The Toll of Being MLK and His Final Months (Full Bio)

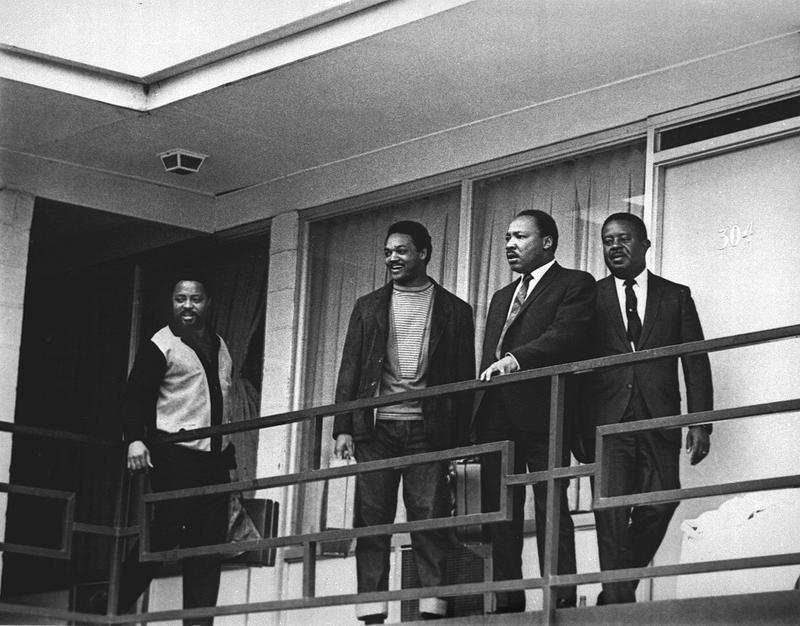

( AP Photo/Charles Kelly, File )

[music]

Alison Stewart: This is All Of It from WNYC. I'm Alison Stewart, thank you for joining us. I'm really glad you're here. If you couldn't be with us each and every moment, no worries. If you missed any of our conversations from this week, you can catch up on our podcast feed. Yesterday I spoke with British singer-songwriter Billy Martin, who performed live in studio. Such a gorgeous voice. I also spoke to Joe Anderson, the host of Slate's Slowburn podcast, which is focusing on Justice Clarence Thomas this season. He actually got to interview Justice Thomas' mother, and author Lorrie Moore, whose new novel is I am Homeless If This Is Not My Home. You can check out those interviews wherever you get your podcasts or head to our show page @wnyc.org.

Now let's get this hour started with our full bio conversation, the final part of our conversation about the life of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.

[music]

Full Bio is our monthly book series where we spend the week fully discussing a deeply researched biography. We have spent the week with Jonathan Eig, author of the first comprehensive biography of Martin Luther King Jr. in three decades. The book is called King: A Life. We'd arrived at MLK's final years. Eig notes that King's adherence to Gandhi's principles of nonviolent protest did not resonate with some others in the movement. Malcolm X found King to be too accommodating and passive as did younger Black Power leaders. The Old Guard and the NAACP, an organization founded 20 years before King was born was concerned about King re-swooping the spotlight and some funding. As MLK began to expand his mission beyond civil rights and into opposition to the Vietnam War, it created friction with President Lyndon Johnson, which provided an opening for FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover to stir the pot.

Hoover bugged King's home and hotel rooms and used what he found to discredit the leader. Here's my conversation with Jonathan Eig.

[music]

We should note, and it's very clear in your book and it's really interesting, that the Civil Rights Movement wasn't a monolith. You had Malcolm X and younger Black Power activists thinking that MLK was too passive and deferential. On the other end of the spectrum, even the NAACP wasn't always on board with Martin Luther King, Jr. What issues did the NAACP have with King?

