The Politics of Jerry Garcia

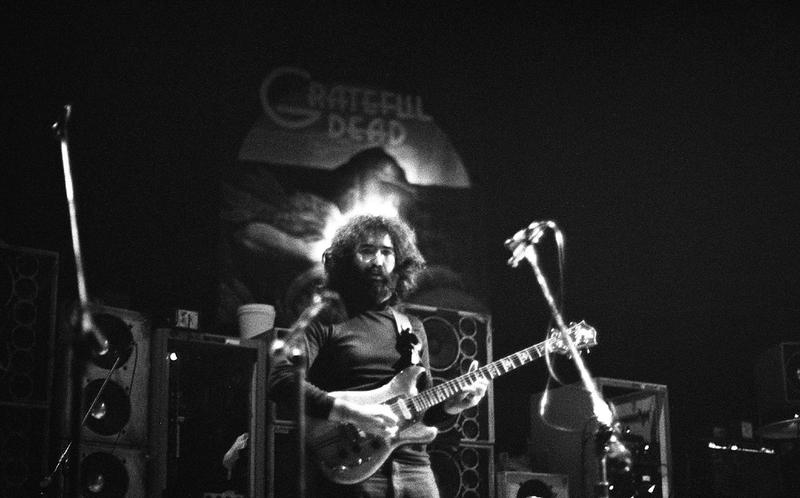

( flickr: Grant Gouldon )

[MUSIC-

Amina Srna: This is The Brian Lehrer Show on WYNC. I'm Amina Srna, a producer here on the show, filling in for Brian today. This month marks the 30th anniversary of the passing of Jerry Garcia, the band's iconic frontman. Beyond their music, Garcia and the Dead are perhaps best known for their role in the counterculture revolution of the 1960s and beyond. Even though the band played in support of political groups and causes, Garcia personally disdained government, preferring instead, "Communes, collectives and self-contained organizations." That's according to our next guest.

We're joined now by Jim Newton, editor of Blueprint Magazine at UCLA, where he teaches communication studies and public policy, and the author of a new book, Here Beside the Rising Tide: Jerry Garcia, the Grateful Dead, and an American Awakening. Jim, welcome to WYNC.

Jim Newton: Thank you so much. It's a pleasure to be with you.

Amina Srna: For listeners who may not be familiar with the Dead or are familiar, but just don't get it, can we start with a little Dead one-on-one? They emerged as a band in the mid-'60s in San Francisco, and maybe the song we just heard, Friend of the Devil, maybe we can use that as a way to talk about their style of music.

Jim Newton: Sure. As you say, they started really with what were known as the Acid Tests in 1965 and 66 in and around San Francisco and developed this fusion of musical styles, some of which are captured in the clip you just presented. It's a hybrid of bluegrass and folk and country and rock and roll and jazz, a very distinctly American musical idiom that they played and played quite successfully for 30 years. Here we are, as you said, 30 years after Garcia died, still listening to it, still enjoying it. It's really had a very durable effect on the American music landscape and listeners.

Amina Srna: Any Deadheads out there listening, how do you see the political legacy of the Grateful Dead and Jerry Garcia? Did the hippie ethos of the 1960s influence your relationship to community building or your personal politics? 212-433-WNYC. That's 212-433-9692 or really anything you want to share about the Dead, their music, or maybe just how many shows you've been to. I know Deadheads are famous for their commitment to seeing the Dead live. Maybe we can get a bit of a contest going here. Who in our audience has seen the most Dead shows? Any of you out there call in to brag or explain the appeal. 212-433-WNYC. That's 212-433-9692. You can also text.

Just in case it went by too quickly or people are not familiar, I said I called for Deadheads. Jim, before there were Taylor Swift's Swifties, fans of the Grateful Dead called themselves, and still do, Deadheads. Any idea of when that took off and why?

Jim Newton: I think it's a derivation of Acid Tests, frankly. It's grown to mean those most loyal fans of the Grateful Dead. In some ways, you can think of the Dead fan base as concentric circles. There's an inner circle of real family, the literal family members of the Dead. Then the next circle after that would be Deadheads. People who toured with the band, who saw dozens of shows, sometimes hundreds or even thousands of shows. It's really fairly extraordinary.

Then, beyond that, a larger, committed, loyal fan base of folks who saw shows when they were in town but maybe didn't travel with the band. I would consider myself in that circle of fandom, but there are many depths to it. One of my favorite quotes is from Bill Walton, the great basketball star, who wrote in his memoir that he had been to 900 or some shows, and an interviewer late in life said, "Really? How many shows did you go to?" His answer was, "Not enough."

