Summer Friday: Free Speech Debate; Caste in Ameria; American Christianity and Race; James Baldwin's Impact

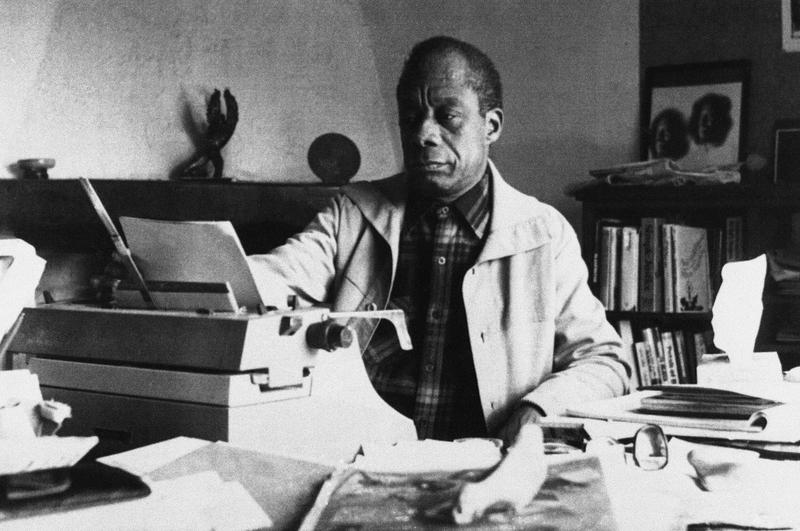

( AP Photo/Photo Pressenia )

[music]

Brian Lehrer: It's The Brian Lehrer Show on WNYC. Good morning, everyone. Today we're offering one last Brian Lehrer Show Summer Friday Special on this Friday before Labor Day. The producers and I put together a few of our favorite recent interviews with guests, including Isabel Wilkerson, Robert P. Jones, and Eddie Glaude Jr. First, this conversation about free speech, racism, and the so-called canceled culture sparked by competing open letters that were published in July. This is a dialogue between two guests, a signatory of each of the two letters. The original was called a letter on justice and open debate. It began by applauding what had caused the powerful protest for racial and social justice leading to overdue demands for police reform along with wider calls for greater equality and inclusion across our society, they praise that. Then it objects to what the letter calls forces of illiberalism and a new set of moral attitudes that tend to weaken debate in favor of ideological conformity. The letter was signed by a long list of really well-known people, including Gloria Steinem, Wynton Marsalis, Noam Chomsky, Fareed Zakaria, Margaret Atwood, Salman Rushdie, Bill T. Jones, Michelle Goldberg, Andrew Solomon, Zephyr Teachout, Nell Irvin Painter, J. K. Rowling, and others. There were also some more conservative signatories like New York Times columnists David Brooks and Bari Weiss. Weiss resigned from the Times alleging, "Constant bullying by colleagues who disagree with my views" among other issues. We'll touch on the Bari Weiss story with our two guests as well. The open letter that came in response to the one in Harper's is called a more specific letter on justice and open debate. The response letter criticizes the first one for failing to deal with the problem of power, who has it and who does not. The response letter signers are generally not famous and they say that's part of the point. The respondents see the original letter as a caustic reaction to a diversifying industry one that's starting to challenge institutional norms that have protected bigotry, it says. It says the examples of censorship or being canceled alluded to in the original letter, maybe real in some cases, but are not a trend. Now the Harper's Letter, the original one was spearheaded by the writer, Thomas Chatterton Williams, who was on this show, July 8th, mostly about something else, but we touched briefly on his letter. Here is two minutes of that exchange.

Thomas Chatterton Williams: We try to stress in the letter that the Canceler-in-Chief is Donald Trump. I think the most high profile person that's been publicly canceled in the past few years has been Colin Kaepernick. It's not just a problem on the left, but when the left is trying to correct for the very clear and present danger presented by the authoritarian right, there is a danger that the overcorrection can harden into a [unintelligible 00:03:20] that [inaudible 00:03:21] too.

Brian: I guess, in the news, the last few days has been Trump trying to identify with the critics of cancel culture by standing up for Confederate statues as well as others, but including Confederate statues. Is that relevant to your letter?

Thomas: That is completely irrelevant. Someone like Donald Trump is not a good-faith actor. He's not a good-faith participant in the kind of debate that-- Speaking for myself, I was trying to participate in and that I had imagine any of the signatories is attempting to participate in. Confederate monuments are not being canceled. There shouldn't be monuments in the United States of America to aside that fought against the country to traitors of the Republic. That, to me, is a false equivalency with the kind of thing that we're talking about here when Colin Kaepernick cannot work for having a political opinion that he expressed freely when you have people like David Shor, who get fired for simply for tweeting research. That was one of the most egregious examples that happened recently. You have the chairman of the board and the president of the poetry foundation forced to step down because their statement in support of Black Lives Matter, in support, I stress was not considered strong enough. They have lost their jobs for what was deemed to be too tap it of a response. You have the same situation on the board of the national book, Critics Circle. These are worrying examples of an authoritarian and intolerant drift in our nation's cultural and media institutions.

Brian: Thomas Chatterton Williams on July 8th. Joining us now are a signatory of the Harper's Letter that he organized, new school professor, Claire Potter, author among other things of a new book called Political Junkies: From Talk Radio to Twitter, How Alternative Media Hooked Us On Politics and Broke Our Democracy. Maybe you heard her book interview on that. The signatory of the response letter, Malaika Jabali, a public policy attorney, writer, and activist whose writing has appeared in the Guardian, Essence, Jacobin, The Intercept, Current Affairs, and elsewhere. Claire, welcome back. Malaika, thanks so much for joining us. Welcome to WNYC

Claire Potter: Thanks for having me, Brian.

Malaika Jabali: Thank you very much.

Brian: Malaika, since we played the Thomas Chatterton Williams' clip as prelude, why don't you start out and say why you think the response letter was needed?

Malaika: I think it gets at what we are really trying to demonstrate, which is that there's hardly any analysis of power when we're talking about these interpersonal grievances within "cancel culture." I think it's important to frame this more broadly in terms of what cultural institutions are we talking about. We're talking about immediate industry and a literary industry where over 80% of book publishing is white. Editorial roles are nearly 80% white. You have conservative talk radio that has now shifted into YouTube and social media spaces, but in the early 2000s, conservative radio is 90% white and that was largely due to our laws and our policy that made it easier for conservative voices to be heard. Now that we finally have some marginalized voices that are pushing back that is seen as some censoriousness. My view self-defense is not censoriousness. If you look at the actual or I would say the implied examples, because they didn't provide very clear examples in the letter. If you look at what they were talking about, these are all defenses to people who were, for instance, stereotyping Mexicans and using the N-word in a public space. These are things that deserve an open exchange of debate, which is exactly what people on Twitter and activists and journalists are doing.

Brian: In fact, to your point, let me set you up for another answer because your response letter was called a more specific letter on justice and open debate and your critique that the original did not get specific just dealt in generalities. You take some of those claims point-by-point. I will read the six points that you cite with question marks so our listeners get it. Number one, editors are fired for running controversial pieces? Two, books are withdrawn for alleged authenticity. Journalists are barred from writing on certain topics. Professors are investigated for quoting works of literature in class. A researcher fired for circulating a peer-reviewed academic study. The heads of organizations are ousted for what are sometimes just clumsy mistakes. The question marks indicate, I guess, really those things are happening as trans. Would you like to take any one of those and say why you think the Harper's Letter got the context wrong?

