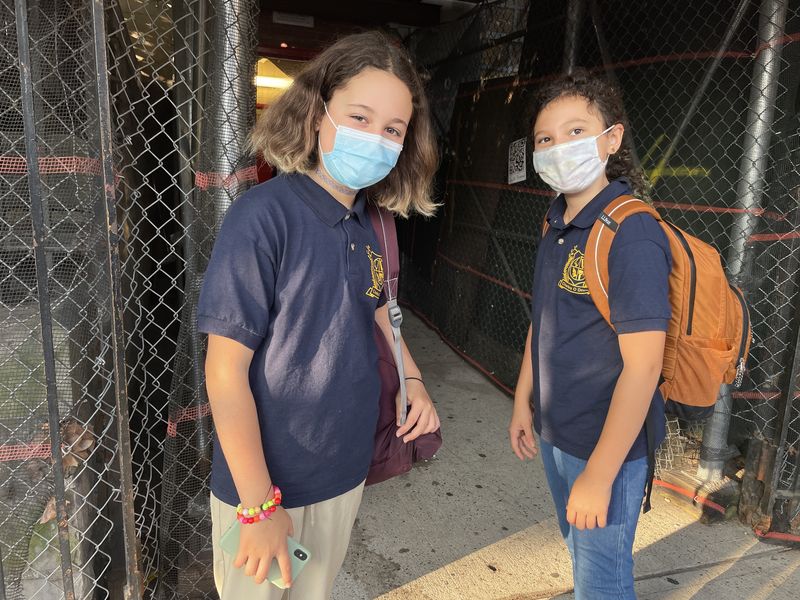

Pandemic Kindergarteners Are Now Middle Schoolers

( Amy Pearl / WNYC )

[MUSIC]

Brian Lehrer: Brian Lehrer on WNYC. For our last 15 minutes today, we're going to have a first day of school in New York City call-in. I know the first day of school elsewhere in the area already happened, but today's the first day of school in New York City. This is for parents of students anywhere because it's been five years since COVID-19 shuttered school buildings and moved children into remote learning.

Of course, it was five years ago this spring, but this week begins, you might say, the 5th or 6th, 2020, '21, '22, '23, '24, '25, school year since remote learning began. We want to know, do you think the pandemic era has had a lasting effect on your child's education, socialization, or personality to this day? 212-433-WNYC. This can pertain to children of various ages, right? 212-433-9692, call or text to say if you think pandemic-era remote learning has had a lasting effect on your child's education, socialization, or personality to this day.

If so, how? 212-433-WNYC. Parents and if any educators are listening right now, you can call, too, and talk about how you've seen it in your students, even though if they're not your actual kids. 212-433-9692, call or text. If your kids were in 3K or preschool in 2020, in March, they're likely entering fourth grade today. Anybody in that particular cohort want to call in? Children who are in kindergarten are entering middle school now, right? Those who are in fifth grade are now entering their junior year of high school, if we've done the math right.

The kids who had just started middle school are now seniors in high school. Students who had just begun high school are likely well out of high school, working or in college. Every year of school is formative for a child. What grade was your child in when the pandemic began? Where are they now in their education, and how did pandemic-era remote learning affect them in the long term, their education, their socialization, or personality to this day? 212-433-WNYC. For worse or in any case, out there, was it for better? 212-433-9692.

Certainly, there have been plenty of reports that school refusal, absenteeism, has been an ongoing issue since kids got used to being at home, at least for some. A 2024 report from the New York State Comptroller's Office found that one in three students in the state were chronically absent, one in three, in the 2022-23 school year. What about your kids' grades, test scores or, more broadly, their ability to read, write, and do math at their grade level?

According to last year's NAEP, the National Assessment of Educational Progress, 33%, a third of eighth graders, had below basic reading skills. That's national, and that was the largest percentage recorded in the exam's 30-year history. Have your kids made friends less or differently in the post-pandemic era, post-remote learning era? We could go on to aspects of individual personality, but you get the question here.

As school is beginning five years after the remote learning era was at its height, where is your child now? What lasting effects of the remote learning era have there been to this day on your child in terms of education, in terms of socialization, in terms of personality? What do you want to report, and how can it help others? 212-433-WNYC, call or text, 212-433-9692. We'll hear from you right after this.

[MUSIC]

Brian Lehrer: Brian Lehrer on WNYC. Okay, let's go up the age ladder a little bit on this. First, I'm going to read a text from a listener who wrote, "My pandemic baby was born in December 2019, one week after the official declaration of the COVID virus as an epidemic. He entered kindergarten this year. We are really interested to see how his age cohort develops academically, as he and many of his classmates seem to have high language and emotional skills. He's never experienced remote learning." Caroline in Montclair, you're on WNYC. Hi, Caroline.

Caroline: Hi, Brian. I was just calling because my oldest child of three was in the first grade, March of his first-grade year, when the pandemic started, and our schools here closed down. Before the pandemic-- and it's hard to say. It was my first kid. Maybe he was naturally going to be more introverted, but he was the kid who would invite everyone to the birthday parties and was a very easygoing, social kid.

Then Montclair was out of school longer than most districts. He didn't really go back until third grade. That first year, we were expecting a lot of transition. Now, he has just started seventh grade this morning. He's a great kid, super smart, but that introversion, that preference to be alone or with books, not necessarily difficulty socializing, but loss of interest has stuck with us. His two younger siblings experienced much, much less of that, who were much younger when the pandemic started.