Jonathan Eig: The NAACP was constantly struggling with how to deal with King. They saw him as a threat in a way to their power because King was drawing support, King was always thinking about the possibility of creating a membership for his organization, which would have undercut membership in the NAACP. The NAACP always felt like King was getting too much credit, that they were the ones changing the laws, and that King was just the loudest speaker and that he was getting the attention but the NAACP deserved the credit. There was this constant struggle. Even in Montgomery when the bus boycott was successful, Thurgood Marshall pointed out that it was really the court victory that sealed the desegregation of the buses, it wasn't the marchers who did it. Some of it was ego for sure.

Alison Stewart: You note that MLK grew up with a lot of female attention, his mother, his sister, his grandmother, yet he did adhere to the patriarchal nature of the civil rights movement. Ella Baker was a really big part of it, often felt overlooked. Rosa Parks wound up financially unstable. Even though Coretta wrote, women have been the backbone of the whole civil rights movement, it really wasn't apparent and his inner circle. Why was that? Why didn't he champion women's rights as fundamental as Black people's rights?

Jonathan Eig: Sadly, our great hero of equality and justice had a blind spot and that blind spot was women. He grew up in a very patriarchal society. The church at the time, the Southern Baptist Church was particularly patriarchal and they saw women as being in a role that-- their role was meant to stay home and raise the kids and Dr. King was really hampered by that prejudice. He was surrounded by brilliant women, he was married to a brilliant woman, they tried to wake him up, shake him out of that attitude but they failed for the most part. Ella Baker complained about it all the time. She said, it wasn't just King, it was the fact that the civil rights movement was led predominantly by Black Southern Baptist preachers and that they all shared that kind of bias.

Coretta Scott King talked about it often and even in her own memoir said that she appealed directly to her husband and said, "I want to be doing more, I want to be out there protesting." He said, "Your job is to stay home with the kids."

Alison Stewart: My guest is Jonathan Eig, the name of the biography is King: A Life. The stronger and more powerful that Martin Luther King Jr. got, the more intense the scrutiny was and the more dangerous life became for him. What kind of physical confrontations did he have? When was his life in danger?

Jonathan Eig: King's life was in danger all the time. Early days of the Montgomery Bus Boycott, his home was bombed, windows were shot out by a shotgun. Soon after that, he was stabbed in the chest in Harlem by a woman who seemed to have no real motive except that she might have been mentally imbalanced. He received constant death threats. He also became under attack by the FBI, which it knew that it was creating conditions by questioning King's loyalty to America by calling him a communist, by calling him untrustworthy, calling him a liar, that they were creating more animosity, that they were creating the kind of conditions that might stoke a madman or an angry man to come after King and then try to kill him.

Alison Stewart: In your book, there's the suggestion that he suffered from depression, that all of this and the power but also the responsibility began to take a toll on him. What were the signs that he may have had depression or at least there was a toll being taken on his mental health?

Jonathan Eig: There's no question that he was suffering emotionally. He attempted to commit suicide twice as a teenager. Corretta, in many of her writings, refers to his feelings as having depression, anxiety, that he needed sleeping pills to get any rest at times, that he drank at times when he was unable to sleep. We forget that he was hospitalized numerous times and talked about it, said it was exhaustion, but he was also heard on the phone with his advisors and we know these conversations because the FBI was listening in and we can read the transcripts, saying that he just needed time to stay in the hospital longer. He was asking his doctors if he could stay there longer to rest because he just wasn't emotionally prepared to get back into the game.

Even when he won the Nobel Prize, he was in the hospital when he got the news and he invited reporters to come to the hospital to interview him about winning the Nobel Prize. He told them quite openly that he was in the hospital because he was exhausted.

Alison Stewart: Did he ever consider walking away? Could you walk away?

Jonathan Eig: I don't think his faith in God and his morality would let him walk away. He talked about taking a break and his advisers were conspiring to see if they could get him some kind of an academic fellowship in Europe that might get him out of the cycle for a while because they worried about him, they really thought he was becoming depressed and losing confidence and that he was at risk just of breaking down but King felt like he couldn't step back, that it would be a failure of his morals, that God called on him to do this work and that he couldn't stop.

