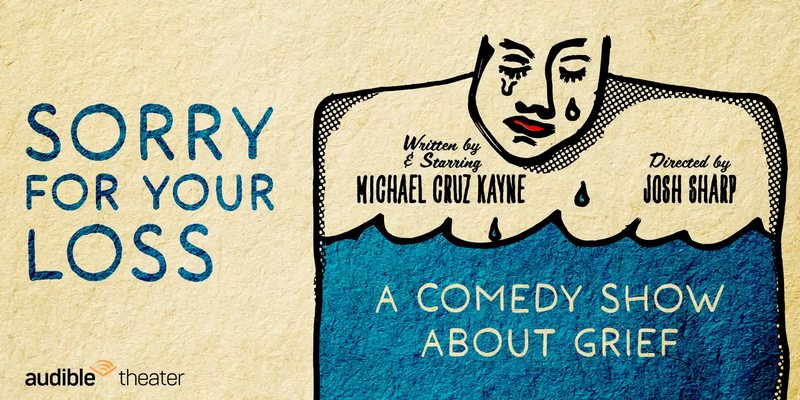

'Sorry For Your Loss:' A One-Person Comedy About The Death Of A Child

( Courtesy Minetta Lane Theatre )

[music]

Alison Stewart: This is All of It. I'm Alison Stewart live from the WNYC studios in Soho. Thank you for spending part of your day with us. Whether you're listening on the radio, live streaming or on demand, I am grateful you are here today. I'm also grateful to everybody who reached out about the end of MTV News. I appreciate you. I see you back. On the show today we'll speak to the star of a new movie Starling Girl as well as the film's writer and director, and we'll hear from newly anointed Pulitzer Prize-winning novelist Barbara Kingsolver. This hour we're going to be discussing life and death. Let's get this started with Michael Cruz Kayne and his comedic play show one man stand up it's all about loss.

[music]

At the top of his one-man show Sorry For Your Loss actor comic and writer for late night with Stephen Colbert, Michael Cruz Kayne warns you that you will probably laugh, but also likely cry and he is right. With candor and comedy, Michael introduces us to his family his whole family his awesome wife, Carrie, his children Truman, a ridiculously handsome teenager, his daughter Willa, a preteen with some Wednesday Adams energy, and Fisher who died when he was 34 days old. Fisher was born on October 15th, 2009, and after some complications quickly fell ill and died on November 18th, 2009. His twin Truman who I mentioned earlier survived.

Cruz's show can be traced back to a tweet around the 10th anniversary of Fisher's death. It was late in the evening on November 18th, 2019 and by the morning, that thread had gone viral. It began this way, "This isn't really what Twitter is for but 10 years ago today, my son died and I basically never talk about it with anyone other than my wife. It's taken me 10 years to realize that I want to talk about it all the time. This is about grief. Most of the conversations we've had about grieving are very, very weird. Tragedy is still so taboo, even in the era of the overshare. It's all very sorry for your loss and tilted heads and cards with calligraphy on them and whispering. We're all on tiptoes all the time."

Not anymore because that discussion of grief happens on stage in a show that shouldn't be funny but really kind of is. There are these hilarious and heartbreaking moments when you least expect them. It is called Sorry For Your Loss and as one reviewer said about Cruz Kayne, "Sorry For Your Loss is a great opportunity to get to know his unique voice and to laugh in the face of death even while recognizing that it will come for all of us. Michael Cruze Kayne is also the host of the podcast Good Cry and he joins us now in studio. Thank you for coming in.

Michael: Hey, thank you for having me. What a lovely introduction.

Alison Stewart: I'm glad you liked it. I very much enjoyed your show even though it made me all weepy and I had mascara raccoon eyes after.

Michael: Thank you. Raccoon eyes is a great compliment.

Alison Stewart: You know what, you should have a photo booth for people.

Michael: We should have or at least makeup wipes.

Alison Stewart: Makeup wipes that would be good. Listeners, let's get you in on this conversation. How have you dealt with grief? Is there something that worked for you that you want to share with your fellow public radio listeners? What do you think we as a culture have to learn about talking about grief? Why do we have a hard time talking about death and grief? Our phone lines are open, 212-433-9692, 212-433-WNYC or maybe you have seen Michael's show or listened to his podcast and have a question for him, our phone lines are open. 212-433-9692, 212-433-WNYC or you can hit us up on social media @AllOfItWNYC. In the days leading up to that tweet, Michael, had you been thinking about this anniversary and what you wanted to do?

