Labor Day Special: Women at Work; Dr. Anthony Fauci; Michele Harper; Essential Workers

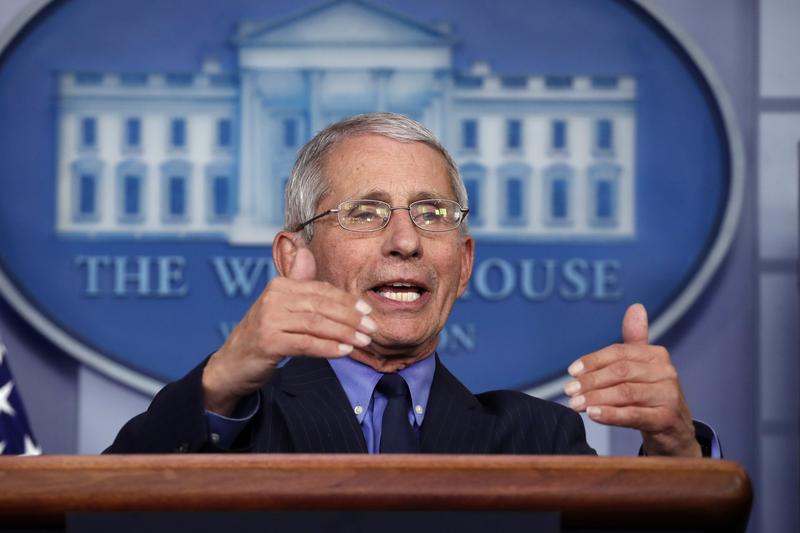

( Alex Brandon / AP Photo )

[music]

Brian Lehrer: It's The Brian Lehrer Show on WNYC. Good morning, everyone, and happy Labor Day. Today we're offering you a Labor Day Special as the producers and I rest from our labors. We hope you enjoy the chance to catch up with some of our favorite recent conversations, including this one, labor-oriented, with Jennifer Palmieri, who is the Director of Communications for the Obama White House, and Director of Communications for Hillary Clinton's 2016 campaign. She joined us in late July to talk about the need for women in the workplace to change expectations, not just live up to those set by men so long ago. You'll note this was before Joe Biden announced his VP pick. As you'll hear, that's a decision she endorses. [music] Joining me now is Jennifer Palmieri, a familiar face to those of you who watch a lot of politics on television. She served as communications director for the 2016 Hillary Clinton presidential campaign and was also the White House communications director for President Obama. Now she's an author of a brand new book called She Proclaims: Our Declaration of Independence From a Man's World. Jennifer, great to have you with us again, welcome back to WNYC.

Jennifer Palmieri: Thank you, Brian. I'm really happy to be with you.

Brian: Your book begins with a nod to the signing of the Declaration of Sentiments; the 1848 manifesto that described women's grievances and demands, written primarily by Elizabeth Cady Stanton. It called on women to fight for their constitutionally guaranteed right to equality as US citizens and independence from men. You write that "We are also at a time today, where women need to declare their independence from men." Want to start there and talk about in what ways you mean independence.

Jennifer: My realization was that as far as when there's a calm in the world, for decades, we've made a lot of progress, and then we seem to sputter out. We keep hitting the same plateaus the last three decades, in particular. Obviously, I experienced that in Hillary Clinton's campaign, but you see it in business. In the Fortune 500 CEOs, only 7% of them are women. We have 75% of Congress, is still men. At some point, you say, "We're just not doing this wrong. Women are not doing this wrong, we don't have anything left to prove. There's something else going on here." I think that following a man's path, which I believe we did after women won suffrage, had the right to vote, used that as a tool to work our way into both politics, and the professional world. I experienced this partly with the Clinton campaign, following a man's path can only get you so far. I wanted to go back and learn more about suffrage, that fight because I felt that was the last time in America that women came together to try to advocate for their rights, and what can you learn from it? I learned that when women come together and believe in themselves, even though they don't have any power, the power of their voice, the power of the action can affect real change. You also learn that there's a troubled history there too when it comes to race. When white women are not good allies to Black women, to Black Americans overall, that holds back progress for everyone. Those are the things that the book tries to explore.

Brian: What did you mean just now, if I heard you right, that the Hillary Clinton campaign followed a man's model?

Jennifer: All 45 of our presidents now, have been men, so we have a image over our head of what that looks like. You have a certain bar you have to reach. We think our male leaders, there's a certain way, there's certain timbre to their voice, there's a way they stand, there's the strength that they project, there's strength that they project in terms of being the commander-in-chief. All of these things we have internalized at this point for the country itself, for close to 250 years. As individuals, we have our entire life. One of the things I ask people to do in the book is, imagine what it would be like for men if women had been in charge from the start. If all of our presidents had been women, and a man ran, that would be very jarring to us. I think that that man might try to adapt himself to behave more like a woman because even though he knew he was different from a woman, he saw that the women were the ones with all the power. This is vice that Hillary found herself in. The women that ran in 2020, I think things progressed a little bit. We had adjusted in some ways to seeing women in those roles. Even though 2020, it's a very modern world, when you consider these things from the scope of history, it's a radical thing for a woman to be in charge. Clearly a radical thing for a woman to be in charge of the United States. I felt that, in my own career, I've never felt a man tried to hold me back. I have had good male mentors all along the way. Still, the men I worked with rose faster than I did. Still, I didn't reach certain echelons, and I looked around and saw other women also plateauing. I used to think I was doing great in a man's world. Then I realized, I'm doing great propping up the man's world, what I'm doing is making it run well for them. We keep producing generation after generation of the majority, the gross, huge majority of positions of power in this country, being held by men. My realization was I'm perpetuating this. It's not just blocking women, it's blocking all people of color from getting the power they deserve. It was a radical realization I had, and that's why I was compelled to write the book.

Brian: Does that pertain even to your job as White House communications director, a very prestigious position for President Obama or communication director for the Clinton campaign, similarly so because in the case of Obama anyway, you were out there representing a man, rather than being the person in power, or how would you say?

Jennifer: I was 10 years older than the guy that had the job before me. That's what I mean. I got the job about 10 years older than the guy who had before me. We can rise, but--

Brian: Took that long.

Jennifer: Yes. By the way, he's the one who recruited me to come to the White House. He was a very good colleague. He was very good to me. He made sure I came in as his deputy. He made sure that I had a good entry. He brought me there. I got the job as communications director, partly because he was such a big supporter of mine. This man was really helpful to me, but still, he rose faster. Is he really that much better than me that he deserved to have the job 10 years ahead of me? No. No, he's not. He would say the same. He would say the same. The thing that, the reason, why I called the book, She Proclaims, and I have a declaration, it's because I think, as women, we have internalized so much. We expect to do worse than the men. We expect it. Partly to protect ourselves so that you're not disappointed, you brace yourself for not doing as well as them. That's just crazy at this point. What I realized was, wow, we don't hold any part of the Congress. A huge majority of Congress is still men. Business and business leaders we're just not making any progress. It is not that women are not talented enough, or are not working hard enough. I think we are buying into some of the premises of the man's world. A place where you feel undervalued, can't reach real power, and doubt yourself, is not your destination. That's not where you meant to be. What I try to get at is what are the things that, the biases, and beliefs, and behaviors, we have in our own head, that hold us back. The chief among them, in my view, is believing that women are in competition with each other, women are in competition with all marginalized people for a limited seat of power, and a limited amount of success in the world. It's when we pit ourselves against each other, we're buying in. Fundamentally, what you're doing, is you're buying into the notion that you don't belong here, because I had to sneak in I don't really belong here. If that woman succeeds, I fail. I can't succeed as well. What I've done in my own life in the last several years, is just to banish that thought from our heads, support other women. I find there's sociological research that proves it's more women in the workplace, begets more women in the workplace. More people of color in the workplace begets more people of color in the workplace. When you band together and advocate for each other, that is when the lid comes off, and everyone is able to have more access to success and power. I don't think anybody looks at the world today and thinks it's great in America. I know, there's a lot of white men that feel that same way. There's a lot of white men I know that want women to do better. I'm trying to get at what are these obstacles that still remain, and the things that are in your own power you can change?