Malaika: Yes, absolutely. When we talk about editors being fired for running controversial pieces, that seem to be talking about James Bennett, the former- as the letter states, the former opinion editor of the New York Times, and he wasn't fired. He actually resigned because Black staffers rose up. A lot of this was happening on Twitter, which seems to be the point of ire for any of the signatory. They rose up on Twitter and said that actually this defied certain journalistic standards and norms. In the midst of a pandemic, unprecedented unemployment, brash police violence. We have a problem with repression because we're seeing it every day in our lives and against journalists, activists, et cetera, we're seeing all of this happening and so there's a call for more truth or a more military presence in the cities where these protests are happening.

Brian: That was the [crosstalk] the Senator Tom Cotton email with the Times wrath.

Malaika: Correct. It wasn't just a problem that he is having this exchange of ideas, beyond it being violent, it didn't meet editorial standards because Bennett said he didn't even read the piece and he resigned and he didn't get fired. We can talk about number two, books are withdrawn for alleged inauthenticity, that was because an author who got a $7 million book deal, apparently plagiarize a number of passages in the book. On top of that, she was stereotyping Mexicans. A free exchange of ideas is one issue, but the other is, are you actually doing your job poorly or not? People are doing their job poorly and they're having this information. It's a free exchange of false ideas, a plagiarized idea. Then that deserves some consequences. She didn't lose her book deal. She just got ratioed on Twitter. She has a $7 million book deal. Unfortunately, people like to come play these experiences with some slippery slope of fascism that we're actually experiencing on a daily basis.

Brian: Claire Potter, new school historian, why did you sign the Harper's Letter? Give us your point of view.

Claire: [00:10:59] Well, I would like to start by saying that a lot of the things that Malaika is saying, I absolutely agree with and support. I think one of the issues that the letter raises is that free speech norms support people with power and actually can exclude marginalized people. I think that's absolutely true. I think we always have to be talking about who has access to free speech and why. That's very important. That being said, one of the reasons I signed the letter is that I do not know a woman journalist today who does not shy away from stories that are going to cause her to be harassed online. Jessica Valenti actually had to shut down all of her social media and leave her platform for a period of time because she was getting so many death threats, and so many threats to her children and her family online. Actually, the toxic quality of online conversation is a huge problem for free speech. I think digital alternative media and social media, in particular, raise questions about barriers to free speech that we really haven't dealt with as a community of journalists or as intellectuals. We haven't dealt with the fact of what does it mean to call down trolls on people. I would like to acknowledge that people who opposed the Harper's Letter, some of them were viciously trolled. What do we do about the wild spread of misinformation by people who are actually committed to social justice, but have their facts wrong and have a kind of network that is going to put that misinformation out there to tons of people? I actually thought it was very important for a group of us to stand up and say we are disturbed. I would also like to say that the nonspecific quality of the letter was very, very deliberate. I'm not surprised that people read themselves into it, but James Bennett is not the only editor who has been fired for an editorial misstep. Deadspin editor Barry Petchesky was fired in 2019 for an article that he published that was controversial. Actually, the desire to grab on to one powerful man and say, all of these people are defending him is an assumption and it's a reasonable assumption. I'm sure given that it's been in the news, but actually this is a much more pervasive phenomenon.

Brian: Wants to talk to each other a little bit. Malaika, what were you thinking as you were just listening to Claire?

Malaika: I think it's hard to dispute that an open exchange of ideas and having democratic platforms are important. We wouldn't enter this field as a journalist if we did not think exchanging ideas and talking about the stories of the marginalized were important. I think the challenge with the letter is that instead of talking about Colin Kaepernick or talking about, for instance, a woman being harassed online, that was clearly focused on "intolerance in the left". I'm using that more broadly because that is an idea where we hear about what culture and cancel culture being conflated and none of those words were used in the piece, but there's a general sense that there has been intolerance on the left. If we're talking about intolerance on the left, then the examples, even if they are vague, should represent that. It shouldn't represent mostly people who do have power, who do have means who can hop to other organizations as far as Weiss' apparently seems to be reported that she's going to be going to another conservative outlet. There are people who are more than willing to welcome them. Instead of talking about Collin or talking about leftists who are being harassed because of anti-capitalism or anti-racism, or anti-imperialism, the focus is on these interpersonal grievances. I do think that that's important. I think we should have spaces where we work and we can exchange ideas. Unfortunately, if we hone it on the letter itself, it did not give any sound examples of that.

Brian: Claire.

Claire: I think Malaika raises excellent points here. I do think that's a nonspecific aspect of the letter was deliberate because we wanted our audience to actually think carefully about the things that were important to them in their lives, what they had experienced, and what they had observed and not to focus on a few very powerful people. If we look at the Colin Kaepernick example, yes, there's been a very high focus on Colin Kaepernick who has also been able to earn a very good living off of a variety of sponsorships and so on subsequent to the sad end of his football career. There have been many, many more athletes and particularly women athletes who have suffered from this kind of silencing. When you focus on Kaepernick, what you do is you actually silence knowledge about a range of less powerful people who have also suffered this. I do also like to say, I [crosstalk] Sure.

Brian: Can I jump in and ask you a follow-up question about that point. Why not separate the right from the left in this respect? Because I think part of the response letters argument is that your letter draws a false equivalency, that the censorship of- or the firing really from the NFL of Colin Kaepernick, it's so different from what might have happened to James Bennett or some of the other examples that are being asserted as censorship from the left, that it's a false equivalency. The way you defend against the right is not to also attack the left when they're not really doing the same thing. I think that's what they would argue.

Claire: I think there are a couple of positions to think about this from. One is that I think we are all, and I really mean all of us, still traumatized by the divisions of 2016 and the ways that liberals and the left fell apart around the candidacy of Hillary Clinton and brought Donald Trump to us in the first place. I think there's a huge amount of trauma about that. I think it was revived during the recent primary campaigns when, again, some of the followers of Bernie Sanders went after people like Elizabeth Warren and Kamala Harris and other people who've devoted their lives to public service. We're simply trying to make a case for themselves from the public sphere. I do think it's a problem on the left. I think that it's something if we want to displace the right-wing from our government, we actually have to deal with. I think the second thing that's worth thinking about is populism. I talk about this in my book, Political Junkies, that there is a populism that has been driven both on the right and the left by social media and the capacity, not just for ordinary people to jump in and do politics, which is great, but for organized dark web players to use that to stoke divisions on the left and the right. There may not be a moral equivalency, but there's certainly an equivalency in the dynamic and how it actually erodes our capacity to talk to each other.

Brian: Malaika, the list of luminaries on the original letter certainly made a lot of people look, Gloria Steinem, Wynton Marsalis, Margaret Atwood, Noam Chomsky, for heaven's sake, Salman Rushdie, Bill T. Jones. What do you think people should think about that list in the context of your group's letter? Because I know you had a certain take on it.

Malaika: Yes, I think, for the most part, looking at the wide array of people who signed the letter, there is obviously going to represent a wide array of reasoning behind it. The leaving in, again, painstaking it in the abstract, these norms of free exchange of ideas and democracy and liberalism. It's completely fair on the face of it when you hone in on it. I do think that examples are important because we can't talk about anecdotes if we're also arguing that this is something that's widely occurring. This is a wide occurrence and at least provide some data. Without data, all we have to rely on is trying to guess at the examples. You can say broadly that these values are important. I believe we all believe that they're important. It's easy to agree with. What's hard to agree with is how do we handle a system that has systematically oppressed a lot of the people who were the subject of the example. If you talk about, again, sending in troops, if you talk about Mexicans at the border, who were the subject of American dirt. If you're talking about a host of people who are on the left who are being deemed and tolerant, if you're looking at the people who are responding to David Shor, who are actually saying that we are receptive and we want people to listen and learn, these are folks who are experienced systemic oppression because of centuries of censoriousness, centuries of a fascist police state, and yet those voices are not included in the letter. There's another conversation that Claire is talking about that we can have, but that's not the subject of this conversation because we're talking about a letter that does not include those examples.