Michael: Every year on the anniversary of his death, I would write something and put that just wherever. It was a place for my friends and family to access it so they'd keep up with both our living kids and how we were feeling about Fisher and also in a way to pay tribute to him. Yes, I'm thinking about him all the time. I would write a little post on Facebook or Tumblr or Blogspot or whatever and then on the 10-year anniversary, I wrote these tweets.

Alison Stewart: It's interesting because they were late at night these tweets.

Michael: Yes. That's right.

Alison Stewart: Had it been an all-day sort of energy inside of you like what am I going to do? How am I going to do this?

Michael: It is one of those things where I didn't get a tattoo or build a monument to him or something. This was the thing that I would do every year. There is a preciousness of poring over what it is you're going to say. Then it gets to be midnight almost and you're like oh boy, I got to write this before the day itself has passed.

Alison Stewart: You go to bed. You talk about the show and you wake up in the morning and this tweet has gone viral. People are really, really responding to it. What was something that was universal about the responses?

Michael: I would say, they were all very nice, even the people who said things that I don't super love. People saying, everything happens for a reason, those kinds of platitudes, even then that's just somebody trying to be nice. Then the other thing that bound up a lot of the other responses was that they were horrific. It became a thread where people shared a bunch of really horrible things that had happened to them. As awful as that sounds, it also was very freeing for a lot of people because they were able to talk about stuff that they had kept inside for however long.

Alison Stewart: Yes, somebody tweeted that it was a beautiful and helpful thread, they found it. Was it helpful for you to write?

Michael: It was helpful for me to write. It's always helpful for me to write and think and talk about Fisher but it was extremely helpful for me to get all those responses because it changed my whole feeling about the world. It felt like, my wife and I were the only two people who had really ever really felt this in any meaningful way. To be opened up to a whole community of people who had grieved was life-changing.

Alison Stewart: In the show you talk about how we don't like to talk about death. People have difficulty talking about death and grief. There's a sort of like, get over it movement. What do you think is behind the get over it movement?

Michael: Get over it, like, put it in the past and be fine?

Alison Stewart: Yes. You talk about you get this email from human resources that's like, move on.

Michael: I can't speak for every place in the world but at least I think where you and I live, there's a bunch of obsessions that come together to create this problem. One is, I don't want to sound like a political activist, but capitalism Which is, I know something bad has happened to you but we have to make these plastic forks so if you get back into the factory and make forks, we would really love it. Then the other one is an obsession with being beautiful and young all the time and always being happy. So much of social media is a highlight reel of the best moments in every person's life. If something terrible has happened to you, every image and tweet and Facebook post that you see makes you feel like that bad thing that has happened is totally alien to everybody else. You're the only person who has felt this way before.

Alison Stewart: When you talk about platitudes, what is the problem with platitudes?

Michael: The first time you hear any of them, it always feels nice I think. It's the 100th time that you're like, oh, this isn't someone talking to me. This is someone reciting something that they saw some place else and it makes you feel detached from reality. The first person who says sorry for your loss, thank you, I appreciate that, and the second person, but by the 100th person, you're like, "I wish you would say something real to me."

I know I'm different than most people because I'm a comedian but just as an example of that, a friend that I hadn't seen in a while came to the show recently and after the show she was very complimentary. I asked her about her family. I'm like, "How are your kids?" She goes, "They're alive and that's great." I think that it was a shocking thing to say but it also felt like such a real obvious thought that a person would have that I was like, "Oh, we can have an actual conversation about this now, which I appreciate."

Alison Stewart: That's also someone who feels really comfortable with you.

Michael: Yes.

Alison Stewart: Really, really comfortable with you. Let's take some calls. Let's talk to Mike from Brooklyn. Oh, hi, Mike.

Mike: Hi, thanks for taking my call and thanks for doing this segment. It's invaluable especially as we come out of the official declaration of the end of I don't even know what it is, the end of COVID supposedly. Thinking about it collectively and thinking about it politically, I have no problem with that. We have been compelled by capitalism to show up to places where epidemiologically which I never thought I would have to learn about and everybody else has or should have that it just brings you closer to what we want to avoid [unintelligible 00:09:31] pain of getting kicked out of your house. Thinking about it collectively [unintelligible 00:09:38]

Michael: We've got a second caller.