Brian: My guest is Jennifer Palmieri. She was Hillary Clinton's campaign communications director in 2016. She was President Obama's communications director in the White House, in his second term. She's the author now of the book, She Proclaims: Our Declaration of Independence from a Man's World. I should mention that she is now president of the Center for American Progress Action Fund, as well as the author of She Proclaims. Let's take an example from the book, or another example, you write about the notion of people-pleasing, how that's a female tendency, and how it affected your job as a communications director or a communication staffer, or maybe before that, and made you sometimes bad at your job, I think you say. What's an example?

Jennifer: I hope this interview is not an example of that. I think that I speak more forthrightly now. When I would do cable television hits, and I was Barack Obama's communications director, I was terrible at them because what happens in a cable news head, particularly when you're representing a politician, is that the first question is designed to throw you off your game. The first question might be a little bit snarky, it probably has a premise in it, that I don't buy into, but I would do it. In an effort, even though I knew that the news anchor was trying to throw me off my game, and trying to have an aggressive stance coming into this, I would still try to find something in the question that they'd asked me, that I could agree with, in an effort to seem reasonable, and to please the person I was speaking to. By the way, I train people on how to do media, it's something you're never supposed to do. You are never supposed to buy into the premise of the question, but I would immediately do that in an effort to please the person that I was speaking to, and to seem reasonable to the audience that I was addressing. Then, I would get tongue-tied because, and this is true, not just when I was on television, but also in meetings and any kind of professional setting, and I think that a lot of women can relate to this, I would have two conversations going on in my head the whole time. The first thought that would appear in my head is, "Here's what I think." Then, the second thought is, I would imagine how much what I was going to say was going to be challenged. I would only speak after I could reconcile what I believed with how I would be challenged, and know that I can defend it. I would hum and haw. I would get a little tongue-tied. I may be not an effective communicator, even though it's [unintelligible 00:13:31] communications director. This is something in the course of the last book that I wrote. It's called Dear Madam President: An Open Letter To The Women Who Will Run The World. It was through that process and advocating for the beliefs that I held and articulated in that book, that I learned you have to shake that other voice. I came to the conclusion that I was censoring myself. For a lot of the time, [unintelligible 00:14:01] , in a professional setting, I was not actually saying what I believed. That's not just true of me. I think that's true of a lot of women. You think, "This is a powerful deal. You are not saying what you believe, and your voice, when you do use it, and you put it out in the world, it makes a difference." I have a chapter about this, and that's one of the things I tell them, it's, speak forthrightly. Do it particularly if you're going to say something you know a woman isn't expected to say, that's what we need to hear. I think we need more perspectives in the world, not [unintelligible 00:14:34] . We need to hear different things, different solutions. Your perspective is going to be different than someone else's. Also, I just catalog in the book all the generations of women who were silenced, didn't have that opportunity, and we owe it to them to speak as well.

Brian: I think a caller would like some advice from you.

Jennifer: Let's hear it.

Brian: Shania, on Long Island, you're on WNYC with Jennifer Palmieri. Hi, Shania?

Shania: Hi. How are you?

Brian: Good. How about you?

Jennifer: Hi, hi.

Shania: Hi. I was looking for some advice actually because recently, I was passed over for a promotion by someone that I'm pretty aware that we don't work at the same level, and I also even trained them in instances, but they got the promotion over me. I can only attribute that to him being a white man and myself being a woman of color because, on paper, there really is no comparison between the two of us. I'm just calling to get some advice from you on how to approach a situation and just not be bitter or angry about it.

Jennifer: [laughs] Oh no, couldn't do that, couldn't possibly be angry about it, any of that. You have a right to be angry, but it is a professional setting. This is what I am always trying to think of, Shania, is, how can I be heard? How can I position this in a way that the man is going to hear my argument, and not just shut down? If I say, "The white man got the job and not me," or, in your case, "White man got the job and not the woman of color." I find a lot of times, white men will get jobs over women of color because people say, "He just seemed like a better fit." Of course, he seemed like a better fit, right?

Shania: That what I got, yes.

Jennifer: Did you really? Did you really get, "He's a better fit"?

Shania: Yes.

Jennifer: That's perfect. Yes, a classic. Of course, he's a better fit. Of course, he's a better fit because we're still living under power systems that were put in place, and it's not anybody's fault who's on the earth today, but they were put in place hundreds of years ago. This is important. They were built to accommodate men, and they were built to value the efforts of men over women. That is why the United States women's soccer team, which is the winningest national team in American history, has to sue to get paid what they are worth. This is what I recommend to you, you can say, "I know that you said he was a better fit, but here's something I want you to consider. I might do the job differently, but maybe that's what's needed here. This is the experience that I have, particularly if you're training people, the experience I have is, I really make this place run well, and be a good colleague for everyone. Consider this, that's what you might want in a leader." Part of the problem that happens here, is that women, we make the world run, for sure, but men are still running the world. We have to identify the good things that we do well, as you just said, about how you train people, and make them valuable. Make people appreciate how the world can't run without that, how your business, or whatever your institution is that you're working, can't run without that. Lean into the fact that it's going to be a little different. It might be a little different if I did that job, but I think that that could be a strength. There is a whole bunch of research you'll see in the book. I just have references to places where you can find out more about this. The more diverse a workplace is, the more successful it is, the more money it makes if it's a money-making entity. It's just a fact. That's the conversation I'd recommend you have. [crosstalk]

Brian: Shania, I hope that's helpful. Call us again. Emily, in, is it Olivebridge, New York? You're on WNYC. Hi, there?

Emily: Hi. I work in film production. I'm an aspiring producer. I just keep seeing, as I work my way up, so many women holding themselves back, waiting to gain skills. Meanwhile, I see all these men leaning into situations where they actually have no idea what they're doing, putting themselves in positions of power over a bunch of people who are subjected to their lack of knowledge. Meanwhile, women who know much more than them, are working below them and holding themselves back. I was just wondering if that was a pattern that you also saw, that you felt like women were maybe conditioned to wait and try, just that whole concept that I keep seeing in the film world particularly.

Jennifer: Totally.

Brian: Jennifer, it's one of the big ones, isn't it?

Jennifer: Yes, it really is. This is true. There's a lot of reasons it's true. I know that your industry, I've had little exposure to it, it is really hard for women, even worse than politics. What you've identified is a phenomenon that happens across careers. We judge men based on their potential. This is also a sociological research thing that's been proven because, think about this, we've seen their story play out time and time again, and we recognize it right away, "Oh, he's an ambitious young man. I can totally see he's going places." Women have to prove their record of accomplishment in order for people to buy into them. The way that translates into politics imagine, are, at first, Beto O'Rourke. He's a great guy, I'm sure he would have been a great president. He's a good public servant, and I won't take anything away from him, but people immediately fell in love with that guy. We recognized him right away. He looks like Bobby Kennedy. Amy Klobuchar, Elizabeth Warren, took a long time. They got traction at the end, but it took a long time for us to buy into them, we have to earn it.

Brian: Pete Buttigieg.

