Betting On Everything

[music]

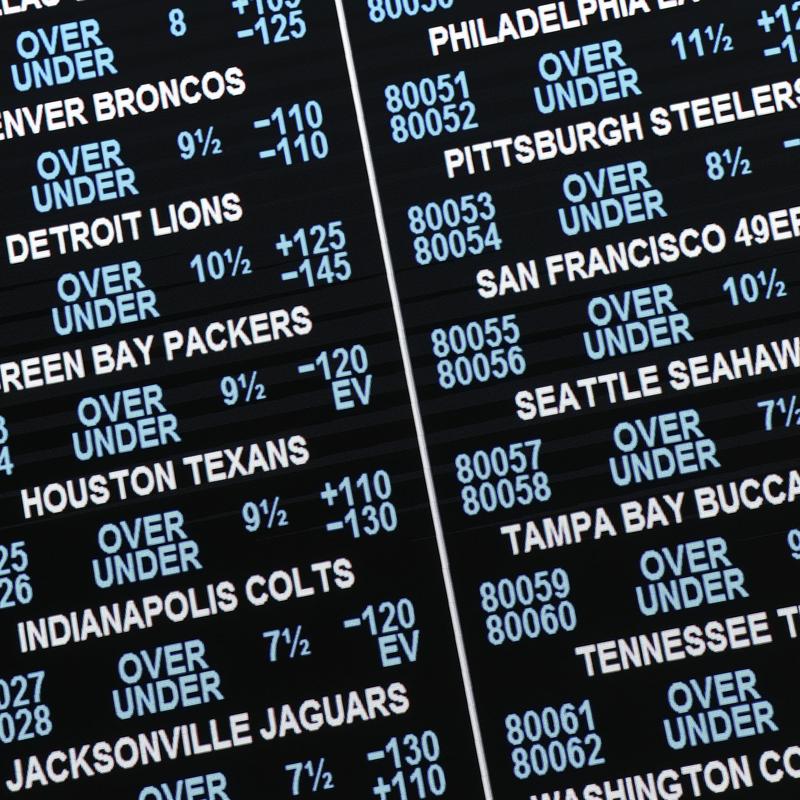

Brian Lehrer: Brian Lehrer on WNYC. There are these things called prediction markets where you can place wagers on anything, from world events to elections to award show outcomes. So much more than just sports. Here's a sampling of things you can currently bet on using one of these platforms, Polymarket. What songs will be played at the Super Bowl halftime show? How many times will Elon Musk tweet between January 9th and January 16th? You might have also noticed this at the Golden Globes on Sunday, a small on-screen pop-up sponsored by another betting platform, Kalshi, showed the odds of each award in real-time, essentially letting viewers track and potentially bet on the winners as the show unfolded.

Then there are political bets. Things like, will Donald Trump acquire Greenland before 2027? Will the Iranian regime fall by January 31st? Who will be the Republican presidential nominee in 2028? Now, sports betting was legalized at the federal level back in 2018, and to be clear, sports bets still make up the largest share of the market, about 90%. These largely unregulated prediction markets have really taken off recently, and their growing popularity introduces a new set of questions, right? Like, how do you determine the outcome of a world event that people may not even agree on?

Or what does insider trading look like in a market that isn't regulated, like the stock market? There was a viral video recently of the White House press secretary, Karoline Leavitt, abruptly ending a press conference after about an hour and four minutes. People online noticed that there had been an active bet on whether she would speak for more than an hour and five minutes. Some speculated it was an inside job, rigged. That's pure speculation, but it gives you a sense of the kinds of situations that this is producing.

Another recent controversy involved a Polymarket bet on whether the US would "invade" Venezuela. When Maduro was ousted by President Trump and executive power was seized and transferred to his vice president, the platform ruled that this did not count as an invasion. Trump, of course, said it was an arrest. These companies aren't just hosting bets, they're effectively acting as arbiters of truth. Now, Jonathan Cohen is a gambling historian and author of Losing Big: America's Reckless Bet on Sports Gambling.

