Thurston Moore’s ‘Sonic Life’

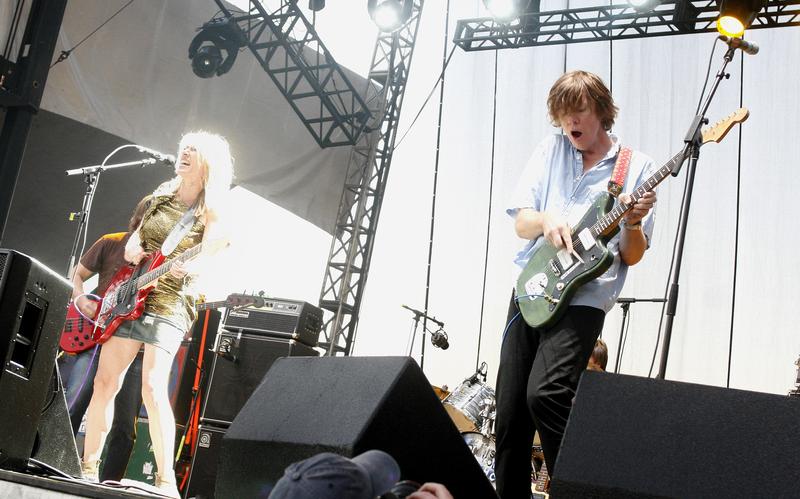

( AP Photo/Jack Plunkett )

[music]

Alison Stewart: This is All Of It on WNYC. I'm Alison Stewart. Before you get to the first word of Sonic Youth co-founder Thurston Moore's memoir, there's a photo dated 1976 with an image of a 16-year-old Thurston, headphones over a mop of blonde hair and the blurb says, "Immersive listening of Lou Reed's double album noise masterwork Metal Machine Music on heavy rotation in my rural Connecticut bedroom." Titled Sonic Life: A Memoir, Moore takes us through his lifelong relationship with music from that Bethel, Connecticut bedroom through making moves to gritty New York City in the late '70's to the vibrant, edgy music scene of the early '80s as bands like Sonic Youth emerged while living the life of young artists, a time when Jenny Holzer, Patti Smith might happen to be in the audience.

The book will take you back to the days when a Village Voice review was a big deal and creative people could still afford the East Village. At one point, Moore was living at 512 East 13th Street for $110 a month. Yes, that was in 1978. The memoir is heavy on music, not intimate moments. If you're looking for details about his marriage, divorce, and remarriage, this is not that book. It is, as Kirkus Reviews writes, "A self-aware, charmingly rough-and-tumble tale of the rock and roll life." Sonic Life: A Memoir will be out tomorrow. Thurston Moore joins us now from London, which is his current home base. Hi, Thurston.

Thurston Moore: Hi. How are you?

Alison Stewart: I'm well. We thought you might be able to be in studio for this interview. We were all excited. I think some of your fans know you can't travel right now because of a health reason. First of all, how are you feeling?

Thurston Moore: Well, I feel good right now. It's great talking to WNYC, which I used to listen to quite a bit when I was living in New York City all those years. It's just really cool. I have a bit of a heart condition. It's a typical atrial fibrillation, which a lot of people have especially people in their mid-60s, such as myself. I've had it for a number of years. I've had medication that would let it subside and control it. This year, this summer, I started feeling really crazy. I could hardly walk up and down a stairwell let alone go around the block, and it was intermittent, but it was enough to lead me back to talk to some cardiologists and such.

After I had some testing done, it was pretty much decided that I needed to have a bit of a procedure to take care of it. It's highly successful. It's very common. I'm not too anxious about it, but it was this call to stay put and ingest blood thinner meds and stay out of airports and all that kind of stuff. I said, "Well, I have a US tour to campaign my new book starting next week." They said, "Well, how many flights is it?" I said, "Well, it's a flight every day. It's like 30 flights." They were like, "You're crazy. You can't do that. Probably, if you did, God only knows. Please don't." Et cetera, et cetera.

Priorities being what they are, I decided to stay here, ingest my meds, and feel groggy, and wait for this procedure to happen. Then hopefully I can get back to Heathrow and fly to JFK and enter into the fray of seeing everybody. I have a lot of family around New York, and New Jersey, and stuff like that, and Florida, and so I want to go and see everybody.