Jennifer: Pete Buttigieg? Pete Buttigieg is the exact same thing. Pete Buttigieg and Beto O'Rourke broke out really early, and we just fell in love with them right away. Again, not to take anything away from them, that would not have happened to a 37-year-old woman who's a mayor of a small city, there's just no way. Yes, you're right, that is what happens with women, and that's what we have to shed. There's a reason for it. We have internalized all these examples in our own lives that tell us we don't value women as much, and that women have to prove themselves more, but it's just not true. Now, we are holding ourselves back. When we don't assert ourselves and don't say, "I'm going for this," then we're propping up-- This is the realization I had, I'm propping the system up. Me waiting patiently for things to get better for women, or waiting until I have enough skills, is hurting myself, and it's hurting other women. It's hurting all marginalized people. You just have to go for it. I'm going to tell you one anecdote that shed some light on how men and women think about this differently. During Me Too, a guy friend of mine, really good guy, works for Hillary, super progressive, all that, he said to me, "You know what? It never occurred to me that women go through their life, every day, feeling fear." I was like, "What?" He was appalled at himself that it hadn't occurred to him. I thought, "God, if you don't know what it's like to feel fear, of course, you'll walk around in this world thinking it was made for you. It was made for you. Of course, you're willing to take risks, and be ambitious, and jump out ahead of yourself, and be like, I know I can do that because you've seen generation after generation after generation of men doing that." You know what? For women in America today, this is our job. Our job is to be that generation that says, "I'm just going for it even though, a year ago, I thought I didn't have enough experience. I know I do," and you have to show with what that looks like. We're standing on the shoulders of women who came before us, that had to fight a lot harder. This is what we have to do.

Brian: We're just about out of time, Jennifer. Let me get one political analysis question in here for you, given your experience, and that is, strategically, who do you think would be the best pick for Joe Biden for his running mate?

Jennifer: Kamala Harris.

Brian: Because?

Jennifer: I think it has to be a Black woman. We can't have seen the agonies that Black Americans have been going through it, that we just saw this fight, the democratic [unintelligible 00:23:25] ticket has to have a Black woman on it, representation matters. I think, having been through quite a few of these, and having been through one with Trump, with a woman, it has got to be a woman who has been through fire. Presidential campaigns are pretty good testing grounds, and Kamala Harris proved her ability to get through that. Also, just, I happen to know Joe Biden, and I know that he really values experience in representing people, and Kamala Harris has represented a big state with lots of very diverse populations, understands what it feels like to make decisions on behalf of other people you represent, be accountable to them, and I know that he values it. Whoever it is, that woman is going to have a very tough time. Trump and Pence will come after her very hard. She will get all of the fire, more fire than Biden, and you want somebody who's tested.

Brian: Good point. When you say Black women for representation, do you mean that because it's the right thing to do, or also because it gives him or the team, the best chance of winning?

Jennifer: I mean because it was the right thing to do, but I think that Black Americans need to know that if he wants a Black woman on the ticket, he understands that that's going to make the work of their campaign and their presidency different. I think Black voters will welcome it, but moreover, you think, "Yes, you have to do that." [crosstalk] .

Brian: Jennifer Palmieri was White House communications director for President Obama. She was communications director for the 2016 Hillary Clinton campaign, and she is author of a new book She proclaims: Our Declaration of Independence From a Man's World. I can tell from the response on the phones, this, not only were you touching a cord, but it was really helpful for a lot of people to hear this. Jennifer, thanks a lot.

Jennifer: I was really glad to be here. Thank you, Brian.

Brian: Brian Lehrer on WNYC. Stay with us. [music] Brian Lehrer on WNYC, we continue now with our Labor Day special. We're airing some of our favorite work-related interviews from this summer, including this one with Dr. Anthony Fauci, who besides having a difficult job is doing it under, let's say, some challenging circumstances, and I'm not just talking about the virus. This was recorded in late June as New York entered Phase II of reopening. Anthony Fauci was born on Christmas Eve, 1940 in Brooklyn, not in Bethlehem, but he got educated in the city's Catholic school system, including the Jesuit run Regis High School in Manhattan. He says he took a bus and three subway lines to get to high school every day. He went to a Jesuit College, to Holy cross, which I think is in Western Mass. In one interview I read, he gave a lot of credit to Jesuit training in precision of thought and economy of expression, for being able to communicate science to a lay audience, as clearly as he does. For those of you from the neighborhood with very long memories, his parents owned the Fauci Pharmacy in Dyker Heights. Oh, those Faucis. He is, of course, Director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, a position he was appointed to during President Ronald Reagan's first term. He was awarded our nation's highest civilian honor, the Presidential Medal of Freedom, by President George W Bush in 2008. Coincidentally or not. Dr. Ben Carson was given the same honor by President Bush in the same ceremony. Dr. Fauci, we are so honored that you would join us today for this, to help us do a better job at reporting on health. Welcome to WNYC.

Dr. Anthony Fauci: Thank you very much. Thank you for having me.

Brian: Did I get that right, about your Jesuit training contributing to your ability to be a science communicator? If so, can you elaborate a little more on that training or those principals?

Dr. Fauci: Yes, there are two or three aspects that are very characteristic of Jesuit training. One is service to others, which is something that permeates all of their philosophy about life, is that we're really meant to be serving community and serving others. The other is that they're very rigorous with regard to truth, science, and evidence and that they feel, and have trained us who are fortunate enough to be in that training, that if you really understand something, and you're precise in your thinking, and you understand the question you're addressing, you should be able to express it with a minimum number of words. That's what they mean by precision of thought and economy of expression.

Brian: You sometimes go on cable television anyway.

Dr. Fauci: Yes. [chuckles]

Brian: When you see or hear coronavirus reporting in the major media, are there any main things you think journalists have tended to communicate well, and any main things they have tended to communicate not so well?

Dr. Fauci: I think that when they get a story, and they're interviewing, for example, a scientist like myself, I find that the media persons that I deal with, be they in radio, like in NPR, or on TV when they're talking about a specific subject, they do a really good job. They're doing their homework before the interview, and they also ask the right follow-up questions. You can tell if somebody knows what they're talking about, when you give an answer and they have a follow-up question that actually leads from what you just said, rather than the talking points they have in front of them. That's a dead giveaway. I think they do a really good job of that. The difficulty you get into when you start getting media who are clearly slanted in one political direction, versus the other political direction, and then you start getting some politization of what you're speaking about, which is not really helpful. Anybody who knows anything about what's going on today, realized that we're in a very divisive state, in our interactions with each other, that sometimes gets in the way of, either the interpretation of or the inferences that you might make out of a discussion, depending on what channel you happen to be on.

Brian: I think also, sometimes journalism gets the facts right but makes its biggest mistakes through omission; omission of scientific uncertainties, or omission of context, things like that. I'm curious if there's any coronavirus story or angle that you wish the media would do, that it hasn't done.

Dr. Fauci: I don't know if I could answer that directly, Brian, but the one thing that I find disturbing is that when you go in, in good faith, to get a somewhat difficult concept across, something that's serious, that involves the lives and health of the people of our nation and the world, and you say something in there that, not necessarily the person that's interviewing you, or the person that's writing about you, but what get clipped out of that, is a soundbite. Although soundbites I know are important to the media, sometimes the soundbite completely distracts from what the content of what you're saying is. Being on the media so much now, given the situation I find myself in, it's really very disconcerting when you said something that's important, and two or three words get pulled out, that's directed at some other question that someone wants to make a point out. Not only does it mislead, but it actually takes away from the content of the important message that was the core of what you were talking about.

Brian: Often people just want to portray was in conflict with the president, I think, and a lot gets distorted through that lens. I'm going to try to stick to the science here today overwhelmingly. I want to look back a little, look at the present a little, and look at the future a little. The general public never thought about pandemics very much, but there are experts in your field who did before the coronavirus hit. Yet, at the beginning, the CDC's initial test kit was faulty and gave unreliable results, as I understand it, through contamination or other problems. The FDA, at first, prohibited private labs from distributing their own tests as alternatives. How crucial were those two things, in your opinion, to our failure to contain the virus, like some other countries did, rather than have to mitigate it with stay-at-home orders?