Brian: Is that to say that even a Gloria Steinem, even a Salman Rushdie, even a Margaret Atwood don't get it, whatever it is, on some level because of the positions of power that they've attained, in your opinion?

Malaika: Well, I don't know if they-- Who knows what each experience was? I don't know if everybody read the letter in full. Maybe they didn't think about the implications of it. Maybe they didn't think that it would get this pushback or maybe they didn't think about the specific examples and ask, and question what exactly are we debating here because you just take any logical example. If you have a conclusion and you have a premise, there has to be a B, A plus B equals C. Yes, we need these values. A, you have people who are being fired maybe for questionable reasons, but B, what's the cause of that? Are people resigning or being fired because the woke left actually caused it or did they resigned for other reasons? When you look closely, a lot of people resigned for other reasons or lost their jobs rather even.

Brian: I do see that you both tweeted about Bari Weiss resigning from the New York Times. She alleges bullying by her colleagues in support of a political orthodoxy as a central reason. Claire, I see you tweeted, "Will Bari Weiss haters now be satisfied?" Malaika, I see you tweeted, "Bari Weiss being able to quit her job on some made-up grievance and a global economic crisis is peak privileged." Claire, do you want to go first on what you think the departure of Bari Weiss? For people who don't know, she's a conservative-leaning columnist at the New York Times or was. Claire, what do you think that departure would Bari Weiss signifies?

Claire: Well, first of all, I think that Bari Weiss is an excellent example if Malaika wants data of PT Barnum's phrase, "There is no such thing as bad publicity." [chuckles] I don't think it matters what Bari Weiss does, she will always prosper through it. Part of what I was saying in that tweet is, do we all recognize that every single time you're tweeting about Bari Weiss, you're giving her more publicity and upping the number attached to her next book deal? I think that's one feature of it. I also think what Malaika is pointing out, which is oftentimes people are embedded in very powerful structures, of course, that's true of Bari Weiss. She came up through the conservative media machine, which is something I talked about in my book, that there are a series of institutes and foundations and so on, that cultivate people like Bari Weiss from a very, very early age. She started doing what she's doing in college. I think whether Bari Weiss stays at the New York Times or not, is irrelevant to anything. What I do think, and I would like to support something Malaika is saying here, these powerful institutions have very, very complicated dynamics. To the best of my understanding, there's a great deal going on at the New York Times that is roiling around, that provides a useful context for a number of these departures that we will never know anything about because HR departments aren't allowed to talk about them. I think that, but I also think that Malaika's question about data while laudable is not something that a statement of principles is likely to contain in part because you move to abstract principles to try to reset the culture, to try and reset the nature of conversation. Those of us who signed the letter absolutely knew there would be pushback. I almost never signed documents like this anymore. It really depends on whether I can handle it or not. Had I known it was coming out on the day of my book release, I might have even thought harder about it.

Brian: [laughs]

Claire: That being said, of course, we knew there would be pushback, and that is why we joined together to do it.

Brian: Briefly on this, Malaika, since you don't disagree that much, I think.

Malaika: Yes, I think it goes back to what I was saying originally is that we believe in those broad principles, but the letter didn't just talk about broad principles that said that these things were happening on "both sides." It said that it was a growing problem, that it was happening widely. When you use quantitative descriptors, and it requires some support beyond generalities. I think that is where some of the distinction is, if we're looking beyond the principles, which is what the letter asks us to do, then we want to be able to verify that. When you look at it on delve just a little bit more deeply under the surface, you see that it's not both sides, there is a lot of power wielded by conservatives in this country, a marginalization of the left, and us calling attention to it is not censoriousness, it's self-defense.

Brian: Anna in Manhattan, you're on WNYC. Thank you for calling, Anna.

Anna: Oh my gosh. Hi. [laughs] I've been listening to you for truly my entire life. [laughter]

Brian: Well, I'm glad. First-time call, it sounds like because-

Anna: Yes. [laughs]

Brian: - it'll be less of a thing next time, I promise. Go ahead.

Anna: [laughs] Thank you. I'm calling with respect to something that was said at the beginning of the segment about how these instances of cancellation are isolated incidents and not trends. I am a young person and I am calling, essentially with respect to the way that canceled culture has affected youth culture. I think that young people have learned how to be political, through canceled culture, and they've learned how to become political voices, and how to use their voices, and of activism, and how to essentially be political selves in an era of canceled culture. I think that that I've noticed, specifically on social media is has become extremely dangerous. This idea of assassination of character and not cancellation by necessity as it is often when people's voices need to be heard and this is the only way that they can have a voice. Essentially, using social media and using the idea of canceled culture or the groundwork that these kinds of movements have built and laid in order to foster a culture of fear and foster a culture of constantly dragging people down. I think that that is what I'm worried about.

Brian: Malaika.

Malaika: I think it's completely fair to be concerned about people being torn down in public spaces without us adequately listening to their views and allowing for democratic debates within reason, of course, because you know that it can go really far where people might deny slavery of a holocaust. I think we're past those types of debates or people's humanity, and what they're deserving of it. Within reason, I think that it's fair to say that that is a problem to not be able to listen to people openly. At the same time, we're talking about different things. We can talk about Twitter mobs who might attack a music artist, but you brought up political figures. If we're talking about politics, and millennials and Gen Z are facing, the worst economic crisis that previous generations have ever experienced, we're talking about institutions of power that have taken away their ability to buy homes, and to live well, and to have health care. We're in the middle of a pandemic, a crisis in which Black people are dying at three times the rate of other people. Yes, I think that these are important, but the alarmist attitude around cancel culture is a little bit disconcerting when we have all these other things that actually do contribute to people wanting to cancel, people are frustrated. [crosstalk]

Brian: Anna, quick response, Anna.

Anna: I think I just wanted to clarify, I wasn't talking about people voicing their opinions on political figures. I was more so talking about young people attacking each other. I think I was talking more about less about the actual, the things that people are saying about, about the situation right now and I completely know all of the economic crisis as someone who's- was a 2020 graduate. I think what I was talking about is the way that young people have learned to speak and learned to understand what their voices mean and not using that to attack each other.

Brian: Anna, thank you so much. I'm glad you made your first call to the show. Please do call us again. Desiree in Brooklyn, you're on WNYC. Hello, Desiree.

Desiree: Hi. I just wanted to say very quickly that I actually think that Claire and Malaika are talking about two different things. I'm a librarian. I have worked with young people and the way that people communicate with each other on the internet, on social media is a very different thing from the counseling of free discourse. Counseling somebody on the internet because you don't like what they said is a very easy thing to do. It's like synchronous as anonymous, it is part of the social media platform because people can do things so easily. They can respond so quickly without thinking, but the idea of silencing public debate, silencing discourse, silencing defense, to me, is very disturbing. I think that that is why and that's what I took from the original Harper's Letter was approaching the idea of as a community that believes in free speech, that believes in the power of individual voices, you should engage in discourse that you don't like, words that you don't like, speech that you don't like with more speech, not by silencing.

Brian: Desiree, thank you very much. Let's wrap this up with each of you saying if you think this exchange that has been taking place here in these few minutes and also in the media sphere, generally social media and professional media since the Harper's Letter and the Response letter came out last week, can all this back and forth lead to something good? Claire Potter, you first.