He's been on the show to talk about that, and he's with us now to talk through this emerging market and how the gamification of everything may blur the lines between gambling and investing and could even affect world affairs. Jonathan, thanks for coming on for this. Welcome back to WNYC.

Jonathan Cohen: Thanks. Can we talk about the $25,000 I have bet on the Finnish election this year? Is that okay?

Brian Lehrer: No, no. We're going to keep that a secret so you don't reveal your conflict of interest. FanDuel and the other sports betting apps have been around for a while. Like I said, when did we start to see this gambling industry expansion beyond sports into politics, culture, world events?

Jonathan Cohen: Prediction markets themselves as a product have been around since the '80s and '90s, but they really got their first foothold, let's say, in the US, for the 2016 election through some obscure Australian-run academic program, actually, technically it was. Then it was really during the Biden administration or right around the Biden administration that they took off as mainstream products for betting on things like election outcomes. Then they really took off. It was just at the beginning of 2025 when they began offering sports markets.

It was really the March Madness, the college basketball tournament last year, that they really, really got their foothold and became a mainstream gambling product along the likes of FanDuel, DraftKings.

Brian Lehrer: Listeners, you are very invited in here. Santiago in Brooklyn, we see your call. You're going to be first, Santiago calling already to say he uses prediction markets, and we want to hear from you. Do you use any of these betting platforms for anything other than sports? Folks, you want to tell us the most unlikely, absurd, funny, or maybe disturbingly inappropriate thing you've ever bet on or that someone you know did. 212-433-WNYC. Something other than sports, obviously. 212-433-9692. Have you ever disagreed with how one of these apps determined an outcome?

Or maybe you've noticed on the Robinhood app that it's not only for investing anymore. That's what Robinhood is. Or tracking your IRA. You can also place sports bets or make wagers on world events there. We want to hear your stories, your opinions, your questions. 212-433-WNYC. 433-9692, call or text. Santiago in Brooklyn, you're on WNYC. Thank you for calling in. Hi.

Santiago: Hi. Thanks for having me. I'm a user of one of these apps, Kalshi, which is one of the two big ones, and may sound hypocritical, but I saw this, and I felt so compelled as well because they feel so bad for society in kind of a way that's similar to sports betting. They've infiltrated everything. If you watched the Golden Globes, they were playing Polymarket in the cuts between commercials, they were playing the predictions for the awards, and it just felt so toxic. One of the things I have-- comment that I think is interesting is this idea that these are these more accurate ways of finding out what's going to happen in world events, which I thought was funny.

I'll give you an example related to New York, the mayoral election for the longest time, until I think it might have been late May, it was showing that Andrew Cuomo was like 80% chance he was going to be mayor. I know he was still leading the poll, the whole thing but there was this seemed like this giant lack of understanding and underpriced. Zohran Mamdani was at maybe 7%. I bet on Zohran Mamdani because I thought he had a better chance, and it turned out great for me. All that, but it missed this huge, very obvious thing happening.

I think one of the last thing I'll add is seeing how much this industry is now gaining steam and political influence. I saw this morning that Sean Patrick Maloney, the former congressman from New York, he was just named the head of this business organization that represents the production markets. It seems like they're getting into lobbying now. I would go into the insider trading part later, but I think it's interesting that, for example, if you want to trade on stocks, you have to register, you have to verify your identification. There's a record with the SEC of who makes these trades.

If you want to make a Polymarket account, you just set up a VPN and pretend like you're in France, and then you can just connect a crypto wallet. You don't have to put an ID in, so you can make bets on this stuff if you're like an insider trader or something like that. Those are my comments here.

Brian Lehrer: Thank you very much. A lot of insight there, Santiago. Thank you very much. Jonathan, anything you want to say to that call, and articulate for the listeners what you think the harm is of this? Some might think, "Okay, if I want to bet on Mamdani vs Cuomo in the election or whether there's going to be regime change in Iran, it may be weird in a certain way, but nobody gets hurt." Does anybody get hurt?

