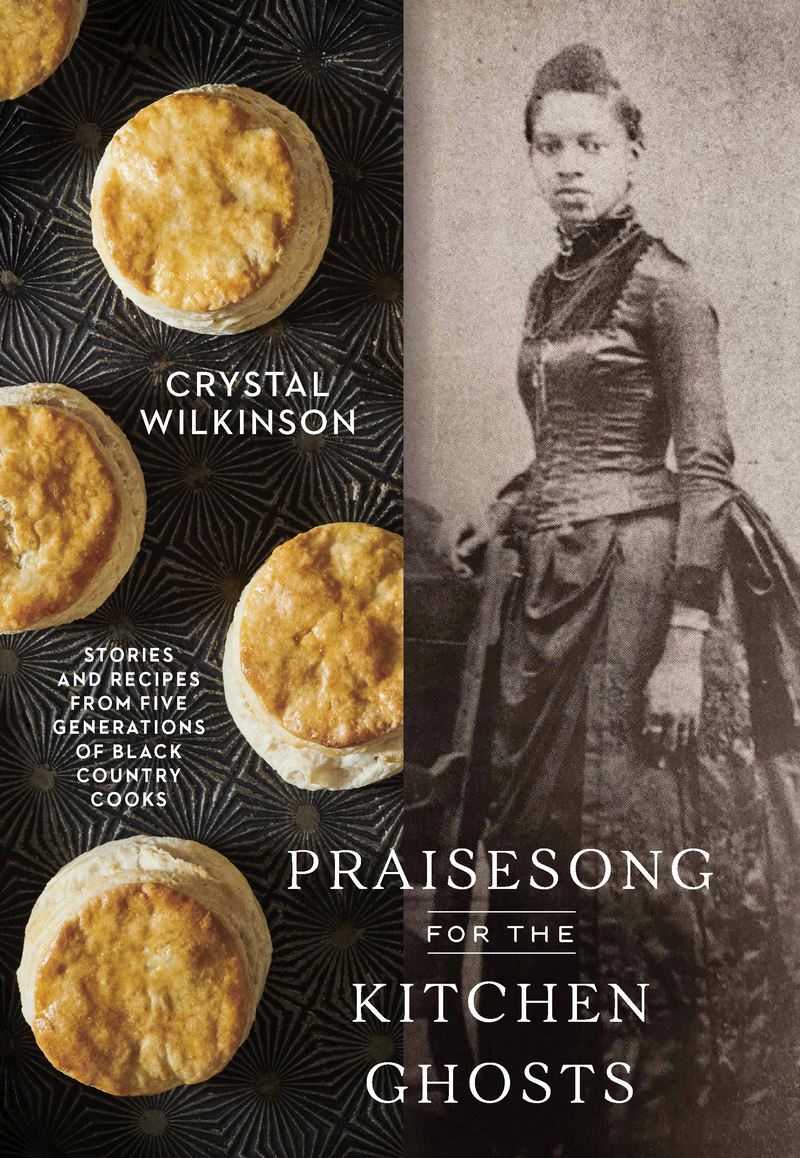

Stories and Recipes from Black Appalachian Cooks

( Courtesy of Penguin Random House )

[music]

Alison Stewart: This is All Of It on WNYC. I'm Alison Stewart. In a new memoir, a writer, educator, and one-time Poet Laureate of Kentucky, Crystal Wilkinson, celebrates the contributions of Black Appalachian women in her family through food, weaving their stories together with recipes and family photos. It's called Praisesong for the Kitchen Ghosts: Stories and Recipes from Five Generations of Black Country Cooks. She writes in the book, "The concept of the kitchen ghost came to me years ago, when I realized that my ancestors are always with me, and that the women are most present while I'm chopping or stirring or standing at the stove. The art of cooking and engaging with my kitchen ghosts made me realize that food is never just about the present. Every dish, every slice, every crumb, and kernel tethers us to the past."

Using elements of poetry, prose, and fiction to reflect on her childhood and upbringing and pastimes, Wilkinson writes about the culinary traditions that spanned two centuries. Then there are other recipes, some as simple as two ingredients, some taking their names from the region like Indian Creek skillet cornbread, and a whole chapter about blackberries. Biscuits with blackberry soup, blackberry cobbler, and wild blackberry lemonade. Praisesong for the Kitchen Ghosts is out now. Crystal Wilkinson currently teaches at the University of Kentucky in the creative writing MFA program. Welcome to our studio.

Crystal Wilkinson: Thanks for having me.

Alison Stewart: You write in your introduction, "People are always surprised that Black people reside in the hills of Appalachia." How did Black folks come to Appalachia?

Crystal Wilkinson: Well, I think Black people came to Appalachia in the ways that they did other places, through enslavement. Primarily, people don't often think about enslavement in the mountains, and it was different than like the large plantations in the south, but Black people were definitely there, working more closely with their enslavers on farms, in kitchens, in small businesses.