Alison Stewart: By the mid-1960s, MLK and Coretta have four children, two boys, Martin Luther King III and Dexter, and two girls, Yolanda, Yoki, and Bernice. How often was MLK able to engage in the ordinary duties of fathering?

Jonathan Eig: He wasn't home much. It was rare that he would spend more than three or four days in a row at home in those years. You can look at his calendars and see that he's traveling constantly, giving hundreds of speeches a year. When he does come home, there's still all these demands of the office in Atlanta and he's juggling just an incredible workload, he's juggling several women in addition to Coretta. Sometimes when he comes home, he goes to Dorothy Cotton's house before he goes home to see his wife and kids because Dorothy Cotton was his longtime confidant and she had a therapeutic effect on him. I think she was in some ways, the most calming influence in his life. All of that meant that family life was very difficult and very tenuous for him.

Alison Stewart: Is confidant a euphemism?

Jonathan Eig: Yes, it was his mistress. Dorothy Cotton was his longtime mistress and she acknowledged that to some of her friends in later years and people who knew King have acknowledged that but it was a secret that she kept all of her life.

Alison Stewart: There was a period when MLK seems conflicted about whether to intertwine the civil rights fight with the anti-war movement. Before we get into that, let's talk about his philosophy of non-violence. What was the origin of this philosophy for him?

Jonathan Eig: As a college student, King studied Gandhi and other non-violent philosophers, and really, I think felt drawn to it. It wasn't until he becomes an activist, till he is leading the bus boycott that he sees the effectiveness. Once he begins to use it as a strategy, it also becomes a deeper philosophy and a way of life. It ties in, of course, with the teachings of Jesus and the teachings of the Bible, which say that we should turn the other cheek and that we should love all of our brothers regardless of their nationality, and that all of us are God's children. King embraces that, and he says there's no way that he can endorse violence of any kind, and that includes war. There's no way that he can talk about stopping the rioting, the police brutality and not call out the war in Vietnam. It's all part of one much broader, deeper philosophy for him. That of course, leads to complications in his relationship with President Johnson.

Alison Stewart: Let's listen to Dr. King from a news conference held at the Belmont Plaza Hotel in Manhattan in February of 1968, addressing the war in Vietnam.

Martin Luther King Jr.: We need to make clear in this political year to congressmen on both sides of our and to the President of the United States that we will no longer tolerate, we will no longer vote for men who continue to see the killing of Vietnamese and Americans as the best way of advancing the goals of freedom and self-determination in Southeast Asia. It is imperative that church and synagogue leaders, clergy, and Lehman come to Washington, lest persons in the federal government think that men of conscience can be cowed in into silence by attack on dissenters or by blunderbuss indictments. It is time for all people of conscience to call upon America to return to her true home of brotherhood and peaceful pursuits. We cannot remain silent as our nation engages in one of history's most cruel and senseless wars.

Alison Stewart: Did it matter to MLK that he would lose the ear of the President, the support of LBJ as he came out against the war?

Jonathan Eig: King's advisors were warning him that this was a big mistake, that he was going to lose support in the north. The war was still fairly popular at this point, remember. LBJ was deeply enmeshed in the war. It was an obsession. It was causing him nightmares. King didn't care. He felt like he had to do this because it was the right thing. Something interesting that King's friend Andrew Young said to me was that King genuinely felt like he was a minister to LBJ, that he was going to help LBJ understand his own feelings, his own challenges, that he was ministering to LBJ when he talked about the war. That's how King viewed it. I find that really fascinating that he didn't see it as a confrontation at all. He wasn't worried about losing LBJ's friendship. He was worrying about saving LBJ's soul.

Alison Stewart: How did Dr. King feel about JFK's soul before obviously he was assassinated?

