Day-After-Thanksgiving Dive into History

( carfull...assignment: Mongolia / Flickr )

[music]

Brian: It's the Brian Lehrer Show on WNYC. Good morning, everyone, and happy day after Thanksgiving. I hope you got to strike a good balance yesterday, between safety and celebration, and that even in this year of so many challenges, that you could find the path to gratitude. I hope you at least have one of the good things about Thanksgiving today, leftovers. Now, this has been a year like no other in history, obviously but that has also made us think about our place in history.

The Racial Justice Movement exists in the context of 400 years. Can we fix today what we don't understand from yesterday? The pandemic puts a spotlight on a long history of battle against diseases, and of believing hoaxes over science. The election forces us to confront not just the candidates this time around, but the frailty of democracy itself, and the lore for some of authoritarianism. For this day, after Thanksgiving, we're going to dip into our collection of conversations with historians.

We'll go all the way back to a 2003 conversation on the show with the late oral historian Studs Terkel, who helps us put our family histories in the context of a national one. We've got Kevin Young on the history of yes, the hoax in American culture. We've got Ron Chernow talking about Ulysses S. Grant in 2017. The issues around reconstruction made newly relevant by that year's violence in Charlottesville. We've even got a history of a love song on today's show.

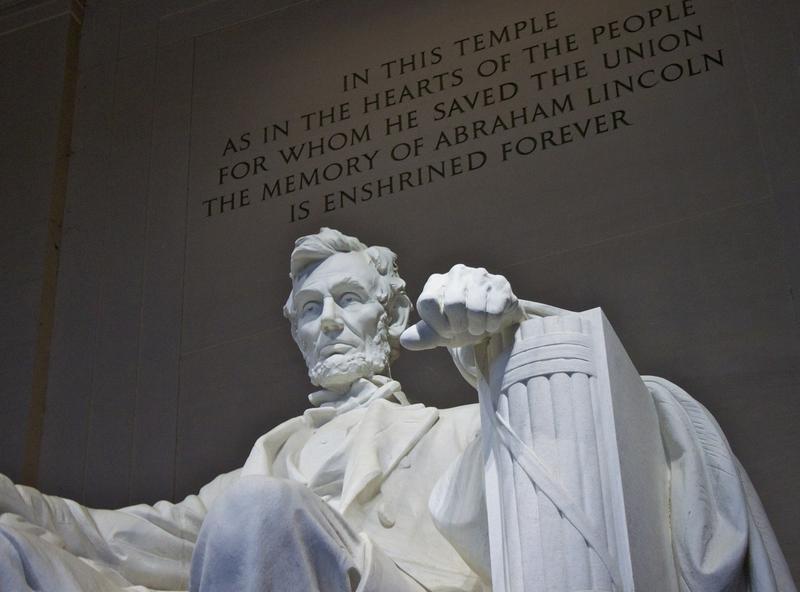

We begin with Doris Kearns Goodwin. As Joe Biden decides who will be in his cabinet, it's a good day to revisit Doris's classic book Team of Rivals about how Abraham Lincoln chose his. This conversation with Doris Kearns Goodwin originally aired in 2005 and it happened to be on the day after Rosa Parks died so we'll talk about her place in history too. Now According to USA Today, there are more books in print about Abraham Lincoln than any other US President, 1,191.

George Washington is a slacker by comparison in second place with 805 books in print about him. Then Jefferson JFK and believe it or not, Bill Clinton. It's a good thing historian Doris Kearns Goodwin has come up with a fresh angle on Lincoln and she really has the book is called Team of Rivals. It places Lincoln in the context of three of his competitors for the Republican presidential nomination in 1860, William Seward, Salmon Chase, and Edward Bates.

After the election, Lincoln appointed them all to his cabinet so we'll talk about Lincoln the man and the politician. Even the little piece that's made some of the more erudite gossip pages about how Goodwin finds a certain Lincoln picture sexy, and how Liam Neeson will play Lincoln in a movie adaptation of this book. Doris, it's great to have you here today. Welcome to WNYC.

Doris: Oh, thank you. I'm delighted to be here.

Brian: Published by Simon & Schuster as you mention, why this framing of Lincoln in the context of rivals?

Doris: I think part of it was when I first started, I knew how many books have been written about him, and I wanted to be able to have some angle that would be my own. When I was working on Franklin and Eleanor Roosevelt, I fell in love with the idea that there were a whole series of colleagues that surrounded him who were fascinating, Harry Hopkins, Lorena Hickok, Winston Churchill coming and spending weeks at a time in the White House across from Roosevelt.

I found these people, and they all larger than life, they all kept diaries, they all wrote letters, unlike Lincoln. Personal letters about their affairs, about their sadnesses, their treachery, their jealousies, so I could get inside Lincoln through my characters, my guys, as I began to call them.

Brian: Your book has been praised already for a [unintelligible 00:03:51] and today's the actual release date, right?

Doris: Correct.

Brian: For illuminating something about the nature of male relationships in the mid 19th century, was that one of your goals?

Doris: I don't know that I thought about it that way. I mean, obviously, one of the questions that get asked recently was was Lincoln gay? As I looked into the other male relationships of all my guys, it was clear that there was something in common that was similar for Lincoln as well. For example, one of the reasons people think Lincoln might have been gay is because he slept in the same bed with his great friend Joshua Speed for three years.

I discovered by looking at all these other people, it was incredibly common to do that. We didn't have the same sense of privacy then that we have now. At the same time, he wrote affectionate letters to his friend Joshua Speed, but all of my guys did. Men were able it seemed to me to express their love to one another. Stanton and Chase who both became Secretary of War and Secretary of Treasury under Lincoln had a friendship in their 30s.

They'd both lost their wives and so the intensity of their relationship was making up for those losses but Stanton writes to Chase saying, "Ever since our pleasant intercourse last summer, no one in my life matters more than you. I dream of you. I can't wait to hold you by the hand." No one suggested they were gay. It was just that I think men felt freer then than they might now to express their feelings, so that's the context in which I would put this male relationship thing.

Brian: It's funny, this is off the topic of Lincoln, but somebody a few years ago published, side by side, all the photos of I think it was the Yale football team, from the time photography started at that popular level very early in the 20th century. In the early photos, the guys were all over each other. They were just flauting all over each other and eventually, they were standing stoically side by side so I guess something really changed in the culture.

Doris: I think one of the things that changed in the 19th century when women had to be chaperone to be with men, it was hard to have friendships among single men and single women so women, women became very intense with each other and men, men, did. You see photos of women with their arms all wrapped around each other in the 19th century, same as the men. I think in some ways, it was just a need for that friendship, which was a great thing.

Brian: What did you learn about the nature of these rivalries on a human, not just a political level?

Doris: The interesting thing was to watch the arc of some of these relationships. For example, Seward, who became the Secretary of State, but had been the governor and senator from New York. He was much larger than Lincoln. There were 10,000 people waiting at his home in Auburn, New York, the day of the Republican convention in 1860, certain that he would be the nominee. They'd already uncorked the champagne and he thought he would then once he was put into the cabinet control Lincoln because Lincoln would be just a figurehead.

He eventually comes around to understanding Lincoln's mastery, and become so close to him that they become great friends. Stanton, who had been a lawyer in the 1850s and had humiliated Lincoln. He was a nationally known lawyer but had humiliated Lincoln in a law case, didn't want to read his brief, looked at him, thought he looked disheveled, decided that he couldn't help the case. Lincoln left that law case feeling it was one of the worst experiences in his life.

Yet he appoints him as Secretary of War, and Stanton ends up loving Lincoln more than anyone outside his family. On a personal level, what was so interesting to watch was how these rivals, eventually some of them turn toward an understanding and a love for Lincoln. Chase, the Secretary of Treasury never did. He tried to run against Lincoln in 1864 but then, amazingly, Lincoln appoints him Chief Justice of the Supreme Court, even after that treachery, knowing he'll be the best man for the Black man.

Brian: Talk to me a little bit about one or the other of Salmon Chase and Edward Bates. People have at least heard a little bit about Seward because they know of Alaska and Seward's Folly. Were these other guys interesting?