Claire: Absolutely. I think all free speech is actually all discussions about free speech lead to more thoughtful behavior around free speech. I would say, I not only welcome the response to the letter, but I welcome all responses to the letter. Each one of them has made me think, has made me refine my ideas, has an occasion helped me change my mind, but I actually think that citizens in the United States have to start to think about what they are supporting when it comes to forcing us into two very, very different boxes in a kind of "You're either with me or you're against me. If you said this bad thing, you're obviously a bad person." I think that's an extreme place to go that is stifling to free speech and leads us to a situation in which we are almost paralyzed in how to actually deal with the discourse is coming out of the White House.

Brian: Malaika Jabali, you'll get the last word.

Malaika: I think that we can acknowledge that we are experiencing repression there can be intolerance and we don't need additional voices that are going to continually marginalized voices that are marginalized and using broad terms that don't get into the imbalance of power that we're seeing play out in this space. When you have dozens of people who are being charged with felonies or protesting when you have a history of Black people who are not allowed to read and write in this country, if you want to take it back further censoriousness is a problem. If we only focus on the left who have relatively very little power in this country, if any, we don't have any Congresspeople, for instance, or senators who are in the left. We all run really by conservative and centrist government, we lose sight of what really matters here. I just hope that we can focus on the material conditions, material lives are lost and damaged when we use stereotypes against people who are marginalized.

Brian: Malaika Jabali and Claire Bond Potter, thank you so much for this dialogue.

Malaika: Thanks for having me.

Claire: Thank you.

Brian: Stay with us for more today. [music] It's The Brian Lehrer Show on WNYC. Good morning, everyone. What if the word racism, even the word racism, doesn't fully articulate systemic inequality in this country? What term could be used instead, or in addition to that? What about caste an artificial and rigid construction that ranks, separates, and assigns groups? Caste. I know you're thinking that's India, not the United States. According to my next guest, however, Pulitzer Prize-winning reporter and author, Isabel Wilkerson, understanding caste in the US is key to achieving racial justice. Wilkerson has already renown for the 2011 book, The Warmth of Other Suns about the history of the great migration from South to North, among descendants of people who were enslaved in this country. She was on the show at that time for that book. Her new book is being enthusiastically well-received already, and it's called Caste: The Origins Of Our Discontents. Isabel Wilkerson, an honor, welcome back to WNYC.

Isabel Wilkerson: Hello. Great to be here.

Brian: Let's go over the key terminology here, right from the start. How do you define caste and how is it different from racism or classism?

Isabel: Great. Well, caste is historically an artificial hierarchy of graded ranking of human value in a society that determines standing and respect a benefit of the doubt, often access or control of resources through no fault or action of one's own. You are born to it. Heredity is one of the basic tenants of caste as it has been known. It's basically the infrastructure of our divisions, the ranking, and boundaries that are set that determine who can do what in a society often historically. Race, however, is the metric that has been used to determine one's place or assignment in a caste system. I often describe, I think of it as caste is the bone, race is the skin, and then class, the third element that we often think of would be the clothes, the diction, the accents, the education that we can change about ourselves as we position ourselves in a society. Underneath all of this is a framework for how we are divided, how we have been divided or have been historically divided since the founding of the country.

Brian: Certainly historically divided, but people might think, well, a caste system is supposed to be rigid as opposed to the United States where at least after the Civil Rights Acts were passed, we're supposed to have social mobility for the individual. Even if that's far from true universally, it's not official like it was in India, for example, and it is the aspiration of things like the civil rights laws. Can you address caste in this country through those comparisons?

Isabel: Well, absolutely. What I'm looking at, this is a history, the subtitle is the origins of our discontent. Over the course of time, we have made tremendous progress in this country when it comes to racial justice, we've made tremendous progress with the Civil Rights Movement, for example, of the 1960s and the Civil Rights Legislation, I should say, the 1960s. Yet we still see in our current era, these efforts to-- There is the automatic attempt efforts to keep people in a certain place. When you think about caste, the word caste, when you think of what is used to hold one's bones in place when you have a fracture, a caste. When you think about the caste in a play where you have everyone in a particular role, and everyone is expected to remain in their place and it's like remaining in one's place is one of the- is part of the language of the Jim Crow system, that I wrote about in The Warmth Of The Suns. When we think about how far we have come, and yet we still have African Americans who can be going about their work, going about their day and that someone can come in and call the police on them for such ordinary things as waiting for a friend in a Starbucks, for trying to get into their own condo building, for having a barbecue in a public park. All of these things that we are seeing, not to mention, of course, the killings of African Americans at the hands of police, for often doing ordinary things of unarmed African Americans on Black people at the hands of the police for doing presumably ordinary things. These are reminders that if you think of it in a certain way, that these are the continuing shadow of what had been the originating foundation, the originating framework for where people would be in a caste system.

Brian: Throughout the book, you compare the US not just to the Hindu caste system in India, but also to what you call a more accelerated caste system that of Nazi Germany. Where does Nazi Germany come in?

Isabel: Well, what propelled me to Germany was Charlottesville. Charlottesville, where there was the contention over the statues, the Confederate and Nazi symbolism that fused among the protesters there who were protesting the potential removal of the statue of Robert E. Lee. We have battle over memory of the civil war and of slavery in our history. That is what propelled me to look into Germany, but then once I got there, actually, was looking into how they had worked through the decades after World War II to reconcile their history. Once I began to look into it and the deep research that discovered connections that I would never, ever have imagined that the German eugenesis were in continuing dialogue with American eugenesis in the years, leading up to the third [unintelligible 00:41:33] that books that were written by American eugenicists were big sellers in Germany. Of course, the Nazis needed no one to teach them how to hate, but what they did do is that Nazis actually sent researchers to study America's Jim Crow laws to see how Americans had segregated African Americans. They actually debated and consulted these laws as they were devising the Nuremberg laws. This was just gut-wrenching, incomprehensible, stunning, shocking things to discover. That is how I came to include that as a way of understanding hierarchy.

Brian: It's another way to look at the place of Jews in Germany, in the Nazi era, but before the Holocaust, as having a place in effect the caste system.

Isabel: Or in some ways assigned to a caste system, because all of this is artificial. It means that these are arbitrary distinctions that any of these caste systems are making on the basis of whatever metric they view as the deciding factor that makes one group presumably superior to another. All of these are arbitrary. All of these are artificial. That is the reason why I think that caste is so helpful for us to understand, it gives us new language, an X-ray to see what is the need, this enduring effort or impulse to keep people in a fixed place.

Brian: How much would you say unconscious bias upholds the caste system in the US today?

Isabel: Absolutely, it is probably the most powerful weapon. You might say that the caste, if you think of it as an institution, as a framework that operates beneath the surface. The fact is that the traditional classical open racism of our forefathers is not what is at work in so many things that we might see today. We don't have the same kinds of rigid as you mentioned before. The laws that say, you cannot do this, you cannot go here, this is all autonomic subconscious programming that the impulse to- and recognition that an individual who happens to be in a particular place, presumably should not be there. The messaging that we all receive as to who ranks where in our system. That's why it is so enduring and why it's so difficult to overcome, not that it's impossible to overcome, but it's difficult to fight because if you can't see it and you don't recognize it and it's not named and people are in denial about it, then it doesn't get solved. It doesn't get addressed. This is a way of understanding the subconscious, almost sometimes invisible to our consciousness, invisible to us, what is underneath, what we often are seeing among ourselves today.

Brian: Do even some attempt at white allyship perpetuate the caste system?

