've done over the past six years has been in pursuit of one overarching goal, creating opportunity for all. What we've long understood though is that some communities have consistently had the odds stacked against them. That's true of rural communities with chronic poverty. It's true of some manufacturing communities that suffered after the plants they depended on closed their doors.

It's true of some suburbs and inner cities where jobs can be hard to find and harder to get to. That sense of unfairness and powerlessness has helped to fuel the unrest that we've seen in places like Baltimore and Ferguson and New York. It has many causes from a basic lack of opportunity to groups feeling unfairly targeted by police, which means there's no single solution.

Brian Lehrer: President Obama in 2014 mentioning many communities that have suffered from poverty, the solutions are complex, and that some communities consistently have had the odds stacked against them. Pretty different from former Speaker of the House, Newt Gingrich, who also addressed poverty in 2014, this is from Newsmax and argued that Republicans have had a better way to fight it.

Newt Gingrich: This is the 50th anniversary of Lyndon Johnson's State of the Union declaring the war on poverty. It's also the 50th anniversary in October of Ronald Reagan's first great national speech, A Time for Choosing, in which he outlined almost exactly the opposite philosophy. We now have a 50-year track record, when we have followed principles of hard work, low taxes, limited regulation, encouraging small business, encouraging people to learn and to get a job, it's worked dramatically.

Brian Lehrer: There, folks, is a little history tour of Democrats and Republicans in powerful positions on poverty. Our guest again is College of William & Mary Public Policy Professor Christopher Howard, author of the new book, Who Cares: The Social Safety Net in America.

Professor, can we make our way through some of the ebb and flow of US poverty policy and work our way to the present through those clips? When LBJ declared war on poverty in 1964, which so many of our listeners right now were not even alive for, which Americans was he mostly keying on and what did the war on poverty actually consist of?

Christopher Howard: When he was talking about poverty in the early 1960s, the common way about thinking about that was that it was largely localized in Appalachia. It was white folks in Kentucky, West Virginia, but there was at that time a growing recognition that poverty was, in fact, all over the place, and some of this was due to the work of Michael Harrington. If you read the rest of that war on poverty speech, you'll see a remarkably long list of initiatives that he's suggesting to tackle poverty.

Not only things that we might think of as being targeted at the poor, but he also loops in Medicare as being part of his war on poverty, changes to education, changes to transportation, even tax cuts. He's got a very broad laundry list there. For people who subsequently debate whether or not we won or lost the war on poverty, a lot of that hinges on whether they take a fairly narrow or fairly wide view about the war on poverty and what it really involved.

Brian Lehrer: The Reagan clip from the '80s that the US declared war on poverty and poverty won, in brief, what narrow view would you argue that he was taking, and in what ways was he right or wrong?

Christopher Howard: I think, in particular, he was focusing on the cash welfare program at that time, which was called AFDC, Aid to Families with Dependent Children. From the early 1960s to the early 1980s, there was a substantial increase in the number of people who were on that cash welfare program. One of the things that he did in his very first budget is that he pushed for cuts in eligibility for AFDC.

He also pushed for some cuts in programs like Medicaid and food stamps as a way of cutting back, in particular on the targeted programs aimed at low-income people. He really didn't do very much at all to programs like Medicare and Social Security, which either were created in the 1960s or significantly expanded in the 1960s, and both of which have had major positive effects on reducing hardship in this country.

Brian Lehrer: Those are both targeted at older people, whereas Medicaid can be targeted at poor people of any age and very much including children. What happened to poverty under Ronald Reagan when he made those cuts?

Christopher Howard: The poverty rate really, since the 1970s up until just before the pandemic, has basically just bounced around a fairly narrow range from about 11% to 15%. It's gone upsome in recession, it's come downsome when the economy is in good shape, but the changes that Reagan made in the early 1980s didn't have a huge impact either on poverty and they didn't have a huge impact on the welfare roles either.

Brian Lehrer: Would that be an argument almost in support of his position that all the money that was spent after LBJ in the war on poverty didn't do much?

Christopher Howard: That's certainly when Republicans took control of Congress in the 1990s under Gingrich there. They very much circled back to that argument there and put the combination of lots and lots of government spending with the fact that poverty wasn't going either up or down much at all. If you look, though, at the poverty spending numbers that they used, a very, very small piece of that was the classic welfare spending, AFDC.

A lot of that spending was on Medicaid. You didn't really hear Republicans at that time talking about how there had been improvements in infant mortality, maternal mortality, infant health, because Medicaid had been expanded particularly in the 1980s to cover more women and children.