Doris: Salmon Chase was fascinating, partly because his ambition was never satisfied. He's so wanted to be President of the United States that even though he was Secretary of the Treasury, Governor, Senator, and eventually Supreme Court Chief Justice, it was like a missing link in his heart. I think partly that ambition came from a very sad, private life. His first wife died in childbirth at 25, his second wife died in her 30s, the next one died at 32.

How you absorb that it's hard to know but he had a daughter, the most beautiful girl of her age in Washington during the Civil War, who became his surrogate wife. She was so ambitious for her father, that she married a very wealthy older man Sprig so that the million dollars could help her father's political career and ended up sadly.

She could have had any suitor she wanted. He turned out to be a very difficult husband, abused her, and she ended up in poverty so that circle tube was so interesting to me. When you get into these people's diaries and letters, and you understand what their private lives are like, it just I think, enforces the public side as well.

Brian: How did Lincoln win that presidential nomination if he wasn't expected to?

Doris: I think partly it happened, he was lucky that it was in Chicago, his home, not his particular home, but he stayed home. They were able to pack the hall with Lincoln supporters, partly because he had not made enemies all along the way which each of his rivals had done. Everybody who had met Lincoln stayed a friend. In fact, people that had heard him earlier had become friends, partly that he worked harder on it than any of the other ones did.

Some of them took it for granted. Also, because the speeches he had given in the 1850s were so filled with a moral quality, that people knew that if they couldn't have Seward, the most radical of them all, Lincoln would be the best to protect anti-slavery. A lot of things came together.

Brian: There was no TV, there were no photographs so did a candidate run in national elections by having people read his speeches?

Doris: Exactly. The speeches would be-- Well, first of all, people would come. I mean, 10,000 people would come to the debates. For example, in 1858, when he was running for senate against Stephen Douglas 10,000 people would come from all over to listen to him speak for four hours. I mean, it's inconceivable today but they'd picnic that was there. It was the sport. It would be like baseball or sports today. Politics was the spectator sport and a participant sport.

I mean, they'd be screaming from the rafters that, "Yes. No, I don't like what you said." Then their speeches would be printed in full in the newspapers. Then they'd be put into pamphlets and distributed all around the country so we got

much more of their actual thoughts than we do today with the sound bites.

Brian: Doris, you've spoken about how much time you spent with other Lincoln books and his original documents to write this book, were there some unanswered questions you were looking to answer by researching this book?

Doris: I think the most important thing I had to do was to bring Lincoln to life for me and was going to take 10 years, which meant he was by my side that entire time. I had to be able to understand what it was like to live day by day during his era. That's why the primary sources are so valuable because you're really reading letters that somebody wrote to somebody else, you're reading oral histories, you're reading descriptions of what it was like to go in the White House.

Do you know what, in the 1860s, anybody could walk into the White House seeking a job. There were no guard stations outside, you could on new year's day, anyone was invited in to bring their muddy boots into shake hands with Abraham Lincoln, and it's that detail that I think you're looking for so that you can feel the presence of these people in the past and imagine that you are actually talking to them even during this period of time.

Brian: Right. What was it about the texture of Lincoln's life, of Lincoln's personality that really became real to you as you were able to spend so much time with this stuff?

Doris: I think there were a couple of things. One thing was that I had known of him as a great statesman, but I hadn't realized what a brilliant politician he was, so many people today could take a lesson from the way he dealt with all these various people, many of whom were in contention with one another. When he made a mistake, he acknowledged it. Easy to do, you know, "Grant, you were right, I was wrong," but how many politicians can do that today? When he got angry with someone, he would write what they called a hot letter.

For example, when General Meade didn't follow up with General Lee after Gettysburg, he knew that the war was going to go on longer and he wrote him a letter saying, "Oh, this is a terrible thing that you've done," et cetera. He never sent it, never signed it. He got it out of his system and he somehow was able to repair animosities.

If he changed his mind on something, he would just say, "I'd like to believe I'm smarter today than I was yesterday." There was so many ways, he had an extraordinary emotional intelligence that allowed him to deal with people, and he kept his decency and sensitivity and kindness and usually, those don't help you in politics, the rough and tumble sports that we think it is, but in the hands of a great politician, they turn out to be terrific political resources.

Brian: You also see him don't you as not just kind and sensitive and empathetic, but also manipulative?

Doris: Manipulative in a very positive sense. Yes. He knew what he wanted. He knew he wanted a constitutional amendment on slavery. He knew he wanted to get to emancipation. He knew he wanted Chase to not win that election in 1864 so he was able-- it never hurt people deliberately, but he certainly understood when to time things, when to get somebody else to go against somebody else. He was a very practical politician, and that made it more interesting for me than if he was just some statesman up in the sky.

Brian: Michael Lind also has a new book on Lincoln, What Lincoln Believed and it takes the position that Lincoln was no racial progressive. He envisioned in America, devoid of Black people who would have left voluntarily for Africa, and he wouldn't have gone to war against the South over slavery. We've heard that before, only over defying federal authority. Do you agree?

Doris: The sad truth is that the overwhelming majority of people who lived in that period of time were racist. There was a prejudice that was built into the North, as well as the South. There were laws in these various States in Illinois. For example, if you were Black, you couldn't sit on a jury. You couldn't vote, you couldn't testify in a criminal defense of your own, so that there was a sense in which-- and even if we look at how long it took when I think about Rosa Parks dying, that kind of prejudice has been still in our country for another 150 years.

Lincoln was no different. One might have hoped he was more spacious than the people around him, but he had some of those same prejudiced views, but the important thing is that once he became president, interestingly, he became very good friends with Frederick Douglass, the great abolitionist.

Douglas at first was very critical of him, but when he met him in person, he said it was the first white man he ever met with who treated him without any sense of color being between them, and he had met with all the great William Garrison. He had met with Wendell Phillips, Salmon Chase, and yet Lincoln was the only one who he felt on an equal level with. I think there's two sides to the question.

Brian: Can I digress for just a minute and ask you to talk because Rosa Parks died yesterday. What are you thinking about Rosa Parks right now?

Doris: Oh, I think what is so extraordinary about her story is we like to say that one person can make a difference in a country, in a mood and in changing things. She by not being willing to take that seat and to stand up. I had such enormous respect for her and to live on in history, very few people get to live on in history in such a positive way.

Interestingly Abraham Lincoln's deepest hope was to create us a story that would be told after he died because he was so afraid of just going to dust and in some ways, that's what impelled him through his earlier suicide attempt, not attempt, but his time when he was feeling so depressed that his friends worried he was suicidal.

It impelled him to go through the war with all the losses and boy, he sure has been remembered, but so has Rosa Parks, and I was thinking that today what a wonderful thing to have stood up for something to have helped to instigate and inspire the civil rights movement and have so many people respect what you did and she was a great woman.

Brian: Is there anything about Rosa Parks that we don't know and should as far as or is it just a simple story of a woman who would not do what was unconscionable for an individual to do?

Doris: I bet if we looked into her past, and I don't know enough about it, that there has to be some reason why she was able to do that when so many other people weren't. What compels somebody to be able to say, "No, I'm not going to take it anymore." Some people say that she was just tired that day, but she said, it's just the opposite. "No, I wasn't going to take it," and I'd love to know more about what it was that allowed her to do that.

Brian: My guest is the historian Doris Kearns Goodwin, her new book about Abraham Lincoln is called Team of Rivals. What are some unresolved Lincoln mysteries for you after all this research?

Doris: I think the one thing that's still extraordinary to me is how he was able as a young man to defy the cultural background from which he came, where reading was considered lazy and indolent and somehow he scoured the countryside for books. He read at the end of a long row of planting, sitting up against a tree. Where does that impulse come from? Somebody has talent. He obviously had talent, but there's so many people who have talent in our country who may never get the chance to realize it. In fact, that was Lincoln's obsession.

