The Worst Measles Outbreak in 20 Years

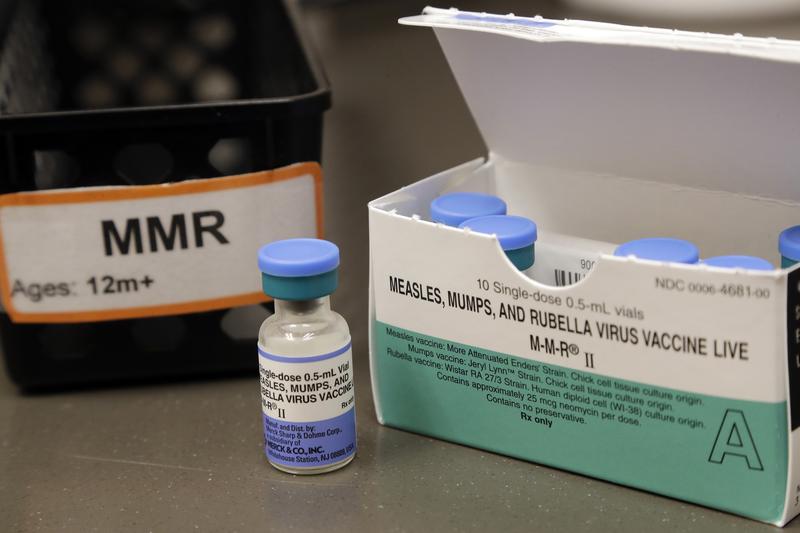

( AP Photo/Elaine Thompson / AP Images )

Amina Srna: It's The Brian Lehrer Show. I'm producer Amina Srna filling in for Brian today. Good morning again, everyone. Now we're going to take a look at the biggest measles outbreak in the United States in more than 20 years. For decades, the US has held what's known as measles elimination status. That designation was granted in 2000. It doesn't mean measles disappeared entirely. It just means the virus wasn't spreading continuously in the country for more than one year. That status might be in jeopardy.

Over the past year, over 2,200 people have been infected and 3 people have died. Those are the first measles deaths in the United States in a decade. This resurgence comes amid several overlapping shifts. Childhood vaccination rates have fallen nationwide since the pandemic, driven in part by rising vaccine skepticism. At the same time, the federal government has cut billions of dollars in public health funding used to track infectious diseases and respond to outbreaks.

Earlier this month, Health Secretary Robert F. Kennedy, Jr. Announced major changes to the childhood vaccination schedule, reducing the number of routine vaccines from 17 to 11. Apoorva Mandavilli covers science and global health for The New York Times, and she's joining us now to help understand this current measles outbreak and how we got here. Welcome to WNYC, Apoorva.

Apoorva Mandavilli: Always a pleasure to be here. Thanks for having me.

Amina Srna: First, can you tell tell us about how bad this past year has been compared to previous years? How many more cases are we seeing?

Apoorva Mandavilli: We've seen so many more cases than we normally do. As you mentioned, there have been 2,200 cases in 2025, and that's the most cases we've seen in about 30 years since the 1990s. That in itself is alarming. Then what's really been worrying public health experts is that they think this is one outbreak that started in Texas last year that has continued on uninterrupted, starting new outbreaks in Utah and Arizona, on the border between those two states, and now in South Carolina. If that's the case, that's this one outbreak that's just continued on and is still going, that means that we as a country lose that measles elimination status that you were talking about.

Amina Srna: You talked about Texas and South Carolina there. How does New York compare to other states?

Apoorva Mandavilli: New York has had cases here and there. You may remember a few years ago, we had a pretty big outbreak in the Orthodox Jewish communities. We have not been a big part of these recent outbreaks fortunately. It is always a reminder, I think, that when you see measles cases elsewhere, that wherever there are pockets of low vaccination, and we know that we have some pockets of low vaccination in New York, it's always a possibility that we will also see big outbreaks here. All it takes is just one case to come into a community with very low vaccination rate, and it can very quickly take off because measles is just about the most contagious infectious disease.

Amina Srna: Listeners, we want to hear from you on this. Has there been a measles outbreak in your community and how are people responding? If you're a parent, what is the protocol at your school? Are you nervous about infection even if your kid is vaccinated, or maybe your kid isn't vaccinated and you want to share your concern or reasoning. If you've ever crossed paths with measles, we want to hear your story. 212-433-WNYC. That's 212-433-9692. We'll also be talking a bit later on in the segment about the flu, and looking for your stories on that as well. Are you vaccinated but still recently got it? Are you unvaccinated and maybe you got it really badly, or have you managed to avoid it and have any tips for the rest of us? Call or text at 212-433-WNYC. That's 212-433-9692. Apoorva, we saw that last year, Canada lost its measles elimination status because of an outbreak. Is this a global trend or maybe just a North America trend?