Amina Srna: Jim, Actually, I think I just got fact-checked by maybe somebody who has not identified themselves as a Deadhead, but says, please don't call Jerry Garcia a frontman. That totally betrays the ensemble ethic of the band. I think that'll get into the politics. Do you want to just set the record straight here?

Jim Newton: Your listener is certainly correct that Garcia did not see himself that way. I think it's also fair to say that most people outside the band did see them that way. Both things are true.

Amina Srna: You're too kind. You write that Garcia and the Dead were, "At the edges of the. The nation's politics for decades. As they were coming up in the Haight-Ashbury neighborhood of San Francisco, a conservative figure was getting his start in American politics, Ronald Reagan. Can you take us back to the tension of that moment as you see it?

Jim Newton: 1965, '66, as noted, the Dead were really just getting started. They had been playing as the Warlocks. They changed their name to the Grateful Dead. They were performing at the Acid Test, and they were living a value set that included freedom, very much experimentation, both musically and in their lives. Meanwhile, Reagan was running for governor of California. Of course, it was his first entree into politics. Was a fairly well-known actor and politically active, but becoming really involved in electoral politics.

Part of what fascinated m,e and going back through the history, is he too is talking about freedom in that race. Intriguingly, you have the Dead and Ronald Reagan both in California circling each other, talking about and living sets of values that are overlapping in some ways, but meaning very, very different things by that.

Amina Srna: You write about how Garcia admired, "Those who lived beyond the government's authority, the Black Panthers and the Hell's Angels, to name two. What was his relationship to those two groups in particular? What do you think he admired about them?

Jim Newton: Well, I'll start with the fact that there are not too many people who admire both the Hell's Angels and the Black Panther. Jerry would be in a very small group there. I think what he saw in both of those groups was the self contained organizational sense of them, that they were real communities, like-minded people in communities. With the Panthers, he was not so admiring of their revolutionary rhetoric, but more admiring of their community building, the food giveaways, clothing giveaways, efforts to really work in communities.

With the Angels, there's a part of the Dead and a part of Garcia that admired the outlaw feel of that, that sense of living outside the law. I should note, too that Garcia's experience with the Angels was the San Francisco Hell's Angels, which was a much kinder, gentler version of the Hell's Angels even than existed in the East Bay in California. The violence that we properly associate with the Hell's Angels was a little bit diminished in his contact with them.

Amina Srna: In 1988, Garcia was asked about his political views in a long lost interview on KPIX in San Francisco that was resurfaced maybe 10 years ago, I think. Let's take a listen to about a minute of his reply.

Jerry Garcia: We've always really avoided expressing any particular message with our music. We've made an effort to make it as ambiguous as possible so that people could create their own sense. If we're standing for something, we hope that the whole gesture says it rather than the individual songs, you know what I mean? Our songs have purposely not been focused in a topical sense.

However, in the last year or so or few years, we've got a few tunes that you could describe as topical in a way. It doesn't seem to hurt anything. A good song is still a good song. That's the way I feel about it. If a good song talks about something that is current, that isn't necessarily a bad thing, although I personally have sort of fought that for a long time.

Amina Srna: Jim, that ambiguity Garcia is talking about has drawn fans from very different ends of the political spectrum. We actually have a caller who wants to make that point a little bit further. Hi, Michael, Michael in Coney Island I should say, you're on WNYC.

Michael: Hi. Yeah, when I was in college, I was friends with a lot of Deadheads. I was very into the music, but not a Deadhead. I was very into Springsteen, which they weren't, but I liked the Deadheads socially. I felt more at home with them than with Springsteen-head. My question, a couple of my friends, my Deadhead friends, wound up being very right-wing politically. Socially, they were very progressive, and they loved artists who were very progressive politically, but politically, they were right-wing and loved Reagan and continue to be that way. It always confounded me.

Amina Srna: Interesting. Thank you so much for your call, Michael. We really appreciate it. In my research for this, although I think it's well known, conservative political pundits like Ann Coulter and Tucker Carlson are Deadheads. I read Ann Coulter has gone to 67 Dead shows. Jim, what do you make of the fact that the Dead draws a fan base from all parts of the political spectrum?

Jim Newton: Well, I guess I would start by saying nobody controls liking the music. Anyone's entitled to like the music and should. I think there is a libertarian streak in the music and in the culture. As I noted, the outlawness of it is appealing. There may be a way in which that connects up with individualism and conservatism and skepticism of government, all of which are central to conservative values.