There was a poem that he was always haunted by of a young villager with talent who died in an unmarked grave because he never had a chance to escape the poverty from which he came. You always wonder, you hear somebody coming out of the slums, you hear somebody coming out of some very difficult circumstance who breakthrough and to understand how he was able to break through. He had only one year of total formal schooling, just one year, and to be able to write and to read as he did, I'd love to understand where that came from.

Brian: How much did ambition drive that?

Doris: Huge? Because as I say, his ambition was not simply for office or power, it was something so large to make a difference in the world so that he would be remembered. It was almost like a Greek idea that your name can live after you die so long as you accomplish something worthy, and so he certainly did. One of the great things I found at the end was Leo Tolstoy in 1909, went to the caucuses and they asked him all to talk about the great leaders of the West in the middle of these barbarians.

They wanted to hear and he told them about Alexander, and Frederick the great, and Napoleon. However, they said to him, "But you haven't told us about the one man we really want to know about, Abraham Lincoln." Tolstoy was stunned that these barbarians knew the name. He told them all about Lincoln's life, and then he said, in the end, "Lincoln, wasn't a great general like Napoleon. He wasn't a great statesman, like Frederick the great, but he was the humanitarian that's brought us the world and his name will live forever." More than Lincoln could have ever dreamed. His name is still here.

Brian: Did the rivalries, the fact of political competition, which is what, so much of the book or at least is the context for the book, did it help him hone his views?

Doris: I think definitely so. The great thing is when you have people who are controversial and they're offering different points of view, then you sharpen your own points of view so much better than having everybody agree with you. He had the opposite of a friendly cabinet who would say, "Yes, you're right, Mr. President." They would say, "You're wrong," they would argue with each other.

They called each other names. It would be almost impossible to happen today because the newspapers and television would be full of one guy calling another one, a liar and a traitor but nonetheless, there's no question. Roosevelt had the same thing. He had a very contentious cabinet. They would fight with each other and it helped him sharpen his views.

Brian: Why would a president-- oh gosh, maybe it just says something about how times have changed, but I think a lot of people might wonder, why would you want a lot of people around you who would disagree with you, and disagree with each other?

Doris: I think you have to have confidence, number one. He had an enormous internal confidence that even though they didn't think he was up to the job, he knew he was. He figured as he said, at the time, "These are the strongest men in the country." The country was succeeding, falling apart, even then potentially on the verge of a civil war and if he deprived the country of these men's talents, and as long as he could utilize their talents, and they did it. They all were great as cabinet officers. They went down in history. This was their moment in history, but in the end, he gets the benefit from it and the country does as well.

Brian: Of these three rivals, who you're focused on William Seward, Salmon Chase, and Edward Bates, who did you find the most compelling as a public figure?

Doris: No question, Seward. I think what happened is I went early in the research up to his home in Auburn, New York and it stayed in the family for years, and it's been made into a private museum. You can feel his presence there. He was a Churchillian character. He out-drank and-out smoke everybody. He loved to play cards. He loved to have good wine, good food, long dinner parties, where he'd served seven different wines, a man

with a full life force.

The idea as I said earlier that he became a great friend of Lincoln's. When he finally found out-- they didn't want to tell him that Lincoln had died because on the assassination night, they tried to get Seward as well and he was almost killed himself, his whole cheek was knife off his face so they didn't want to tell him and shock him about Lincoln's death, but he finally saw a flag at half-mast, and he said, "I know Lincoln's dead."

They said they didn't know, and they didn't want to tell him, and he said, "I know he's dead. He would have been the first person here to see me after his assassination attempt," and then great tears course down his cheek. That story just really got to me. Those two.

Brian: We're almost out of time, and this quote is floating around out there in the press and on the blogs that you found Lincoln sexy. Where did that come from?

Doris: There's a picture of him in 1848 when he looks like he's got rugged cavernous disheveled hair, and there's without the beard and there's something about the beard that's so imposing and the monument in Lincoln's Memorial makes you feel that he's marble and monument, but he looks alive. I think what I meant by that is that he was vital, magnetic, huge sense of humor and that's what women find sexy. It's not simply his look and his face, but it's that lifeforce which I really felt.

Brian: Now, could a male historian ever write that he found a woman historical figure sexy without being labeled sexist or worse?

Doris: That's a very good question. I'm not sure it just sort of slipped out when I looked at the picture, so I'm being teased about it and it's just fine because I do mean that as vitality and energy.

Brian: This book has already sold movie rights?

Doris: Yes, Steven Spielberg is going to direct a movie based on this.

Brian: Doris Kearns Goodwin's new book about Abraham Lincoln is called Team of Rivals, it's published by Simon & Schuster, and it's been great to have you in the studio. Thank you so much.

Doris: Great to be here. Thank you so much.

Brian: Brian Lehrer on WNYC that was my 2005 interview with Doris Kearns Goodwin, for the day after Thanksgiving history special today, more to come. It's a Thanksgiving weekend history special on the Brian Lehrer Show today as we dig into our archives for some of our favorite conversations with historians, including this one with Ron Chernow from 2017, that first year of the Trump Administration.

[music]

Brian Lehrer on WNYC and with me now, I'm so happy to have the Pulitzer Prize-winning historian Ron Chernow. His Pulitzer was for his biography of George Washington. He also won the National Book Award for his book about The House of Morgan, but you probably know him best for his biography of Alexander Hamilton on which the Broadway musical is based.

Now Ron Chernow has done it again, like with Hamilton, he reintroduces us in his new book to a figure from American history whose reputation he thinks has suffered too much. This time it's Ulysses S. Grant, the Union General in the Civil War who went on to become president, and who oddly is back in the news these days alongside Confederate General Robert E. Lee, as Mayor de Blasio and others decide what to do with their statues, monuments, and tombs. The book is simply called Grant. Ron Chernow, it's an honor, welcome back to WNYC.

Ron: It's an honor to be here. I guess is Faulkner who said the famous statement, "The past is never dead, it's never even past."

Brian: , I guess. Oh well, are you referring to Grant's tomb being reconsidered by Mayor de Blasio?

Ron: Yes. I was stunned as the book was heading towards publication. Suddenly people were saying, "No, Grant is an anti-Semite, and they should tear down Grant's tomb." There's a beautiful equestrian statue of him in Crown Heights. Brian, people know one piece of the story which was that during the Civil War, December 1862, Grant's army is deep in the cotton country of Mississippi.

There's a lot of illegal smuggling of cotton going on, there are a lot of Jewish traders involved, but they're even more non-Jewish traders involved, but not for the first time in history the Jewish are scapegoated. Grant issues what is probably the most anti-symmetric order in American history. He not only bans that Jewish traders, he bans Jews period from the Military District under his command. As soon as Lincoln and Edwin Stanton Secretary of War saw that, they were horrified, they revoked him.

That's the piece that the community [unintelligible 00:24:27] the Jewish community in New York tends to know. What they don't know is what happened afterwards that Grant became, probably the most famous president in American history. He appointed more Jews to Office than all the other 19th century presidents combined.

He'd spent the rest of his life atoning, he began to speak out on human rights violations abroad, the first president to do that in both cases when Jews were being persecuted first in Russia, then in Romania appointed the first Jewish diplomat, with the wonderful name Benjamin Franklin Peixotto to go to Romania to protect persecuted Jews.

Then the most amazing story of all, towards the end of his two-term presidency, he was invited to attend the dedication of an orthodox synagogue in Washington, sat there for three hours with a hat and shawl on, listening to this ceremony in Hebrew, and he was overwhelmingly supported by the Jewish community both times he ran for president in 1868 and 1872.

Brian: Are you telling me--

Ron: I don't think we need to tear down Grant's tomb.

Brian: You'll tell Mayor de Blasio this before they exhume Grant's body? There's something else there?

Ron: I will happily testify. Exactly.

Brian: Robert E. Lee, on the other hand, you're not kind to in the book. In fact, you portray his reputation as wildly overrated after the war, even in the north.

Ron: Yes. It's very, very interesting. If you look at the civil war that Ulysses S. Grant captured three Confederate armies, Fort Donelson in 1862, Vicksburg, Mississippi in 1863, most famously Lee's own army Appomattox Court House in 1865. Probably Lee never captured a single Union Army so why is it that Robert E. Lee is sort of glorified not only as a great general but is this perfect aristocratic gentleman and Grant is denigrated as a filthy crude butcher as a general?