Brian Lehrer: You were able to see a change from a gregarious kid to one who's more introverted.

Caroline: Yes, his comfort level with saying, "I'll have these kids come over," or "Let's have a birthday party with a lot of kids," that vanished after he spent the good part of a year mostly alone.

Brian Lehrer: Interesting. Caroline, thank you very much for your call. It's funny how you would think it could go either way. I'm sure there are patterns that parents and experts know, but you could be just bursting to get back into a social context, or you could become more introverted as the story we just heard. Listener writes, "I have two teens now. They were in fifth and sixth. Immediately after, their socialization was hit. Older took it worse, had to be moved three times due to refusal, falling into a wrong crowd, just couldn't be accepted to the regular groups due to her bluntness, and went with the rude group." This parent writes, "Even now, as she goes into senior year and doing college stuff, she's hesitant to talk in person. Vastly different," via text. Christina in Lower Manhattan, you're on WNYC. Hi, Christina.

Christina: Hi, Brian. Yes, so my son was in fifth grade when the pandemic hit, and my daughter was in seventh grade. Both of them were impacted really negatively by remote learning, specifically with social skills. This year, my daughter just went off to her freshman year at BU, and she's actually doing really well. I think part of it is being forced to be out of her dorm and meet all of her new classmates.

My son is starting his first day of 11th grade at the Museum School, where they have implemented bell-to-bell cellphone ban, which I think will be fabulous for their social skills because I still see my kids home at six o'clock at night on a Friday rather than being out like they should be. I'm hoping that this cellphone ban will really force the kids to interact and get back to the social interactions that they should have.

Brian Lehrer: Christina, thank you so much for your story. Here's kind of an opposite one to the first caller in terms of valuing interaction and things in real life as opposed to retreating. Listener writes, "My son was a senior in high school five years ago, missed graduation, et cetera. He seems to have an added sense of value for, in real life, community. Lives a little like it's 1972 now in his world. Plays music with others on porches, goes to community dancing every week, and has chosen a social job." Brittany in Templeton, New Jersey, you're on WNYC. Hi, Brittany.

Brittany: Hi, Brian. How are you?

Brian Lehrer: Good. What you got?

Brittany: I teach college freshmen both at a community college and a four-year institution. Honestly, I'm super concerned, just both socially and academically with what's going on with the kids. This year, for example, they must have been in middle school when the pandemic happened. I see them struggling to make friends. They are really uncomfortable interacting with each other. They get very squirmish, more so than I remember feeling when I was in college.

I made tons of friends in my classes at school. I just don't see them making connections the way they used to. That's a huge concern for me. Then academically, just the technology conversation could go on forever as far as artificial intelligence. They really are lacking critical thinking. That's actually the subject that I teach at one of my schools. They really don't like to get uncomfortable and see where they can go in that discomfort. That, to me, is very concerning.

Brian Lehrer: I guess what's hard maybe to separate out is the impact of the growth of screens in and of itself, and now AI, as opposed to the effects of remote learning for whatever period of time, how it interacted with technology. Do you have any sense of that, even informally, just from your individual experience teaching college freshmen?

Brittany: Seeing their addiction to technology is a huge part of what I think is causing problems in both categories, socially and academically. They, first of all, are just so incredibly addicted. Now, we know the science behind that. They are truly addicted to their phones. When I tell them that I have a no-phone classroom, some of their faces just absolutely fall. Then, of course, I have to have the conversation eventually with at least a few of them, "Put your phone away. Put your phone on silent." Then, beyond that, when there's quiet time, we used to turn to each other and chat in class.

If I'm busy doing something, they pull out their phones and start scrolling the second they have a moment of free time. I think the time behind the screens, remote learning, nobody was checking on them. It was easy to scroll off to the side if they're not sitting in a classroom with a teacher looking at them, holding them accountable. The accountability was just not there, and that's another problem. Honestly, there are so many facets to this issue. It's crazy, but I do my part. I do my part with my teaching, critical thinking. I really try to hammer the importance of that into them.

Brian Lehrer: Brittany, thank you for that work, and thank you for saying it on the show. We can get one more in here. Sharon in Brooklyn, we've got about 30 seconds for you. Hi. Can you do it in 30 seconds?

Sharon: Yes, I am the grandmother of a baby that was in preschool behind the screen. Now, she's in third grade. What we did was we pushed all the Girl Scouts, dance lessons, church, play dates, so she can come from behind the screen and make socialization. I also just tell parents, "Watch what your kids do on those devices. They're the devil."

Brian Lehrer: That ends with the word "devil," and the words "the devil." Sharon, thank you very much. Listeners, thank you all for calling and sharing your experiences, even with all the stress involved. Probably in saying them out loud, maybe it helps others to hear what some of you have gone through yourselves. Thank you for your calls. That's The Brian Lehrer Show for today, produced by Mary Croak, Lisa Allison, Amina Srna, Carl Boisrond, and Esperanza Rosenbaum. Juliana Fonda and Milton Ruiz at the audio controls. Stay tuned for Alison.

[MUSIC]

Copyright © 2025 New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.

New York Public Radio transcripts are created on a rush deadline, often by contractors. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of New York Public Radio’s programming is the audio record.