Alison Stewart: Sure. We'll be here.

Thurston Moore: See my old friends. Oh, well, thank you. [laughs]

Alison Stewart: We'll be here. What did that Lou Reed album you were listening to in that picture mean to you as a teenager?

Thurston Moore: Oh, that record Metal Machine Music, when it came out, it was a little misleading because the cover of that record showed Lou Reed looking really amazing in front of a microphone as if it was a live hardcore Lou Reed statement. It was a double album for God's sakes. Anybody who bought that record just on impulse knowing Lou Reed's music with and without The Velvet Underground was probably just completely and utterly shocked bringing that record home because it was Metal Machine Music. It was this idea that he had of just creating these reel-to-reel tape loops that were just spinning in such a way that they're creating this whole otherworldly noise and overtone and of rainbow arcs of sound. I was fascinated by it.

There was a review in Creem magazine at the time by Peter Laughner, who was one of the original members of Pere Ubu, a really interesting character coming out of Cleveland, Ohio, and was part of that whole scene that exchanged ideas with New York City, so like television and Peter Laughner's band Rocket From the Tombs who had a connection. He also wrote for Creem magazine, and he had a review of Metal Machine Music where he just wrote the word no like 1,000 times. [laughs] For me, that was the perfect review for the era of just pre-punk. It's just like this completely nihilistic negative take on a record where it's like, no, no, no, no, no, no. It just made me love it all that much more. I knew that I was listening to probably the coolest record ever made.

Alison Stewart: You credit your brother, Gene, though, with really getting your guide into music. He introduces you into music. I wonder how much of that was the music itself and how much was it just admiration for an older sibling? Was it some combination?

Thurston Moore: Certainly. I trusted my brother's aesthetic taste coming into the house with a record like Louie Louie by the Kingsman in 1963. It certainly was the first rock and roll music I ever heard, and in some ways, I identified it with my brother. I didn't really elaborate on the story with that record and my brother in the book to the extent. What actually happened is he would tell me, as a 5-year-old and him being 10, he told me that him and his friends had recorded that record. At five years old, you believe anything that your older brother or sister will say.

He would stick his head out of his door of his bedroom where this cheap stereo was, and he would mouth the lyrics, which God only knows what those lyrics were. It didn't matter what he was mouthing per se and I believed him. I said, "Well, my brother recorded this really basic record." That was dispelled pretty, pretty quickly. For me, it was the first time hearing something that you thought you could personally identify with as far as being a young person coming up in a world where rock and roll was becoming taken more seriously. I don't think it was taken more seriously until the late '60s into the '70s, but I think certainly a band like The Beatles or The Rolling Stones did not shy away from bringing in more serious intention into this music, which was a teenage post-'50s rock and roll. It was for the kids.

In some ways, as they got older, the music got older too in relation to their own sensibilities. That was really significant to grow up with in the '60s and '70s, to grow up with these rock per people, personages, whatever you want to call them, like The Beatles. Lennon, McCartney, they were always sharing ideas that they were as adult, as they were as young adults. That was a great class in what was going on in the avant-garde. Paul McCartney was always sharing his interest in the avant-garde in the different disciplines of the art world in his music with The Beatles.

You certainly hear it on a record like The White Album with these ideas of collage and pastiche that were happening in the most marginalized corners of rock music. He was bringing it into the most famous band in the world for God's sakes. I don't think you can overplay the significance of the Beatles of introducing sophisticated ideas into an art form that was at once considered utterly juvenile.

Alison Stewart: My guess is Thurston Moore, the name of the memoir is Sonic Life: A Memoir. Just as you were about to come to New York City and figure out your life as a creative and a musician, your father passed away suddenly. You're pretty young. When you look back on it and you think about a life lesson he taught you that's still with you today, what would that be?