Really it's a political story why that happened and it really goes back to the events in the aftermath of the Civil War when the whites in the south protested reconstruction and the glorification of Lee was part of this reassertion of white supremacy in the south.

Brian: I think one thing that a lot of people have learned because of the conflict in Charlottesville, and the broader discussion about Robert E. Lee statues, is that Robert E. Lee statue in Charlottesville, for example, didn't go up until 1924. It wasn't like right after the Civil War ended.

Ron: Yes, and we know with all of these statues there was a very specific political agenda behind them. The very first one that went up, this was during Grant's second term as President, 1875, a statue to Stonewall Jackson went up in Richmond. 50,000 people turned up, many of them, members of Ku Klux Klan blacks were banned from the rally.

Really what that Stonewall Jackson statue said it was a defined assertion by the white South that reconstruction, in other words, the attempt to create a fully biracial society was dead and that the wide South was back in control. People see these statues and they don't realize that they emerged and quite specific historical context.

Brian: Historian, Ron Chernow, our guest his new book is Grant. [unintelligible 00:27:41] "Ron Chernow, I know that name." Yes he wrote Alexander Hamilton on which the musical was based and now it's Grant.

Ron: I hear it's a very good musical.

Brian: Have you heard that?

Ron: I've heard that from some people that.

Brian: Yes, not bad. You portray grant as believing more in building up the quality of black people than any other president between Lincoln and LBJ?

Ron: Right. Grant had a very difficult task as President, 1869 he becomes president. He's the first president who has to incorporate the 13th Amendment which abolished slavery, the 14th Amendment that promised equal rights, and due process to these four million former slaves who are now citizens, and most controversially he has to enforce the 15th Amendment, which gives black males the right to vote.

It was that 15th Amendment and the right to vote that triggered off the most violent backlash in the south in the form of the Ku Klux Klan for the simple reason blacks constituted more than a third of the Southern population and there were states like South Carolina, Mississippi where they were the majority of the population so that if Blacks dared to assert their right to vote, they were going to come to political power and the Klan was determined that that was not going to happen.

Brian: You just said as an aside, he fought for the 15th Amendment, which gave blacks, at least Black men the right to vote. I'm curious, in your research on Grant, did he take a stand on the women's suffrage movement because Black men got the right to vote decades before even white women.

Ron: It's a very, very good question. Actually, you're the first one Brian who has asked me this because one of the things I tried to cover in the book is the feminist movement of the separatist movement because both Ulysses and Julia Grant were sympathetic to the suffragist movement. In fact, Susan B. Anthony cast her first and only vote for president for Ulysses S. Grant.

It was in upstate New York, it was an illegal vote. She was tried, convicted, and fined. Susan never paid the fine. Actually, the registrar's were sentenced to five days, and Grant commuted their sentence but Susan B. Anthony, Elizabeth Cady Stanton at all

opposed the 15th Amendment, unless there was going to be a 16th Amendment that would give women the right to vote.

It was really the-- the women's movement comes directly out of the abolitionist movement because so many of those women-- it was kind of like what happened here in the civil rights in the 1960s, a lot of women who were involved it's like were fighting for black rights. Hey, what about women, very similar thing?

Brian: Well, maybe Trump's voter fraud commission will use that story as evidence while you see Susan B. Anthony cast an illegal vote. How much does an unfair rap by history tie together you're writing Alexander Hamilton, and now writing Grant because Grant I think has a general reputation, his casual reputation is that he was a really bad president.

Ron: I guess I have a contrarian streak in my nature because when I did Alexander Hamilton, he was either one forgotten or two demonized and Jefferson was glorified. I think that the book and certainly the show helped to rehabilitate his reputation. Ulysses S. Grant, in 1948, Arthur Schlesinger did a poll of presidential historians ranked Grant second from the bottom.

Only Warren G. Harding was considered worse, and it was considered a completely failed presidency, that was marked by scandals, corruption, nepotism, cronyism, you name it. All those things happen, kind of what I try to argue in the book was that that was the minor story of the administration. The major story was Grant's crusade to crush the Ku Klux Klan. He hires a wonderful Attorney General, Amos Akerman, from Georgia. They use the new justice department to bring 3000 indictments against the Klan.

They get more than a thousand convictions, and as Frederick Douglas said afterward, "The slaughter and scourging of my people have ceased." This seems to be much, much bigger story of his administration. It's curious, Brian, what we remember and what we don't remember about presidencies. Why was this whole story buried? Whereas the scandals lived on.

I think it's during Grant's second term in office, the Democrats, the white South, and the Northern sympathizers take over Congress. They were very upset about a reconstruction, which had been promoting biracial society in the South. These democratic investigating committees begin to probe corruption in the Grant administration, and it was really their way of undercutting an administration, and the reason they wanted to undercut it was not because of the scandals, but because of reconstruction, it was considered much to pro-black the administration.

Brian: Defenders of the statues and flying the Confederate flag say the civil war wasn't about slavery. Now that you've been immersing yourself in that area with fresh eyes, that era, how much was it about slavery? How much about state's rights in the abstract or--

Ron: That's a very good question because James Longstreet who was Robert E. Lee's chief commander, James Longstreet said, "During the four years of the war, I never heard anything, but slavery mentioned as the cause of the war." In fact, after the Confederacy was formed in early 1861 Alexander Stevens who was the vice-president of the Confederacy said that the cornerstone of the Confederacy is the idea that the black man is inferior, that slavery is his natural state, and that Confederacy is the first state founded on this great principle.

They weren't shy back then about saying it, it was really just this kind of ex post facto rewriting of history that said it was state's rights. The other thing, Brian is that 750,000 people died in the civil war.

Brian: Unbelievable.

Ron: Hundred of thousands of people died for states rights. However, strongly view listeners may feel about this issue, I doubt that many of them would be willing to lay down their life for state's rights or federal rights or whatever.

Brian: Did the North ever seriously consider letting the South go? Like, what was the point of holding onto the South by force and so many thousands of people dying for that if they didn't share our values or want to be in our club?

Ron: They certainly know there was a segment of the abolitionist movement that said, state slavery is a stain on the nation and let them go and good riddance, but then there were other abolitionists who said that that was simply to condemn the black community in the South to the tender mercies of the white supremacists, and that was kind of became the dominant force, but yes, there were a lot of people who did not want to go to war over that issue.

Brian: What do you make of the events in Charlottesville and things like it, how much of an echo of unresolved issues from the civil war that persist to this day versus how much about new issues that just find their expression in contemporary white grievances and the Confederate flag really means something very different to people today than it did at that time.

Ron: Oh, I think that the civil war is still-- it's an unhealed wound and we're still dealing with the unresolved issues of that because they are these two competing narratives of what happened. After the South militarily lost the war, in many ways, they won the peace. There was a school of thought called the lost cause that began to essentially rewrite history and romanticize the Confederacy.

They said, "No, it wasn't about slavery. It was about states' rights." They argued that it was the Confederacy that was following in the footsteps of George Washington and the American revolution. Most importantly, they said that reconstruction, which we now feel was a noble experiment in American life to try to create a biracial society in the South.

They said that it was a fiasco of corrupt carpet bag politicians and the literate Black legislators. We still have in our schools, these two different versions of what happened. I should say among historians, you can't find a historian who's going to tell you that the cause of the war was states rights, but that is still taught and in many Southern schools and is becoming an article of faith.

Brian: Two little things before you go one, am I right that president Ulysses S. Grant has something unusual in common with President Harry S. Truman. Do you know what I might be referring to?

Ron: The middle initial.

Brian: Middle initial doesn't stand for anything?

Ron: I didn't remember that with Harry Truman. I mean, the story with Grant was that his real name was Hiram Ulysses Grant. He dropped the Hiram because it stuck him with the initials HUG. The kids used to tease him.

Brian: He got teased by the other boys for having the acronym HUG?