Brian Lehrer: When Bill Clinton came into office in the '90s as we hear in that clip, he felt compelled despite being a Democrat to promise an end to welfare as we know it, one of the most famous Bill Clinton lines. What was welfare as America knew it, I guess you just described it. In brief, what changed under the Clinton White House and the Gingrich Congress in the big welfare reform of that era, and with 25 years of experience now with that law, what changed for better or worse?

Christopher Howard: There were a couple of big changes. The classic welfare program, AFDC, was renamed to TANF, Temporary Assistance for Needy Families. One change is that it went from being a budgetary entitlement to a block grant, so that helped to cap the growth in spending and keep it flat. There was also a change there where time limits were added in to the program. The general rule of thumb was no more than two years per spell of welfare, no more than five years total over the lifetime of an adult.

There were also some other changes to the program involving eligibility for recent legal immigrants that affected, not only the new TANF program but also food stamps and Medicaid. In the short run, that's where most of the money was saved by making it harder for legal immigrants to get those benefits. Since that time and even somewhat before that welfare reform was passed, the welfare roles started to drop and drop really dramatically.

There were some other things going on in the '90s that help explain that. The welfare reform is part of it. There was also some sizable expansions of the Earned Income Tax Credit that made work pay for a lot of low-income families. The economy, in general, was pretty healthy in the mid to late 1990s. Literally, the welfare population just on that TANF population dropped by more than half from the early '90s to the early 2000s. What we're left with on the classic welfare program is a very small number of families. Most welfare recipients are kids, and many of the parents are operating under work requirements there.

There are some exceptions, but there's a stronger push than usual to get the parents out and working and not relying entirely on welfare. Since those reforms, and to some extent even before that, the big spending has been going elsewhere. It's programs like the Earned Income Tax Credit, Medicaid, food stamps which is now called SNAP, that's where we're spending a lot of money that targeted just at people with low incomes.

Brian Lehrer: Listeners, we can take your calls. Is there a Democratic and Republican way to fight poverty according to you? 212-433-WNYC, 212-433-9692. If you have experienced poverty, what government policies have helped or hurt you, or anyone else with a comment or a question, no matter how you vote? In today's 30 Issues segment, is there a Democratic and Republican way to fight poverty, with Professor Christopher Howard, who's a 30-year expert on the topic from William & Mary. 212-433-WNYC, 212-433-9692, or tweet @BrianLehrer. Professor, how racially disparate are poverty rates today compared to when LBJ declared war on poverty in 1964?

Christopher Howard: Some of the data don't go back quite all that way, particularly when you're dealing with Hispanics or Latinos, but the general rule of thumb since the 1960s has been that Black and Hispanic poverty rates have generally been somewhere between two to three times as high as for non-Hispanic whites. That margin has come down, some in the last few years, but the rates are still substantially higher for Blacks and Hispanics. You can look at other measures of hardship like food insecurity and housing cost burdens, and you'll find the same story where there's real racial inequalities in all of those.

Brian Lehrer: We heard the contrasting clips of Obama and Gingrich, both speaking in 2014, the 50th anniversary year of LBJ declaring war on poverty. Did you think those two clips together perhaps distilled the Democratic and Republican approach to fighting poverty? Obama, in a nutshell, focused on communities with the odds stacked against them, and Gingrich focused on personal enforcement like requiring hard work and the benefits going to the non-poor, like cutting taxes and deregulating businesses.

Christopher Howard: Yes. On the Republican side with a few exceptions, there's been a real emphasis on enforcing work. There were the work requirements that the Republicans insisted on in the '90s with welfare. You'll also find in more recent years Republicans advocating for work requirements being connected to Medicaid or being connected to SNAP food stamps. For the Democrats, the clip there from 2014 is a little unusual because that is the 50th anniversary of the war on poverty.

That year, both Democrats and Republicans just paid more attention to poverty than they usually do before or since. For the Democrats, particularly under Obama, there is a clear pledge that nobody who works full-time ought to be poor. That is not as bold a pledge as LBJ's unconditional war on poverty, but it's still, relatively speaking, a bold pledge there. Democrats, in particular, have been focusing on working families, as you indicated at the top of the show, and trying to make sure through changes to the Earned Income Tax Credit, changes to minimum wage laws, to really try to make work pay.

What that leaves out, though, is that there are millions of people who are young or old or severely disabled, who really aren't in a position to be earning a paycheck, and the Democrats have been relatively silent about what happens to them.

Brian Lehrer: To finish this thought and a bit of this earlier history tour before we go to some callers who are calling in and actually get to the context of the midterm elections right now, since this is part of our 30 Issues midterm election series, and you've been watching this, I think you started at William & Mary in 1993, to me, maybe the biggest enduring divide between Democrats and Republicans on domestic policy, like a first principle in the culture wars, is about poverty and race.

