30 Issues: How to Use Initiatives and Referendums

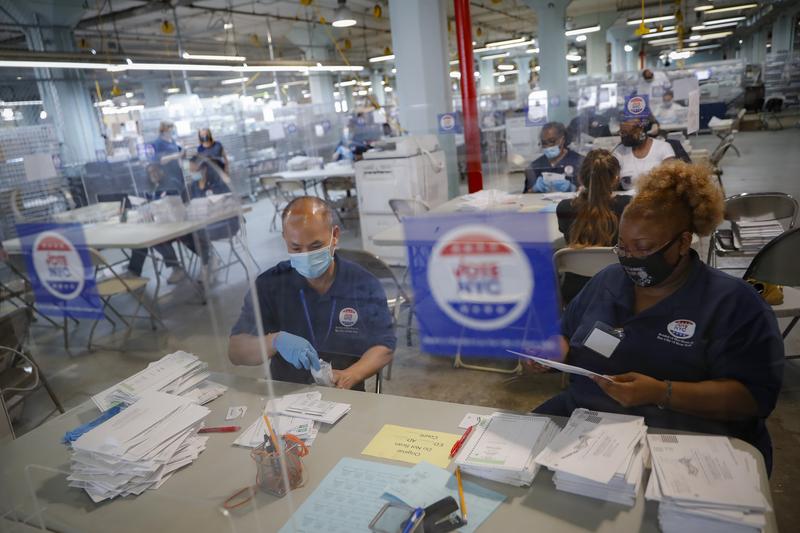

( John Minchillo / AP Images )

Brian Lehrer: It's The Brian Lehrer Show on WNYC. Good morning, everyone. We're in our 30 Issues in 30 Days election series, as many of you know. We've done stretches on abortion rights, crime, the climate, the culture wars in schools, immigration, and public health. We're in the middle of 10 straight episodes on what many of you on the phones asked for by far the most when we opened the phones on the question of what's your top issue for the midterm elections in a series of call-ins this summer. It's democracy in peril.

We're inspecting 10 different aspects of democracy in America on 10 straight shows. How much trouble is it in and how do we preserve it today? Did you hear the story on Morning Edition this morning about California voting on a ballot question to enshrine abortion rights in the state constitution? That's an example of direct democracy, making policy, not through our elected representatives, but by a vote of the people ourselves. Here in New York, this fall, voters will decide on a $4 billion New York State Environmental Bond Act, whether to create a New York City Racial Equity Office, and more.

We know that the success of the abortion rights ballot question in Kansas, where the conservative state legislature would likely have enacted a harsh abortion ban after the Supreme Court let them do it this year, in Kansas, the voters chose directly to protect abortion rights. That act of direct democracy, that single act of direct democracy, which I'm sure you've heard about, has caused anti-abortion rights candidates all over the country to start revising their positions and pretending they haven't been as anti-abortion rights in the past as they actually have.

The wave of states legalizing recreational marijuana sales started with several states that had ballot questions that bypass the legislature and legalize cannabis directly. Remember that? That was a decade ago already. One interesting thing about direct democracy votes these days, they're a flip from the past where it was the conservative movement that used it most aggressively and most successfully.

For example, one that we've talked about a number of times on the show, in 2004, when George W. Bush was barely reelected president, one of the big reasons was that conservatives got anti-gay marriage ballot questions for the state constitutions on the ballot in some key swing states especially Ohio that increased Republican turnout. Maybe the most famous or infamous ballot question of the last 50 years was California's Proposition 13, which limited property taxes much to the detriment of education funding, which depends mostly on property taxes.

That's a little bit of the history. There are pros and cons about doing these kinds of things at all. Should every populace passion be enacted into law by a direct vote when it's actually the job of the elected legislature to decide with their professional expertise and checks and balances, whether it's really in the public interest? What about Brexit? Were you for that even as a way of the Brits determining whether to stay in the EU?

Then again, with gerrymandering and other knocks on how representative or representatives actually are, maybe it's a good thing. Maybe it's the purest form of democracy with no elected middleman to peddle their special interests.