Alison Stewart: Mike, I think somebody wants some food so I'm going to let you go deal with that. Let's talk to William from New Jersey, on line one. Can we do that? William's coming on line one. William.

Michael: Come on, William. Show us the William.

Alison Stewart: My guest is Michael Cruz Kayne. The name of the show is Sorry For Your Loss. Let's see. Technology, did it work? Hi, William.

William: Hey, how are you? Can you hear me?

Alison Stewart: Yes, you're on the air.

William: Oh, excellent, okay. I'm really intrigued by this conversation, and I wanted to know your thoughts on somebody that's never really experienced grief to an intense degree like loss in the elderly or whatever it is, but also balancing that with knowing that it's inevitable. It's a part of life. What are your thoughts on that? Is it something that I should walk around waiting for the shoe to drop or? [unintelligible 00:10:36] to your thoughts?

Michael: Well, I don't think you should walk around waiting for the shoe to drop, and totally non-morbidly shoes will for sure drop. There will be shoes dropping. I think one of the ways that we can help each other with grief is just to be conscious of the idea that death is a thing that for sure is going to happen. The more that we can be true to each other and be honest about how we feel about that and not put it off, I think the better that is for everyone.

I think at some point in your life, you recognize that things-- Even when you're a kid, you crumple up a piece of paper, and then you unfold it, and it's always crumpled forever. There's a part of your brain that goes, "Oh, wait, some things never go back." I think that the whole rest of your life, you're trying to process that information. The more that you come to terms with it, the easier it will eventually be for you and everybody.

Alison Stewart: Michael, as you were starting to develop the show and write this show, what conversations did you have with your wife without talking about stuff that's so personal?

Michael: That's a great question. The show is for everyone, but it's really for me. It's even more really for my wife and my kids. Their feedback on what feels true to them what feels-- Because I'm recounting things accurately, but even in doing that, as I'm sure listeners of this know, what you choose to put in and what you choose to leave out affects the perception of what was really true in that moment. I would say my wife is an uncredited author, for sure in the show. Her feedback on every aspect of it has been necessary, to say the least.

Alison Stewart: Because you're a comic and you are a comic writer and performer, is comedy so much about timing and about rhythm. What have you noticed about the rhythm that's necessary when dealing with something that's a little more serious?

Michael: Well, one of the things that is fun about this show is that while it is I suppose a play, I guess, I don't know. Is it a play? It's a comedy.

Alison Stewart: I go back and forth myself.

Michael: Is that we've allowed the performer which, by the way, is me to be free in the moment. The show is the show. If you come you will see all the aspects of it every time. Also, if someone laughs in a weird place, or there are times when I call for audience interaction, if that interaction is unusual, in some way, we will speak to it. There's an ability to exploit my mastery of timing in the moment. I can feel people the ups and downs of the audience as they move from laughter to tears. I can try to, I believe and this may not be true that you can unlock things if you can make people laugh a little bit. You can teach them to perceive things in a different way if you disarm them a little bit. That's the dance that I'm doing during the show.

Alison Stewart: Yes. There's some really interesting stagecraft that goes on because you change microphones.

Michael: Yes. Oh, she's astute.

Alison Stewart: You wore the head the Janet Jackson Ted Talk microphone, and then a mic stand comes out because you're in performance mode as a comic, and then you go handheld, and then it disappears. Tell us a little bit about the microphone action.

Michael: Oh, my God, Josh Sharp, who directed this is going to love this conversation, because it's something that we wrestled with for a while. The show exists in a few modes. One of them is pure stand-up. When we shift into that mode, we move from the headset Britney Spears rent microphone into the handheld, just to demarcate that we've entered a new area of the performance. Then when we leave that to go back into storytelling, I lose the microphone.

Alison Stewart: Let's take a call. Let's talk to Sarah calling in from Brooklyn. Hi, Sarah. Thanks for calling All Of It.

Sarah: Hi. Thanks for taking my call. I was just calling in to say that I think for me, having recently lost a close loved one [unintelligible 00:15:06] that's the first time that I've experienced that one of the harder things to grapple with and to talk to people about is the existential dimension of it, and how it's not only pain and loss and grief that you're feeling, but you're also from my personal experience, there's a shift in how you see the world and your life and learning about impermanence, and how to make that part of your day to day life in the way that you see the world, as opposed to just being shell shocked when you get hit with that all of a sudden when you lose someone. I think that's something that's been particularly challenging for me.

Alison Stewart: Sarah, thank you for calling in. Michael, you're smiling. Is that resonating with you?