Ron: Absolutely. Then he's nominated for West Point by a local congressman who sends in his name mistakenly as Ulysses S. Grant and Grant for the rest of his life said that the S stood for absolutely nothing. Is that true with Harry Truman too?

Brian: I believe that he was just named, I have to double-check this but I believe that he was just named middle initial S without it standing for anything. We looked it up per the Truman library. It's a compromise between the names of his grandfather's Anderson Shipp Truman and Solomon Young So Ship and Solomon the two SS got-- they were inspired by them but it did not technically stand for anything. On his birth certificate, it was just Harry S. Truman. Who's writing Grant the musical.

Ron: I think it's safe to say there won't Grant musical. Grant's life does not move to hip hop beat, but I'm hopeful that there will be maybe a feature film about Grant, but with Hamilton, he was this young dashing romantic figure. Anyway, he was a natural for a show, maybe not natural for hip hop musical, but certainly, Lin Manuel Miranda pulled off this miraculous feat.

Brian: Ron Chernow's new book is just called Grant. Ron Chernow's Thank you very much.

Ron: Oh, this is a great pleasure, Brian. Thank you for having me.

Brian: Brian Lehrer WNYC more to come.

[music]

Brian Lehrer on WNYC. Now my 2003 interview with legendary oral historian Studs Terkel. He had been flown into New York from his beloved Chicago for the grand opening of what was then the brand new StoryCorps booth in Grand Central Terminal. Now, if you're a fan of StoryCorps interviews on public radio, it's a piece of trivia that this was the first official one.

Back then you had to travel to a booth to conduct your interviews. Now you can do it with an app or other at-home technology. It was an honor to get to interview the master five years before his death at the age of 96, I started by asking Studs Terkel what's important to him about the idea of StoryCorps.

Studs Terkel: David Isay, thought of it, a young journalist and it's an accelerating idea. The idea is to have "ordinary" people. I use the word ordinary quotes because I hate that adjective as meaning has a patronizing to it toward, the non celebrated people, the ones who are not in gossip columns, whom we don't see to a [unintelligible 00:39:46] well on radio or hear on TV either way around and about.

Brian: My brother who's an oral historian among other things says the extraordinary ordinary.

Studs: That's exactly it, the ordinary people are capable of

extraordinary things and they are the ones today who live in the sense of surrogate life. To some extent, they do their work. They, men and women, teacher, checkout counter clerk, welder, small businessman, mason, whatever he/she may be, housewife. Somehow live their lives today through someone called Joe Lowe and Ben. I have no idea who Joe Lowe and Ben-- I thought Joe Lowe is a name of a soft drink or something, and Ben is someone who's familiar with Benjamin Franklin but it's not.

It's a couple of apparently limited gifted actors who become the center of attention. Therefore the lives of those other people who created that which we are sitting right now, a table, a chair, a microphone, well, someone invented them but who built it? Whose hands put it together? These are the people who I love to celebrate and [unintelligible 00:41:00] and this whole idea of StoryCorps is to establish kiosks such as newspaper kiosks. We're now at the very first one at the Grand Central Station New York.

Kiosks in different communities in all the cities of the country, dirt road, so the people, ordinary that is the non-celebrated people can walk in, there's a tape recorder, and as a mic with a familiar friend and tell a story about his/her life, something she/he remembers and therefore a disc is presented and that person takes the disc home, and that person's kid or kid's kids remembers it. That to me is quite a very inspiring idea.

Brian: One of the things that people may find daunting about coming here with a relative is that they're not professional interviewers, and they don't know what to ask but David Isay has even devised a question generator which you can use on the computer or just take the pieces of paper to help you figure out what you're going to ask your relatives, but you're the master at this. I want to ask, do you have any favorite questions that you come back to time and again with people you interview or a first question that you usually start with?

Studs: No. I don't believe in questions. I believe in conversation, you must remember that I, myself am a slovenly guy. The other person immediately recognizing me, not someone from Mount Olympus that is 60 minutes or whatever it might be or [unintelligible 00:42:45]. No. No one like that. It's rather someone who is as fallible, as vulnerable as they are. I happen to be very inept mechanically even though I have a tape recorder, and the tape recorder-- my right arm, I press wrong buttons often and I do.

That person sees me fumbling around, that person feels I need him or her, and if you're needed it is essential. I am horsing around now and talking too. The question I suppose, the obvious question is who are you? No. I'm asking you to describe who are you, not simply your name, what do you do for a living perhaps, work, or who are you but there is no one question.

Brian: Who are you? What do you consider core to your identity, to your being?

Studs: What is it? What do you do and why are you doing what you're doing, and would your life have been different had it not been for something that happened? Was an event in your life that made you become a-- God helpless lawyer, or something? I say that because I once attended the University of Chicago Law School.

Brian: This is 93.9 in AM 820 WNYC. My guest from the StoryCorps oral history booth at Grand Central terminal is oral historian broadcaster author, Studs Terkel. His newest book is called Hope Dies Last. We are talking about oral history. I'm going to actually have to do an oral history when we're finished talking. Let me get a few more tips here. Do you think people lie much in oral history, puff themselves up, and tell us what they think they want to hear?

Studs: That's a big question. Sometimes someone always, "Asks how do know they're telling the truth, not lies, but how do you know memory hasn't played tricks on them?" I always think of what preacher Casy, and Tom Joad in Grapes of Wrath, on the road to California, they stop at one of these lodges, one these places there and this guy says, "You're going to California, why to starve to death?

I went, I'm going back home to starve to death." Tom asked preacher Casy, "Is that man telling the truth?" He says, "The truth for him. For us, I don't know." Is that person telling a truth? That person telling what he/she remembers and eventually, you add things up, and basically, it's true. There may be something off in detail.

Brian: So you don't play the investigative reporter and try to smoke them out in an interview? You're just happy to hear a good story.

Studs: No. I'm just assuming they're telling me-- a person remembers the depression and she says-- let's say it's a woman, "Oh, rotten bananas. I can't stand bananas because as the kids we [unintelligible 00:45:50] is rotten bananas." One kid says, "I'm an orphanage," and they would have smashed sardines. "I can't stand sar--" I'm not going to question that. It's a memory you see. Even though it may be slightly enlarged, it's basically true.

Brian: Let me practice on you a little bit and ask you a little bit about Studs Terkel's early life and I'll bet our listeners would like to hear that too. You don't mind right if I ask you a few oral history style questions?

Studs: Ask anything you want. If I don't know the answer, I'll fake it.

Brian: When and where were you born?

Studs: I was born here in New York City.

Brian: You were.

Studs: I was eight years old when I left with my family. My father was ill and an uncle lent us some dough for rooming house mother ran in Chicago. I left here as an asthmatic child. I was a sickly child, and as soon as I hit Chicago, that sounds like a gag I know. Soon as I hit Chicago, my asthma left me. I think it was the [unintelligible 00:46:50] of the stockyard smell that did it but it's true.

Brian: It was all the smoke and that cold air that killed your asthma.

Studs: Somehow, my kind of town Chicago is.

Brian: Did you know your grandparents?

Studs: Oh, yes. I knew my grandmother. That is my mother's mother who was an tough old babe who was once a baker's wife, and [unintelligible 00:47:13]. I remember her. My mother and my father-- How can I explain that? I was the youngest of three brothers, and I was the beloved child. I was the asthmatic little boy. My two older brothers, and my father [unintelligible 00:47:28] my mother did too but she had the gimlet eye that she was out for the brass ring. My father was more of a gentle liberal guy. My mother, she was a tough one. [crosstalk]

Brian: So you were a daddy's boy?

Studs: As I say when my mother died at 87. She hung up her gloves at 87 because she was a fighter. She was taken later on by a crooked [unintelligible 00:47:56]. During the days of the great depression, Chicago had an industrious name, Samuel Insull, big scandal. She was pretty shrewd with dough but apparently, he took her.

Brian: Which of your older relatives, parents, or your grandmother, or whoever, do you think you're the most like?