Here's the thing and here's why we're including this topic in our series on democracy in peril right now. Now that liberal ballot questions have begun to dominate over conservative ones, the conservative movement is trying to change the rules. This hasn't gotten much coverage, but I've been reading a few articles about it, and decided to include it in the series, for that reason. They're trying to make it so that ballot questions in many states cannot win anymore with a simple majority trying to make it that they need 60% of the vote. It's like taking the Senate's filibuster rule and plopping it down on every referendum that people might want to vote on.

Let's find out more with Zach Montellaro. He covers politics in the states for Politico. His recent article on this is called, Republicans Look to Restrict Ballot Measures Following a String of Progressive Wins. Zach, thanks so much for coming on. Welcome back, I should say, to WNYC.

Zach Montellaro: Thanks for having me back, Brian.

Brian Lehrer: You report that the big test cases that could set the template for this are on the ballot right now in Arizona and Nevada. What's happening in Arizona and Nevada?

Zach Montellaro: The biggest one is perhaps Arizona where there is a ballot initiative, this year, that would raise the threshold for future ballot initiatives. Right now, in many states, you need 50% to pass the ballot initiative at the ballot box. In Arizona, right now, there's a initiative to try to make it harder in the future for certain initiatives to pass, meaning you need 60%, which is a really big, big, big barrier to clear. The second one is a similar one in Arkansas, which is similarly trying to set that threshold at 60% for any ballot measure.

Brian Lehrer: Oh, I said Nevada. It's really Arkansas. It's Arizona and Arkansas. My mistake.

Zach Montellaro: That jump from 50 to 60 doesn't sound like that big of a deal, but in any state, a 60% majority is a huge margin. That would really close the path to a lot of ballot initiatives in the future if they are to pass this fall.

Brian Lehrer: It's instantly ironic, I think. They're using a ballot measure to make it harder to enact ballot measures and they only need 50% of the vote plus one to force future ballot measures to require 60%. Do I have those things right?

Zach Montellaro: Right. It's interesting too. There's some states that already have that 60% threshold, Florida being perhaps the biggest one with constitutional amendments. It just shows how tough it is to get there. We've seen this push to 60% in other states really recently as well. South Dakota tried-- I'm sorry. North Dakota tried to do this and it felt short earlier this summer.

In South Dakota, voters rejected that move to 60% over the summer primary. States have been gradually trying to push it in this direction if they have that ballot initiative process in the first place. Not every state does do this ballot initiative process. To generalize, as you go west, it becomes more prominent and along the Eastern Seaboard, it's less prominent, but the states that do have it, they're trying to make it tougher in many situations.

Brian Lehrer: How much is the Kansas abortion rights ballot measure, in particular, the impetus for conservatives to try to make ballot measures, in general, harder to pass right now?

Zach Montellaro: It's certainly part of it. The potential push we'll see for abortion ballot measures or abortion-related ballot measures is certainly part of it. It definitely predates the most recent fight over access to abortion rights in the country. The interesting thing with Kansas is that the ballot initiative there was the reverse. The Kansas ballot initiative was trying to codify restrictions to abortion rights or open up a pathway to codify restrictions at the very minimum.

What really set this all off has been in the last decade of a string of good government and/or progressive victories. Maybe the biggest driver has been Medicaid expansion. Medicaid expansion, even in red states, has happened pretty regularly through the ballot initiative process.

Brian Lehrer: You mean that part of Obamacare that Republicans opposed to allow people with the higher income threshold to get their health insurance through Medicaid, and a lot of red state governors blocked it, but you're saying Medicaid expansion succeeded by ballot questions in some of red states?

Zach Montellaro: Right. Medicaid expansion has been incredibly-- it's been one of the major ways to-- Expanding Medicaid in those holdout states has been through a ballot initiative and also independent redistricting laws, things around that as well being a commission or right to anti-gerrymandering, things like that. We've seen that in quite a few states. That has been very popular with ballot initiatives as well and that is part of the core of the backlash to it.