Dr. Fauci: Brian, obviously, if things had gone very smoothly from the beginning, things could have been better. The ultimate extent of how much impact that had on what followed because what followed was really an enormous surge of cases that were very, very difficult to contend with, particularly in places like the metropolitan area of New York City, when you have a misstep, be that misstep and accidental contamination of tests that slowed down the distribution of valid and reproducible tests to the public health community, with which the CDC is involved in, is obviously something that could interfere with a proper response. The same thing with the idea that we ultimately got the private sector involved as is necessary and important, but we didn't do that quickly enough. I think anyone that looks at the facts has to realize that that unfortunately was the case

Brian: At the beginning of the pandemic, in the United States, it quickly became clear that the impact was disparate by race and class. A lot of that is who, in the long history of inequality in this country, has left disproportionately in the service jobs that we now call essential, and who was living in dense housing, things like that. Are there things about the healthcare system for infectious diseases, per se, that made the disparities worse, that the country could address?

Dr. Fauci: Oh, absolutely. If you look at it, there are some so very positive aspects of our health delivery and our healthcare system, but there are some things that still are difficult. That is the disparateness of accessibility to good healthcare. There were so many factors that went into the disproportionate suffering that the African-American community has had to deal with during this outbreak. Just from what you said, when you're dealing at the types of jobs that put them at a greater risk of getting infected, when they do get infected, the lack of as good access to good health care, as quickly as you possibly can, is another factor against it. Then, there's the decades and decades and decades' old, social determinants of health, which have the African-American community have a greater incidence and prevalence of the underlying conditions that make the outcome of an illness like COVID-19 much more serious in the African-American community. Things like hypertension, things like diabetes, things like obesity and lung disease, and kidney disease, all of which are disproportionate. When I look at that, I say to myself that we always get so-called smacks in the face to get us to realize things. This is shining a bright light on these disparities that have existed so long. There are things we can do about it right now, making the resources for testing, and better access to care, so that you concentrate resources in the demographic group, and the areas that have high concentrations of that demographic group right now, as the outbreak is going on. Then you make a commitment that the future, we're going to look at the kinds of things that got us into this, to begin with. If there's anything that's positive, that comes out of this, is a reassessment of what we can do about these disparities.

Brian: [clears throat] Excuse me. How much of that, in your opinion, should be in the healthcare system itself if we're trying to eliminate the kinds of structural racism outside the healthcare system that contribute to poverty? What about the healthcare system itself in terms of lessons for equity? Are you a fan of Medicare for all, or other systems for equal access? How specific can you get on any of that?

Dr. Fauci: I can't get specific on it because there are so many pros and cons, and people are arguing in a very politically charged environment now, about that. I certainly don't want to weigh in on that, but I do think when we look at our healthcare system, we have to focus on the reality of the disparities and say, "This needs to be addressed in whatever plan you ultimately decide, or whatever modification of any existing plan." It's a reality. You can't run away from it. You can't run away from it. It's there. We've got to address it.

Brian: Another major and very deadly problem area has, of course, been nursing homes. I'm curious about what you're looking for now, to know things are going better in the new hotspots that are emerging, or what you're looking for as a sign that, structurally, we're still in trouble with nursing homes, and other group facilities, as any potential second wave hits?

Dr. Fauci: There are several things there, and this is something that we've dealt with specifically, in great detail, in the coronavirus task force, mostly through the kinds of things that CMS does, since they're generally responsible for that. There are many things that could be done. For example, the infection control oversight has now gotten much, much stricter. There were many, many, many, many nursing homes throughout the country, in which there have been no infections. Just because you're a nursing home doesn't mean you're going to wind up getting an outbreak. It's how you have your staff, and the actual structure, and the standard operating procedures in nursing homes, that have made certain nursing homes highly vulnerable. You've got to fix that and fix that fast. You do that with strict regulations, where you don't wind up getting money. That's the way you've got to do that. Secondly, when you're in an area where there's a high vulnerability, you do things like test everybody there, and then surveillance testing at different intervals. That could be every week, every other week. Another thing is that you don't want an outbreak to spread from one nursing home to another. You've got to figure out a way, how to diminish people who are staff going from one nursing home to another, to another, because all you need is an infected staff. Particularly one who doesn't even know they're infected, who is an asymptomatic carrier, can wreak a lot of havoc merely by innocently go from one place to another. There's a lot of things that we can do right now, and are doing. Not what we can do, what are doing, about trying to protect the most vulnerable in the nursing homes.

Brian: Still looking back, what about PPEs? If experts knew a pandemic of this magnitude was a possibility, why were we short of PPEs when other countries weren't?

Dr. Fauci: That's a good question. I hope that that doesn't ever happen again. One of the problems that is a systemic regarding availability of just-in-time products, is that, what we have done, it's come back to bite us, is that a lot of the things that we would ultimately need in an emergency are manufactured someplace else. If you look at the fact that we had a scramble to get N95 masks, and gowns, and face shields, and other types of masks from manufacturers outside the country became very, very difficult and was quite problematic. We've got that fixed now, and hopefully, if we do get other waves, we keep talking about a second wave, we're still in the first wave, we still have a lot of problems to go through, that we don't ever even come near running out of equipment. We never ran out of, example, ventilators, but the health system came perilously close, in some places, to being overrun. The other thing that I think people should realize is that, as you mentioned, I've been doing this for a long time. My first encounter with an outbreak was in the first of six presidents that I've been in my position under, that was Ronald Reagan, during HIV. We've had pandemic preparedness plans along the way. You'd be surprised, when you're in a situation where there's no real threat, there's a potential threat, but no real threat, how difficult it is to get well-meaning people, some of whom are now complaining why we didn't do it, who, when we try to get resources to put much, much more on the stockpile, "Do you really need that much? We have other competing priorities right now." It isn't all black and white, and it isn't all good and bad. It's a lot of gray zone in there.

Brian: Another gray-zone might be that, and this might also harken back to your HIV days, you tell me, but New York is a bit of a success story now, getting the rate of infection down as low as we have. Can New York test and trace its way to actual containment now? I wonder sometimes, if obtaining the contact, tracing names, and getting exposed people to really quarantine, can actually work in our society. I think there was already an article in the New York Times about people refusing to give up their contacts.

Dr. Fauci: Brian, you have a couple of questions intertwined in there. [laughs] I'll try to unwind them, but they're good questions, all good questions. First of all, let me comment about my beloved city of my birth, New York City. On the one hand, you all got hit really badly in a way that wasn't your fault. You were the first of that wave of cases that swarmed into New York City from Europe. Everybody was looking at China, and it came in from Europe. Having suffered so greatly, I think your leadership, particularly Governor Cuomo, and Mayor de Blasio, have done a really terrific job in getting it down very, very low so that they did. I've been in many conversations with Governor Cuomo and Mayor de Blasio, who, clearly, when they got on the phone, wanted to do it right. There was no doubt that was nothing motivating them, other than the good, the health, the welfare of the citizens of New York state in general, and New York City in particular. They listened to the guidelines, to the initial gateway, to get into Phase I, and then didn't go to Phase I until they were able to, according to the guidelines. The thing I liked about that is that they listened to the guidelines, and as the governor has said when they were those pictures of people who looked like they were throwing caution to the wind, down in the East Village, said that if we don't do it right, we're not going to advance to the next phase. That was, I think, really a strong statement that other states should take a look at. Are you going to be able to do the identification, isolation, and contact tracing? I think so, I hope so. You bring up a good point, Brian. There are so many good things about the independence, and the entrepreneurship, and the lack of being told what to do with the American spirit. It's something we all cherish, but sometimes it could work against it. When people start talking about the success of South Korea, or whatever Asian country compared to what's going on here, you got to remember that we are a very, very diverse country with regard to our demanding that we make choices at the local level versus at the central level. In some respects, that's great, but in some respects, it's not good when you want to get a uniform response to something.