Isabel: A lot of it has to do with how we perceive, who should be doing what, are we actually aware of what it means to be in a marginalized group? How sensitive are we? How empathetic are we? How much are we recognizing that we all have included the messaging from the largest society? I think it calls upon everyone to be mindful of how we have all been exposed to this, so second nature as to not a question. I meant there are many women who will say, I was at a conference meeting and I made a suggestion and no one paid attention when I made the suggestion. Then when a male colleague made the suggestion, then other people at the meeting said, "Oh, that's a wonderful idea. Let's do this." That is the way that it can be subconsciously responding to the messaging about who is an authority figure, who should be in a position to be able to have the influence and authority in any particular situation. I think that it's something that everyone has to work on and recognizing that because we've all received the messaging.

Brian: Obviously, years of research went into this book and now here it gets released in August of 2020 with everything that has gone on this year. I'm curious if you changed anything or added anything in the book, down the home stretch here because of the events of 2020, or if you have a certain lands on pandemic or post-George Floyd protests through the lens of your research, that might be unique.

Isabel: That is a great question. I actually did, because of COVID-19, there was a clearly a need to acknowledge that. In fact, COVID-19 is a window into one of what I call the pillars of caste. I indicate that I compile eight pillars that are characteristics of any caste system. We saw caste unfold in some respects with COVID-19 where one of the pillars would be occupational assignment. In other words, African Americans throughout much of American history had been relegated to the bottom rank of whatever jobs. There were enslavement, of course, 246 years of enslavement followed by the Jim Crow caste system. Continuing even into the current day with COVID-19, we could see that the people who had been historically lowest-ranked in our country were relegated again to the most dangerous of physicians as we were trying to fight this thing. That means that these are people who were the ones on the frontline, stacking the shelves at a supermarket, driving buses or public transportation, delivering essential materials and packages to people, and often without the protections that they might have needed. That meant that they were most exposed to the public and then had higher rates of illness and also higher rates of deaths as a result of their increased exposure to the public exposure to the virus in their work. Their role in this allowed others to shelter in place and remain space. That became one of the ways we can see caste at work in our current moment.

Brian: Do you think that reframing-- Let me get into this way, the rave review of your book in the New York Times includes this sentence, "Wilkerson has written a closely argued book that largely avoids the word racism yet stares it down with more humanity and rigor than nearly all, but a few books in our literature." Would you agree that you were making an effort to avoid the word racism as you reframed our racist history in this country in terms of caste? Is there something about framing it in terms of caste that can lead to a more successful set of solutions and outcomes with respect to being anti-racist?

Isabel: Actually, I did not use the word racism in writing The Warmth of the Other Suns. I chose not to use the word racism because I felt that it was insufficient to capture the world in which they're into, which they've been born, and the repression that they were facing in the hierarchy into which they had been born that was repressive- that was actually a brutally enforced in the form of what we often see at the [unintelligible 00:49:10] and other violence to maintain it. I did not use the word racism, I use the word caste. Just to clarify, race is a tool of the larger infrastructure of caste. Race is the signal, it's the cue as to where one fits in a caste system. If we can see what's underneath the race and racism, then we have a better chance of being able to actually get to the core of our divisions and hopes of seeing things differently. Caste gives us new language that takes us away from the emotion of guilt and shame and blame because we have inherited this hierarchy. No one alive created it. It was not the idea of anyone who's alive today, but we now live with that, and this allows us to see ourselves differently and maybe to be able to find ways to heal from it, to heal from these divides.

Brian: Let's take a phone call. Alicia in Park Slope, you're on WNYC with Isabel Wilkerson. Hi, Alicia.

Alicia: Hi. I just wanted to share that-- Yes, I live in Park Slope and I have brown skin. I'm what next an Asian American. Something that frequently happens to me in this neighborhood, in particular, is that when I go into stores as a customer, I'm always mistaken for someone who works there. It just happens almost on a daily basis unless I'm staying inside from the pandemic. People are always asking me questions as if I work there and then when I say, "I don't work here", frequently, I'm met with aggression. This is happening from white neighbors and people in my own neighborhood. That's just one example of different ways that I'm policed by my neighbors in my own neighborhood.

Brian: Thank you, Alicia. Isabel, do you want to comment on that in the context of your work?

Isabel: That is the very definition of caste and how it works in our current era. That is exactly what I'm talking about. The idea that people are moving about their days and on the basis solely of what they look like, they are presumed to be in a particular place, a particular role that they are supposed to be in. This is autonomic, it is subconscious, and it is immediate. Those people what I'm saying is that the distinction between the old school classical racism of our forefathers, but that has now mutated into a policing and surveillance of people and an automatic desire to put them in their place. Then resistance to one standing up to actually say who they actually are. In other words, it's not allowing people to actually be who they are, it's a refusal to recognize individuals for who they actually are, and it's tremendously wearying. It is anxiety-inducing, and it actually has an impact on the health of people have to live with this every single day. There are examples of the term is called weathering, the shortening of telomeres at the cellular level. This is how deep this runs, and it's a tremendous disservice and it's tremendous stress on millions upon millions of Americans.

Brian: Alicia told some of her personal experience with this. You include personal anecdotes in the book, many of these situations occur while you're traveling on flights or at airports, would you do want to share any one of your choice that exemplifies something?

Isabel: Well, one of the ones that come to mind, obviously, as a journalist, as a reporter at the New York Times, I'm based in Chicago and I had this [inaudible 00:53:08] article I was working on. I've made the calls to all the people that I wanted to interview for that story. Everyone was excited and thrilled. I called them and set it up so no problems, everyone's excited. I was going through my interviews and it all had gone well until I got to the last interview of the day. I arrived at the establishment and the person I was there to interview was not there, the place was empty and I was told to sit and wait for him to get there. When he walked in the door, they walked in the door, this man, very harried and rushed because he was late for this appointment. When I went over to him to begin to greet him and to start the interview, he said, "Oh, I can't talk with you. I'm very very busy. I'm waiting for a very, very important appointment. I can't talk to you right now." I thought to myself, well, this is the time of the appointment, there's no one else here. It's got to be me that he's talking about. I said to him, "I think I'm here 4:30." He was late so this was clearly the time [unintelligible 00:54:10] He said, "I can't talk with you right now. I'm about to be interviewed by the New York Times." I said, "Well, I'm with the New York Times. I'm Isabel Wilkerson. I'm with the New York Times." He said, "Well, how do I know that?" I said, "Well, I'm here to interview you." He said, "Well, do you have a business card?" I actually did not happen to have any at that point because I have been interviewing all day, and I've given out the business cards. Although that should not have been the issue, most people didn't ask, but in any case. He said, "Well, let me see some ID?" I said, "I shouldn't have to show you ID, but here it is." I showed him my driver's license and he said, "You don't have anything with the New York Times on it." I said "No, but we should be interviewing right now. There's no one else here. Obviously, I'm the person here to interview you. You're expecting to be interviewed, we are minutes into what should be the interview and I should be interviewing you right now." He said, "I'm going to have to ask you to leave because the New York Times will be here any minute." The New York Times walked out the door and he didn't do the interview. I was at peace and didn't include him, he didn't get in there.

Brian: If I was the reporter who introduced myself that way, he would have never asked that question.

Isabel: That is right.

Brian: Patrick in Canarsie, you're on WNYC with Isabel Wilkerson, author now of Caste: The Origin Of Our Discontent. Hello, Patrick.