Brian Lehrer: You quote an Arkansas legislator who sponsored this ballot question there to make ballot questions harder to pass as saying, "Our state constitution should only be amended when there's genuine consensus among voters." Arkansas happens to be one of the most, if not the most, restrictive state in the country on abortion rights since Roe was overturned in June. They have a complete ban, even after rape and incest.

Is there a relationship between these two things, the state of abortion rights there, in particular, and the movement to make ballot measures harder to pass according to that lawmaker who sponsored this question?

Zach Montellaro: Yes. Well, again, a lot of these things predate the abortion push, but it's coming to a head with abortion law. We're going to see a few ballot measures this year on abortion rights. Michigan is probably the biggest one, after Kansas, that we saw over the summer. How this fall goes can really be an important barometer to access to ballot measures, but it's not just access to abortion rights. It's that last decade-plus of various progressive policy wins for outside groups at the ballot initiative process that's pushing people in that direction. We haven't seen too many ballot measures on abortion rights really before this year with Nevada being the big outstanding, the big exception to that. That's going to change over the next few years. What's been happening with all these other progressive winds is setting the groundwork and setting the rules of the process, so to speak, that we'll see break out over the next two, four years, where we will see a bunch of ballot measures and constitutional amendments on abortion rights across the country.

Brian Lehrer: Here's another aspect that I think hasn't gotten a lot of publicity but that I think is really interesting. That representative named Ray from Arkansas who's sponsoring this measure to make ballot measures harder also decried out-of-state big money that comes in and tries to buy changes in state law through ballot measures.

I'm taking a wild guess that he doesn't oppose dark money coming in to support candidates like himself who run for elected office and he probably supports the Citizens United Supreme Court ruling that considers big political spending a form of free speech. That's a wild guess.

Zach Montellaro: I don't know where Representative Ray stands directly on Citizens United but that's been the push and pull. Broadly, and this is generalizing but broadly conservative politicians and interest groups have supported looser campaign finance laws that have allowed for that dark money that you mentioned to perforate the system. We're speaking about federal elections both Democrats and Republicans use dark money groups to great effect but it's Republicans that have pushed forward, pushed the boundary of election law to expand it, in the first place.

These ballot initiatives do attract a lot of money from outside groups. Michigan's a good example. We're seeing a lot of money in the abortion one there from national organizations. Also just looking at California, California has a lot of constitutional amendments that are always up but they're up on everything from online gambling on sports betting to dialysis processes, and all of those have attracted tens of millions of dollars to the process. These ballot initiatives attract a lot of money on things you may not think of initially as a hot-button issue like dialysis. It attracts tens of millions of dollars.

Brian Lehrer: Dialysis on the ballot in the state of California. Here's the punchline on Arkansas for me. It's that, as you report, the movement to restrict ballot measures in that state comes partly because Republicans didn't like the fact that voters there passed a ballot measure a few years ago to raise the state minimum wage. Something tells me the big corporate money didn't want that one.

Zach Montellaro: There's been basically progressive victories in a lot of these states you would think of as red. Raising the minimum wage, it's very popular. Another one is legalizing marijuana to some varying degrees from medical marijuana in some states to full-on legalization in others. That has certainly gone through some state legislatures but where it's been very popular and where it's been getting support has generally been through these ballot processes that have opened up marijuana legalization on a state-by-state basis. That attracts a lot of money as well.

Brian Lehrer: Listeners, if you're just joining us, we've got about five minutes left with Zach Montellaro who covers state politics around various states for Politico, part of our Democracy in Peril series that we're doing in our 30 Issues election series, last week and this week, focusing today on something that hasn't gotten much coverage nationally. Zach wrote a really good article on it on Politico about how Republicans are now trying to make it harder to enact ballot measures that is direct democracy voters voting in things like Medicaid expansion, legal cannabis, raising the minimum wage, abortion rights, by adding things a 60% threshold rather than 50% plus one to make ballot measures succeed.

We're looking at that aspect of democracy in peril for another five minutes or so. Zach, do you agree with my impression that ballot measures used to be more of a conservative or right-wing political tool? I mentioned California's legendary Proposition 13 limiting property taxes to the detriment of education funding and the wave of same-sex marriage bands that were enacted that way in the early 2000s. Was it a right-wing movement that, like Dr. Frankenstein's creation, suddenly is being used against the creators?