I do think it's a more uncomfortable fit politically in the sense that other real values of the Dead and the Dead community are kindness and compassion and community, and a sense of working together. I think some of those can run counter to at least the harder edge conservatism that we see alive in the country today,y and with Reagan, frankly. It doesn't feel, to me, like as easy a mesh as it is with left-wing values, but it's a big tent, and anyone's allowed in. In that sense, if Tucker Carlson or Ann Coulter wants to be a Deadhead, well, I don't get to say no to that. I'm not unhappy not to have run into them at shows, but that's okay.

Amina Srna: Jim, when we spoke yesterday, I said I was willing to bet we would get somebody who has met Jerry Garcia on our air. We have one Carol in Cape Cod. You're on WNYC. Hi, Carol.

Carol: Hi. I'm in Cape Cod, but I'm from Rockaway, New York, and Latham, New York. My cousin, Stephen Parrish, worked for the Grateful Dead from the time he was a teenager. He got us backstage several times at the Knickerbocker Arena in Albany, New York, to meet Jerry. One year we were there, my son was in a wheelchair, and they got him backstage, and Jerry took a picture with him and gave him an autograph, which was not always Jerry's thing. The other thing was, is that Stephen had a tragedy in his family. The Grateful Dead, they were there for him the whole way when you talked about compassion, and it was just an amazing, amazing experience.

Amina Srna: Wow. Thank you so much for sharing. Let's go to maybe one more caller, Poe in Brooklyn. Hi, Poe. You're on WNYC.

Poe: Hey, there. Nice to talk to you. Funny show. I was a kid in the '70s and '80s in San Francisco. I grew up around the Dead and many other bands. I hung out with, Rock Scully, their manager's kids, Acacia and Orianna, Jerry's son, all of that. Went to the studios with my friends, and they handed us joints when we were 12 years old, and it was a bit untended. Sorry, my dog is just walking.

Amina Srna: We're just running out of time in the segment.

Poe: Oh, sorry. I find it interesting that there's so much projection about their politics because it was-- It was very surprising to me, although I did go to many Dead shows as a college student, it was surprising to me that that grew into this nationwide movement. I just want to reframe a little bit from the experience of somebody who was actually there that there was an unbridled narcissism and a lack of concerted politics that many people might attribute to that movement. I just would love to say that.

Amina Srna: Thank you so much, Poe. That actually goes to something that you wrote about in your op-ed for The New York Times recently. Jim. Garcia was a famous musician, and he later on became a billionaire, but you write, "For many people struggling today to find a place between active resistance and doleful compliance, Garcia's life suggests an alternative." I'm not sure if Poe would say that's narcissism, but what would you say?

Jim Newton: First of all, I don't think he was ever a billionaire, but he certainly was a millionaire. He certainly did well.

Amina Srna: Oh, I'm sorry. I misspoke. I meant a millionaire.

Jim Newton: That's okay. I think we're in the habit of saying billionaire these days. Yes, I think he came to believe that the government really didn't meaningfully affect much of his life. I don't want to exaggerate that in the sense that, of course, the government has impact on all of our lives, but I think what he's driving at there is that the things that mattered most to him, his creativity, his freedom, his musical ambitions and exploration, are beyond the reach of government. The government can't control our ideas.

I'm not suggesting that as a plan of action. I was trying in the piece to describe that, but I think that he's onto something there, too, which is to recognize that freedom is not something that the government gives us. Freedom is something that we have, and the government sometimes tries to constrain it, and it is entirely appropriate for us to resist that. That's what he's getting at there, I think.

Amina Srna: That's where we'll leave it for today. My guest has been Jim Newton, editor of Blueprint Magazine at UCLA, where he teaches communication studies and public policy. He's the author of the new book Here Beside the Rising Tide: Jerry Garcia, the Grateful Dead, and an American Awakening. Thanks so much for coming on, Jim.

Jim Newton: It's such a pleasure. Thank you very much for having me.

Amina Srna: The Brian Lehrer Show's amazing producers are my colleagues, Lisa Allison, Mary Croke, Carl Boisrond, and Esperanza Rosenbaum. Our interns this summer are Vito Emanuel and Adelina Romeo. Megan Ryan is the head of Live Radio. Shaina Settingstock and Milton Reese are at the audio controls.

Copyright © 2025 New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.

New York Public Radio transcripts are created on a rush deadline, often by contractors. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of New York Public Radio’s programming is the audio record.