30 Issues in 30 Days: Rikers Island

Title: 30 Issues in 30 Days: Rikers Island

[MUSIC]

Brian Lehrer: It's The Brian Lehrer Show on WNYC. Good morning, everyone. On today's show, Graham Wood from The Atlantic, who writes about the Middle East on reasons for both concern and paradoxical optimism, as he quotes a well-known Palestinian saying to him on what comes next for Israelis and Palestinians. We'll look at the layoffs and then unlayoffs at the Centers for Disease Control the last few days, with a focus particularly on their publication, that's the main source of data in the United States on what makes people ill or kills them in this country. Does the Trump administration, after having at least temporarily laid off most of the staff from that publication, really not want to keep track of that?

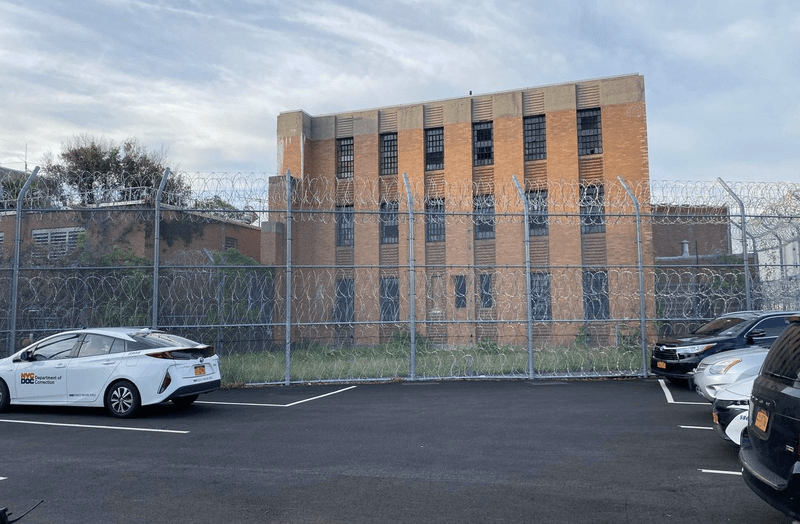

We begin with our 30 Issues in 30 Days election series. Issue 17 today, closing Rikers Island or not closing Rikers Island as an emerging issue in the New York City mayoral race. Closing it by 2027, if you don't know, is the law, but Curtis Sliwa has always said keep it open. Now, Andrew Cuomo wants to keep a jail there, too. We'll hear clips of all three candidates' arguments, but here's the one that made news first. It's Cuomo last Wednesday.

Andrew Cuomo: We should rebuild new state-of-the-art jails on Rikers Island, provide free bus service, and use those existing sites for housing and commercial development.

Brian Lehrer: Cuomo last week calling to scrap the construction of four borough-based jails, one in each borough except Staten Island, is the plan. Use those sites for housing and build a new jail on Rikers Island instead. We'll hear more from Cuomo, plus Mamdani and Sliwa as we go. We'll do this 30 Issues segment a little differently from our other recent ones. We've been mostly having explainers or debates. This is going to be kind of an oral history and point of view by our guest, who was part of the de Blasio administration when the close Rikers plan was created. Our guest is Elizabeth Glazer. She is the founder of the New York City policy journal, Vital City, which is a quarterly and has a think tank associated with it.

She's been on the show a number of times. In that context, the last couple of years. She previously served, though, as the justice advisor to Mayor de Blasio. She was also the New York State deputy secretary for public safety, state deputy secretary when Andrew Cuomo was governor. She's got a foot in both of those camps, and she still supports closing Rikers, probably most in line with Zohran Mamdani's current position, but just wanted to say there are all those connections of hers for full disclosure, in addition to her having been a federal prosecutor. Liz, thanks for coming on for this. Welcome back to WNYC.

Elizabeth Glazer: Thanks so much, Brian. Glad to be here.

Brian Lehrer: I said this would be part oral history, so tell everybody where the idea to close Rikers first came from and how it got considered and processed by you and Mayor de Blasio as something to take seriously.