Michael: Well, yes. I relate to that so much. There's so many aspects of it that strike a chord with me. I think one thing that she didn't say explicitly, but I imagine is part of this is when she talks about impermanence, it's just that you explore concepts of death after someone you love has died in a way that you never would have before. I found so much talking to people who I think of as rigidly logical that when someone they love has died, their absolute certainty about returning to nothingness or whatever that they used to have, is obliterated for so many of these people that they're like, "You know what? I know this sounds--" I'm remembering that I can't swear, "I know this sounds--"

Alison Stewart: Whoo whoo.

Michael: Yes. Whoo whoo. Very good. Excellent work. I think that the red-tailed Robin that sits by the park bench when I go to the park, I think that's my sister. I think these pennies that I find heads up around the house, that is my dad telling me something. Before I had experienced tragedy, I think I would have been like, "That's all nonsense." I understand why you need that, but that's not real. Afterwards, I've just become way more open to the idea that the things that you imbue with meaning have meaning because you have given it to them, and that's enough. It doesn't need to be examined from a rational scientific point of view.

Alison Stewart: Let's talk to Helen, who's also in Brooklyn. Hi, Helen. Thanks for calling All Of It. You're on the air.

Helen: Oh, thank you so much. I'm glad that you picked up one of my call. First of all, I just want to say how moved I am. I'm in my garden while I'm listening via my iPhone to this program. To have explored this loss, and that board itself is a euphemism, but it's the least euphemistic word that we use. Because you didn't lose your son as though you lost a package [chuckles] somewhere. It is a loss to your life because your son isn't there. All you have are your memories and your connection to that initial event.

My loss was very different in that it was a part of a large public event that was front page news many years ago, and still has such political importance that if there's an update in that case, it became a legal case, it will be back in the news again. What that created was an instant group of people who if they wanted to come together, were able to and share that loss together. That's not always possible when it's very private. However, what is always true is that if you have friends and family who are there for you, it starts with just being there for you, from the moment that happens, and serving your needs. The first need is your presence. Then if there's anything practical you can do to ease their way.

Then the next thing always is listening, listening, and being there with your heart and your body. I was asked by a young man who was taking care of my child for an afternoon when I went off to one of our first group meetings, he said, "What can I do for you?" I said, "Just give me a hug." I needed physical warmth. I needed every aspect of what that hug means, which is I am here physically surrounding you with--

Alison Stewart: Helen, you know what, I'm going to dive in right there. Thank you so much for sharing your story and being so candid and open with us. My guest in the studio is Michael Cruz Kayne. The name of the show is Sorry for Your Loss. It's at the Minetta Lane Theater. It has just been extended, I understand.

Michael: It has indeed, brag.

Alison Stewart: Brag. We'll have more bragging and more of your calls after a quick break. This is all of it.

[music]

Alison Stewart: You are listening to All Of It on WNYC. I'm Alison Stewart. My guest this hour in the studio is Michael Cruz Kayne. The name of his show is Sorry for Your Loss at the Minetta Lane Theater. It has just been extended. I do want to talk a little bit about the comedy. The night I saw you made a very saucy joke about your parents and they were there.

[laughter]

What was that like and what was the conversation afterward?

Michael: My parents are to their great credit or possibly detriment, 100% supportive of everything I've ever done and said even if it's about them. We haven't talked about it that much. I wonder if they're saving it for a big family dinner where they say, "Everybody, get in here. We want to talk about the jokes Michael's been making in his show." [laughs] It's always been fun doing comedy in front of my parents.

Alison Stewart: In the show. It's a very simple staging. We do get to see some pictures. We get to see pictures of all of your kids. You saved some images and I don't want to give anything away because I want people to go see the show, but there's an unfortunate receipt that is part of this show. I'm going to leave it there. Why did you keep those things?

Michael: Once we knew that Fisher was going to die, I think we kept everything from that moment on. There's a box within a basket beside our bed at home that contains all kinds of souvenirs from that time, and I will periodically just open up and go through them, things that he wore at the hospital or whatever. I know this might be [laughs] too deeply sad, but the onesie that he would wear, I will sometimes open that box up and be like, "I'm just going to smell this onesie real quick. I don't remember what your question was, but that is the answer to it.

Alison Stewart: Why you kept things?

Michael: Yes. We just kept things because we wanted to be able to remember everything the best we possibly could, and we have not been able to, in spite of keeping everything. There's so many things where you go back and try and remember how something happened and the people who are there. Everything you're saying is wrong.

