From 1619 to January 6th

[music]

Brian Lehrer: Brian Lehrer on WNYC. With me now is the president of Rutgers, Johnathan Scott Holloway. We'll talk about how one of the biggest universities in our area is doing in the pandemic and about his new book, The Cause of Freedom: A concise history of African-Americans. President Holloway welcome to WNYC.

Jonathan Holloway: Thanks for having me. I'm thrilled to be here.

Brian: First if I may, how's Rutgers handling in-person versus remote learning this semester?

Holloway: Oh, it's hard for everybody. I give all the credit in the world to our faculty staff and students for hanging in there, but it's hard. Most of our, virtually all of our classes are remote. We have about 20% of our students living on campus and our staff are doing just a heroic job maintaining the place.

Brian: How are you keeping cases under control? What kinds of testing or other protocols, what have you learned from other colleges and universities around that? Or what are they learning from you?

Holloway: You're right about learning. We are all paying close attention to one another and looking at different practices. Rutgers is really lucky that we were pioneers in the saliva PCR test discovered not quite a year ago. We have a huge capacity to test our students who are on campus on a weekly basis and in fact, to stay on campus, you have to be tested on a regular basis. Same thing with staff who are coming in.

Across the nation, the positivity rates are going in the correct direction, which is great. We're still in a still troubled era, of course, but I must say within the state of New Jersey, the positivity rate on campuses is relatively quite low. We are able to manage the population pretty well, but we have to be vigilant. It really doesn't take much to get a small pop-up of cases in a particular dorm.

Brian: How's enrollment because I know some colleges are doing better than others in terms of students staying with their educations and others saying, "Ah, it's not even worth it for all this trouble during COVID time. I'm going to just take a semester off."

Holloway: We're doing okay. Enrollment depends on the population. For reasons that are certainly tied to COVID, but beyond that, our international student population has really dropped down dramatically. Just getting into the country is hard.

Our out of state population for this academic year is down as well. The great news is that in terms of the number of people who have applied to Rutgers in every category, except international students, we are seeing at minimal stable, and some places fabulous growth, so I think we're going to be okay on the other side of this.

Brian: That's good, because I know some smaller schools are struggling financially because enrollment and applications are down. Last thing on this and then we'll get to the book, we have breaking news just in the last few minutes. I assume you've been notified of this, but according to nj.com, New Jersey will now allow a limited number of fans at pro and college sporting events, according to Governor Murphy. You're ready for that?

Holloway: We're ready for it. I heard yesterday that this might be coming, but we also adhere by big 10 cap. This and frankly with basketball is the place that it's the greatest concern, it's the most indoor space. I think there's only one more home game left and that's tomorrow night, maybe two for the women, I'm not sure. It's an important development, it doesn't affect us all that much in a literal sense right now.

Brian: The president of Rutgers is my guest, Jonathan Scott Holloway, his new book is called The Cause of Freedom: A Concise History of African-Americans. I'm troubled as I guess everybody who looks at these categories would be or should be, in my opinion, by the questions that you have to ask in this book, like you ask, "Who merits our history?" And you ask, "What does it mean to be human?" I want to ask you, what does it mean that we have to even ask these questions in 2021?

Holloway: Oh, that is the big question. In the introduction to the book, I canvas in this very short history, admittedly, very short by design, a series of questions. What does it mean to be human, to be American, to be a citizen and to be civilized?

If you look across the sweep of African-American experience and what is the United States, you can see at different points in time that the way people answered the question can tell you a lot about that moment. If you're asking the question, what does it mean to be human and the answer is, "Well, we would never enslave humans," but you enslaved a fair amount of people, so you have an answer there about who was considered human at a particular moment in time.

This can be extrapolated to lots of different populations in terms of how in this current moment we treat populations with very limited resources for whom English isn't the first language, who are trying to escape terrible situations in other countries. The way we answer those kinds of questions tells us a bit about who we are as a nation.

Brian: One particularly grim, but illuminating historical point that might hit home even more now because of COVID and that people have to quarantine sometimes was Sullivan Island in Charleston South Carolina. You're right, considering that the slave ships were frequently overrun with smallpox, cholera and other communicable diseases, their human cargo were often quarantined for weeks before they were released to the mainland. Can you talk about that process a little bit and why you included it in the book?