Apoorva Mandavilli: To a certain extent it is a global trend. Measles has been back on the upswing in many parts of the world, including Europe, including many parts of Africa, where it never really went away, being a problem. As you mentioned, yes, Canada lost its elimination status. Mexico is also potentially going to lose its status. There's a lot going on in the overall, but there's no doubt that, in the US, we have seen a rise in vaccine skepticism and a drop in measles vaccination rates. That began right around the pandemic when there was a lot of disruption to medical services nationwide.

Then the backlash against COVID vaccine spilled out into vaccines generally. We've seen a drop in measles vaccination rate in this country. You're supposed to have 95% for what's called herd immunity, to protect the community at large. We've now dropped into something like 92.5%, which doesn't sound like a lot. It's a couple of percentage points, but really translates to hundreds of thousands of kids who are unvaccinated.

Most importantly, there are a lot of pockets all over the country where the vaccination rate is below that herd immunity. Before the pandemic, about half of counties in the United States had enough vaccination rate, that 95% rate, to keep the community protected. Now that's fallen to something like 28% of US counties. Millions of kids now live in American counties where the vaccination rates are too low to have herd immunity.

Amina Srna: Before I ask you a bit more about why those vaccination rates are lowering, briefly, what actually happens when that designation is removed from a country? Does it affect travel or anything else in the day to day?

Apoorva Mandavilli: It doesn't have a lot of practical implications. It's really almost like a source of pride or lack of, in this case. For a country like the United States, as wealthy as we are, as much of a leadership position we have in the world, to lose measles elimination status. This is really quite embarrassing, ultimately. I think that's how most public health experts see it. The other thing, of course, is that because there is so much anti vax sentiment now and skepticism of vaccines generally, that it's going to be really hard to get back to a place where we can regain that. We may stay a country that doesn't have measles elimination status for a long time. That's just not a position you want a wealthy nation like the United States to have.

Amina Srna: How many fewer people are vaccinating their children compared to pre pandemic times? Where do we see that happening the most dramatically?

Apoorva Mandavilli: It's happening really across the country. It's not one of these things where you can say, this state in particular, or this part of the country in particular. The way that vaccination status works, when you look at it by county, you can see that a particular state may have a very high vaccination rate. Then when you drill down into the county level, there are pockets, or there are certain schools that have really low vaccination rates. States require vaccinations for daycare or entry into kindergarten. A lot of states have pretty strict requirements, and they're pretty even across the country. They're very similar across the country, across red and blue states.

Different states offer exemptions. Some states offer exemptions on the basis of personal beliefs, but those are rarer. Pretty much all states offer medical exemptions. If your child has a medical condition that doesn't allow them to get the measles vaccine because it's a live, weakened virus. Some kids just can't get it. That's another possibility. There are lots of things that are built in for people to opt out. If you homeschool your kids, you may not vaccinate your kids. When you start drilling into the very local areas, you start hitting upon religious communities or communities that are bound by other philosophical commonalities that have low vaccination status. That's really where you start to see these outbreaks catch on and spread.

Overall, we are seeing vaccination rates-- the confidence in vaccination drop across partisan lines. That's really new, because traditionally, we've had very strong bipartisan support for childhood vaccinations. Over the last few years, we've seen that Republicans are falling off of that a little bit. In the last year in particular, there's been a lot of rhetoric around the safety of vaccines.

There's a lot of rhetoric from the health secretary, Robert F. Kennedy, Jr., and from other federal health officials that vaccines haven't been tested properly, that they were not tested against placebo like they're supposed to be, which is not true, by the way. Based on those comments, I think there has been more worry about the safety of childhood vaccines. Now something like 50% of Republicans apparently don't quite trust that vaccines were tested properly. You are starting to see some of that partisan divide. In terms of vaccination rates, we haven't seen massive drops just along partisan lines quite yet.

Amina Srna: A texter points out, "RFK did not actually take the measles off the vaccination schedule." We'll dig into that in a little bit later. First, why have these rates been plummeting even before this revised schedule?