Studs: Most like? I'm afraid to say, my mother-- I'm across, my mother and my father, she was gentle and socialistically inclined. My mother was more the brass ring out to make it kind, and I suppose the combination, her feistiness I suppose-- my two brothers and my father both died in the 50s of angina.

I had it, she hung up her gloves at 87, and I'm 91. That's something else that has to do with technology. I had a quintuple bypass and that did it. The irony is I'm something of a Luddite. That is I'm just learning the typewriter and it's the wonders of the typewriter as far as I've gone.

Brian: When will you get to the computer?

Studs: I don't know what a computer is. I know it is.

Brian: You said socialistic. Much of your work is grounded in a political consciousness, did you become political gradually or all at once?

Studs: I know it was gradual with the hotel. I told you that my mother ran a rooming house in Chicago. My father recovered, he wanted to work and so we leased the hotel. It's called the Wells-Grand Hotel. It's on the corner of that street called Wells. The name Grand made me think it's great. It's Grand hotel was the famous pre-Hitler hotel of the novel.

The [unintelligible 00:49:40], so the grand hotel more or less was more of my school than the University of Chicago because they have guys-- By the way, it was a working man's hotel, not a flop of working mans and a lot of them were skilled crafts but retired and boomer firemen,

and then came the crash, the Wall Street crash. Then you realize guys are now in the room, in the lobby which I assume is a huge place, but I went to see it not too long ago before it was destroyed. It was a little room but guys were arguing pro, and high labor, stuff like that. That played a big role in my life, I'd say. That was a big role.

Brian: I guess the pro-labor side got you, how come?

Studs: Remember, it was also that I was 18-19 years old when the CIO was coming into being. The Industrial Union [unintelligible 00:50:35], of course, I heard John L. Lewis speak and, of course, he was this eloquent Welshman. The Union played a big role, yes, of course.

Brian: Studs Terkel, my guest as we're still doing oral history in the historical oral history booth at Grand Central Terminal. Are there any sights or sounds or smells that help to define your childhood? You said you're 91. You're one year older than Grand Central Terminal where we're doing this interview, and I was thinking before how much different it must have felt around here in the early days of the Terminal. Do you have any early memories of sights or sounds?

Studs: I have very few memories of New York. It's frighteningly black, but of Chicago, I do. Of course, I do. I remember coming home, coming to Chicago on that trip by myself. I was 9, 10 years old because my father had come here, and my mother. It was day coach and how can I remember? Day coach up all night and the Butchers came in at Buffalo selling cheese sandwiches and milk. Then, I remember even the fight.

There was a prizefight. Jimmy Slattery of Buffalo was knocked out by Jack Delaney, for the light heavyweight title. He picked the buffalo papers when there was a stop between New York and Chicago. I remember that trip and coming to Chicago. Now, this is Sandburg Chicago now. 20-21.

Brian: [crosstalk] Not Ryan Sandburg, Carl Sandburg?

Studs: Do you know that Chicago was the center at his poem. The nation's railway, stacker of which 1,000 passenger trains pass through Chicago each day, 1,000 passenger trains. I remember getting off that train, my brother grabbing me, and how could I forget that? I fell in love with Chicago.

Brian: What's lost from the Chicago of your youth that you miss?

Studs: What's lost is what many cities have lost, a certain kind of uniqueness. For example, thanks to the more and more homogeneity, we have chains, mob pop places. You don't know where you are when you take a plane. When you got off a train, you knew that was the city. The certain landmark. You get off a plane, and you see Red Lobster, you see Marriott, and you see Howard Johnson and this is true story.

I make the tour on books. You know that. I make one of these book tours and so I forget the book. It was about 10-15 years ago. I'm on a tour and I tell the woman, "I'm at a motel." You go from town to town, you got to get up in the morning sometimes to catch an early plane. I say to the switchboard operator at the motel, "Could you wake me up at 6:30 because I got to make a nine o'clock or eight o'clock plane to Cleveland?"

She says, "Sir, you are in Cleveland." That tells me that that's one of the problems with Chicago. The blue-collar city, but with the homogeneity and more and more of, God help us, name the chains.

Brian: With your life experience, do you believe in progress?

Studs: I believe progress comes up. That's the nature of my book, by the way, Hope Dies Last. Hope springs up, does not trickle down. I think a lot of progress comes from the awareness of people, slowly, perhaps. Right now, we're inundated with trivia so much and official deceit that sometimes we're lost, but deep, deep down is why I love this project, the David Isay's project. People can talk and suddenly they'll say things they didn't mean to say that are good. A very quick anecdote that may be telling. It's funny. This is known as pre-association, hope you don't mind.

Brian: You can do that [crosstalk].

Studs: One of the early interviews I did, this woman, she's a young woman in a housing project. To this day, I can't remember if she was white or Black. She was light-skinned and she was very pretty, skinny, bad teeth, because of no dentist. Three little kids are running around, about six, seven, eight. Meantime, I'm interviewing her, She's never been interviewed before in her life. The tape recorder was still a new instrument and the kids want to hear their mommy's voice played back and then jumping up and down.

I said, "You be quiet now and I'm going to play it back." I playback her voice and she hears her voice for the first time in her life. Suddenly, she puts a hand to her mouth and says, "Oh my God." I said, "What?" She says, "I never knew I felt that way before." Now bang, you asked about progress see, that something happened to her, "Wait a minute? Did I say that?" It may have been something racist I don't know what it was, see then that's the kind of stuff I like because it's self-revelation.

Brian: That's my little oral history interview of you. I'm going to go and interview my 88-year-old uncle next for the StoryCorps archive, did I do okay?

Studs: You did fantastic. Your questions, you asked me a key one, how do I know they're lying or making things up? You don't, what you do is you somehow another you ask questions and bet that some truth comes out. Some may be guilted, it doesn't matter is what that preacher Casy said to Tom, that's what he felt.

Brian: Any tips any? Questions that you think I should ask my uncle?

Studs: No, no that's up to you. Ask your uncle how does he feel about you? What do you think of me and tell me the truth? No, there's no one way.

Brian: The broadcaster, oral historian, and author of many books including his new one Hope Dies Last published by the New Press, Studs Terkel, from the StoryCorps booth at Grand Central. It's been my great pleasure, thank you so much for doing this.

Studs: Thank you very much. As the phrase goes, "I like your style."

Brian: I love yours. Brian Lehrer on WNYC, that was my 2003 interview with Studs Terkel from the grand opening of the first StoryCorps booth in Grand Central Terminal. Storycorps.org is still with us of course and you can check out how to do your own interview from home at their website storycorps.org. It's the Brian Lehrer Show on WNYC and it's our day after thanksgiving history special today.

We've dug into our history to bring you some of our favorite interviews with historians and about history, including this one from Kevin Young in 2017 the first year of the Trump administration. He talked about the history of hoaxes and how we still get taken in.

[music]

Brian Lehrer on WNYC. You might know that the word bunk is short for bunkum meaning nonsense or insincere talk, but did you know the word was coined out of racial unrest in relation to the Missouri compromise of 1820 which admitted Missouri to the United States as a slave state? A North Carolina representative insisted on filibustering in favor of Missouri's slave state status in the name of bunkum his home county.

With me now is Kevin Young and he's written a book revealing that and much more called Bunk: The Rise of Hoaxes, Humbug, Plagiarists, phonies, Post-Facts, and Fake News, and in it looks at the history of bunk, and the hoax and calls it a peculiarly American phenomenon from the legacy of P. T. Barnum's Humbug to Donald Trump's fake news of course.

Young finds that a lot of the time racism and race are at the root of why Americans create and believe in bunk. Kevin Young as some of you know is a poet, director of the Schomburg Center for Research and Black Culture here in the city, and the poetry editor of the New Yorker. Welcome back to WNYC, Kevin.

Kevin Young: Great to see you again.

Brian: Let's start with this, what's a hoax? How do you define it?

Kevin: A hoax is something created to fool someone. It's not just a lie, it's much more elaborate than that. Often hoaxers create whole casts of characters, family members, cousins, whomever to support the hoax. I use it as an umbrella term, and I trace in the book, its origins really in the middle of the 18th century to now.