Patrick: Hello. I want to ask this question, does caste prevented Obama from being the president of this country? Does caste prevent Clarence Thomas from being a Supreme Court judge? Please, we are people who [unintelligible 00:55:55] with this racism. We wrote down the problem of us is we, Black people, look at our hospital with only down. Our children are not performing in school, we blame the teachers, we blame everything, we blame it on racism.

Brian: Patrick, thank you. Let me get a response from Isabel. Isabel, we're you ever heard the question?

Isabel: I was not able to make out all of what he was saying, but I did catch the first part. I would say that throughout American history in spite of a caste system, there have often been people who have despite the odds and with great tremendous storehouse of energy, brilliance, even and fortitude have managed to break free somehow. That does not mean that there are not exceptions to any rule. There are people who have been able to rise to very high levels in our country, and yet in some ways, the people who rise the highest become one of the most significant or instructive measures of how caste works. The higher you go, in fact, you might run into more resistance. We saw the resistance that met President Obama as he rose, there were people, there was a congressman who in open session accused him of lying. Everyone thought this is something that we do not generally see in such August convenings. This is something that does not mean that just because there are restrictions and boundaries and walls and divisions that they're not people who managed to scale them. Another example of this is, is that no matter how far you might rise, there can be in an instant, a reminder of the underlying framework and hierarchy that still percolates beneath all of this and the preeminent actor, Forest Whitaker, an Academy Award winner just happened to go into an upscale deli in Manhattan a few years ago. He went in there, came out without buying anything as many people might do. He was essentially stopped at the door by the staff who then forced him down to be searched in front of all the other customers. How humiliating for this to have happened to one of our most preeminent actors in our country. This is the way that while one might rise to great heights, there still is this underlying impulse, and it could happen at any given time, which is why this is such a corrosive aspect of how people interact even in the current day.

Brian: In our last minute, do you make policy recommendations in this book or ways to really make progress? I know you write about radical empathy as something that people should identify with and act on, it might be more at a personal level. Where do you go or is the point of the book as a historian to frame how we got here, and then policy is for others?

Isabel: I do take the long view of a historian of first trying to illuminate and shed light on where we happen to be. I've described myself in some ways as like a building inspector, and here I am going up and down the framework and the systems and trying to say, "This is what we have inherited. This is where we are." If you have a building, an old building, a thing that's being affected, it ends up being the role and responsibility of the owner of that house to figure out what is it that can be done once they now know. Once you know, then you have the responsibility to do something about it. As it turns out, obviously, in our country, all of us are the owners of this old structure. We have inherited this old structure that we did not build ourselves, but here we are; the current people to deal with it. My hope is that this will illuminate where we happen to be, shed light in corners that had not been seen before; and with the recognition that it will take all of us to find a way out of a system that has been in place for 400 years, in hopes that we can heal finally.

Brian: Isabel Wilkerson is the author now of Caste: The Origins of Our Discontents. She's going to be on a virtual book tour for the COVID era. You can see all of Isabel Wilkerson's virtual tour dates on isabelwilkerson.com. Thank you so much for spending this time with us. We really appreciate it. Congratulations on this book.

Isabel: Thank you so much. [music]

Brian: It's The Brian Lehrer Show on WNYC. Good morning again, everyone. My next guest says he grew up in a Christian denomination, founded on the proposition that slavery could flourish alongside the Gospel of Jesus Christ. From those morally dubious religious roots, Robert P. Jones grew into a religion scholar who is now CEO of the Public Religion Research Institute, which studies religious and demographic change and is author of a book called White Too Long: The Legacy of White Supremacy in American Christianity. Maybe you saw his related article in The Atlantic last month. He argues that confronting their faith's legacy of racism; by doing that, white Christians can build a better future and not just as a matter of altruism- he uses that word- but self-interest for themselves and their children, too. Robert, thanks so much for coming on with us. Welcome to WNYC.

Robert: Thanks. I'm really glad to be here.

Brian: Would you tell people what that denomination was that you grew up in that was founded on the proposition that slavery could flourish alongside the Gospel of Jesus Christ, and what the origins of that founding story were?

Robert: Sure. What's remarkable is that it's not an obscure one. So it is none other than the Southern Baptist Convention, which is to this day the largest Protestant denomination in the country. It's lost a few members over the last 10 years, but at its height, had 16 million members. I went to a Southern Baptist seminary that had over 3,000 students. It was the largest seminary in the country. One piece of this history I think that people don't know is that this was not a fringe thing at all, but was really part of white mainstream Christianity. While this is true of this kind of evangelical Southern-based group, the threads of white supremacy run really all through white American Christianity, not just among Evangelicals in the South.

Brian: You write that for yourself, it wasn't until you were a seminary student at the age of 20 that you began to realize the role that white Christianity generally has played in sustaining and legitimizing white supremacy. Can you talk about what led to that awakening in your personal case?

Robert: Yes. Well, it's quite remarkable. Especially because I was that kid who was at church five times a week- I mean, literally five times a week. From the time I was very, very young in elementary school all the way through high school and into college, I was there all the time. What was remarkable to me, certainly now as older adult looking back on it, is that I heard virtually nothing. Not only about civil rights or inequalities or injustices or the role that white Christians played in supporting segregation, supporting slavery; you heard not a single sermon, not a single Sunday School lesson out of all that time on any of that. I think, in particular, this origin story of our own denomination; that in 1845, the Southern Baptist Convention was formed really over a dispute about whether missionaries could be slave owners. The Southern churches maintained that they could, the Northern Baptist maintained that they couldn't. When they came to an impasse that really the Southern Churches forced, and then the Southern Churches broke off and formed their own convention. That was really the origins of that. That genesis story was never one that I learned growing up as a kid. It really wasn't until I was in a Baptist history course in our seminary that there was any real mention of this founding event for our denomination.

Brian: Fascinating. You described the history of not just the Southern versus the Northern Baptist, but most or all of the mainline Protestant denominations; the Northern and Southern Methodist, for example, splitting in the 19th century over slavery. But just as troubling is the story you tell of how the Methodist reunited in the 1930s, obviously way after Abolition, but in a way that still perpetuated white supremacy, you say. Can you tell us about that history?

Robert: Yes, that's really important. I think one of the key insights for me in doing the research for the book is that I think many of us were raised to think, "Oh, well, the Civil War settled the issue of slavery and all along the way, also settled white supremacy," but not at all. That even though the political issue of slavery and the moral issue of slavery was largely settled by this bloody war, the issue of white supremacy really survived. Again, not just among white Evangelicals in the South- I mean, that's not so surprising- but among Presbyterians among Episcopalians, among Methodist, as you mentioned. Many of these who have Northern bases for their membership and their organizations. The Methodist church, as you remember, yes, split like most denominations. Nearly all Protestant denominations split over the issue of slavery and white supremacy. Then got back together when the Methodist were mending the fences in the early part of the 20th century, even then when the Southern and Northern white Methodist got together. They were admitting African American churches into the fold as well into this new integrated denomination. Except for the fact that they took pains to make sure that all of the African American churches were basically segregated into one district. Usually, the way this works is the Methodist is by geography, but they broke that rule and invented this thing called the Central Jurisdiction so that they would have somewhere to put all of the African American churches. Really, this was an exercise in power. By putting them all there, they would have less influence in the other jurisdictions around the country. That's a mainline Protestant denomination among the Methodist. One more example among Catholics in New York, for example, a very similar thing happened. That in New York, there was basically one parish designated for African Americans; and for Catholic schools, there was one Catholic school designated for African Americans in New York City. Really, even as late as the '40s, where there were any mixed worshiping in Catholic parishes in New York, they were still requiring African American members to sit in the back pews and were the last to receive the Eucharist.