Elizabeth Glazer: Sure. I don't think that there's been a time since Rikers has been open when it hasn't been in trouble. It's really hard to remember when it hasn't been under a consent decree and when conditions haven't been terrible. One of the first things that de Blasio and me and my team did when we first came in is to try and understand why things were so terrible. In that very first year, the city actually agreed to enter into a consent decree with the federal government. The US Attorney had been investigating Rikers and had determined that violence was so out of control that it reached unconstitutional levels, and put in what's called a monitor to make sure that that would be fixed.

One of the first things that we did was really look at the population and figure out how many people really need to be in Rikers, and is the population, which is often a driver of violence, the size of the population, is there a way to reduce that, consistent with public safety? That was an enormous effort. Then there was a big focus on--

Brian Lehrer: Can I jump right in there for one little note?

Elizabeth Glazer: Yes, for sure.

Brian Lehrer: From what you just said, it means that the plan to close Rikers and improve conditions for people incarcerated in New York City must have intersected with the bail reform movement, because you're talking about jailing-

Elizabeth Glazer: Very much so.

Brian Lehrer: -fewer people in the first place before their trials.

Elizabeth Glazer: Very much so.

Brian Lehrer: Bail reform, which is its own controversy at its own issue in this 30 Issues segment, was part of the plan to close Rikers.

Elizabeth Glazer: Well, I would say, bail reform makes it seem like it's just about the law, which was obviously very important, but really, the central question was who needs to be in and who doesn't? We're pretty careless with liberty. People stay in when they have very low bail amounts. They get out when they have very high bail amounts. One of the first things, in fact, in the first six months that we did was to give judges some option between putting somebody in and letting them go with nothing. This was the Supervised Release Program, which became very popular with judges and has now grown quite a bit.

Again, it's a way to think about how to have the most safety with the lightest touch. Yes, very much population control, controlling the number of people at Rikers is about how many people go in, and that has partly to do with figuring out options aside from jail, but also, critically, and this is what's so important today, is how long they stay. The amount of time that people are staying has been rising, rising, rising, rising. That's one of the reasons--

Brian Lehrer: In other words, the length of time between arrest and trial?

Elizabeth Glazer: The length of time between the time the judge puts you in and when your case is finally resolved, whether you plead or you go to trial. That has just risen astronomically. Important here is that jails are different from prisons. Jails are largely for people who have not yet been convicted of a crime, and they're held pending the disposition of their case. These are not, for the most part, sentenced prisoners. It's supposed to be people who are there for a relatively short period of time, but when you look at these numbers, about a quarter of the population has been there for more than a year. Maybe a third of those--

Brian Lehrer: Why? Not enough-- yes, maybe a third of those. I'm sorry, go ahead.

Elizabeth Glazer: No, maybe a third of those, two or more years.

Brian Lehrer: Wow. Is that because not enough judges, or why would that length of time have been expanding on average?

Elizabeth Glazer: Everyone has a piece of this, right? Is corrections able to get people to court on time? Literally, something that mechanical and simple. Does the judge know that the defendant is there and call them up to court? Has the defense lawyer met with the person in advance so that they're ready to have a meaningful court appearance, so it doesn't get put over for a couple of months? Although everybody has a role, one of the central drivers has to be the courts to organize and to move along cases consistent with fairness. That has been an enormous effort, and it's been a focus of the Chief Judge Lippman when he was there, of Chief Judge DiFiore when she was there, of the Chief Judge now. It's just been enormously difficult to move.

Brian Lehrer: It seems so ironic to me, just from my understanding of what happened over those particular years that you're referring to, almost the entire length of the de Blasio administration, from 2014, when he started as mayor, through at least the beginning of 2020, crime had been going down in New York City. I imagine, for you as criminal justice policy advisor there, you were seeing fewer arrests, and yet the length of time being incarcerated at Rikers before a plea or a trial, finished the case, was expanding for people. It's hard for me to make sense of.