Holloway: We often think in this country, Ellis Island is a very famous portal of the population of European immigrants into the United States. It is the welcoming place and it's of great historical importance. Complicated, but that's the general sweep, but where is that space for African-Americans? That place is Sullivan Island just in the Harbor outside of Charleston, South Carolina.

As you pointed out, these slave ships were not healthy places. People came in really quite ill and infected, but their value as a commodity, as a source of labor, it was going to be limited if they weren't healthy. These waystations, these pestilence houses, became places where people would be brought back to health.

The conditions in the middle passage coming from Western Africa to the United States were horrific. This is why people got sick. They were literally-- their diseases were cured to the extent they could be, they were fattened up to the extent that they were skin and bones, their bodies were oiled in grease so the skin rashes would go away, so really was preparing a commodity for sale in the market.

Brian: Did you come to any new insights than what you had before you researched the book on this question of what it means to be human and how enslavement could have existed in the context of human to human interaction? It wasn't just in this country, it wasn't just plantation owners in the South, there was a slave trade. It involved many countries, involved countries where the enslaved people came from, et cetera, et cetera. How deep does any new insight on that run historically?

Holloway: You're right, slavery is a global phenomenon, it's been around for millennia. It is still around today in certain ways, so why focus on the United States, aside from my own area of expertise. This country is quite special in terms of the way it talks about its own sense of potential. The founding documents in this country are really quite remarkable. They are flawed, but they are quite remarkable in the history of political formations.

What does it mean that at the very heart of a country that espouses democracy and liberty and freedom, what does it mean that slavery was in the middle of that organism? You have to wrestle with that. In fact, if you don't wrestle with the centrality of slavery to understanding how this country has developed, you're not getting a full and robust sense of what this country is.

If you don't have that, then I think you start making really difficult, well, for some people, decisions about education, about healthcare, about job opportunities, it builds on a legacy of second class citizenship that has remained unaddressed to this day.

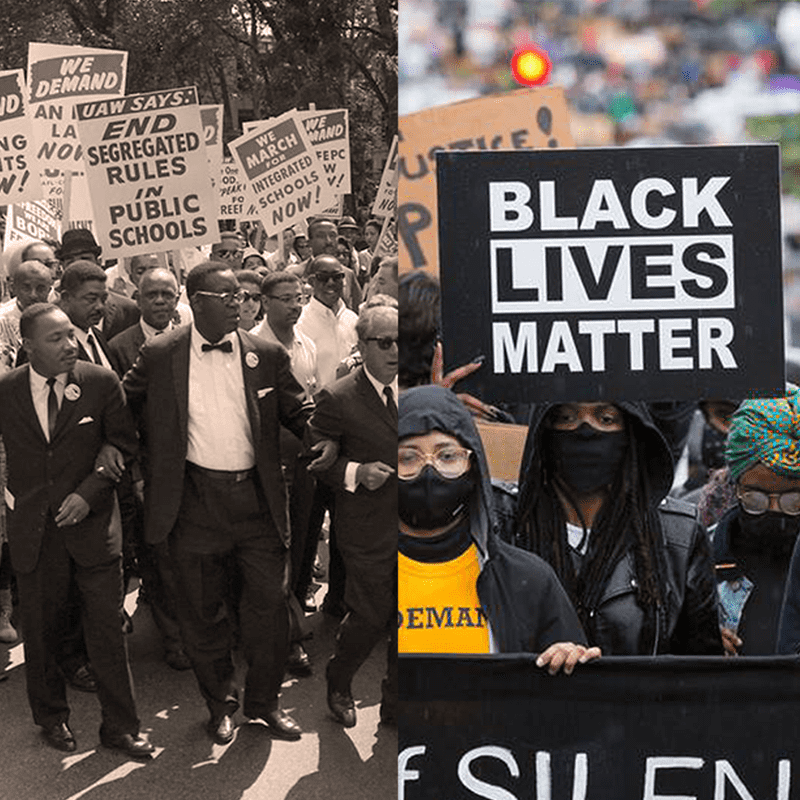

Brian: Still controversial to teach to this day. I know you have that recent op-ed in the New York Times in which you dealt with the fact that in response to the 1619 project from the Times, which put that 400 year frame from the arrival of the first enslaved person on American history, the Trump administration created what they called the 1776 Commission which was meant to put it in a softer light, I think is a fair way to put it.