Alison Stewart: What's something unique about the food and the food culture of Black Appalachia?

Crystal Wilkinson: I think people are always comparing it to the South, and I love Southern cuisine, but I think the difference has to do with the landscape. If you can't grow food in the winter, then you have to do a lot of preservation. The preservation of pigs, for instance, instead of having a big barbecue, it was all about preservation. Salting the pork and putting it away for the winter, doing hams, putting them away for the winter. With the terrain, we were more apt to grow kale and turnips instead of the Southern collards. I think the terrain and the soil, and the difference in the work made it a bit different. The crux was then on preservation.

Alison Stewart: When you talk about soul food in the mountains, is this what you mean? What is Black Appalachian soul food as compared to, let's say, Georgia or North Carolina?

Crystal Wilkinson: Yes, that's what I mean. I think some of those foods that are preserved for their struggle, for the winter struggle. I'm always talking about the potatoes. When I was a little girl, my grandparents would get the potatoes and I'd have to put them in the attic so that we would have potatoes all winter. They would be up there, and I would be sent with my little bucket to get the potatoes. Come March, they'd get more and more-- they never rotted, but they get more and more shriveled down. That worry, cooking and worrying, like, "Are we going to have enough to go through the winter?"

Alison Stewart: About survival.

Crystal Wilkinson: Yes.

Alison Stewart: Preservation in many ways.

Crystal Wilkinson: Yes.

Alison Stewart: Many meanings for the word preservation. Part of what you write about in the book, which is really interesting, is you write about traditions, not just the food itself, not just your family story, but also things like Sunday dinners and dinners on the grounds, which can be traced back to enslaved people getting their rations on Saturday nights. Why do you think it's important to know the history behind these traditions, these food traditions?

Crystal Wilkinson: Well, I think it's important because it's still with us. Even if we don't know, I think Black Appalachian culture has it, and I think every culture has it. These kitchen ghosts, the way you do things, the foods you eat, are like your ancestors did, and they were passed down, whether you know that or not. I talk about the way my grandmother cooked is even in my body. I see her. Sometimes, I'm like, "Okay, there it is. I've almost got it." Then there's my grandmother enter the picture like, "Oh, that's exactly how she would do it."

Alison Stewart: What are some of your earliest memories of being in the kitchen?

Crystal Wilkinson: I think my absolute earliest is standing on a chair, watching her cook. Being so close. Probably in modern times, someone would call CPS. I was so close. Standing in the chair, watching her cook, trying to peek over to see, not only what was in the pot, but how she was preparing it, how she was seasoning it. Then the wonderful smells being that close up. All these facials from the steam.

Alison Stewart: My guest is Crystal Wilkinson, the name of the book is Praisesong for the Kitchen Ghosts: Stories and Recipes from Five Generations of Black Country Cooks. You introduce us to many of your family members. You reference one whose name is Aggy. Tell us a little bit more about Aggy, how you were able to find out about Aggy, what you want us to know about Aggy.

Crystal Wilkinson: Aggy is the relative that tethered me to history the most. She was born in 1795 in Virginia, she was brought to Kentucky as Kentucky was being formed in the early 1800s as an enslaved child. She married, common law married her owner, who was my fourth great grandfather, Tarlton, and they begat us. When I found her, the legacy of all of that became-- as a professor, as someone who knows the history of the country, being able to see it through my ancestry, to see on a document, her being called Aggy of Color, and the weight of knowing what that meant, and not only for my personal ancestors, but for all of us.

Anybody who's African American, and particularly women. This legacy of Black women, and all of these unnamed Black women, who were Aggys too. The legacy of all of that, the weight of all of that, just really hit me when I found her, and it was very emotional. She's haunted me into writing about her, not in a bad way, not in a gross way, but in a very poignant way of, "It's your duty to tell my story."

Alison Stewart: To document. To make sure people know, "I was here, and I meant something, and I left a legacy." Did your people talk about history? Some families don't like to talk about it, or they say, when you're a little kid, "That's grown folks' conversations." When you start asking too many questions, especially when there might not be happy memories.

Crystal Wilkinson: Yes. My grandmother wouldn't even say the S-word. She would not say slavery. She said, "Oh, nobody wants to talk about that." She did not talk about that. I discovered that Aggy's daughter was Patsy Riffe, who's on the cover of the book. I discovered this photograph, this beautiful photograph of an elegant Black woman, and I just remember I kept touching it. She had always been in the history of my county, and all the historical records. This beautiful Black woman, who was Patsy Riffe, but I never knew who she was, but there was a ridge named after her.