Apoorva Mandavilli: We have seen anti vax sentiment just across the board for many years now. Pediatricians, if you talk to them, will say we've been having more and more questions about this in the last many years, even just prior to the pandemic. The pandemic, I think, really made things much worse because there was so much backlash against the COVID vaccine. There was so much mistrust of the vaccine. People felt they were being lied to about what the vaccine could and couldn't do, about whether the vaccine had side effects or not.

You started to see the rise of these very powerful people with very powerful voices talking about how the COVID vaccines were dangerous and deadly, including Health Secretary Mr. Kennedy. He himself also said that the COVID vaccine was the deadliest vaccine. You saw a lot of this talk about vaccines, and I think that really affected childhood vaccinations also, and they just have not really recovered. We're starting to see a downslide, and that downslide seems to be getting worse rather than improving as public health experts had hoped. They hoped that as the pandemic resolved, those vaccination rates would come back up, and that just has not happened.

Amina Srna: We're getting a few texts with very specific concerns. One texter writes, "I'm a teacher at a school and I worry a lot about unvaccinated kids because I just had a baby who is too young for many vaccines." Another listener writes, "I'm terrified of measles, was vaxxed as a kid, but I have no more immunity and I can't get a booster because it's a live vaccine and I'm immunocompromised."

I know, Apoorva, you were just speaking about kids who are immunocompromised and potentially could not get the live vaccine. There are also adults like our listener who fall into that same category. The Department of Health and Human Services has been cutting a lot of federal grants to local health care centers, which has ended up restricting vaccine access. Can you talk a little bit more about that?

Apoorva Mandavilli: A lot of health departments were relying on some funding from COVID 19 grants that were supposed to run through this summer, and those were taken away pretty abruptly last year. A lot of health departments ended up having to get rid of people that they had employed and they hadn't yet made plans to cope with that loss of funding. In general, there has been less funding to health departments. There's been less funding to the CDC, which gives out money to local departments. There's less assistance from the CDC because there are fewer people working at the CDC.

Just in multiple ways, there are effects on local health departments. What your readers or what your listeners have said about the effect on immunocompromised people, I think that's really important, because one really big shift I think we're seeing with these new policies from the current health department is that the focus is very much on individual autonomy. They've said repeatedly that what they want is for people to make the choice to get vaccinated, but that really doesn't take into account these situations where adults or children are immunocompromised.

It doesn't take into account situations where a child is too young to be vaccinated, for example, or with the MMR, pregnant women who may get exposed to German measles, or rubella, as we call it. There's just all these consequences of the new policies that haven't fully been fleshed out. When you just make things seem as if they are really only beneficial at an individual level, it takes out the community effect of vaccination. It's one of those public health goods that's really most powerful when you see it at a community level. That, I think, is what we're starting to lose.

Amina Srna: Apoorva, we have a text that says, "Please say something about why measles is a concern. We don't all know diseases," and I agree. Fair point. Can you tell us why measles is a concern, not just for little kids, but for older adults as well?

Apoorva Mandavilli: Measles, I think people think of it as just this rash and this inconvenient fever and then it goes away and you're fine. It can actually be deadly in some cases. It can also cause encephalitis, which is brain inflammation. One really bizarre thing about measles that wasn't really appreciated until relatively recently is that when a kid has measles, it wipes out your immune memory. It basically takes away your body's recognition of other things that it has been exposed to before. If you've had something like chickenpox or some other virus that you've been exposed to before, your body basically loses that immune memory. When you're exposed to it again, it's like you just become exposed to it for the very first time.

There have been analyses showing that measles, directly or indirectly, was responsible for a lot of childhood mortality, directly from measles itself, but indirectly by weakening the immune system so thoroughly. It can also cause side effects, years after a child has recovered. That's not very well appreciated either. In most cases, measles may not cause really severe problems, but for a minority of people, it can be quite dangerous.

Amina Srna: We have a caller on this. Let's go to Ellen in Nayak. Hi, Ellen, you're on WNYC.

Ellen: Oh, hello. Thank you for taking my call. I just feel so strongly about this, and I'd like to testify. In the 1950s, before there was a measles vaccine, I got a very bad case of measles. Almost 70 years later, I still remember it. It was the sickest, I think, I ever was. I had hallucinations, very high fever. My mother nursed me rather than send me to the hospital. It's a horrible, horrible disease.

It kept me out of school for months. I still remember the sickness and the fever. I just would never wish this on anybody else. If there's any way to prevent it, I certainly don't understand why people don't do it. It really is a horrible disease. I guess as you were talking, it's been undervalued. I just can't stress enough that if anyone, children or adults, can avoid getting it, they should definitely do that.