Brian: May I ask, when you go out in public, what kind of mask do you wear?

Dr. Fauci: I wear a-- I don't have it in my pocket because there's nobody here. Anyway, it's in my office, which is 15 feet from here. It's a cloth mask. It's a mask that's the kind of cloth that we were talking about. Remember, there was a time, back then, when there was such a shortage of masks. We didn't want to consume them because the health care workers needed them, who were able to do it. Right now I have a variety of cloth masks. My high school, Regis High School, that you mentioned, made one that said "Regis", for me, on it. I have one that says, "The Washington Nationals," on it, and I got a plain old black one that's got nothing on it.

Brian: A Brooklyn Dodger fan transfers his loyalties eventually, to the Washington Nationals?

Dr. Fauci: Yes, I'm really sorry. I had to do that, but they are a great team.

Brian: You say cloth mask, I'm curious if you have an opinion about mask design for the general public. Of course, people who don't have N95s-- There was a university of Chicago study, maybe you saw it, that concluded a homemade or commercial mask, could approach N95 protection if there's a layer of 600 thread count cotton meshed with a layer of chiffon or silk because one filters the smaller droplets pretty well, and the other filters, the bigger ones, and then a snug fit to prevent air openings, and that it also provide coverage back toward the ears, people say. I'm just curious how much you think mask quality is an issue we should talk about more, or whether it's a distraction that would make the perfect, the enemy of the good, and not enough people wear masks at all?

Dr. Fauci: A little of each, Brian. Let me explain why. The first thing you got to remember is, before you get bent out of shape about the quality of the mask or not, a mask is better than no mask. That's getting to the perfect being the enemy of the good. Put a mask on, you've got a cloth mask, what you embed it with, I would hope, given the entrepreneurial nature of our country, that there's a lot of groups that are figuring out how to make a mask that they'll be able to advertise is X% better than any other mask. That's great, go for it. I hope we do it, but the most important thing you want to concentrate on, put a covering in front of your face, and then we'll worry about how good it is a little bit later

Brian: Question from one of my WNYC colleagues. If the world was able to completely shut down, and people stayed home for two weeks, the period of time where people would recover or die from the virus, could COVID-19 be eradicated?

Dr. Fauci: Yes. Theoretically, yes, but it's such an impossibility. It's such a transmissible virus. All you need is a few in our world of, how many, 7 billion people, it won't happen. In a theoretical standpoint, I think the point you were making Brian, which is true, is that the viruses need to have interaction between people to spread. If you were to theoretically, which is impossible to do, but if you were able to do that for the time it takes for all incubation periods, you could theoretically do that, is to shut down every interaction. Remember, it jumped species from an animal to a human, so you might do it now, so rather than thinking-- Not rather than, but in addition to thinking about that, we should be thinking about addressing those things that tend to promote or make easier, the jumping of these types of viruses from animals to humans. The first thing we need to really concentrate on now and when this is over, is, what the world's response should be to these wet markets where very exotic animals come into contact with people because we've had 3 coronavirus outbreaks since 2002, that were direct results of the interaction of animals in wet markets. Not necessarily wet markets, but bats to civet cats, which is a wet market animal. Bats to camels, not a wet market, but an animal. Now, bats to an intermediate host, to us. We've got to cut out that interaction. If you're just joining us, we're re-airing parts of our late June interview with Dr. Anthony Fauci. I asked him, at one point, about states with surging outbreaks, but with governors who didn't want to shut back down. This is still going on here on Labor Day. I asked Dr. Fauci what he sees as the best practices.

Dr. Fauci: In general, when you have an outbreak of a period that we're seeing in any of a number of places, any number of states, the best way to interfere and mitigate that is to discontinue, or pull back on the interaction with people. You don't have to lock down completely, but you may want to pull back a little. The other thing you need to do is to implement with the right manpower, the right testing, the right systems, to identify, isolate and contact trace to the best you can, to be able to get your arms around that. That's the thing they need to do. It's unfortunate that there are now, in multiple states, outbreaks. That was predictable. I had said it many times publicly, and I'll say it now; when you are in a situation where there is a degree of viral dynamics in your community, and you know that, and you take a leapfrogging jump over the carefully thought out benchmarks and checkpoints, you increase the risk of transmissibility, and acquisition. It doesn't mean it's going to happen every time. There are some situations where they have gone in a rapid way, and there haven't been outbreaks, so it isn't inevitable, but the risk becomes much higher when you do that. You can talk about any state or any location you want. When you disregard the checkpoints if you're in an area with activity-- Now, so that people don't misinterpret it, there are some areas right now, counties in the country, there's very little activity. Go for it, go do your thing, go to the next step, and the next step. When you're sitting in the middle of a place where there's activity like that, you've got to be very careful because you increase the risk.

Brian: Last thing, and then I know you got to go. Are you concerned about people being fearful of a vaccine that feels rushed? This is the intersection of science and politics coming up again, questions submitted by a WNYC colleague, and therefore not choosing to take it? How do you avoid that?

Dr. Fauci: I'll go one step upstream and say, I'm concerned about an anti-vax feeling in parts of this country that are disturbing because, in general, they are forgetting COVID-I9. They're based a lot on misinformation about a proposed adverse events that never occur. The famous autism and measles, mumps rubella vaccine. There is a feeling, in some areas, of anti-science, anti-vax. That, I think, is going to influence how people look at the vaccine situation with COVID-I9, particularly since it's being done in an accelerated way. I want to assure people that the acceleration is not at the expense of the safety considerations by any means, nor is it at the expense of the scientific integrity. You want to move as quickly as you possibly can. The only thing you put at risk is not people and safety, is, you put at risk, money. In other words, you're going more quickly than usual because you're making investments in things that you don't even know are going to work yet. If they don't work, then they don't work, all you've lost is a lot of money. If it does work, you've picked up several months in the process of developing it. I think what we need is community outreach. We can't assume that, in this era of mistrust of authority, and in many respects of mistrust of science, that people are going to take on face value what you say and believe you. You've got to go out and reach out to the community. You've got to get public service announcements to explain, and be transparent about what you're doing. Hopefully, when we do that, we'll be in a situation where people will get vaccinated if we get a successful vaccine. We won't let a vaccine out, at least I won't be a part of it unless it is safe and effective.

Brian: I don't know if you're being pulled right onto television at this moment or something, but if I could extend for one follow up question, we did a segment on my show about you and the ACT UP organizer Larry Kramer, who, of course, died recently, and ACT UP's push back in the '80s and '90s, on the need to get AIDS drugs approved more quickly. You've spoken openly about how you learn from Larry and ACT UP. Is that experience informing your approach to COVID-I9 treatment or vaccine development at all?

Dr. Fauci: Yes, of course, Larry and I go back over 30 years. I'm so sad that we lost him. I learned a lot not only from Larry but from the activists, what he used to call his children, who he trained, who are now very, very experienced individuals who know a lot about the interaction between government and the community. We learned that you've got to involve the community. You cannot do things in a dictatorial fashion, and in a way where you think you know it all. You've got to be transparent, and you've got to involve them. In fact, some of the older ACT UP people from back in the day, as they say, are working with me right now, and helping us to be able to extend ourselves in a transparent way to the community. We value their input. A lot of lessons were learned back then, Brian.