Democrats see racial disparities in poverty as being structural, the result of 400 years of government and private sector racism, and that it's the responsibility of society, majority white, to do something about that. Conservatives, broadly speaking, see poverty as an individual moral failing, and they resent social programs that they think are taking money out of their hard-working pockets to hand it out to undeserving people who are disproportionately Black as they see it. That, to me, does a great deal to explain conservative president's elections from Ronald Reagan to Donald Trump and one of the bedrock roots of the culture wars. How much do you agree or disagree?

Christopher Howard: I think there's a lot of truth in that. I guess one tweak that I would make to that is that when Democrats talk about structural sources of poverty and they talk about legacies of discrimination, they also then talk about the structure of the job market and the labor market and say that it's very difficult for people, Black and white, to find full-time work at a decent wage and that disproportionately, the people who are struggling to make it in the job market are often African American or Latino, but that those problems also affect a lot of whites.

What they are trying to do is trying to find ways of making the job market work better. Whereas for conservatives and Republicans, there's great faith that the job market and the labor market is efficient, you just need to cut taxes and reduce regulations and a rising tide will lift all boats.

Brian Lehrer: Relevant to this history, I think, is that LBJ also launched affirmative action as we generally think of it, which conservatives are challenging at the Supreme Court just this week. We're going to do a separate segment on that later in the show, but challenging it as reverse racism with no context of who's been officially left behind for almost half a millennial. They're trying to convince the country and the court that race awareness for inclusion is the moral and legal equivalent of race awareness for exclusion, prime directive culture war stuff, and it too traces back to the personal versus structural causes of economic inequality. No?

Christopher Howard: Yes. In part of my book, I look at public opinion polling on what do you think is the main reason for poverty as individual failure versus structural reasons. Those questions don't usually get into some of the details about race and discrimination. One of the things that you see in the '90s, Americans were more likely to think that poverty was related to some individual failing. Maybe it was people being irresponsible, lazy, whatever, but as you work your way more closely to the present, you find a shift where people are more likely to say that they think poverty has structural reasons. I can't tell from those polls how much of that reflects race as a structure and how much of it reflects changes in the economy.

Brian Lehrer: Interesting. We'll continue with Professor Howard. We're going to start taking your calls, and we're going to route this now squarely in the midterm elections when we continue in a minute. Brian Lehrer on WNYC.

[music]

Brian Lehrer: Brian Lehrer on WNYC as we continue with Issue 28 in our 30 Issues in 30 Days midterm election series, is there a Democratic and Republican way to fight poverty? My guest is Christopher Howard, Government and Public Policy Professor at the College of William & Mary in Virginia, and author of a new book called Who Cares: The Social Safety Net in America. He had a Washington Post op-ed last week called Democrats aren't saying much about reducing poverty and unemployment. Why? Let's take a phone call. Danielle in Westchester, you're on WNYC. Hi, Danielle.

Danielle: Hi. I just wanted to bring this discussion to how poverty is being defined. It was mentioned that custom Medicaid did not result in an increase or a decrease in the poverty rate and so proves that government welfare programs don't have impact. Since Medicaid is for medical care and if you don't have it, you usually avoid the healthcare system, that will result in your life expectancy decreasing or your quality of life decreasing.

That won't necessarily be captured in income numbers and poverty numbers that we measure except for rare cases if you can't work, et cetera, or if you end up dying from an illness, that [unintelligible 00:23:25] poor. How do we actually measure the effectiveness of welfare programs in the manner that actually captures well-being and not just income numbers and defining poverty just as income numbers?

Brian Lehrer: Money. Fabulous question. Professor?

Christopher Howard: I think that's a great question. For a long time, we've been very fixated in this country on the standard Census Bureau measure of income and poverty and the idea that you're either below or above that line, yet there are lots of people who live somewhat above that line who still have very difficult lives. In my book, I tried to suggest that we really do need multiple measures of hardship to get a sense of people's overall well-being here and that income poverty, the way we really measure it, is just one of those. We also ought to be looking at things like, who's got health insurance and who doesn't.

What people are skipping needed healthcare because they can't afford it? What people are having to double up for housing because it's too expensive? How many people are spending more than half of their paychecks on housing? I think there are a lot of ways in which people can be stressed, a lot of ways in which people experience hardship. It's not that helpful to rely only on one measure.