Jonathan Eig: King's relationship with JFK was complicated too. He was disappointed with JFK. He thought JFK had made a promise to the Black community that he was going to stand up for civil rights after winning the election in large part, thanks to Black voters. He was frustrated that JFK was being a politician and not a moral leader, that he was counting his votes and holding off on proposing civil rights legislation because he was worried that he might lose support in the South among white voters. This really frustrated King. He struggled with understanding why politicians could be so obsessed with polls and public opinion when they really ought to be focused on doing the right thing. Again, this goes back to him not thinking like a politician, but thinking like a preacher.

Alison Stewart: There's a third person we have to mention in this equation, J. Edgar Hoover, who--

Jonathan Eig: How did we not get around to that sooner?

Alison Stewart: [laughs] Well, we've done an entire bio series on J. Edgar Hoover with Beverly Gage, so our audience is probably caught up. Hoover was obsessed with King to the point where he named him a primary target for intel gathering. He thought King was a hypocrite because of his dalliances with other women. He was convinced that communists were pulling one over on civil rights leaders and that Black power and communism were going to become entwined. When did Hoover's targeting of King change the trajectory of King's career or the civil rights movement, whether or not King knew about it?

Jonathan Eig: The key moment is really clear. It's right after the march on Washington. King gives his greatest, most famous speech, I Have a Dream. He seems like he is offering America a new way, a path out of its racist history, a path forward into a true united community of brothers and sisters. Literally, you see on TV, Black and white people holding hands and singing in harmony. King is offering us a new image of America. That becomes an enormous threat to J. Edgar Hoover and certainly others within the FBI, but also others in the American power structure who want to preserve the status quo. Right after the march on Washington, the FBI produces a memo saying that King must be perceived now as our greatest threat. Whose greatest threat?

Well, the white power structure's greatest threat because he's clearly not a threat to American democracy as we understand it today. It's all about who's in charge. J. Edgar Hoover has built his whole career on making sure that those in charge stay in charge.

Alison Stewart: After the break, we'll discuss the last months of MLK's life. This is All Of It.

[music]

Alison Stewart: This is All Of It from WNYC. I'm Alison Stewart. We conclude our June full bio conversation about King: A Life by Jonathan Eig. In the mid-1960s, Martin Luther King Jr. expanded his message to include eradicating poverty in the United States, tying economic inequity to civil rights. Here's some audio from the New York City Municipal Archives, WNYC collection of MLK Jr. from an appearance in Harlem in 1964.

Martin Luther King Jr.: There are some 10 million families comprising between 40 and 50 individuals who are poor people. They find themselves on a lonely island of poverty in the midst of a vast ocean of material prosperity. If America is to be a great nation, she's got to solve this problem.

Alison Stewart: King wanted to bring economic justice into his message, but his aids were dubious when he announced a so-called Poor People's protest in Washington DC. This event was still in the planning stages when Dr. King went to Memphis, Tennessee in April of 1968 to support striking sanitation workers. Here's the last installment of my conversation with Jonathan Eig, author of King: A Life.

[music]

Alison Stewart: King announces that in the spring of 1968, the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, the SCLC, would lead what he hoped would be a movement called The Poor People's Campaign. It would be a march and a protest in Washington DC where a shantytown would be built as an act of civil disobedience. He called it "The last nonviolent approach to give the nation a chance to respond." What led up to this decision to take this route? Let's just leave it there.

Jonathan Eig: King had been saying for years that the problem was not just the South, that it went far beyond that, and that America had to confront racism, economic inequality, militarism, materialism, all of these things. He wanted to shift the civil rights movement to a human rights movement. He thought that there was a chance to really change the dialogue and really reshape the whole American economy, the whole view of how we focus, how we treat poverty, and how we treat hunger. He thought there was a chance to make America new again. This was really also in part a response to the fact that he was losing popularity in those years. America had turned against him in many ways especially as he began to speak out more on issues in the North and when he began to speak out more on the Vietnam War.