Zach Montellaro: That's part of it. Depending on where you are in the country-- I'm a New Yorker, I'm an east coaster. We don't have a long history of valid initiatives and ballot measures in our region, broadly speaking, but, decade by decade, it really switches. If you go out to the West Coast and then further even West, some decades it's a tool of broadly conservative policies, in some decades it becomes tools as we're seeing right now with passing some liberal-leaning policies in red states.

It's, in many states, an opportunity for individual policies that may have broad support but don't have support of the party in power to get that to pass. I think we'll see a lot with Medicaid expansion and things like that. One area that I think it could become popular among Republicans, a conservative policy initiative, is election law and specifically voter ID. Voter ID, that's broadly popular with the American voters. Poll after poll says a lot of voters say that some sort of ID should be presented at the poll.

That will never pass in a democratic-controlled state. Democrats broadly think voter ID has discriminatory outcomes. We've seen some level of valid initiatives passing with some voter ID laws in place. It really depends issue by issue. The way I always try to look at it is, I think, yes, we've seen a lot of recent liberal success with ballot measures in the past. We've seen a lot of conservative success but ballot measures are what gives voters the opportunity to put something directly on the ballot even if the party in power in that state, even if it's a single-party-controlled state doesn't create that policy.

Brian Lehrer: We don't have national referenda in this country, in case anybody's wondering. We don't even elect our president by a national popular vote. We use the questionable electoral college. Look what happened in the UK, where this probably highlights the pitfalls as well as the strengths of direct democracy depending on what side you're on. That's how Brexit got passed, a national ballot measure.

I'm not sure that was a good thing compared to allowing the elected parliament to professionally debate it and be a cooling saucer. On the other hand, it was the will of the people and so that debate goes on. Here's the last thing that I want to raise, and maybe the most scary thing about this for me. I don't know if you've been following this, Zach, but part of the right-wing movement in this country is to argue that the United States is not a democracy at all. It's a republic.

The difference being that legislators, not the people, are supposed to have power in a republic. Utah senator, Mike Lee, conservative Republican is a big proponent of this, and I think it's come up very vocally in the Arizona ballot measure debate we've been talking about. This right-wing talking point that our country was not a democracy in the first place. That democracy, per se, is bad because it can go back and forth with the whim of the majority.

This even relates most frighteningly for me to January 6th and the big lie because the MAGA movement is trying to make it that state legislatures, not the electoral majority, have the final say who gets a state's electoral votes for president? Example, here's an NBC story from August. The headline is Arizona Republicans are making a case against the idea of Democracy itself. There was a New York Times Magazine article on that too.

I see that the Washington Post has a story just this weekend on potential election chaos being planned by Republicans in Nevada. It says the state legislature could step in and throw out the results in any contested state election from assembly up to governor, and install the candidate of the choice of their choice, something that is allowed under Nevada law.

If elections themselves are like ballot measures voted on by the people, apparently Nevada Republicans may try to make that state part of the Republican republic-not-a-democracy movement coming right up. We're almost out of time but I know you're familiar with the Supreme Court case in this area, right?

Zach Montellaro: Broadly there's the Supreme Court case Moore v. Harper that's going to be heard in December. At the core of that case is, who can set election policy? That case, to effect, argues that really only the state legislatures and Congress can, and that will remove the role of many courts of state courts in the process. We're at a time right now that how election laws are set could be very dramatic six months from now, very dramatically differently six months from now than it is right now.

It's one of the biggest cases, I think, that the Supreme Court has heard on elections in quite some time.

Brian Lehrer: I agree. We'll be watching Nevada as well to see if it becomes post-election day dystopia in a way that January 6th implied. All right, Zach Montellaro, state politics reporter for Politico. Thanks for the great article on this. Thanks for coming on.

Zach Montellaro: Thanks, Brian.

Copyright © 2022 New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.

New York Public Radio transcripts are created on a rush deadline, often by contractors. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of New York Public Radio’s programming is the audio record.