Brian Lehrer: How do you measure poverty as a function of income? Because I know in your Washington Post op-ed, you talk about one way that the government measures it being inadequate and now a better way that the government measures it. Also, it's different from place to place depending on the cost of living. One of the things we talked about on yesterday's show is a ballot measure for voters in New York City this year that would have the city government report annually on what they call the true cost of living in New York City.

That's going to be different than the true cost of living probably where you are in the Peninsula in Virginia or somewhere in Alabama or pick your place. What is the federal poverty level, and how do we determine a true poverty level, even if we're not looking at quality of life measures other than income for people in different places?

Christopher Howard: Good question. The traditional official poverty line, we've had that since the early to mid-1960s. Even at that time, the people who were coming up with it knew that it was crude in some ways. It was just a decent ballpark estimate. One of the ways it falls short is in the geographic differences. In the official line, I think there may be some adjustments for Alaska and Hawaii, but the continental 48 states are treated pretty much the same.

Now, for the last decade or so, the Census Bureau has created what's called a Supplemental Poverty Measure. One of the ways that it is an improvement is that it takes into account better the taxes that people are paying or the tax refunds they're getting. It takes into account some of the benefits like food stamps and housing benefits, and it makes some more adjustments for cost of living.

Even so, you can look at other organizations, like the United Way has their measure called ALICE, I think it's Asset Limited, Income Constrained, and Employed, trying to get a sense at the people, in particular, who are working poor and those numbers for what it takes to afford a decent standard of living, not luxurious, just decent, very remarkably around the country, much more than the official government numbers.

Brian Lehrer: Let's take another call. Meeks in Brooklyn, you're on WNYC. Hello, Meeks.

Meeks: Hello. Hi

Brian Lehrer: Hi, there.

Meeks: Can you hear me?

Brian Lehrer: Yes, I can. I see you told our screener you just voted.

Meeks: Yes, I did, for the midterms, early voting. I noticed that something about the Working Families Party, which it's not something new. I was also listening to what you guys were saying, and it helped me understand what I want to say, which is all of these are measurements. All of these measurements we're trying to add more ways to measure poverty and different ways to figure out who needs what, but either way, all our measurements are always going to fall short just like the census always falls short in misrepresenting different areas.

I also think that race definitely affects the job market and other things like disability, the job market and income, but at the same time, in a way, these are value judgments because there's, for instance, someone who has certain circumstances that can't be measured on paper not involving race, disability, or anything like that, who's not making money, might just be written off as someone who's just unemployed for no reason.

The Republican Party has been thinking of impoverished people that they could have been working and earning money under the table because they had to for some reason. We can't measure all of that, so I think we need to figure out a different way to consider who gets what and how we help each person because their circumstances on paper, no matter how many categories we add, it's never going to capture the whole picture.

Brian Lehrer: Add up to 100%, yes. Meeks, thank you. Professor, what are you thinking listening to Meeks?

Christopher Howard: Part of the almost inherent nature of government programs is that they treat people as categories. They do that to some extent to make lives simpler in terms of figuring out who's eligible and how much they should get but also in some ways because of procedural fairness. In the early parts of the 20th century, there was a lot of concern about patronage politics and people who were getting relief because of who they knew, not what needs they had. Government programs are designed in part to treat people like they're in the same position. As the caller mentioned, people aren't always in the same position, even if on paper they look like that. That's where people who advocate for non-profits and charities say, that's where we come in. We tend to deal with people more as individuals. We don't have nearly the resources of government, so we're not a substitute for government, but sometimes, we're better able to deal with people individually who may have multiple issues, whereas government tends to figure out what kinds of categories they're in so that they don't get accused of favoring some people over others.

Brian Lehrer: Meeks, thank you for your call. Call us again. Now we come to the present, professor, and these midterm elections. Your Washington Post op-ed is called Democrats aren't saying much about reducing poverty and unemployment. Why? In your opinion, do Democrats have something to crow about here in the midterms?

Christopher Howard: Well, I think they do. As you mentioned at the outset, there were some declines in poverty during the pandemic, which is just remarkable to have any decline given how brutal and how long the pandemic was and how many people were kicked out of their jobs or had to work on reduced paychecks. There's a lot of good things that happened to keep people from falling deep into poverty. Then the longer run story is about child poverty based on that Supplemental Poverty Measure, the better one that the Census Bureau uses is it does look like over the last 30 years with programs like Social Security, the Earned Income Tax Credit, low-income housing, food stamps, we've made a significant dent in the problem of child poverty in this country.

Some of those programs like Social Security are ones that I think Republicans would celebrate. You can find Republicans in the past, including Ronald Reagan, pushing for the Earned Income Tax Credit, but those are also programs that the Democrats tend to support. They're also the ones much more likely to support programs like housing assistance and food stamps.