Brian: As you understand the history of American Christianity as a historian of American Christianity, why did African Americans, as enslaved people in this country, take on the religions of their enslavers; becoming Baptists and Methodists and Catholics, to take the examples that you've used so far, themselves in such numbers?

Robert: What's interesting-- There's a fairly simple reason. First of all, they had little choice, certainly, in the 18th and early 19th centuries when they were enslaved. It was fairly common practice for slave owners to take enslaved people to church with them. Again, the setting would be, and you could still see this in some older churches, built into the architecture. Certainly, some churches still had these slave galleries built for enslaved people to sit. Many times that's what the balconies were used for or sitting in the back of the pews, but here's one interesting thing that's happened. The book deeply grounded in history, but it's also grounded in contemporary public opinion data and sociology. One of the interesting things that that shows up is that the African Americans took this religion that they had inherited and was forced upon them by their white slave owners, but they did something very different with it. In those white churches, just one example, you would hear very little, for example, about the book of Exodus and the freeing of slaves in Egypt, which is straight out of the Old Testament. But those stories became very prominent and very prevalent among African American Christians. They intentionally took the materials of Christianity, and particularly the ones that were neglected in white Christianity, and really put them to the center of how they understood it to be Christian.

Brian: Bianca in Bed-Stuy, you're on WNYC. Hi, Bianca. Thanks for calling in.

Bianca: Hi, Brian. Thank you so much for taking my call. Just to preface my question, just for context, I'm a Black woman. I grew up in rural-suburban PA, and I went to a fundamentalist Christian school for about eight years, and then a Mennonite school and then for some reason, Christian college for two years. This question comes from the place of surviving the spaces and the communities that your guest's book documents and examines. My question is; what reparations do white Evangelicals owe the bipart Christian community and the bipart community as a whole, and what part do white Evangelicals and those who are adjacent to those communities play in helping folks like me heal from the harm they've institutionally caused? That's my question.

Brian: Great question. Robert, you do go into that in the book, don't you?

Robert: I do know. Thank you so much for that question. I think this is a very serious and central question that we're facing at this moment of reckoning around racial justice in the country. It's been one that white Christians have, frankly, been very dismissive of and haven't really been willing to take up. Certainly, one of the things I hope the book does is to lay out the history, but in a way that I think makes the question of repair and restitution and really what's required to make things right very central. I think one of the things that white Christians do, I talk about this in the closing chapters of the book; the temptation I think even for many well-meaning white Christians is to want to just reach straight for reconciliation. The formula typically goes like this; white apology and lament, plus Black forgiveness equals reconciliation. I think that's the way the equation goes in many white Christians' minds, but if you pause for a moment, you'll notice what's missing from that equation is anything about justice and really anything about true repentance, if you want to put it in theological terms. True repentance, the Bible is pretty clear, if you want to take it from an internal Christian argument, that two different places, Old Testament and New Testament [beep] to God speaking, saying; look, if you've got something between you and your brother or your sister, don't come to the altar worshiping Me. Go first and make things right with your brother and sister. The idea of repentance isn't just about lament and isn't just about admitting something or saying you're sorry, but it is about repairing the damage. I think we're clearly in place in this country where if we're honest about our history, the question of repairing the damage I think can't go unanswered. One of the things I've said is that I've been calling on white Christians to stop talking about reconciliation and just talk about repair and justice, and let our African American brothers and sisters tell us when we're reconciled. When we've done enough work and repaired enough damage to get there.

Brian: Do the denominations that you study get specific, or are there any emerging particular elements of repair that are growing us dominant?

Robert: Yes, there's some concrete things going on. One that I cite in the book is-- They're all very recent. I should say that these are very recent considerations and they're just getting started, but I do think they're going to have to be central if white Christians are going to take this seriously. But there's an Episcopalian seminary in Virginia, for example, that built within slave labor benefited from plantation ownership money also built on slave labor. So great beneficiaries of this wealth, and decided to set aside a multimillion-dollar set of scholarships that were specifically for descendants of the slave people that were involved in building the seminary and for the training of African American priests as well. That's just one small example, but I think that there's a real opportunity here. Also, it's true that many white my Christian churches are closing, consolidating. Many of them sit on very expensive property. There's old downtown churches sitting on property worth tens of millions of dollars. I think there's a real question that, as many of them are closing due to declining membership, that's an opportunity. When those buildings are liquidated, that land is liquidated, to at least think about, at the very least, tithing some of that money back as a way of-- And even that would be a drop in the bucket, but it would be a concrete step and a recognition of the damage that's been done and some real attempt at repair in the present.

Brian: Bianca, thank you for such an interesting call and prompting such an interesting response. Call us again. Phyllis in Somerset, you're on WNYC. Hello, Phyllis.

Phyllis: Hi, thanks for taking my call, Brian. I listen to you every single day from my office. I'm a Black Catholic. I grew up in Chicago and attended an all-Black elementary school and parish. Then in my young adult years, attended a mission parish in South Bend, Indiana that was established because Blacks had to sit in the back pews. Actually today, it's very well racially mixed, interestingly. You actually answered my original question with the last call but since then, I've thought of a couple more, so I'll ask one. One of the issues that I have is the images, for example, in the Catholic church; images of angels and saints, and Jesus, even, that are all white. Even when you go to many Black Baptist and AME churches, the same exists. So, we never see ourselves as Black Catholics, you never see yourself in the story. I have to say that a trip to the Vatican many years ago was very disappointing because you look up at all the paintings in the ceilings, et cetera. Let me get to my question. I'm wondering, what do you think that Christianity should do, maybe Catholicism specifically, about correcting a lot of that, and at least making people feel welcome who are already in the church if it's predominantly white?

Robert: I think this is a really great question, and I think it goes directly to the different ways in which white supremacy, frankly, gets embedded into Christianity; both Protestant and Catholic. While I think Catholicism is much more rich in terms of imagery, and so you see a lot more icons and statues, those sorts of things than you do in the Protestant situation, it's even more important I think in that setting that the images of Jesus, the images of angels; that they reflect the diversity of humanity. Just a couple of weeks ago, there was an evangelical theologian that very seriously was arguing on Twitter that Jesus was white. Not just a fringe person, it's a pretty mainstream evangelical author and pastor. That idea was really central to the way that Christianity was melded on to this idea of white supremacy. I should clarify that when I'm using the word white supremacy, I don't just mean violent extremists like the KKK. What I'm meaning is a system, something that's less exotic and also closer to home and more insidious, I think. That is really a commitment to the way that society is organized to benefit white lives at the expense of Black, brown, and Indigenous lives. For most of our country's history, that has been the way that society has been set up, and the church was complicit in that set-up and it was reflected even in the church's own symbols. I think telling a new story about who we are, how we understand ourselves to be Christian; and if we take just seriously the humanity of Jesus, for example, and even if we just read the Bible fairly literally, Jesus wasn't from Europe. He was from the Middle East. So this idea that Jesus was white or European, I think is a great myth that's come down through the portraits of white Jesus hanging in Protestant churches, statues, and icons in Catholic churches. It's definitely something that's got to be rethought because it is a representation of racial dominance mapped onto Christian theology.

Brian: Phyllis, thank you so much for your call. Please, call us again. To your point that white supremacy isn't only perpetuated with a sort of KKK mindset; to me, one of the most striking findings of your studies that you report in the book is that you say that many white Christians think of themselves as people who hold warm feelings toward African Americans, while simultaneously embracing a host of racist attitudes that are inconsistent with that assertion. We're going to run at a time very soon, but can you describe very briefly both sides of that; the attitudes and also the self-perception of warm feelings?