Elizabeth Glazer: Yes, this has been a particular problem in the past couple of years. 2017 to 2019 were just about the lowest crime stats on record in New York City, and it was accompanied by the lowest rate of incarceration since the city has been keeping track of that. The reason for that were a whole bunch of different things, but one of them was this effort on the part of the cops, with respect to arrests, DAs, the court system, others, to really have the lightest touch possible. When de Blasio came in, there were about 11,500 people in jail. By March of 2020, when there was really a focused effort to shrink the jail population consistent with safety, the population dropped to about 3,800.

To me, that was a signal of what happens when really, there's coordination and focus with urgency about who really should be in jail and for how long.

Brian Lehrer: That decline in the Rikers population gave you more hope that closing the jail and starting anew with four other locations around the city that might have better conditions for everybody, both the people incarcerated there and the corrections officers, might be possible, but then crime did start to go up in 2020, and Mayor Adams had his own policies. Do you know the rough number of people at Rikers right now?

Elizabeth Glazer: About 7,000.

Brian Lehrer: Oh, so it pretty much doubled.

Elizabeth Glazer: It's up about 800 from last year. It's been consistently rising since he's taken office--

Brian Lehrer: Which is going to make it more difficult to find enough cells to disperse that population, assuming that rate continues, and we'll get to that.

Elizabeth Glazer: Again, so important to focus, it's not just how many people go in, because that hasn't really risen that much. The problem has been how long they stay. That's where the focus, I think, needs to be. The average length of, say, for people who are staying more than a month was about 165 days in 2019. It's now 227 days this year.

Brian Lehrer: Listeners, if you're just joining us, we are in our 30 Issues in 30 Days election series here on The Brian Lehrer Show. Day 17, Issue 17, closing Rikers Island or not, as an emerging issue in the New York City mayoral race. Closing it by 2027 is the law, but Curtis Sliwa has always said keep it open. Now, as of last week, Andrew Cuomo wants to keep a jail there, too. We're doing this 30 Issues segment as an oral history and point of view by our guest, who was part of the de Blasio administration when they crafted the close Rikers plan. Elizabeth Glazer, these days, founder of the New York City policy journal, Vital City, but she was justice advisor to Mayor de Blasio.

She also served under Andrew Cuomo when Cuomo was governor, so she's got a foot in both of those camps, as I said at the top of the hour. Her own views are probably most in line with Zohran Mamdani's on Rikers Island. Listeners, we invite your questions, comments, or stories. 212-433-WNYC, 212-433-9692. Continuing with this oral history approach--

Elizabeth Glazer: Brian, could I just interject very quickly?

Brian Lehrer: Sure. Go ahead.

Elizabeth Glazer: We were working hard on this issue, but really, I think what the galvanizing force was in getting the mayor to say that he would close Rikers, in motivating then Speaker Mark-Viverito to create a commission to study this was this enormous grassroots effort from advocates, particularly people who had been formally incarcerated, who were really kind of tireless up to and including following the mayor to his daily gym workout, but doing all kinds of things to make this issue prominent, something that has been so hard in the jails because more than anything, everything happens behind closed doors.

Brian Lehrer: I think as part of this oral history, and listeners, I hope you're finding this oral history approach to this issue interesting and informative, and thoughtful. We're trying in good faith anyway, as we try to do every day, one way or another. I think we have one of those grassroots organizers from that period of time calling in. Let's see if Darren in Brooklyn wants to contribute to this oral history in a particular way. Darren, you're on WNYC. Thank you for calling.

Darren Mack: Thank you so much for having me. Good evening. My name is Darren Mack, he/him pronouns. And I'm a co-director of Freedom Agenda, which is a member-led grassroots organization working with directly impacted people for decarceration assistance transformation. I wanted to basically speak to your very first question about the origins or the idea of closing Rikers Island. That came from survivors of Rikers Island like myself, family members, loved ones who were detained or lost their lives in Rikers Island, like Akeem Browder, the brother of Kalief Browder.

I remember vividly Kalief Browder, when he was sharing his story, it put a spotlight on what was happening on Rikers Island, and ultimately, he took his own life. Under the radar, organization and partners, and myself have been working to launch the campaign on Rikers Island in 2016. At that same time, the mayor was asked by a journalist that documented about this idea from advocates to close Rikers Island. He said it was a fantasy, but because of our advocacy and our organizing, we moved New Yorkers to understand that Rikers cannot be fixed, Rikers cannot be reformed, and the only solution was closure.