Jonathan Cohen: I don't want to be prudish because, like you said, I think gambling can be fun and it's a fun human pastime where I see people getting hurt are a few ways. First is you already outlined that these are lightly regulated, especially compared to sportsbooks and formal sports gambling. At least on paper, FanDuel and DraftKings have to care about whether you lose your shirt, and whether you run out of money, and whether you get addicted to gambling. Whether they actually care, we can talk about, but they at least have to pretend to care.

Kalshi and Polymarket don't even have to pretend. They have basically no gambling addiction protections. There are all these Twitter accounts that showcase all these users who are losing all sorts of money because everything is public and every user's trades is public. Not only do you not have these consumer protections that you do have on some of these sportsbooks, at least to a degree, you also have what you already alluded to, this sort of the gamblification. Like, are we sure we want to be advertising during the Golden Globes that you can gamble on the Golden Globes?

I'm okay with gambling in general, but should we really be forcing it down people's throat and making everyone see every interaction or every news event as a way to make money and as something that they can leverage predictive ability on? I think that to me is going a bit too far. Not to mention the fact that it's happening on Robinhood, and the same app that you use to manage your 401(k), you can use to bet on the Eagles. Not anymore, but you can bet on the Texans.

Brian Lehrer: [chuckles] Anderson in White Plains has an international example of where he thinks this kind of thing is having a severe negative effect already. Anderson, you're on WNYC. Hello.

Anderson: Yes, hi. I'm from Brazil. I live in New York, but in Brazil, as most people know, soccer is such an important part of the culture. It's so, so important, but unfortunately, the past five years was being affected because the betting websites, which are mostly from the United States and some from Europe, they are so strong there, they lobby politicians in order to get a free range of how they operate. These betting websites, they advertise on the big teams' uniforms and on TV, the screen, you constantly get bombarded with their names, and celebrities are also paid to advertise.

Brian Lehrer: That's still sports betting, but what do you think the negative impact is that you called to describe?

Anderson: The negative impact that I see is people really not enjoying the sport anymore as they used to. Like I was used to watch with friends, and people are constantly on their phones looking of as the game is going, "How should I bet? How should I place a bet?" It's taken away from the enjoyment of the soccer and getting together with your friends and enjoying something so important to the culture. Also, a lot of families are having enormous impact because some fathers, some mothers are losing everything because they keep trying to recuperate what they lost, and they never do.

Brian Lehrer: Anderson, thank you for your call. We appreciate it. Jonathan, I want to come back to the Karoline Leavitt example that I used in the intro. These press conference rumors that she ended this particular news conference at an hour and four minutes, maybe because she knew there was a betting market where the over-under was at an hour and five minutes. Those rumors weren't confirmed, but they introduced the idea that this kind of thing is possible, that officials could bet on events they're involved in.

If you work in the State Department or have access to classified information in any way, what's stopping you from betting on a world event before it becomes public, and then maybe even trying to bring about that outcome, even if it's bad for the country or bad for the world? That strikes me as one of the worst-case scenarios here.

Jonathan Cohen: Just to be clear, there's no evidence that Karoline Leavitt actually did bet any money. I think it was $250 or something that was bet that she would end below 65 minutes. The fact that you might even think that she's doing it because of the prediction market,-

Brian Lehrer: Whoops, did we lose, Jonathan?

Jonathan Cohen: -it's sort of-

Brian Lehrer: Oh, you're back.

Jonathan Cohen: -[crosstalk] itself. Trust in institutions is, of course, in such high supply in American society these days that now we have just this other vector of people to distrust and to feel that things are rigged, let's say, in their favor. On the insider trading question, on paper, insider trading should be a asset. Part of the point of a prediction market is if you have better information than the public, you should be able to leverage that because if a prediction market is in fact a source of truth and a way to assess the wisdom of the crowds, then let all the every member of the crowd, including those with insider information, leverage that information.

Because these companies want to be legitimate and they want to be seen as legitimate financial instruments, not just gambling products, they have to say that insider trading is not allowed. Whether or not they do anything about it is a separate question, but they have to claim that insider trading is not allowed, that you can't invade Venezuela, or you can't bet $400,000 on the invasion of Venezuela and then go about and actually invade Venezuela.