Brian: Dr. Fauci, thanks so much for your time, consulting with us today. Our reporting will be better for it. I'm a great admirer and good luck helping to steer the country through the next phases of the pandemic.

Dr. Fauci: Yes, thank you, and thank you for having me.

Brian: Anthony Fauci, recorded in June. [music] It's The Brian Lehrer Show on WNYC. Good morning again, everyone. With us now, is emergency room physician, Michele Harper, who has a new memoir called The Beauty in Breaking. Dr. Harper has been chief resident in Lincoln hospital in the Bronx, served at the Veterans Affairs Medical Center in Philadelphia, and more. Besides her book, Dr. Harper wrote an article on Medium, about the stress of constant intubations and PPE shortages during the coronavirus pandemic. That article is called When This War Is Over, Many of Us Will Leave Medicine. Dr. Harper, thank you for your writing and your time today. Welcome to WNYC.

Dr. Michele Harper: Thank you. Thank you for having me.

Brian: Can I ask you right off the bat about the title of your book, The Beauty in Breaking? How do you mean breaking in that title?

Dr. Harper: I referenced in there, in the beginning, a Japanese art form. If I mispronounce the name, I apologize, but, kintsukuroi. In that practice, when a piece of pottery or art is broken, that pottery is repaired by an amalgam of precious metals. The breaks are actually highlighted. The thinking is that it's more beautiful after the mending. I mean that in the same way with human beings. I never romanticize trauma, but that we're all going to have difficulties in life. This is just part of the deal, but in the process of healing, we can become more resilient, stronger, and we can go on to help other people. For me, that is beautiful.

Brian: Is that both about yourself, as well as the patients you see in the emergency room?

Dr. Harper: Definitely. It's where the book demonstrates our interconnectedness in that way.

Brian: You describe, in the book, for example, the time you went to the emergency room with your brother, as a teenager, and first got the idea that you might want to work in a place like that, for your profession. It was also a very intense moment, I'll alert the listeners, in the life of your family. Can you tell our listeners some of that difficult story because it seems pivotal to your decisions about your life?

Dr. Harper: That was one story. I grew up in an abusive home with a batterer for a father. There was always violence. If not actual violence, then the threat of violence. I speak about one incident where my brother, in an effort to protect my mother, began to fight with my father. He had him pinned to the ground at one point, and my father bit my brother's hand. For me, it was a deep bite, and it stuck with me. I was young at the time, and I thought to myself, because I didn't have the words, but I had the feeling that this is a person I'm related to. This is supposed to be my father, and my brother's father also. If he's capable of such a brutal act like willing to maim someone, what does that mean? We are not safe and anything is possible. That is an incident like many that stuck with me that formed me and that had me feel that there wasn't safety in my home and that I wanted to be part of a structure to help other people moving forward.

Brian: Because that time in the emergency room in that part of the story, you saw a sense of order, a sense of service. Am I putting the right words on it?

Dr. Harper: Yes, I think so. [chuckles] Order in a very chaotic place. Where people from all walks of life, like children brought in by a parental figure, older people brought in by ambulances unconscious in cardiac arrest, homeless people who are just trying to get some respite from the elements. Everyone comes here seeking something, seeking some way of feeling better, getting better, and I can relate to that. It appealed to me that that might be possible somewhere.

Brian: Also, in that part of the book about your growing up, you describe an earlier family fight when you were a tween, I think, and called 911. The police came and couldn't figure out whether to arrest your father or your brother, and wound up leaving without making sure you and your mother were okay, you describe it as. It seems so relevant, now that the city and the country are discussing whether the police are the right people to respond to domestic disputes, even ones involving violence. I'm curious; of having lived through what you did as a child and now with an ER doctor's experience, do you have an opinion about what kinds of reform in that area are needed?

Dr. Harper: Oh, my gosh. We need many reforms. [sigh] First of all, in that situation with the police, for example, they just need systemic change. It wasn't difficult to figure out the dynamic there. Could they have been helpful? Yes, but that just depends on their level of insight and their intentions. In terms of violence against women; I mean, where to begin? That has to do with how we're socialized in our society with treating people with dignity and respect. Addressing the pay wage gap, addressing-- We could go on. [chuckles] This is going to take reform on multiple levels in society's structural change.

Brian: Sure. I guess I'm curious with your perspective through that story and working in the ER where you have contact with people who were brought in by the police, et cetera, whether you have a particular take on police reform. Whether there's a way, as we debate in New York and elsewhere, as you know, defunding parts of the NYPD and other police forces and moving those functions, with respect to domestic violence is the example that I'm thinking of, into other agencies. I'm just curious if you have an opinion whether that's doable.

Dr. Harper: I do believe it's doable. I'm sure that it would need policy experts on and people who are experts in finances, but yes I do. Having worked in- well, mainly I always work in inner-city environments and having to collaborate with, for example, Child Protective Services that are undefined and don't have enough staff who need help in order to follow up with families and provide them with resources; yes, there are organizations that could use the funds where police work wouldn't be relevant, but they're often called to fill in the gaps.

Brian: When you were on Weekend Edition with Scott Simon recently, I know you described a situation you write about in your book, in which the police brought in a man in handcuffs, under arrest, to the emergency room and the police said he had swallowed drugs, I guess to hide them is the implication, and they wanted you to get them out of his body against his will. Could you describe that incident again for us, and why racial justice became a factor in your decision about what to do?

Dr. Harper: Yes. Well, as you said, a man brought in in police custody. Yes, swallowing drugs to hide them was the allegation. Clinically, and this is important, the patient was fine. He was not clinically intoxicated, there was no signs of altered mental status, nothing. The patient didn't want any evaluation or treatment of any kind, although it wasn't clear he needed any treatment. Any patient who comes into the ER has that right as long as they're competent medically, and he was but the police wanted it done anyway. Staff in the hospital told me that they often; if that's what the police want, they just do what they want and the rights of the patient are disregarded in those contexts. What shocked me was that in the department at that time, the patient and I were the two darkest people. I was the only Black doctor, and in terms of the police and the nurses and my resident who I was training, they were all white at that time. Then the [beep] [inaudible 01:06:10] called the hospital. I was going to discharge him. The resident called administration in the hospital, the medical legal department, to see if she could override my decision even though I'm the attending. I'm the doctor in charge. They alerted her that actually she can't because I'm right, and as I had told her and the police, it would be illegal. Not only unprofessional and unethical, but illegal to force an exam on this patient. It would be assault. So, he was discharged. The reason it was relevant is because not only was it that the patient was presumed to have no personal sovereignty, no bodily integrity- it didn't matter what he wanted, we were supposed to override that- but the medical institution was complicit in that. My resident felt that I didn't have the authority either to make that decision. That story highlights many things, and one of them is racial injustice.

Brian: Yes. You write in the book in various ways about being an African American woman in a job typically filled by white men, emergency room physician, and that story is one example of your background informing your work. Not to overgeneralize in this question, but do you think some of the white men in the field have certain blind spots that are common, which would be some of the reasons for the need to diversify the profession?

Dr. Harper: Yes. [chuckles] I can answer that quickly; yes. [laughter]

Dr. Harper: Yes, 100% [crosstalk] --

Brian: Good. Now, you have to give me examples. Go ahead.

Dr. Harper: [laughs] [unintelligible 01:08:02] . I talk about in a lot of different ways and actually an interview that answers this in more depth just came out in people.com yesterday. For example, I was going for a hospital position. It's not uncommon. We work clinically in the ER as emergency medicine physicians, so often get involved in administration as well. I was going for a position in the hospital and I was the only applicant, but I found out that they decided they weren't going to hire me for it. My boss, the emergency room director, called me in and said, "I'm so sorry. You were the only applicant and you were super qualified, but they decided just to leave it open." Then he told me that he's never able to get women or people have color promoted in the hospital. They just won't ever do it. That's why they always leave, and he hopes that I will stay on with him anyway because maybe one day it'll be different. I did end up leaving and I found out from colleagues, not long after, that they hired a white male nurse for the position. That's just one example [crosstalk] --

Brian: A nurse not even a doctor.