Thurston Moore: Well, that was certainly a catalytic year. It was '76 and it's a year that my father passes away. He's somebody who introduced an entirely musical world into our household, which I took for granted, but realized at some point that not all households had a grownup in there that was bringing art, and literature, and music into the fabric of the household. Only because I would go visit friend's house and there would be nothing there except for bric-à-brac and frozen food and a TV set that's on from day and night. I knew that my household was different. There was prints of like fine art on the walls, and there was all this philosophy in the bookshelves and my father was playing Rachmaninoff on the piano all day long.

I just thought that was normal, but it really wasn't normal. [laughs] With his passing, I realized that he was this great mentor for my own sensibility. I treat the passing of my father as a very critical juncture in my life. I try to stay away from the more sort of sad energy of anybody's life, regardless of whatever your relationships are, whatever your emotional connections are to other people. It was a very conscious decision to just focus on the joy of actually going towards a vocation that you decided to allow yourself to be part of regardless of poverty. [chuckles] That to me was important, I wanted to talk about how this belief in what the good is in any situation is the strongest energy, the strongest element.

I didn't really want to name-check too much of what happens in my life particularly since it was a book about myself, about these situations that have more darkness to them because I just figured I just didn't want that to exist in my book. I wanted my book to be this more, this template of bliss if that makes any sense.

Alison Stewart: Well, you get the sense of reading the book about how much you enjoyed playing in New York as a young man. Whether it was with Sonic Youth or the Coachmen. It's like CBGBs and the Hilly Kristal days. Did you have a particular club in your memory that you really just really liked playing in?

Thurston Moore: Well, to play it a club like CBGB for me was completely a dream made manifest after having spent so much time there as a witness in the late '70s. Maybe I felt a little more connected to the demographic that was hanging out between Tier 3 that was below Houston Street and Mudd Club which is a few blocks away below Houston Street. It's even further south club scene. Tier 3 only lasts for one year all through '79, Mudd Club a little longer, but in a way that's where our community was more so than CBGB. The community of CBGB of the 1970s was those pioneers of the Ramones and Patti and Blondie and talking heads and stuff.

I didn't hang out with those people. They were older than me. I was like a kid just going there. I wasn't friends with Richard Hell until late '80s for God's sake. Tier 3 and Mudd Club were people my age who had gravitated to the city, to want to be near that work, that energy. I felt like that was more of the scene that I felt associated with. I would say I would say Tier 3 for sure was the clubhouse. If I had to pick a clubhouse in downtown New York, that was it. There's musicians I was playing with in the Coachman who we all hung out with each other, but I didn't belong to some big downtown community.

I would interact with people to some degree, but I talk about Jean-Michel Basquiat in the book quite a bit because he figures so prominently, it's just in the culture downtown. We're not hanging out, we maybe nod and say hi to each other, this kind of thing because we're always in the same places, but we're not friends in that certain way. There are other people that we have mutual friends. Somebody like Jim Jarmusch the filmmaker, he's a really old friend of mine that I meet in New York before he becomes a celebrated film director. He's also very friendly with Jean-Michel.

There's these connections and there's all this mutuality going on, but you didn't think about that at the time anyway. There was no analysis of it. It was just everybody recognized each other. There was no media eye on what was happening, and so there was no instructive there. That would happen later when all of a sudden everybody was interested in what was going on, but there was no interest beyond our interest, and so it was able to be self-cultivated.

Alison Stewart: We're talking to Thurston Moore the name of the memoir is Sonic Life: A Memoir. You said 1986, you write in the book in chapter 51 that 1986 was when you truly learned to tour. What does it mean to truly learn to tour? What did you have to learn to do?

Thurston Moore: Well, you learned the pitfalls and the ins and outs of what it means to tour. You learn that it's probably a good idea not to spend whatever coin you have all in one day, [laughs] because there was no money anyway, so you learned how to take care of business to some degree. Some bands I know that are contemporaries would've gone out, and the whole thing was just get in the van and hopefully, the gig you played will be enough money to pay for gas. Then everybody is drinking beer and smoking cigarettes.

You're young and rowdy, and it's just one for all and all for one, and it's a very quick process of getting burnt out on that because just without no sleeping, and a lack of responsibility towards each other and towards your own decision to be in this vocation. A lot of bands just don't last beyond two, three, four years. Some of them just flare up and become really popular for two, three, four years and then they're gone, or they take a break and they regroup and they've learned their lesson of how to keep it together. Some people have issues with getting involved with this hardcore lifestyle through the rest of their lives, and they can't ever break free from it.