Brian Lehrer: Are there any confirmed cases of government insiders actually profiting off prediction markets by then making policy that conforms, or are we still in a warning sign stage?

Jonathan Cohen: I think warning sign. We have indications that these are still under investigation, not about government actors, but of people with insider information. There was a huge amount bet on Aaron Judge to win the American League MVP right before it was announced. There was a huge amount bet on actually the awarding of the Nobel Peace Prize to the Venezuelan activist right before it was announced publicly. There seem to be these cases where people are leveraging inside information, but again, what these companies are going to do about it, I don't know.

Brian Lehrer: You report that the president's son, Donald Trump Jr., has become a paid strategic advisor to the prediction market Kalshi, which is, as we've said, one of the biggest players. How unusual is that level of family involvement, president's family, in an industry that's supposed to be regulated by the federal government?

Jonathan Cohen: That's right. I can't tell if this is a normal Washington scuzzy business stuff, where you appoint the President's son or the AG's nephew or whatever to be on your board just to give them a glorified position. Just to be clear, he's also a strategic advisor with Polymarket, which is Kalshi's competitor. I can't tell if this is real and a way to protect the industry or if this is just typical Washington stuff. I certainly think it basically draws a red line. I've talked to lobbyists who are working on this issue and who have proposed or are working on legislation to restrict and limit prediction markets.

They basically see it as a total no-go and that there's no way you're going to get Republicans in Congress to support such a legislation because they know that the President ultimately will not support the legislation.

Brian Lehrer: I see that Congressman Ritchie Torres from the Bronx is one of those who has introduced legislation in this realm, but why would it break down along partisan lines?

Jonathan Cohen: In this case, it might break down purely because the Republicans have been forced into being pro-prediction market because Donald Trump Jr. has now invested in prediction markets. I do think nominally it shouldn't break down on partisan lines. The anti-gambling chorus in Congress actually cuts both ways in very interesting ways. Prediction markets, because of their connections to politics, seem to be, and both connections to politics, I mean, in terms of both the investment by the Trump family, but also because they actually, as you've alluded to, the fact that you can bet on political outcomes seems to be perpendicular to the sports gambling conversation.

The sports gambling conversation that crosses red-blue in all sorts of interesting ways, but the prediction markets, it might not work out that way.

Brian Lehrer: Let's see. What should I do with our last minute? I guess I'm going to ask you about if one wanted to bet that Marco Rubio is going to be the Republican presidential candidate in 2028, to take that hypothetical, would I have to wait until 2028 to see the returns on that bet? Or can people cash out before then, based on how the odds change over time? Does it get that granular and maybe addictive in that respect?

Jonathan Cohen: Yes, it's absolutely that granular. This is why you have people who are on these sites and are using them every minute and every day. They claim that they can't sleep because they don't want to miss an odds change. This is not like you're betting on the Bears and you have to wait three hours until the Bears game is over, and then you either win or lose your bet. The odds of Marco Rubio being the presidential nominee are 20% but you think they're going to go up, and so you buy them at 20%.

Then he announces his campaign, for example, the odds go up to 40%, and you can cash out at a 20-cent profit per share. That's the point of prediction markets, it's not you're actually trying to predict what happens, it's you're trying to predict what other people think is going to happen, and whether you can make money to that effect.

Brian Lehrer: That is where we have to leave it with Jonathan Cohen, gambling historian, author of the book Losing Big: America's Reckless Bet on Sports Gambling. Jonathan, thanks a lot.

Jonathan Cohen: Thank you.

Brian Lehrer: Brian Lehrer on WNYC. Thanks for your ears. Thanks for your calls and texts. Stay tuned for all of it.

Announcer: This is WNYC FM HD and AM New York.

Copyright © 2026 New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.

New York Public Radio transcripts are created on a rush deadline, often by contractors. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of New York Public Radio’s programming is the audio record.