There was a Patsy Riffe Ridge there in Indian Creek, Kentucky. My grandmother would say, "Oh, she's a colored woman, and she's somewhat keen to us," but in the history books, it would say that she was a beautiful, Black businesswoman, colored businesswoman, and that her father was a white wealthy businessman, and that her mother was a slave. I'd seen that, not realizing she's somewhat keen to us, not knowing what that meant, but also not realizing that her mother was Aggy. That was another really emotional moment when I made that connection, that everywhere she's listed, slave woman, her name was Aggy.

Alison Stewart: How did women in your family pass down the recipes? Was it oral tradition? Did they write on note cards and they had a little card box? How did it happen?

Crystal Wilkinson: It's absolutely oral tradition. I say that recipes are like poems. They're meant to be both oral, spoken, and oral like listen to. The cadence in the voice, especially where I'm from, you can hear my accent, but the cadence in the voice, the way that my grandmother would tell them. "First, you're going to need this bowl. Then you get that bowl out, and then what you're fixing to do is this. You'll need just a dabble of that. Not too much now. Don't put in too much salt."

The cadence of her voice and the way she told me the recipes were oral first. Then when I was a young girl going into home ec class for the first time and had a recipe box, I asked her for recipes and she really wouldn't give them to me. I said, "Well, you just tell me what they are and I'll write them down." Many of the recipes in this book came from that writing down that I still have in that little recipe box that I've had since I was 12 or 13 years old.

Alison Stewart: Do the cards have stains on them and from all the work?

Crystal Wilkinson: They do. There's rust on the box, there's stains on the cards. Yes, there's a lot of history even in that in the box. Then there are some recipes that she wrote out by hand that are on my notebook paper that she wrote out with her beautiful handwriting, and I have those too.

Alison Stewart: We're discussing Praisesong for the Kitchen Ghosts: Stories and Recipes from Five Generations of Black Country Cooks. It is out now. My guest is its author, poet, and educator, Crystal Wilkinson. I want to ask about a couple of recipes while we have some time. Indian Creek chili, which is on our website for people, if they want to take a look at it. What makes this dish unique?

Crystal Wilkinson: I think where I'm from, what always makes it unique, and maybe it's because we're close to Cincinnati, where some of the putting pasta with chili started. There's always pasta. There's no such thing as just meat chili with beans. It always has to go over spaghetti. I think that that makes a big difference. We were also people not prone to really hot flavors, so it's a very mild tomato-based chili. I think both of those things makes it unique.

Alison Stewart: Blackberries seem very important. Why are blackberries so important?

Crystal Wilkinson: I think blackberries were these little purple glistening heirlooms. One, they were hard-won. You had to do a lot, you didn't go to the grocery store, so you had to put on boots and long sleeves and be doused in kerosene, which sounds crazy, but to be dousing kerosene to keep the bugs off of you.

It would be July, here you are with boots and a sweater going out to pick the blackberries. Then when you reached into the brambles, you're going to get pricked. To get the fruit was hard won. I think that it was the sweetness in our life that was unique. We would have blackberries, then probably ate a few bugs while we were picking them up, and then we'd go home and they'd get canned and they'd get washed. Then we would be able to have that taste of summer in the winter.

Alison Stewart: Hard-won too.

Crystal Wilkinson: Hard-won, yes.

Alison Stewart: You have a recipe for biscuits with blackberry soup, the praisesong biscuits, which you've been baking all your life. How would you describe what a praisesong biscuit tastes like?

Crystal Wilkinson: It tastes like heaven. There's been all of these controversies about why Northerners, no offense, can't make biscuits. [laughs]

Alison Stewart: It's not offensive if it's true.

Crystal Wilkinson: A lot of it has to do with the ingredients. I think having that soft flour that comes from my area and being able to make those biscuits and getting the knead right, don't over-knead it so that you have a nice soft, fluffy biscuit and not a brick.

Alison Stewart: Not a brick. In your research, what was a family story that surprised you that you hadn't really heard before?

Crystal Wilkinson: I think one of the stories that surprised me was when I found-- my grandmother was 14 when she got married. She got married on Christmas Eve. I knew that. The story came in me trying to-- I found an article where she'd been interviewed. They said, "What's your favorite Christmas present?" She didn't say, "My husband."

She talked about a little doll that her mother had made for her, and she talked about her mother's apple cake and how legendary it was, and how she hadn't been able to create it. That also led to me to think about her toil. She was 14. Of course, she was my grandmother, and I always knew she was 14, but for her to think about that doll made me think she was also thinking about her girlhood that was being lost by getting married at 14.

Alison Stewart: The name of the book is Praisesong for the Kitchen Ghosts: Stories and Recipes from Five Generations of Black Country Cooks. It is out now. Its author is Crystal Wilkinson. Crystal, thank you so much for joining us, sharing your recipes and your family's stories.

Crystal Wilkinson: Thank you for having me.

Copyright © 2024 New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.

New York Public Radio transcripts are created on a rush deadline, often by contractors. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of New York Public Radio’s programming is the audio record.