Amina Srna: Ellen, thank you so much for sharing your story. Apoorva, this does come up a lot. The idea that maybe the living memory of measles is far away for a lot of parents. Maybe they themselves didn't experience this, and this impacted an older generation very directly. As somebody who covers this, is that something you think about?

Apoorva Mandavilli: It's very much what I think about. I'm also a global health reporter, and I go to countries where measles is very much still a big problem. As Ellen was saying, I think people don't fully understand that it can be very serious. 1 in 9, 1 in 10 people can be hospitalized with it. It's not trivial for a lot of people. We've seen three deaths from measles in this country in the last year, and that's the first time in a very long time. It can happen when measles starts to really spread.

I think one thing that I've been coming across a lot is that pediatricians don't necessarily know how to recognize measles. Several years ago, I wrote a story about this clinic in Massachusetts where there was one doctor who had seen measles because she had worked abroad and was able to catch a child who had come into the waiting room. It took them one whole week to make sure that they got to all the people who had been exposed to make sure those people were all vaccinated. Because it's so contagious, it can be really difficult to contain measles. If you don't have doctors who know what it is on site who have had some experience with it, it's going to be really hard to get to those cases early enough.

I keep hearing from pediatricians that a lot of them had never seen a case in training, are just starting to see them and just starting to understand what it looks like and how to distinguish it from other rashes. I think that's going to be a problem with other childhood diseases as well. We have a whole generation of pediatricians who are not used to seeing these diseases.

Amina Srna: Let's go to another call. We're getting a couple of grandparents texting and calling in. We'll go to Nancy out in Selden, Long Island. Hi Nancy, you're in WNYC.

Nancy: Hi, thanks for taking my call. I'm a grandmother taking care of, just once a week, my grandson who has had his, I guess, one vaccine for measles. He hasn't gotten a second shot. I don't know what the schedule is. Then I'm actually flying to Florida where I've been surrounded by anti vaxxers with young children who haven't been vaccinated at all. I'm concerned. How concerned should I be?

Amina Srna: Nancy, thanks so much for for your call. Apoorva, just before you answer that, a similar question. A texter writes, "I'm a senior citizen vaccinated against measles in the early 1960s. I've read conflicting articles that say it would be a good idea after all these years to get a fresh shot, while others say not to bother. Can you clarify?" Have you come across this in your reporting?

Apoorva Mandavilli: Yes, it comes up a lot, and I hear from readers as well. I think there are, unfortunately, two trains of of thought on this. One is if you have been vaccinated, for the most part, the vaccine does wade off a little bit, but that you should be covered. People have been going to get antibody titers. There's some thinking that even if you don't have any visible antibodies, if you remember from COVID, that antibodies are just one part of your immune system. Even if you don't have antibodies in your blood, that doesn't mean that there aren't other parts of your immune system, what we call T cells and B cells, these other components of the immune response that still remember what measles looks like and will kick in.

That said, there's no harm from getting another booster dose if it makes people feel better. I have heard doctors say go ahead and get one. It's not a problem to get another dose. As far as a child who's had one dose, one dose still offers quite a bit of protection. Two doses are obviously ideal, but even with one dose, they should get a fair amount of protection from the measles virus.

Amina Srna: Here's another text that goes to what we were talking about earlier. "I think a lot of people don't vaccinate because they've never seen anyone with the diseases that we vaccinate for. I think if anyone saw a person or a child with polio, they might think twice about not vaccinating." Here is a caller with a similar point. Paula in White Plains, you're on WNYC. Hi, Paula.

Paula: Hi. Thank you for calling. I'm a longtime listener. I mean, thank you for taking my call. I am 80. Why that is germane is that when I was a child, there were no vaccinations. I got the chicken pox and I got the mumps and measles [unintelligible 00:20:56]. I continued to get sick for a year. I was really sick for a year. I got inflammation of the brain covering, and I was really sick from that. That I remember. I do remember the hallucinations, although they were-- [chuckles] I'm okay with those.

The real message here is that because of the inflammation of the brain covering, I have learning disability. That is pretty documented today, not when I was a child. I struggled in school, and my personality changed, according to my mother, from the time before I was sick until after I got better, which took a year to do. I feel so strongly about the reason why children need to be vaccinated. I think the caller who said that people haven't seen the harsh results of not getting vaccinated, they don't really know. They don't really understand. I really understand. That's all I wanted to say.

Amina Srna: Thank you so much for your call, and thank you for that testament. Let's go to another call. Lori on Long Beach, Long island, you're on WNYC. Hi, Lori.