Due to that, we won a legislature to close Rikers Island, and we're going to continue to move whoever's the next mayor to understand that and carry out the plan to close Rikers Island ultimately and remove this stain from our city once and for all.

Brian Lehrer: Darren, you mentioned Kalief Browder, who some of our listeners will remember was a young person who was incarcerated at Rikers Island for a long time before he took his own life. I don't remember the exact length of time, but I know that was part of the story.

Darren Mack: Three years.

Brian Lehrer: Thank you, and charged only, if I remember correctly, with stealing a backpack. How central do you think Kalief Browder's story and the publicity it got at the time was to actually finally having a policy of closing Rikers Island?

Darren Mack: Yes, it was central. Rikers have been out of sight and out of mind of New Yorkers for so long, but his voice, experiencing Rikers Island and the horrors that he suffered, the trauma that caused him to take his own life, put a spotlight on it. Similarly, members of Freedom Agenda and the campaign to close Rikers are continuing to advocate and organize and come up with solutions. We can mitigate some of the harm that's happening now, like ending solitary confinement and decarcerating and getting people off of Rikers Island, as the city should be moving forward with closure. Yes, Kalief Browder's story was definitely pivotal in raising awareness about the horror that was happening on Rikers.

Brian Lehrer: Why do you think, from your point of view, that things will be any better at the four proposed borough jails? Is it not a matter of behavior and policies as opposed to this location versus that location?

Darren Mack: Yes. For long-term New Yorkers, we know that we had borough facilities next to the court for decades, and that's how it is all across the country. The jail is next to the court. We haven't heard stories about the horrors, the brutality and death coming out of the borough facilities when they existed. That's because the accessibility to your families, the accessibility to organize if something is happening in there that we need to raise awareness about accessibility to attorneys. Having a smaller, more humane, accessible, transparent jail facility is the way forward.

It works, but we also need to continue to decarcerate and with more transparency, and to keep the Department of Corrections accountable for what's happening in the borough facilities when we close Rikers Island.

Brian Lehrer: Darren, thank you very much for your call. We really appreciate your contribution. Liz Glazer, back to you. What made you think, to the question that I just asked him, when you were working for Mayor de Blasio, that anything would be better for either those incarcerated in New York City or those corrections officers who work there by moving the locations? He talked about them being right near the court as a key to this, that there aren't the horror stories of how people are treated in places around the country where the jails are next to the courts, where, of course, their lawyers would be, and where they may be going in and out for their own proceedings.

Was that largely it, or what else led you to believe that things would actually be better at these smaller borough jails?

Elizabeth Glazer: I think there were a bunch of things, and I think Darren said it beautifully. The jails are out of sight and out of mind. Just think about this year. There have been 12 deaths in the jails, and I don't think it's on anyone's radar. There's a kind of value to having natural surveillance. You have families going in and visiting. You have lawyers going in and visiting. This issue of court delay that we talked about, that was such a big issue for Kalief Browder, too. Those three years could potentially be shortened when you don't have those same problems in getting people from jail to court, but there's also a question of, physically, what does it look like, and how do people feel, and how do they live there?

The facilities now are crumbling. You burn up in summer, you freeze in the wintertime. They're not designed to have programming and all the kinds of things that would lead to a decent quality of life, but there's something more than it. It's not just that a beautiful building is going to change the conditions of confinement or the real brutality of what happens inside. Something else has to happen at the same time, which is a lot of what this most recent consent decree that's been going on now for 10 years is focusing on, which is you have to change the conditions inside. How officers are trained and supervised, how they treat people who are incarcerated.

What kinds of opportunities people who are incarcerated have for classes and programming and other things is absolutely crucial. Otherwise, all you're going to be doing is moving the same brutal conditions from one building to another.