I think we, as a group, the way we found each other, I think we recognized a sense of how to recognize what the responsibility was to be in a band, especially with a band playing music that was really on the margins of what most music was happening in that scene at that time. We were truly an experimental band. There was bands that were way more out on left field than we were, but they didn't really get too far at all. We had a balance between being really far out, and a little somewhat far in. This idea of traditional aspects was completely experimental aspects. We liked that, playing with that balance.

It allowed us to attract more attention to what we were doing as an experimental band, and to, at the same time, challenge any listener who was only interested in the more accessible nature of the bands like us coming out of the scene that we were coming out of. What we learned is just what worked on stage, what we were doing with the different tunings of the guitars and how we were treating these guitars. What worked on stage, what worked for us as people crammed into a small space together on top of each other and knowing that you had to get through days of living this existence. It was this recognition of what that comradery was.

Of course, there would be some headbutting and some growing pains. I think what we learned is that if there was a way to actually subsist as being a band even though there wasn't much remuneration there, you could still be doing work as an artist and get recognized. It's just the recognition was-- That was the most value of anything, more so than money, or good reviews, or whatever. Well, good reviews are good recognition, but just for people coming up to you and really appreciating what you were up to and being turned on by it, being intrigued by it. That was where most of the actual positive value was.

What do you learn? You learn you learn how to bring your A-game to the stage every night regardless of how many people are out there.

Alison Stewart: What was challenging about writing your memoir, Thurston?

Thurston Moore: I just wanted to write. I've always been engaged with writing. I do a lot of publishing with poetry journals. I teach a writing course at the summer writing workshop at Naropa University for the last seven, eight years. I've never written a long-form piece of any sort. I figured the memoir, as a device, would allow me to do that. I certainly had been asked if I was ever going to write a memoir and I was like, "I don't really want to write a memoir. I do want to read a history of the band from my own prism. First, I wanted it to be meta where as experimental as any Sonic Youth song could be, but then I also realized that there is a factor of inaccessibility there that might not be the best tone for a book like this. It was selfish because I thought I wouldn't be able to hold on to any strand of narrative if I did that. I probably after 100 pages just like, "Oh, forget about it." I decided to really focus on the chronology of the band and do intensive research at libraries, locating the places that the band hit all the way from their beginning.

A lot of which is online on the sonicyouth.com site but I know that there was a lot of gaps there and I really needed to go into regional newspapers, particularly The Village Voice where I had to locate the only place in America that had full microfilm of the entire run of The Village Voice, which happened to be at a library in Fort Lauderdale, Florida.

Alison Stewart: Wow.

Thurston Moore: I got down there.

Alison Stewart: It actually seems fun. It sounds fun.

Thurston Moore: Yes, it was fun. It was during a pandemic, so libraries were opened or closed at any given time. New York Public Library didn't have hard copies or a full digital of it. I had to go to the Library of Congress, and that's like a warren of data there. Finally, it led me to this one library in the USA that had a full run of microfilm, and it happened to be that Fort Lauderdale Library, thank God. I went there, and I spent days upon days upon days just rolling through their archives and finding Sonic Youth-related stuff, but I would get sidelined by so much incredible cultural information which you can only imagine of The Village Voice. I was able to put it on a thumb drive.

Subsequently, I have this amazing archive of information and data in regards to the band and the culture of the band. The communitarian culture of the band because Sonic Youth was always a community-conscious band as far as working with other musicians and artists. I think I've strayed away from what you had asked me-

Alison Stewart: That's okay.

[laughter]

Thurston Moore: -by going off into this. [unintelligible 00:22:44].

Alison Stewart: The name of the book is Sonic Life. Thurston Moore Sonic Life: A Memoir. It is out tomorrow. We look forward to seeing you back in New York and to seeing you in good health. Thurston, thanks for being with us.

Thurston Moore: Thank you. I really appreciate this. It's wonderful to talk to you.

Copyright © 2023 New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.

New York Public Radio transcripts are created on a rush deadline, often by contractors. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of New York Public Radio’s programming is the audio record.