Brian: How is the idea of the hoax connected to race?

Kevin: I don't think it's an accident that our modern idea of race and the term hoax evolved around the same time. When I started looking back on it, it was a hunch but as I started to go from P. T. Barnum to the present, I really started to see it in many, many ways whether it's P. T. Barnum's first big show which was exhibiting a woman named Joice Heth who he pretended was 161 years old, and the nursemaid to George Washington, which really it drew people in and was his first big success to one of his later shows

which was a little bit more troubling, even though there were troubling aspects of Joice Heth. We know she was enslaved and perhaps even by Barnum. A gentleman named William Johnson who had a really long career in showbiz, but it kicked off playing a figure called "What is It?" Barnum purposely made the "It" capitals in order to emphasize that this person, who was a Black man, was this being and it was an 1860, just a few months after Origin of the Species.

It was a brilliant thing to say, in one hand, here's this missing link, "What is this person?", which I think was a very 19th-century preoccupation, but the solution was, it's not a person, it's someone in between, and going from there into the present, we really see how race plays out.

Brian: The Middle East is a place pretty well-known for among many other things, conspiracy theories that things that may or may not have any relation to reality, take root pretty deeply in popular thinking to some degree, but you present the hoax as a particularly American phenomenon.

Kevin: There are American hoaxes about the Middle East. There is that, that happens. What I try to do is think about the ways that American ideas of reinvention and of "You can become anything", which I think are really at the core of our identity here. Also--

Brian: Is that with P.T. Barnum was selling to some degree?

Kevin: He had many sayings, as you probably know, one of my favorites that I quote in the book is, "Every crowd has a silver lining." He very much is looking for the groupthink, I think, that draws people in and these audiences, but I think he was offering almost a democratic notion that people could come and see, "Well, do you believe that this is really a mermaid or not? What do you think? What is it?" There's a lot of questions in Barnum that he's asking the audience to or trusting them or seducing them to think they can answer.

Brian: You tell us that Barnum makes a fascinating distinction between a swindler and a humbug. What's the difference? And why does it matter?

Kevin: One is a good show. I think a humbug provides you a pleasure after, even if you've been fooled. I tried to think about what's that mean today? What's an analogy to going to see a Barnum mermaid that really was a monkey sown to a fish tail. It's a bit like-- reality TV is the closest I came to it, something I watch and enjoy, but we often enjoy it knowing that it's made up or at least constructed and highly scripted, but at the same time, there's a real-- it's even in the name, real impact of reality shows. I think that mix of pleasure and try to figure out what's real and who's next is really analogous to Barnum's humbug.

Brian: Humbug comes up in a Christmas Carol-

Kevin: Buh.

Brian: -buh humbug. Humbug comes up in The Wizard of Oz when Dorothy reveals the fakery. Are they related?

Kevin: I think The Wizard of Oz is great and if I had more space and time, I think I would have thought about it because there was something about The Wizard of Oz that seemed to reference Poe and Edgar Allan Poe had these hoaxes that weren't quite as successful right around the same time as Barnum's very successful ones. I trace that in the book too and the American origins of the hoax, because Poe was really trying to, in his balloon hoax and he had also had a moon hoax, trying to evoke something that would fool people, but they were too artificial there.

They often have this blather that made it pretty obvious, it wasn't describing news. I think the brilliance of Barnum and the brilliance of other people who made hoaxes was that they made a convincing case. They made it seem like news and in the penny papers at the time they exploited that to convince people or at least some of them that it was real.

Brian: To whatever extent Barnum's hoaxes were innocent, you say, by the time you get to the mid-20th century, the hoax becomes more insidious. Why is that?

Kevin: I think because innocence becomes a ploy. I quote James Baldwin where he says, "The innocence is the crime." He's thinking broader about injustice, but I think it very much applies to the hoax where there's a level of innocence being paraded in front of us, and often about race that really is hiding a set of stereotypes or set of divisive issues, which I think the hoax makes a lot of use of. I was struck again and again researching for the book, the ways the hoax makes use of those deep divisions in our culture and sets them going, but also on fire and later it seems so obvious.

Brian: I saw a story that I wonder if it fits into this context for you. Apparently, somebody put out robocalls in Alabama in support of Roy Moore that say, "Hi, I'm Lenny Bernstein from The Washington Post and I'll pay you a lot of money to make up a sexual assault story against Roy Moore." Wow.

Kevin: I think it was even Bernie Bernstein. They went the whole hog and I often see that, not very inventive if you step back and look at it, and obvious, but that's its perniciousness. We believe the hoax. I started out really trying to see like, are hoaxes worse now? Are there more of them? I came to think, yes. But also why now? Why has this happened? I think a lot of it has to do with is deepening of the divisions that we see sometimes every day and even those robocalls indicate some of that.

Brian: Kevin, I see you've included in the book a poem that refers to a hoax that you write about, the Susan Smith hoax.

Kevin: Yes, there's some great poems by Cornelius Eady called Brutal Imagination, great title, where he's thinking, he writes poems in the voice of the made-up person that Susan Smith created.

Brian: Remind people of that story from the 90s.

Kevin: Yes, she, unfortunately, drowned her two children in the back of her car but she claimed that a Black man had carjacked her and ran off with her children. I remember hearing that, I think in New York on the radio somewhere going into a shop and was like, no way that was that true, but it did lead to manhunts and searches of people and a few arrests I think, and could have had big impact. Luckily, one of the detectives was wise about this and poked holes in her story.

What Cornelius Eady has done is imagined the voice of this imagined Black man, there was even a sketch of him, which is really stereotypical looking. I think it's a powerful voice that he's created that thinks about, I think one of the opening lines is, "When called, I come", that there is this stereotypical figure out there that Smith was drawing on. Luckily, these deep divisions didn't hold sway for very long, but it does expose that. I think the hoax regularly does reach for that and touch on that.

Brian: Eady's very short poem was, "I watch another man pour from a white woman's head. Fear he'll live the way I did, a brute, a flimsy ghost of an idea, both of us groomed to only go so far."

Kevin: It's a powerful poem and great book. You should get it.

Brian: I know that you had a run-in with a hoaxer in your life which partly inspired you to write this book. Can you tell us that story?

Kevin: When I was in college, I worked on, Let's Go, a travel guide and the managing editor later became a hoaxer, his name is Ravi Desai and he did a lot of different kinds of hoaxes. I think one of the most prominent was he pledged money to universities, a couple, and created a whole world around that. I think he pledged millions in support of poetry. What a noble great thing. They threw him a huge party, of course, and the party would cost something like $10,000 and that was more than he actually even donated.

When I was working there, he claimed he had cancer. That was really tough later and I talk a little bit about what it means to feel dehoaxed to the go later and have experienced dehoaxing and realize that, wow, I think I was hoaxed then. That's part of the book. It's really about that process of how we end up hoaxed, but also how we can and often do undo that and that can be a tough process.

Brian: John O in the West Village, you're on WNYC. Hello.

John: Good morning. This is a really fascinating segment. Bunk I guess originated as a Southern term, but I'm wondering if Mr. Young could talk about the idea of hoaxes and conmen being viewed more as urban creatures, as the Wiley City people, duping the simple country folk, and if that has implications of the moral worth of dangerous city people and pure country folk who are getting deceived. I'm wondering if you could speak of urban versus rural as it plays into this idea.

Kevin: That's a great question. I do think in the 19th century, certainly, there was this idea and even guidebooks warning folks who were coming newly to the city to be on the lookout for conman and conwomen and I traced that a little bit in the book. I do think that country folk who I count as my family and loved ones are very sophisticated. I hesitate to make that clear-cut distinction. I do think that in American history there is this notion of "You get off the bus in Hollywood, or in the Big Bad city and you get taken away," but the hoax is a bit more elaborate than that. Isn't just citified ways that lead to the hoax.

I do think there is this notion that the hook sometimes sells of sophistication, though, and we could maybe think about the ways that hoaxers offer a more refined world, but often when I started to poke at and prod at what was lying beneath the surface, there's often a real crude over-the-topness to a hoax, something like James Frey's fake memoir, A Million Little Pieces is very, very, dramatic and lots of blood and gore and guts. That's not exactly a city or a country, it's deeply American, this trauma that Frey is selling us as a triumph.