Brian Lehrer: Before we get back to the mayoral candidates, which is, of course, the context for this segment, because they do take different positions. We'll play clips from all three coming up. Let me take one more call from somebody who says he was incarcerated at Rikers. If we heard from Darren, the first caller, about the campaign to change things and how they want it changed, I think Bryan in Manhattan is going to more describe what some of the conditions are inside that have led people to be so horrified and led to this federal takeover, which is currently the situation.

They don't even let the city run Rikers anymore because of what was documented in court. We may get some oral history that's a personal history from Bryan in Manhattan on that, it looks like. Bryan, you're on WNYC. Thank you for calling in.

Bryan: Thank you. A great show. I'm choking up. I got tears in my eyes just listening to this. Yes, I survived Rikers Island, but I think even the most hardcore Republican, I don't put them all in a fascist camp and just try to pigeonhole. I think most people, if they knew what was actually going on in Rikers Island, they would be horrified. They would be disgusted. I saw people cut their wrists while guards watched. A couple of cells down, somebody hung himself while the guards watched. Matter of fact, I think they ended up arresting and charging guards for watching people. Supervisors watching a prisoner hanging for five minutes, eight minutes. It's horrible. It would shock the conscience.

It made me disillusioned in America more than anything else. I'm no naive kid, but what I saw there and the fact that they put you-- like the first guy, what's his name? Darren, Freedom Agenda, I've seen them guys, and they're good people. He said about out of sight, out of mind. That's what it is. People get sent out there here. If I could say a couple of things, I've been waiting to say this for a long time. Somebody said earlier in the show that when they lowered the Rikers Island population, crime levels went up, but that's not a cause-and-effect.

What people don't realize, they also had parole reform, and so a lot of people got released from prison. A lot of people were on parole, and there's no support system. You can't take something that's been going on for hundreds of years, the structural racism and oppression that's going on here, and then pass a law and say, "Okay, in one year or two years, we're going to do an analysis and see what happens." You can't. That's not fair. It's not even honest. If you think, like in California, in prisons, there's maybe, for every incarcerated person, there's one guard, right? That's the numbers. The--

Brian Lehrer: Ratio.

Bryan: A whole prison might have thousands of people incarcerated, and there's only hundreds of guards. In New York City, there's more employees than prisoners. There's over 7,000 uniformed guards, and there's another 2,000 civilian employees. How is that possible? They're spending over 500--

Brian Lehrer: What's the impact of that ratio in your experience or opinion?

Bryan: It's oppression. The corruption that goes on there, the violence that-- just imagine this. They could take one person out of Rikers Island and put them on an ankle bracelet, and send eight kids to NYU or Columbia for a year. If you do that for 30 years, imagine, you're going to have hundreds and hundreds of people in the community that are now college-educated, that now, instead of growing up in a single-parent home, they have two-parent homes. That's what you need to do to address something as overwhelming as structural racism. In Rikers Island, the mass incarceration, that's the cornerstone of what's wrong.

Last thing I'd like to say, Brian, is it wasn't de Blasio or his administration that pushed to close Rikers. It was survivors and civil rights activists, people that saw what was going on there. When--

Brian Lehrer: Push the government into it.

Bryan: Yes.

Brian Lehrer: Raised awareness.

Bryan: The same thing, pushing the feds, but just imagine a world where instead of locking up people for everything, people that have mental health issues get mental health care, and people who have drug issues have drug care, and that the idea should be, let's send as many kids to school as we can and not jail. I remember Jesse Jackson. People used to scoff. Remember when he used to say, "It costs more to send somebody to jail than it does to Yale." It's never been more true.

Brian Lehrer: Let me leave it there. Thank you for--

Bryan: Oh, man. Anyway, thank you. We have to do something.

Brian Lehrer: Thank you for your contribution to this segment. Liz, so much there. What were you thinking? What would you like to react to from Bryan's call before we get back to the clips of the candidate?

Elizabeth Glazer: Bryan's exactly right. It's not just the level of violence. It is the kind of violence. He was talking about Michael Nieves, who got a razor in the facility, slit his throat in front of the guards, and they watched as he bled out. Another person that he referred to hung himself in front of a captain who was making jokes as he died. Herman Diaz, who choked on an orange because the facility was not staffed appropriately. He's exactly right. It's not a question of money. We spend about $500,000 a year on each person incarcerated. It's not a question of staffing. We have the most richly staffed jail system in the country. It's not a question of oversight. We have many different oversight facilities.