A lot of people felt like he should have just stuck to the South where he was most qualified in their view to do his work. King, instead of retracting and retreating, he doubled down on his beliefs. He went back to his core philosophies that come from childhood, from the Bible, from his studies as a seminarian. He went as far and as wide as he could in trying to shake up the world and really give us a chance. That's what he was hoping for with this Poor People's Campaign. At the same time, it felt like a desperation move to many that he was just taking one last wild shot at something when he appeared to be failing in fact, to be honest.

Alison Stewart: Bayard Rustin, architect of the March in Washington, long-term advisor declined to be involved with the Poor People's Campaign. What did he see as the problem? Was he correct?

Jonathan Eig: Well, if you're cynical about it, you might say he was correct. Rustin said that the best thing that King could do is focus on the South and getting more people registered to vote and that if you got more Black people registered to vote, you could change the balance of power. You could get Black people elected as mayors. You can get Black people elected to state houses throughout the South, and you would shift the balance of power in Congress too, and that suddenly it would be much easier to pass really meaningful nationwide legislation to help the poor, to help Black people gain civil rights, to help protect voting rights. If you're taking this cynical approach, he might have been right. That might have been the most practical thing for King to do.

At the same time, King is not a politician. He's not just interested in a crusade for votes. He's interested in challenging America to be a more moral society. As he said over and over, fundamentally, he's a Baptist preacher at his heart and at his core. That's what he's doing. He's asking us to really look deep within our souls, the whole soul of the country. He's trying to save us.

Alison Stewart: I was struck by a number in the book. Please correct me if my analysis is off. Even though he faced all these troubles, declining popularity according to the press, he was still a go-to person in times of struggle. He was asked to come to Memphis in March of '68 because there'd been the sanitation strike and some unrest following the arrest of four Black teenagers. You note that people waited hours, some 10,000 people showed up for him. I'm wondering how much of this narrative of his troubles is from the press at the time if that many people showed up.

Jonathan Eig: That's a great point. King is 39 years old. He's been at this for 12.5 years, and he's still, despite his controversies, despite the emergence of other voices like Malcolm X and Stokely Carmichael, he's still the most powerful Black man in America with an ability to really move people and churches, Black communities, it's like a saint is walking into the room when he steps into the room. They believe in him. That's why when the strike erupts and sanitation workers in Memphis need help, and they feel like they can't get the city to respond to their demands, even after sanitation workers have been dying on the job from unsafe working conditions, who do they call? They call King. He's the only one that they think can rescue this situation and he's getting those kinds of calls from all over the country all the time.

He's still an incredibly vital, incredibly powerful force in American society, and especially, he's still deeply beloved by most of the Black community.

Alison Stewart: My guest is Jonathan Eig. We're talking about the biography, King: A Life. MLK returns to Memphis on April 3rd, and you note that the local newspapers named his hotel, the Lorraine, and even named the exact room. The FBI often planted stories and tipped off reporters about King with information, where he was staying. Was there any sense that they did so about the Lorraine?

Jonathan Eig: Well, there's no question that the FBI was still harassing King. Just months before this proposed march in Memphis, the FBI sends out a memo saying that King must be considered the most likely Black Messiah, that if anyone is going to unite the Black community to attempt to force significant change in American society, it's King. He must be treated as a dangerous rival. He must be treated as somebody who poses a threat to the status quo, and we must do everything in our power to obstruct him. That means embarrassing him. That means trying to create divisions within the civil rights movement, and yes, it means publicizing where he's staying and trying to embarrass him for staying at a white hotel the last time he was in Memphis and making sure everybody knew that this time, he was going to be at the Lorraine Motel.

Did that mean that the FBI wanted someone to assassinate him? I wouldn't go that far, but they certainly knew that they were creating conditions that could make that happen.

Alison Stewart: Where was Martin Luther King Jr. going the night of April 4th of 1968?