Robert: One quick example is for white evangelical Protestants, which is the world from which I come, that if you ask about on survey- these are contemporary public opinion surveys- you ask about; do you have warm feelings toward a bunch of people groups, and you list African Americans, white Evangelicals score- one of the highest scores, they score very high on a question like that; feeling warmly toward African Americans. If you ask a different set of questions that are about structural injustice, that are about holding other racist attitudes, [unintelligible 01:20:13] Confederate symbols, about the treatment of African Americans in the criminal justice system; if you ask those kinds of questions, Evangelicals also score among the highest scores on those kinds of questions. I've put together in the book and under the umbrella of, call it a racism index, they also score the highest there. These two things can be simultaneously true; personally warm feelings toward African Americans, while holding a whole host of other attitudes. Just two examples to give you the flavor of this. White Christians, for example, on the issue, coming right out of the murder of George Floyd by police, is they're nearly twice as likely- if you compare them to religiously-unaffiliated whites, so just Christian whites versus non-Christian whites- they're nearly twice as likely to say that the killing of unarmed Black men by police are isolated incidents rather than a pattern of how police treat African Americans. On the Confederate flag, if you take the same two groups, white Christians are about 30 percentage points more likely than religiously-unaffiliated whites to say the Confederate flag is more a symbol of Southern pride than a symbol of racism. You can multiply this survey- every survey question over question. What it really boils down to is that white Christians in the country have a very difficult time seeing anything around structural injustice or structural racism in the country. At the same time, they think, "Well, I'm not personally prejudiced," but at the same time, hold a whole host of attitudes that really are about rendering structural injustice invisible.

Brian: To wrap this up in the context of this election year, I saw you wrote an article in The Atlantic last year called The Electoral Time Machine That Could Reelect Trump that pointed out how overrepresented white Christians are in the electorate. For example, in 2016, white Christians were 43% of the US population but 55% of voters. Also, as you broke it down, white Christians were the only white group that voted in the majority for Trump. White Jews did not, white Muslims did not, white-unaffiliated did not. Now, of course, that was all before the events of this year; with the pandemic and the racial justice protest movement. How do you see that shaping up for this year? Then we're out of time.

Robert: Well, I think this is really worth noting; that the big divide among white Americans today, one of the sharpest divide is really between white Christians and everyone else among whites. In fact, it wouldn't be an exaggeration to say since Reagan, if you wanted to describe the American religious landscape, it is that white Christians vote majority for Republican candidates and everyone else; both majority- so non-religious whites, like you said, whites who identify as Jewish, Hindu, Buddhist, any other thing- tend to vote for Democratic candidates. That's the shape of our politics. I do want to point out that we get that shape of our politics really because of an issue around race. The two parties that we have today are really organized from the energy around the Civil Rights Movement. When the Democratic Party became the party of civil rights in the mid-1960s, there was a white Christian flight from the Democratic Party to the Republican Party. Today, the Republican Party is about 70% white and Christian, and the Democratic Party is about 30% white and Christian. That cleavage, which has gotten larger over time, I think is one serious way of understanding our current dynamics today. And that when we see Trump doubling down on Confederate monuments, Confederate flags, that kind of thing, how you can understand, given this history, given what the attitudes are, you can understand how that's actually not driving folks away from President Trump. In fact, when we've gone back in the field to ask about these underlying issues about Confederate symbols, about the criminal justice system, we see very little movement, even after all these protests, among white Christian groups.

Brian: Robert P. Jones. I guess if you have a common name like Robert Jones, it's good for the sake of Google searches to include the middle initial. Robert P., as in Peter Jones, CEO of the Public Religion Research Institute, which studies religious and demographic change, and author of the book; White Too Long: The Legacy Of White Supremacy In American Christianity. Thank you so much.

Robert: Thanks for having me.

Brian: Brian Lehrer on WNYC. More to come. [music]

Brian: It's The Brian Lehrer Show on WNYC. Good morning again, everyone. With us now; Princeton Distinguished University Professor, Eddie Glaude, who has a new book called Begin Again: James Baldwin's America and Its Urgent Lessons for Our Own. Professor Glaude, it's always great to have you on. Congratulations on the book and welcome back to WNYC.

Prof. Eddie Glaude, Jr.: It's a pleasure. It's always great to talk with you, Brian.

Brian: I was wondering if you could start with your professor's hat on, I guess, at kind of a James Baldwin 101. Because many listeners have heard the name, know that he's a giant in literary and other ways mid and late 20th century, but not that much more. Where would you start to introduce the totally-uninitiated to who James Baldwin was and why he was and remains important?

Eddie: First, I would say he was born on August 2nd, 1924, passed away December 1st, 1987. Born in Harlem and born to parents who migrated from the South and wasn't in Sugar Hill. He grew up in a poor side of New York City and that shaped how he saw the world. Was a child preacher and was seen as precocious, in some ways. Struggled with his sexuality in his early years and struggled with his father, but then realized that if he stayed in the United States he would, as he put it, he would either kill someone or be killed. So, he decided to leave and he packed up and went to France, and there engaged in this extraordinary effort to make himself into a writer. He did so by writing this extraordinary book entitled; Go Tell It on the Mountain, producing essays that later were collected as Notes of a Native Son, and became in some ways, Brian, one of the most insightful interpreters of American life from its underside. I like to read him as a figure who is an inheritor of Emerson, but he brings Emerson across the tracks. Baldwin lived long enough to participate in the Civil Rights Movement, found himself not only raising money but also risking his life. In one biography, he's actually said to have joined CORE, Congress of Racial Equality; and SNCC, the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee. He lived long enough to see the assassination of Medgar Evers, and Malcolm X, and of course, eventually, Dr. Martin Luther King. In some ways, the death of King; he fell to pieces. He collapsed. Actually tried to commit suicide in 1969, one of many times actually, and found himself trying to come to terms with America's latest betrayal. Only to take his last breath in Saint-Paul-de-Vence in France, and gave us over 7,000 pieces of writing. One of America's amazing, amazing artists.

Brian: Let's dig in more on that period you were just talking about, I guess before and after the death of King, but in that period. Because you write about that time between two of his major works; The Fire Next Time in 1963, and No Name In The Street in 1972, as a period when Baldwin changed in some important ways. A period you call the after-times. Can you talk a little bit about that term, and what James Baldwin was experiencing in those years?

Eddie: Yes, Brian. After-times, I take that phrase from Walt Whitman's Democratic Vistas. Whitman is trying to figure out what the country is doing after the carnage of the Civil War and the collapse of Reconstruction. He sees the Gilded Age on the horizon. That the country is making changes, is moving, but it's lost its soul. It's kind of a period of interregnum where something is collapsing, an old world is dying, a new world is trying to be born, but the ugly forces are arresting substantive change. Baldwin's after-times is really, you know, the country had turned its back on the Civil Rights Movement. You saw that when they killed what he called- he described King as the Apostle of Love. Baldwin had seen the idealism of the young people that he encountered at Howard who were foot soldiers in SNCC, who risked everything to change the country non-violently. He saw their eyes darken, how they got enraged, how a kind of realistic politics took hold, where they left aside the moral question and understood power as the principal object of concern. He saw the country literally turn its back, betray its ideals, turn its back on us again. So, he had to try to figure out how to pick up the pieces. He collapsed, trying to figure out what to do. He had to, in some ways, leave the country again and ended up in Istanbul in order to offer a language to describe the moment of how we might endure this moment and still be able to imagine America otherwise.

Brian: Do you see today as after-times in ways that are parallel to the late '60s and early '70s for Baldwin, maybe after Obama to Trump, or in any other way?