Lori: Hello. Thank you for taking my call. I'm a registered nurse. I work as a school nurse. While vaccines are important, it's also important that vaccines be given safely according to one's genetics. We need more genetic testing. Measles in particular would be safer given in divided doses. If a person had a measles vaccine, and a few months later a mumps, and a few months later a rubella, they would have less reactions.

We're only talking about the disease part. We're not talking about all the people who have had reactions to vaccines, and serious ones. When Europe went back to offering the MMR in divided doses, after four years of using an MMR and seeing more emergency room visits, we have to follow suit and not think of cost effectiveness. Children who have genetic-- Yes.

Amina Srna: Yes, sorry, finish your point.

Lori: I was going to say children should have genetic testing before they're given so many vaccines from birth on. Children who have a gene for a seizure disorder should be vaccinated on a different schedule. Children who have genes--

Amina Srna: Lori, let me get a response for you from our guest. Apoorva, I imagine you would want to respond to that.

Apoorva Mandavilli: Yes. There are no vaccines or drugs that have zero side effects, but the MMR combination vaccine has been in use for decades, and it's been studied extensively. There are no side effects that are serious for the vast, vast, vast majority of kids. I don't know about the specific genetic background that would cause a kid to have seizures, but in the vast majority of cases, it's actually more dangerous to not have the vaccine. As we've been hearing from the other callers, measles is not a trivial disease. By delaying these vaccines, by delaying measles and then having mumps separately, and all of the vaccines given separately, you're essentially exposing kids to those diseases without the protection of a vaccine.

I think that's something you hear about a lot when you go to other countries. It's something you hear about, in general, when the vaccines are not easily available, is that it's easy to focus on the side effects of the vaccines when the diseases are not a threat anymore. I think people have, to a certain extent, forgotten the threat from the diseases themselves because we haven't seen them be a huge problem in this country for a very long time. We're just starting to see the beginnings of measles again, but there is a lot of potential harm from delaying vaccines by splitting them and waiting to give them one at a time.

Amina Srna: The Health Secretary has expressed a lot of skepticism about the shot, the MMR shot specifically, but it wasn't one of the vaccines that was removed from the list. Why not, and do you think that's coming?

Apoorva Mandavilli: I can't speculate on whether it's coming, but I can say that he has said that measles vaccine is important to prevent the disease. He has also, though, said that the measles vaccine has fetal debris, that it causes deaths, that it causes the same symptoms as the disease itself. Those things are all untrue. He has also at times backtracked and said, no, no, that it is actually important to get the vaccine.

So far, it's stays on the list. We know one of the things they said when they introduced this new schedule is that they are going with what they call the consensus vaccines. This is a vaccine that the world across the board really strongly endorses, is a very important one. I think not having that on the schedule would have made the US outlier by a mile. I think that's not something that they're going for.

Amina Srna: In our last few minutes, I want to ask you about something you reported on earlier this month. Several medical organizations, including the American Public Health association and the American Academy of Pediatrics, are asking the courts to throw out the revised vaccine schedule. What's the basis for that case, and what's the likelihood that they'll have any success?

Apoorva Mandavilli: It's hard to say where that will end up. They actually originally filed a lawsuit after the Secretary unilaterally announced that he would be restricting access to the COVID vaccines. Then they've added this on as the health Department added more things on and introduced this new schedule. Their argument is essentially that this is not based on science. This is dangerous. They actually call it reckless, and they say that it really threatens the safety of children.

Normally, when vaccine recommendations are made, they're made through this federal vaccine advisory committee that very carefully looks at the evidence over months, sometimes years, and makes these decisions. In this case, we had a couple of federal health officials who talked apparently to a couple of health departments in Europe and came up with this schedule. They are basically saying this is very unscientific, this is dangerous. They want this new federal advisory committee that the health Secretary put in place, they want that committee to be stopped, their meetings to be stopped, and they want this new schedule to be revoked and to go back to the original vaccine schedule as of last year that the American Academy of Pediatrics still endorses, and for the most part, that most states in the country, the insurance companies, everybody's still following that old schedule. These organizations are essentially asking the courts to say that's the legitimate schedule. We want this new smaller schedule that the health Department came up thrown out.

Amina Srna: Apoorva Mandavilli covers science and global health for The New York Times. Thanks so much for joining us today.

Apoorva Mandavilli: It's my pleasure. Thank you.

Copyright © 2026 New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.

New York Public Radio transcripts are created on a rush deadline, often by contractors. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of New York Public Radio’s programming is the audio record.