Dr. Harper: No.

Brian: That's a tough one because your supervisor there was-- I mean, it's an infuriating one. Your supervisor there was choosing to enable the racism of the higher-ups rather than confront it.

Dr. Harper: Yes, and that happens all the time. His effort, if I can call it that, to hire; he did hire women and people of color. That's true, but when it came down to really fighting for justice in that way within the system, it only went that far. Which is not far enough.

Brain: My guest, if you're just joining us, is Emergency Room Physician, Dr. Michele Harper, who has a new memoir called The Beauty in Breaking. We'll continue in a minute with Dr. Harper. Stay with us. [music]

Brian: Brian Lehrer on WNYC with Emergency Room Physician, Michele Harper, who has a new memoir called The Beauty in Breaking, and we will also get to her article on Medium called When This War Is Over, Many of Us Will Leave Medicine; the war being the war against Coronavirus. I lost track, having read so much about your history in the book and your bio. You just said you're practicing currently in New Jersey. Where do you work?

Dr. Harper: I don't say where I work.

Brain: You don't have to.

Dr. Harper: Yes, but it's in New Jersey.

Brain: Got you. Local girl. Jennifer in Manhattan, you're on WNYC with Dr. Harper. Hello, Jennifer.

Jennifer: Yes. Good morning, and thank you for taking my call. Dr. Harper, I'm struck by the fact that you grew up obviously in acute dysfunction and violence, and not only did you choose to become a healer or a physician, but you chose to focus in emergency medicine; i.e., working with people in crisis. Have you addressed the fact through this extraordinary mechanism of reaction formation that you took such a painful and difficult task and channeled it in an extraordinarily positive and productive way?

Dr. Harper: It can go either way. People, I feel and what I've seen, is they can either learn and heal from that trauma and then go on to do positive work, or reenact it and recreate those cycles of violence in their own life. Certainly, my father had a lot of loss in his background; not having a father figure and losing his mother early. Yes, that would be an example where he didn't heal from it, he recreated the trauma. That's common, but it was important to me to not do that. So, I did a lot of work on myself so that I would heal and break the cycle.

Brain: Jennifer, thank you. Steve in Queens, you're on WNYC with Dr. Michele Harper. Hi, Steve.

Steve: Thank you very much for taking my call, and good morning to you both. I wanted to say to her, thank you very much for what you're doing and for what you tried to do at that hospital. As I explained to the screener, I said it happened in '87, but the feelings are still there; hatred, anger. I was in Central Park to meet up with some friends, and I walked over to two cops in a van to ask for directions. Anyway, all of a sudden, it's, "Put your hands on--" Whatever. They called back up when I didn't do it and they attacked me. I was then taken to Metropolitan Hospital, for which there was a nurse who had a working relationship with them, and she immediately became a cop. She started cursing me like them, she was carrying on. When I told her I'm not a criminal and don't care to be treated this way, she shot me full of Haldol and Benadryl, and left me there burning up in 90-something degree weather in that hospital. When they called my mother to come down there- she's gone now- but they called my mother to come down there. When they found out- I later found this out after I sued them- when they found out that I was not on parole, I had no criminal record; when my mother showed up, every last one of them were gone, including the nurse. Everyone was gone. They were out of that room. You know what I'm saying? The feeling was that- what I later found out was they were looking for a person in Central Park with a gun and I was acting cool. For which I asked the cop, this was sometime later, "I heard Sammy Davis and Miles were in New York at the same time. Did you also grab them too?"

Brain: Steve, I hear your story. Dr. Harper, without knowing all the details or other people's sides of that story, I'll bet that has echoes of things you run into as an emergency room physician in the city [crosstalk] --

Dr. Harper: Oh, yes, it does and it is disgusting. Thank you for sharing that. It's horrific to hear. That's why I bring up the fact that-- We do have, typically, most ERs, and I trained in New York City and I could certainly say when I was at Lincoln and there was a police precinct there- at least at the time- we had a close working relationship with the police. The police and the hospital. It was actually really positive, nine times out of 10, but then there were other times when it wasn't. But it's our job, as medical professionals, to not be complicit. That's our job. I don't care if it's the police bringing someone in, their family member; it is our job to stand up for the welfare of the patient and the larger community and justice. A failure to do so is a failure of this system. Part of the reason why I tell that story about Dominic is that it's an example of where the police were wrong and the medical institution is wrong, and both need to be addressed. Because the story you tell, sadly, is far too common and it can't be ignored. The story must be amplified and corrected.

Brain: Steve, thank you for sharing it with us.

Steve: Thank you.

Brain: We have a few minutes left. Your article on Medium was back in April; When This War Is Over, Many of Us Will Leave Medicine. It's a compelling but difficult read for the illness of the nursing home patient you describe, and your own uncertainty about whether your PPEs were sufficiently protecting you and your colleagues. Do you think that the scene you describe of having to reuse your contaminated N95 has been resolved as an issue in this country, at least that, by now?

Dr. Harper: No, definitely not. If anything, it's worse. There are still shortages. We've had donations, which are helpful. Donations from companies, so we have a nice share of face shield now. They're on limited supply, so we guard them and keep them very safe. It's one. Like I have one face shield. That's the one I've been using. In terms of the N95, they've developed a recycling program. This isn't a new standard, though. We would never be allowed to reuse our masks. They would never be recycled before, but now they're sent out. There's some treatment. We're not refitted for them. We don't know if they still fit properly and this is just how it is. There are fewer cases, at this time, we think. I say we think because we still can't test everyone because we don't have enough tests, but even with this stopgap measure, we don't know what will happen in the fall, for example, if that's when the spike is. We don't know if it's going to happen before. But we don't know, our resources are already strained, to what will happen when they're even more cases. So, no, it's not better.

Brain: Have you followed the issue? Since your article revolved so much around the story of a nursing home patient who was brought to the hospital who you were treating, many nursing home guests in New York State after the transfer of COVID patients back to their nursing homes when they were then well enough for that in order to clear the hospital beds, which was very important, but with the risk of bringing contagious people back into those nursing homes; do you think there was an alternative to those awful choices?

Dr. Harper: Now, in terms of discharging people from the hospital who were safe to discharge, there was no alternative to that. There just wasn't because we didn't-- At the height of it, we lacked the space to take care of people.

Brain: Yes, you needed the beds [crosstalk] --

Dr. Harper: That there was no alternative to. On a community level, I don't know exactly what the solution are. I don't know what the resources; if there could have been hotels rented or vacated and used for that reason to space people out. I will tell you another population where it was just awful seeing the extent of disease, the severity of the disease, and the treatment of people, is in prisons. That was another population. That was heartbreaking for me to see what was happening there, and how young healthy people were being just devastated by this illness and that didn't have to be the case. Whoever doesn't-- And that's a larger discussion on the carceral state, but certainly whoever doesn't need to be in prison, which is many people, nonviolent offenders, they should have been released. We could have prevented disease and mortality there.

Brian: Why do you say, to the title of your article, that after this war against COVID, many of you will leave medicine? Why wouldn't it be a horrible war finally over when that day comes and things can go back to the hard-enough old normal?