Alison Stewart: Let's talk to Adam from Queens. Hi, Adam. Thanks for calling All Of It.

Adam: Hi. Thanks for this conversation and for having me and Michael. My wife and I are really looking forward to seeing your show in the next couple of weeks. It was just recommended to us by another friend recently.

Michael: All right, thanks.

Adam: Wondering my wife had a stillbirth a couple of years ago and it felt like a very polarizing moment in our lives and our relationships with everyone around us, especially people we thought would be closest to us. I'm wondering what your experience was like with that and why do you think people's loss, especially when it comes to children is so almost threatening for lack of a better word, to a lot of people around the bereaved.

Michael: Can I just go or do you--

Alison Stewart: Yes, absolutely.

Michael: First of all, I love that question. I think it is because- I'm answering the second question first. I think the reason it's so threatening is that the idea that you will live to see your kids get to be whatever age is part of the founding documents of humanity. It's just like that is part of the world. Water is wet and you die before your kids. When that contract with the universe is broken or when you see that it could be broken, I think it totally ruins your concept of the world because then you're like, "Wait, what?" Maybe none of the other things that I thought are true.

I think it is really hard. Even now in my life, when someone finds out that my son has died, I can watch the information sometimes hit them in a way that even though this has happened to me, I am used to it and they're not. When they get that piece of information, it just totally obliterates them. There's no bringing them back. I have to just let you deal with what happened to me affects you. The other thing, I don't remember the first question exactly, but I did want to say just about stillbirth particularly that I have so many friends as does every adult who has had a stillbirth, a miscarriage.

I have so much empathy for what that is because it's a secret. It can happen and it's possible no one would ever know. You would just be carrying that around with you privately forever. I can't speak for everyone, but for me, carrying that around would be very painful if I couldn't share it. One of my [laughs] many particular failings is I can't not tell people things. If I weren't able to, I think that would just make me so sad.

Alison Stewart: Adam, thank you for calling in. Let's talk to Steven who's calling in from Dobbs Ferry. Hi, Steven. Thanks for calling All Of It.

Steven: Yes. Hi. Thank you. I would like to speak to one of the ways to deal with grief is to have other people recognize your child. We lost our son John, 12 years ago, and about two months after his death, his friends had a softball game, a memorial game. Subsequently, this went developed into a foundation, a nonprofit called the JCK Foundation after his initials. At 12 years now, we've gone to over 47 schools, helped children middle school and high school dealing with mental health challenges as my son had. It's very gratifying to see his friends help him and help us. One other thing I like to say is, that over time you find that your grief diminishes and you remember your child and sometimes you actually feel that it's a blessing that he's no longer suffering from his illness.

Alison Stewart: Steven, thank you so much for sharing. This is actually a nice segue into some of the talkbacks that you're doing with your show Sorry For Your Loss. I believe Experience Camps is one of the groups that you have coming in. Tell us a little bit about why you wanted this group. I know there's one tonight with Fay Saley, but why you wanted this group to come in, and what you've experienced during these talkbacks?

Michael: Experience Camps is a group that provides support for kids who have lost someone. I just wasn't even aware that someone would have thought to do that. I have, since I was very young, had an involvement with a camp called The Hole in the Wall Gang Camp, which is a camp for children with severe illness, which is not exactly what Experience Camp does, but my brother had cancer when he was younger, so I spent a lot of time with kids who are going through something brutal. I'm aware of the benefits that something like a camp where they can just be "normal" for summer can really change their whole lives.

That's one of the reasons I wanted to be involved with Experience Camps. The Talkbacks have been, we've only had one so far with Rebecca Sofer from Modern Loss, and it's been amazing. I'm very grateful for the people who come to the show, but also the callers to this program, People who have not only questions to ask but also insight and wisdom to share. It's been lovely.

Alison Stewart: You also host this podcast A Good Cry. You mentioned in the show that you like a good cry. Was that something that you learned from your parents? Was this something that has come to you out of maturity, out of therapy? When did you realize you were just a good crier?

Michael: I don't know. My parents are not big criers. I've rarely seen my dad cry. I don't think I've ever seen-- No, my mom cried once when we were watching Beaches. [laughs] I think what would happen for me was that I would have a moment in the day whether I was at work or wherever, where I would feel like I had to cry, but it's like don't cry, be a man, move on. Then I would find myself for the rest of the day being a jerk.