Brian: There are several, including Frey's, fake memoirs that you refer to. Is that a category in and of itself?

Kevin: Sad to say it is. In fact, there's a moment I say in the book, that someone used a nonfiction memoir, and I saw that term use, I'm like, "That's a terrifying term because memoir is meant to be nonfiction." I do think this has eroded some and we've lost a sense of, and my book asked why, of what the truth is. I think the danger for me, I started to understand, isn't just the truth, though, I think the hoax does damage that in the fake memoir, especially, but also to the idea of art.

The idea that art could change us, and that something made up the imagination is enough, and now I think it's also a version of reality to television that sometimes we limit the self to autobiography when the self is full and exciting and imaginative.

Brian: Constantine in Brooklyn, you're on WNYC with Kevin Young. Hello.

Constantine: Hi, thanks for taking my call. I just wanted to just speak a bit about the hoax as possibly being revelatory, or breaking boundaries. About eight years ago, I just finished a master's in literature in England, and I was interested in how literature could be innovative now, and I looked at our times, and I thought, "Well, real-time technologies and reality show culture." I hosted an online literary reality show where the contestants, their identities were anonymous, and they were judged purely on their writing.

I would make videos in which I would announce a literary challenge, and the 12 contestants would each start the novella, and then they get voted off every 10 days, and I did [unintelligible 01:12:58] who got voted, and it acquired quite a following and an international one, not a big one, but a very devoted one. Then at the end, the last person, the final post, basically, I revealed that I was writing all 12, all the different styles.

[laughter]

Kevin: I see, a trickeration.

Brian: Constantine, what's the moral of the story?

Constantine: Well, for me, it was never meant to be a hoax. It was trying to create something new. I got swept up in it myself. Some people felt deeply betrayed, and it was really hard for me afterwards, because of that, because I grew close. The real characters, in the end, were the commenters, because they were interacting with the contestants and write comments, and get in fights. It was just an incredible relationship we developed.

Kevin: That's fascinating. Yes, I would love to know more about that later, but I think for me it really shows the way that the audiences quickly become invested in the realness of what they're presented. I talked a little bit about the pact that art makes or fiction makes, and I think of it very much as related to fairy tales were told as a child. You can have them be wild and do also things and that they're filled with danger and betrayal, like the grandmother can become a wolf, but the grandmother telling the story can't then turn out to be a wolf even if that's the anxiety of the fairy tale expressing.

There's this contained quality in the tale itself, that lets you be wild, but we do have this reaction when we find out that the storyteller isn't who the storyteller says they are. Now, of course, this is the start of the novel, in some ways, and I trace that too, and I don't think it's an accident that the hoax and the novel come around the same time, but they take very different paths, and a novel that lasts has to rely on its words and many times when hoaxes are exposed, it becomes really clear that they don't stand up without that autobiographical propping of the fake story around it.

Brian: You write in the book that "post-truth" and "alt-right" are not only euphemisms but synonyms. Why?

Kevin: Well, I think that this idea of-- Well, even the "alt-right" is a euphemism, it's something made up to cover the issues that 10 minutes before would have been called white nationalism or just straight racism. I think it's a confusing moment when the words are getting in the way of the meaning of the thing, and that's, I think, the danger of what I call "the age of euphemism", and post-facts, and what now gets called "fake news" often just means "News I don't like" or it's an accusation against factual, provable things like that Obama was actually not president during Hurricane Katrina say.

Instead, you see people really invested in things that are provably untrue, and the question I wrestle with in the book, is it harder now? Has the internet changed things? How has technology affected us? How is our need for narrative, which I think is very much part of this, being manipulated or played on and satisfied, perhaps too easily by the hoax?

Brian: Here in the Trump era, in the final pages of the book, you've put forth the notion that the truth might not be an absolute relative, but a skill, a muscle like memory, that we've neglected so much, that we've grown measurably weaker using it. Do you think we can rebuild that muscle?

Kevin: We can rebuild him. I do think that--

Brian: Him?

Kevin: That's a The Six Million Dollar Man reference from the '70s. Sorry. I think we can build it. The truth, I think, is something that we can, but I do think it's going to take some effort and some honesty, about how we got here, about what hoaxes are really about, and I think that so long, people said they were just Fact or Fiction. It was just about this blurry line. When the truth is, that line isn't that blurry. I found time and time again, that people really reach for these stereotypical ideas, things that are shorthand that let them make the hoax possible, and then once revealed, the hoax really reveals other things about what we deeply believe, and sometimes it's the worst about each other.

Brian: Forgive me for not getting The Six Million Dollar Man reference.

Kevin: Sorry, I've got a lot of '70s TV in there.

Brian: I'm deeply humiliated. We have about a minute left, what's going on at the Schomburg?

Kevin: Well, it's an exciting moment. We just went through a multi-million dollar renovation, and we're open for business, and we have gotten some really great acquisitions lately, including the James Baldwin archive, which has just been tremendous. Also, the Sonny Rollins papers, those are being processed right now, but involve home recordings and various things of this super genius.

Brian: Are you part of the movement to rename the Williamsburg Bridge for Sonny Rollins who famously played there?

Kevin: I would throw my vote in that camp, but I think we're really excited about the idea of bringing home to Harlem, these figures who, in Baldwin and Rollins's case, were born and grew up there, and looking ahead to doing that in other ways and bringing the Black cultural capital of the world that is Harlem, home and again, in many ways.

Brian: How can the public interact with the Baldwin material? They can go there and read it?

Kevin: Anyone can come and see it. Please do and we have pop up shows from time to time, so please visit us up on 135th in Malcolm X Boulevard.

Brian: Kevin Young, generating so much stuff on so many levels for New York right now and for the world as director of the Schomburg Center for Research in Black culture, as The New Yorker poetry editor, and as the author of the new book, Bunk: The Rise of Hoaxes, Humbug, Plagiarists, Phonies, Post-Facts, and Fake News. Thank you so much for coming downtown.

Kevin: Thanks.

Brian: That was my 2017 interview with Kevin Young for this Day-After-Thanksgiving History Special today. More to come. It's a Thanksgiving Weekend History Special on The Brian Lehrer Show today, as we dig into our archives for some of our favorite conversations with historians, including this one with Sarah Vowell from 2015. We won't be taking your calls but you can continue the conversation on our website at wnyc.org, click on Brian Lehrer Show, or on Twitter @BrianLehrer.

[music]

Brian Lehrer WNYC. You think the Pope drew crowds. New York once had a visitor from overseas who got over half the population of the city to greet him. I'm talking about the subject of my next guest's book, the Marquis de Lafayette. All right, that means about the same number of people has got free tickets to see the Pope drive through Central Park, but on a percentage basis, no one has topped him since he returned to the US to mark the 50th anniversary of its founding, the Marquis de Lafayette.

Sarah Vowell joins me now to talk about her book Lafayette in the Somewhat United States and as you can tell from the title, she again brings her inevitable take on American history that you may know from her appearances on This American Life or her books like Assassination vacation, The Partly Cloudy Patriot, or The Wordy Shipmates. Welcome back to WNYC, Sarah Vowell.

Sarah Vowell: Good to here, Brian.

Brian: Of all the historical figures we never think about anymore, why the Marquis de Lafayette?

Sarah: Like you said, he was just so beloved and for good reason. I think when he came over here in 1777, he was this 19-year-old kid who came over to volunteer, partly because he wanted an adventure, like all 19-year-olds, and also the British had killed his soldier father in the previous war so he had a little bit of a grudge. Even though he was this aristocrat who came over from Paris and Versailles, he really just rolled up his sleeves and pitched in and endeared himself to Washington and the men and ultimately the American people.

Brian: We'd like to think about George Washington and them, but I think people forget that the war was won, in large part, thanks to the French fleet.

Sarah: Oh yes. We would be speaking English right now if it wasn't for the French.

Brian: We're certainly not doing that.