What I'm about to say is going to sound so kind of bloodless in comparison to these horrendous problems, but it is a problem of management and oversight and supervision and accountability, that this is an organization that just doesn't run, and as a result, the kind of horrendous things that the caller just referred to are happening on a too regular basis. It's why I think the federal courts have finally stepped in for what is a very extraordinary remedy, which is a receiver.

Brian Lehrer: If those conditions were that extreme, why was it not in control of the mayor, de Blasio, when you worked for him in that administration, or Adam since to change it?

Elizabeth Glazer: I think it requires more power than even the mayor has, whether it was under us or under Adams. The last corrections commissioner that de Blasio had, Vinny Schiraldi, urged a receivership. There were--

Brian Lehrer: You need federal government or court take over?

Elizabeth Glazer: Right. So that what the court does is appoint somebody who is independent of politics and who can cut through the red tape and all kinds of regulations and other things, meaning that staffing doesn't go right and that accountability doesn't go right. This person essentially really stands in the shoes of the mayor to operate the facility. They are the executive. It will depend very much on who the person is, who's appointed, but this is an issue that even the monitor has now, over the past few years, essentially said the place has to be rebuilt from the ground up.

There used to be, there were, there are 300 more provisions on the consent decree to try and get violence down, violence which is now well above the unconstitutional levels that it was when the decree was entered into. The monitor has said, "You know what, don't even worry about those. Just focus on the four things that matter. Figuring out security, management, supervision, accountability. IE, everything. Rebuild the organization."

Brian Lehrer: When we come back from a break, we'll play clips of the three mayoral candidates on what they would do to address conditions at Rikers, including closing it. You said build from the ground up. That's part of what's new from Andrew Cuomo. When he says no, he no longer supports closing Rikers Island. He is talking about building from the ground up just on that site. We'll hear that clip and more from the other candidates and continue with Liz Glazer. 30 Issues in 30 Days. Issue 17, closing Rikers or not, as an issue in the New York City mayoral race. Stay with us.

[MUSIC]

Brian Lehrer: Brian Lehrer on WNYC. Issue 17 in 30 Issues in 30 Days, our election series, with Elizabeth Glazer, founder of the New York City policy journal, Vital City. In the last few years, she worked for Mayor de Blasio when the close Rikers plan was being created. She worked for Andrew Cuomo before that when Cuomo was governor. I want to go back as we discuss closing Rikers or not as an emerging issue in the New York City mayoral race, go back and play the clip of Cuomo that made news last week that we played at the top of the segment. Play it again because that was 35 minutes ago. We're trying to give these issues a lot of oxygen to really explore them.

I hope this is serving you, listeners. Here's Cuomo last week, who came out with his new position. Used to be for closing Rikers Island.

Andrew Cuomo: We should rebuild new state-of-the-art jails on Rikers Island, provide free bus service, and use those existing sites for housing and commercial development.

Brian Lehrer: Okay, so that's the plan. Here's one of the reasons that he gave at that announcement as he compared all the delays in building the four borough jails that would replace Rikers Island. He compares it to, even though he uses the wrong word, to a big boondoggle construction project in Boston a number of years ago.

Andrew Cuomo: Let's make a major start by stopping a major debacle, which is the new jail construction to replace Rikers Island. The writing is on the wall. It promises to be New York City's best big ditch. It is already years late, billions over budget, and obsolete.

Brian Lehrer: He meant Big Dig, which was the name of that transportation renovation project in Boston. My understanding is that it worked out pretty well eventually, but Bostonians were pretty ticked as it dragged on and snarled traffic for a long time along the way. Anyway, there's Cuomo. Later that day, last Wednesday, Zohran Mamdani, the Democratic nominee, reacted.

Zohran Mamdani: Andrew Cuomo's proposal to take that which is broken, that which is morally bankrupt, that which is a stain on our city, and to keep it open. It's a betrayal, not only of the law as it stands today, but also of what New Yorkers actually want.