Dr. Harper: [chuckles] Well, this is in a larger context of the business of medicine becoming increasingly demoralizing to providers, where there's less time to to actually take care of patients. In America, unfortunately, the focus is on billing and profit-making for whatever institution or group you work for, and it's less about wellness and health. There was already this movement towards people leaving medicine. Now, we have this crisis and during this crisis, we were treated as more disposable than our equipment. That just exacerbates the feeling, and I do you think more people will leave. Am I ready to leave medicine? My personal mission with medicine isn't done, but I'm seeing the effects on my colleagues and it's becoming less tenable.

Brian: I hear you. Last question; what's the career path, typically, of an ER doctor? Is it to do that for your whole career, or do that for a while and then set up more of a practice where you have ongoing relationships with patients? Which might be satisfying for someone like you who seems so relationship-oriented, but also just out of the constant trauma of seeing people at the worst moments of their lives.

Dr. Harper: That is a good question. Emergency medicine, that is a specialty. There are some people who are hospitalist doctors, and what they do is they just cover the hospital [unintelligible 01:22:39] . ER is the same. Our specialty is literally to work in the ER. That's the job. Now, do some of us go on to work in urgent care, for example, just because it's less stressful? Yes. You don't get relationships there. You just have a better schedule and less security, but that's it. Some people set up like Botox centers, but for the most part, ER is to work in the ER.

Brian: ER, or Botox center or- [chuckles] [crosstalk] --

Dr. Harper: [chuckles] I know. Isn't that terrible? [chuckles]

Brian: -or something in between. Michele Harper has written a memoir called The Beauty in Breaking. Thank you so much for your work. Thank you so much for a wonderful conversation, doctor.

Dr. Harper: Thank you. It was wonderful being here.

Brian: Brian Lehrer on WNYC. More to come. [music]

Brian: It’s the Brian Lehrer Show on WNYC. Good morning again, everyone. At the start of the pandemic, grocery store workers and other essential workers in the service industries were hailed as heroes on social media, sometimes given thanks in-person in ways they weren't before. Mayor de Blasio talked about a ticker tape parade, and occasionally, people even offered hazard pay that wasn't available before. But now as the Coronavirus crisis continues and people are antsy to return to normal, some retail workers on the frontline say that the gratitude and the extra money have mostly dried up, but the work, of course, is still as draining and risky. With us now, and to help invite calls from people who do work in the service industries, is Abha Bhattarai, reporter covering the retail industry for The Washington Post. Her latest piece, it's all about this, it's called Grocery workers say morale is at an all-time low: ‘They don’t even treat us like humans anymore.’ Abha, thanks for doing this with us. Welcome to WNYC.

Abha Bhattarai: Thanks so much for having me.

Brian: That quote, they don't even treat us like humans anymore, comes from one of the people you interviewed, right?

Abha: It does. I spoke to dozens of workers around the country and the overarching theme was, like you said, at the beginning of the pandemic they were hailed as heroes. They felt a real sense of purpose and pride. They were scared about going to work, but they still felt like they had a meaningful role to play, and now they say all of that has gone away. The customers are not treating them as well; corporations, they're not treating them as well. They're feeling more desperate, but at the same time, there are no other job options out there.

Brian: To get right into what might matter the most to a lot of people; hazard pay. You write, "Most retailers have done away with hazard pay even as workers remain vulnerable to infection, or worse." How prevalent has the advent of hazard pay been over the past months and when did it start to trickle off?

Abha: Back in March and April is when we saw a lot of major companies, almost all of the major teams were offering $2 or $3 extra an hour. Some of them are giving lump sum bonuses instead, but all of that went away in a matter of months. A lot of workers say now that at the time, they were hopeful. They thought maybe this was going to be a long-term tipping point, that they would finally be treated as essential workers, be paid a living wage, but they didn't expect it to go away so quickly. Now that that hazard pay is gone, they say there's really no hope that they're going to see it again or that conditions are going to improve in any meaningful way.

Brian: How much was hazard pay, if there's a numerical answer to that question? Obviously, it's going to be different in different companies, but what was the general range? What did people get for being retail workers in grocery stores and other places where they generally get very low pay but had to come to work before they could even really figure out how to control the risk?

Abha: The general hazard pay was about $2 an hour extra on top of what they were making.

Brian: $2 an hour. Not much to begin with.

Abha: No, it's not.

Brian: In fact, you reported last week that profits soared by about 80% at both Walmart and Target during the second quarter driven by a surge in online orders. I guess that's different-- Well, I don’t know. It's not just the people in the retail stores meeting customers, but the risk also pertained to people working in the warehouses going out, making deliveries, going into who knows what kind of building, all that stuff, right?

Abha: Absolutely, and a lot of warehouse workers say the same thing. They're working in really cramped quarters. It's difficult to be socially distant. They might not be dealing as much with the public and with shoppers that are coming in, but they're still working under very strenuous conditions. We are hearing reports of COVID cases spreading throughout warehouses.

Brian: Anybody for whom this sounds like you, we're inviting you to call in as we continue to cover on this Show and give voice to essential workers of various kinds during the pandemic. Do you work in retail as a “essential worker” maybe at a store that's been open since the start of the pandemic? How is your morale now, maybe if you're in the delivery portion of things, versus the start of the pandemic? Did you receive hazard pay at one point? Are you still receiving it? If not, what reason or excuse did your employer use for pulling it away? Are you doing work that's outside of your job description, like asking customers to wear masks and sanitize and re-sanitize, calming anxious customers, not being compensated for that extra work now that you're psychologists and social workers too? Are you noticing a shift in how customers treat you? Are people patient, grateful? Has that become less so over these months of the pandemic? With Abha Bhattarai who covers the retail industry for The Washington Post. I bet that it's been different for you, too. You cover the retail industry, suddenly you're covering life and death.

Abha: Absolutely. Yes, I'm used to covering major companies and retailers, and it's really become a story about workers, and I think those are the important stories to be telling right now.

Brian: What kinds of stories were you hearing with respect to respect, [chuckles] to put it plainly? How are customers treating the workers you interviewed?

Abha: At the beginning of the pandemic, many of them said customers were stopping them to say thank you. Some of them were bringing them cookies or other snacks, bringing them food just to show appreciation. They were really going out of their way to make sure they felt appreciated, but in the last few months, I think everybody is just kind of over it. This pandemic is going on for far longer than I think a lot of people had thought it would. There's no end in sight. Now, customers are impatient. They're angry if the store shelves are empty. They don't want to be told to stay six feet apart from other shoppers. They don't want to be told to wear a mask in some cases. So the stakes are much higher for the workers. They feel like they're at risk of getting COVID, but also of angering customers and maybe being on the other side of that. It's just a very fraught position that they've been put into.

Brian: Let's take a phone call. Alison in North Salem, New York in upper Westchester. Alison, you are in WNYC. Hi.

Alison: Wow, this is amazing. Hi, Brian.

Brian: It's amazing for me. Glad you're on.

Alison: Yes. I am calling-- I pulled over. I work later today at two o'clock. I work for Starbucks. I'm just calling because I very much agree with the sentiment that's being discussed right now. One of the disappointments I want to express is not only in the clientele, who's visiting and really not treating us like heroes as maybe we were at the beginning, the business I work for also has promotions on a freeze. We've trained people to start as new hires who have quit in the middle of their training because there's very little that is appealing about doing this work. The people who are sticking it out, instead of getting bonuses for office furniture or being told work from home until next year, we're showing up for work every day and not being told that there's more for us to gain by doing our very best; working hard, being kind to people trying to make their day, offering a bit of normalcy. I feel like a social worker right now. I feel like my job is to create an experience where visitors have something that feels like normal life, and we get no acknowledgement for that.

Brian: The social worker serving your coffee at Starbucks.

Alison: Correct.

Brian: Did you say you got hazard pay at the beginning and they pulled it back?