Now the Biden administration has undone the 1776 Commission, but give us your sense of what that meant, and even what that felt like for you as a historian of African-America to see the Trump administration try to go down that road of softening the lens.

Holloway: As a historian, just the idea of softening history. It is a concerning process. Throughout recorded history, history is complicated and messy and difficult. Now, there are moments of triumph, absolutely sublime moments when people rise up and do amazing things, we shouldn't ignore those either, but if we ignore the difficult things, frankly, it diminishes those moments of exceptional behavior because the exceptions have risen up out of difficult circumstances.

The part of the logic of the 1776 Commission was that we, in this nation, people are teaching what I'll call lefty professors or faculty or teachers are giving children or teaching children how to hate this country.

I wrote this op-ed in the New York Times addressing things, as you already summarized, and I received an email that said, I'm paraphrasing, "Since you obviously hate this country--" Well, actually, one, never said that. Two, I love this country in so many ways, but loving the country does not mean being or professing a blind love. It's like a tough love. It's a love for its potential for the moments when it has finally met those grand ideals and a love that says we must do better.

When I think of a White House Commission that is saying, we need to have this triumphant narrative, the historian in me gets really bothered because it's actually promoting a lie. To be clear, I think this is a fabulous country, but I should be free to criticize it and critique it. That's part of what makes it such a special place.

Brian: How is your leadership as president of Rutgers reflected in the teaching or should it even trickle down? Maybe the proper role of an administrator is academically hands-off, I don't know, but you tell me, and in the context of the things we've been talking about and the things in your book.

Holloway: That's a great question. Many people misunderstand the role of presidents, especially large research universities that they are in charge of everything, we are actually not. It's very important that we keep, in my opinion, a bright line between the academic aspect of the university, which is, I mean, our reason for being, and then the administrative management of it.

There is someone who is my chief academic officer and his job is to manage the academic affairs and be faculty facing. My job is to set a larger agenda and to be essentially the spokesperson, the lobbyist, et cetera, for the university.

Having said that, right when I started at Rutgers, which is an incredibly diverse institution and all the best in exciting ways, I initiated an audit of our central administration to make sure that while we were saying the right things about, say the value of a diverse university, I don't know a university president who doesn't say that these days, but that while we were saying that, we were actually doing work supporting that as well.

Wanted to put our actions where our words were, if you allow me to flip that familiar construction. We did that work and found out that we're really good at talking about it and we're pretty good at acting upon it and there are some areas we need to do better. That's now I created a senior vice president for equity and that is the work that she's doing across this very large community to make sure there are concrete examples of how we can make sure that we are living up to our ideals.

It's important work and it's important, not from an ethical standpoint alone, which I think is also important, but we know the demographic landscape of this country is shifting. We know the democracies have made it clear where shifting and how, and it is of simply pragmatic importance, which is part of my job as the president to make sure Rutgers is well positioned, because in 10 years we'll be educating a deeply different population. If we can't understand their experiences, their backgrounds and their ambitions, then we will not be great educators. This is idealistic, moralistic and pragmatic as far as I'm concerned.

Brian: Now, we're going to go out with some music because my guest, Jonathan Scott Holloway, president of Rutgers and author now of the Cause of Freedom: A Concise History of African Americans and in that book, you close it with the lyrics from Lift Every Voice and Sing. According to the NAACP website, the song is often called the Black National Anthem and was written as a poem by NAACP leader, James Weldon Johnson, and then set to music by his brother in 1899.

We're going to listen to a little bit of the Alicia Keys version done for the NFL last September, but do you want to tell us briefly why you concluded your book with the lyrics?

Holloway: I think-- This is one of the brilliant way to end the show or this interview, thank you so much. I include it because this song captures, I think the arc in a poetic way of the African-American experience, a long sense of history, powerful challenges with difficulties, but an eye fixed on the future and the two possibilities of what this journey can mean for us. It's leaning on the ancestors, being mindful of the present and aiming for the future. It's really quite a powerful statement on its own.

Brian: Jonathan Scott Holloway, president of Rutgers and author of the Cause of Freedom, a Concise History of African-Americans. This was great. Please come back.

Holloway: Thank you.

Copyright © 2020 New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.

New York Public Radio transcripts are created on a rush deadline, often by contractors. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of New York Public Radio’s programming is the audio record.