Brian Lehrer: Mamdani reacting to Cuomo. Here's Republican nominee Curtis Sliwa reacting to Cuomo.

Curtis Sliwa: In 2019, he had a press conference. "We must close Rikers Island." Two weeks ago, he once again reiterated. "It should have been closed a long time ago." Where would he have put the inmates back then? You can't trust Cuomo. He's the flip-flop guy--

Brian Lehrer: To that specific point of history in the Curtis Sliwa clip, Liz, true? What did Cuomo do in 2019 toward closing Rikers?

Elizabeth Glazer: I think that this was not really-- this was a city issue. This was not something the state was involved in. I have to say that I'm blanking a little bit on what he did in 2019.

Brian Lehrer: Maybe Curtis is referring to the Bail Reform Law?

Elizabeth Glazer: Could be. 2019 was bail reform.

Brian Lehrer: When did you work for Governor Cuomo?

Elizabeth Glazer: I worked for him 2013 to '16. First term.

Brian Lehrer: Same period of time when de Blasio--

Elizabeth Glazer: Sorry, 2011 to '13, yes. When he first came in.

Brian Lehrer: Just before de Blasio started, and you joined him.

Elizabeth Glazer: Yes.

Brian Lehrer: Was there any discussion at that time of closing Rikers Island as we continue with this oral history?

Elizabeth Glazer: No.

Brian Lehrer: All right. Almost everyone says that the 2027 closing date, which is the law right now, is not realistic, given construction delays at the proposed borough jails that Cuomo referred there, comparing it to the Big Ditch or the Big Dig from Boston. Do you agree with at least that much?

Elizabeth Glazer: Yes, I think it's pretty clear that as far as what the contracts now say and how the building is going, it looks like Manhattan won't be done until 2032. That's their current prediction. Brooklyn is the earliest, but that's not till 2029. Queens and Bronx are 2031, so really, a long time away.

Brian Lehrer: Let's say Mamdani is elected, who does support the current law and wants to close Rikers Island and transition to the borough-based jails. How does that happen?

Elizabeth Glazer: I don't think it does happen by 2027. I would say that as the date recedes further and further, the ability to actually fix things on Rikers also recedes. Because now that there's a 2027 date by which they're supposed to be off, the city can't use, for a whole bunch of kind of technical reasons, capital dollars in order to fix things, and so the facilities deteriorate evermore. I do think that it's a real question about is something that is state-of-the-art, air-conditioned, has good sight lines, is a decent facility? Does that get built [unintelligible 00:40:25] now on Rikers?

Brian Lehrer: Which is the Cuomo proposal, I think, right? To replace the old, decrepit Rikers buildings with this new state-of-the-art, that was his term in the clip, jail or jails.

Elizabeth Glazer: The question is how do you get from here to there, and what do you do right now for people who are on Rikers? There are a couple of things that have to be done and should be done, whether people move off the island or elsewhere, such as reduce the population. I think it is a question whether at least one facility is built on Rikers Island that is decent, as you begin to get people off, whether you open the hospital beds. There are supposed to be 330 hospital beds that are opened. Whether you figure out other ways, whether you accelerate the Brooklyn facility, which is closest to being built, but it is an impossible situation right now.

Brian Lehrer: Thank you for your oral history. Thank you for your policy analysis, Liz Glazer, who now has founded and runs the New York City policy journal, Vital City. We'll be reading Vital City. Thank you very much for joining us. For 30 Issues in 30 Days. Issue 17, closing Rikers Island or not, as an emerging issue in the New York City mayoral race. Thank you, Liz.

Elizabeth Glazer: Thanks very much, Brian.

Brian Lehrer: Again, tomorrow, Issue 18, which is going to be, should New York City move these mayoral elections to the same year as the presidential elections? That'll be tomorrow, but we'll turn the page and talk about something else right after this.

Copyright © 2025 New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.

New York Public Radio transcripts are created on a rush deadline, often by contractors. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of New York Public Radio’s programming is the audio record.