Brian Lehrer: Although the Republicans killed the Child Tax Credit that was temporary during the pandemic, and Democrats wanted to make it permanent because it did so much to reduce child poverty during the pandemic, Republicans now are talking about transforming Social Security from an entitlement that's permanent to being reinspected as part of the budget every five years to consider how to cut it if necessary.

A hardcore way, perhaps, politically speaking, to look at all of this is that Republicans do not actually care about fighting poverty because actual poor people tend to vote Democratic, and so poor people are not their constituents. Do you think is that too hardcore a political analysis that poor people are otherized by Republicans based on the party's political interests?

Christopher Howard: It's certainly true for some Republicans. I don't think it's true for all of them, but I think that for some of the Republicans, their appeal to lower-income voters is going to be more on cultural issues than on pocketbook kinds of issues. The cuts that they have proposed or have essentially brought about like the Child Tax Credit, I'm no political strategist, but I'm surprised that the Democrats haven't tried to have a standalone vote this year or make more of an effort to push for restoring the Child Tax Credit because it really did help a lot of people, not only below the poverty line but above the poverty line who are struggling with significant expenses of raising a family. There is good evidence that that expansion last year made a meaningful difference in the lives of a lot of families with kids.

Brian Lehrer: You write in your op-ed that Democrats' reluctance to campaign on poverty reduction is understandable in some ways, puzzling in others. Briefly give us some of each.

Christopher Howard: The economy in most elections is the most important thing that voters care about, but the economy's got all sorts of different parts. Right now, because of inflation, you can see why Democrats don't want to talk about that part of the economy and Republicans very much do, but in other areas like poverty, like unemployment, which has come down since Joe Biden became president, I think there are positive stories to tell as well.

Part of my article was just expressing surprise that the Democrats were completely switching off economic issues to talk about abortion or mega-extremism when I thought that they had some positive news to give voters about the economy.

Brian Lehrer: Joel in Clifton, you're on WNYC. Hi, Joel.

Joel: Hi, Brian. How are you doing? Mine is like a proposal. One of the things that I really feel like that should be covered is early childhood education is very important. We need to stem the fact that a lot of kids are borne out of poverty and their education is very low. I think investing a lot in early childhood education will reverse the trend of kids' education, so, therefore, their parents could also have their kids going to schooling where they can focus more on labor.

Brian Lehrer: Yes, it's a great point, and it's something that has worked here in New York City, where Mayor de Blasio's universal pre-K program has been so popular. So many people wound up not liking him by the end of his term, but everybody liked universal pre-K. Joel, thank you. Call us again. Professor, you said before you're surprised that the Democrats in Congress didn't offer a standalone bill to make permanent the Child Tax Credit.

I also wondered after the failure of Biden's original Build Back Better bill why they didn't consider offering a standalone program that had exactly the kinds of things that Joel in Clifton is talking about, which were core to the original Build Back Better, including universal pre-K nationally and also a national childcare system.

Christopher Howard: Yes, I absolutely agree that there are plenty of studies out there showing that on a simple cost-benefit basis, early childhood education really pays off in the long run.

Brian Lehrer: And politically popular across all kinds of lines, I think.

Christopher Howard: Yes. You can give states latitude in how they handle this, but a lot of the inequalities that we see among students as they graduate high school, those are the inequalities that were present when they started kindergarten. If you really want to get a handle on those, you really need to work with kids when they're two, three, four years old and try to give them a good start before they even begin K through 12.

In Build Back Better, there was the early childhood education, there were efforts to cap how much parents spend on childcare. There were also some important provisions there that would've given families help with long-term care, where a lot of folks these days are providing unpaid care to their family members and are feeling really stressed because of that.

Brian Lehrer: Christopher Howard, Government and Public Policy Professor at the College of William & Mary in Virginia. He's the author of a new book called Who Cares: The Social Safety Net in America. He had a Washington Post op-ed last week called Democrats aren't saying much about reducing poverty and unemployment. Why? Professor Howard, we really appreciate all the contexts you've given us. Thank you very much.

Christopher Howard: Thank you, Brian.

Brian Lehrer: That's our 30 Issues in 30 Days segment, Issue 28, is there a Democratic and Republican way to fight poverty? Tomorrow, Issue 29, is there a Democratic and Republican way to fight inflation? Brian Lehrer on WNYC. More to come.

Copyright © 2022 New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.

New York Public Radio transcripts are created on a rush deadline, often by contractors. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of New York Public Radio’s programming is the audio record.