Jonathan Eig: He had just, the night before, given his famous mountaintop speech, and the next day, he was getting dressed to go for dinner at the home of another preacher in Memphis. He was on his balcony getting dressed, talking to some of the men down in the parking lot, joking around with them, asking a band leader, a saxophone player to play one of his favorite songs that night at the rally for the sanitation workers. Joking with Ralph Abernathy about what they were going to have for dinner that night, and talking to his driver about whether he needed a jacket because it was getting chilly. He seemed to be in good spirits.

Alison Stewart: He only lived an hour after being shot in the head on that balcony at the Lorraine. Almost his whole life, he had said he wasn't really afraid of dying even though he'd been stabbed, he'd been punched in the face and the head, thrown in jail, beaten, but not necessarily afraid of dying. Why not?

Jonathan Eig: I think he felt like he was not afraid of dying because he knew he had given his life however long it may be to the commands of God, to the words of Jesus, that he had lived his life in an effort to make other people better, to make the world better, and that longevity is not everything, it's the quality of the life you lead, and that he had done everything he could to lead a moral and a godly life.

Alison Stewart: King is often credited with holding the country together when it seemed like it would split apart. Is that a fair assessment?

Jonathan Eig: I think it is a fair assessment. I think he was a voice for a reason. He was a voice that Black and white people could come to respect and at least listen to. He almost forced you to listen even if you disagreed with him and he listened to others too. He listened to the white segregationist, he debated with them. He listened to Malcolm X and Stokely Carmichael when they disagreed with him. He encouraged us to be better, to think more like a community, to look for what we had in common with one another. That's why when he died, I think that the communities exploded because there was this sense that we had killed off the best of us, that we had snuffed out the life that was trying to lead us to a better place, and that's why you see riots, and exploding, and rebellions all over the country.

Alison Stewart: Jonathan, is there anything about the legend of Martin Luther King Jr. that you hope your book corrects or puts an end to, or maybe even just illuminates?

Jonathan Eig: Most of all, I hope that the book helps people see that King was human, that he was a real person, and that he struggled, that he had doubts, that he had joy and pain, and that he knew he wasn't perfect, and we don't need him to be perfect either. I think too often, we want our heroes to be saintly. One of the problems that we have with King in celebrating him is that we tend to sugarcoat his story and we focus only on the simple messages as a result of that.

We talk about I Have a Dream and Content of Our Character, and we forget that he was really challenging us to be better. He was radical and he was not afraid to force us to confront our flaws. I hope that the book will introduce King to people in a way that they make them feel that they could get to know him as a real man.

Alison Stewart: When is the next time that there'll be a trench of information or material released about MLK and his life?

Jonathan Eig: Well, I believe another dump of documents is coming in December from the FBI. Then in 2027, we're expecting a big moment when the tapes of King's recordings, the FBI's recordings of King from his hotel rooms and from his phones will be released. That information has been sealed. Nobody has heard those tapes and that will be an important revelation.

Alison Stewart: How are you feeling about that?

Jonathan Eig: I'm feeling fine about it, to be honest, because I think one of the great reactions to this book is that people have been willing to accept and embrace King's flaws, that in some ways, I think people find him more inspiring when they know he wasn't perfect, and we've been well prepared. We know that he was not a great husband. We know that he had affairs with women other than Coretta, but I think we can handle that and still draw inspiration from his life.

Alison Stewart: The name of the book is King: A Life. It Is by Jonathan Eig. Jonathan, thank you for giving us so much time.

Jonathan Eig: Thank you. I enjoyed it.

Alison Stewart: Thanks again to Jonathan Eig for his time and work. Also, shout out to Simon Close for the post-production on this full bio, and Jason Isaac for being our engineer. Thanks to WNYC archivist, Andy Lanset for providing us with the audio from the NYC Municipal Archives, WNYC Collection.

Copyright © 2023 New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.

New York Public Radio transcripts are created on a rush deadline, often by contractors. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of New York Public Radio’s programming is the audio record.