Or, my kids would do something totally benign and I would snap at them and I'm like, "What has turned me into this?" I came to the belief that it was because I had these negative feelings inside of me that I was bottling up and they were coming out in whatever other way because I wasn't letting them go out their natural path. Since then, if I have a moment where I do think I am going to cry,

I try to just be like, "Let's just do it. Let's just have a cry." Then at least physiologically, you will feel like you have exercised that part of you and you can carry on with your day.

You can have some forward motion after that, as opposed to being stuck in whatever that feeling is.

Alison Stewart: Can you hear audience members crying from stage?

Michael: Yes, sometimes I can hear audience members crying from the stage.

Alison Stewart: What does that do to you as a performer?

Michael: Not that differently from a laugh, I try to give it a space. I can tell that right now this has gotten to a place where you are extremely affected by it. Let's let that happen for a minute. Then when I feel like you are ready to move on to the next thought, then I'll take you to the next one.

Alison Stewart: Let's talk to Bill, who's calling in from Rockport, Massachusetts. Hey, Bill, thanks for calling All Of It.

Bill: Thank you for taking my call. I lost my first wife about nine years ago to a glioblastoma, and I don't know how the host felt, but for me-- He had his wife, and, of course, I can't imagine losing a child. I never had children, but we had an amazing life together. It felt like a trap door opened up. I lived in this small little house up in the woods at the time in northern Massachusetts, and it felt like I had fallen into this pit that I had so much trouble getting out of. I was so angry in the beginning, and as others have said, just the people that I thought were going to be there for me, it was like they could catch the cancer.

I had a lot of trouble with putting out a supposedly tight-knit family. Like, "Hey, we're here. She's still great. She's probably got six months left," and we were both in healthcare. We were both nurses, and it was just tremendously disappointing, but I just wanted to [unintelligible 00:32:13] as a guy the big gift I had I was 20 years sober in AA. I had a group of guys I sponsored for years had just swallowed me up and carried me along. Nine years later, my second wife is sober for 30 years, and we have an amazing life, and I'm so grateful. We live up in Rockport, which is an idyllic little town on the water.

Really to, hopefully, for guys, man, find people you can talk about it and people that all the euphemisms that were spoken of earlier. I would be so angry, but the thing I never did was [unintelligible 00:32:52] on anybody because people are so uncomfortable with it.

Alison Stewart: Bill, I'm going to dive in here. Bill's talking about support. We need to have people there who can support you.

Michael: Yes, and I think with any loss, it can feel difficult to find that support. I think having spoken to people who have lost parents and also lost children, I think again, the children thing can be specifically hard because like Bill said, people are like, "I'm afraid I'm going to catch the cancer from talking to you about it." I know that when I have a friend who says that they're pregnant and they ask me for advice about stuff, there is a part of me that's like, "Do you want to know about the real bad stuff right now or do you want--" It is hard to navigate that still, in spite of the love and support that I felt from people.

Alison Stewart: Evelyn tweeted to us, "Great show. I lost my husband in March and having never lost someone so close to me, I'm struggling with grief, when to move on, and how to see a future without him. Thank you for this." Our next guest is the curator of an exhibit called Death is Not the End, which is in Chelsea, and it's about how art in Christianity and Tibet Buddhism, how it examines death and life. There are four questions you can answer at the end. I'm going to pose one of them to you. You can pick one. It says describe your perfect afterlife. How does believing or not believing in the afterlife impact how you live? Tell us how death might not be the end. What is rebirth to you?

Michael: Oh, man, I want to do all of them. The one that I feel like I have an answer for that is somewhat already articulated is how death is not the end. I used to do a monologue in college when I was trying to be a musical theater performer. It was from a play called I Never Sang for My Father. I hope I'm saying this correctly because it speaks to me still many years later, even though I am, of course, incredibly young. The playwright says death ends a life, but it does not end a relationship which struggles on in the survivor's mind towards some resolution, which it never finds.

I think about that all the time. When I used to do that monologue, that was a bleak, deeply sad thought, but the further I get away from Fisher's death, the fact that I have not "resolved" it is sweet to me. It used to be days on end of just falling to the ground and crying. Now, years later, if I have a moment where something reminds me of him and it feels melancholy enough to make me cry, I welcome that. It feels like I'm in touch with a feeling that I don't want to forget.

Alison Stewart: Sorry For Your Loss is at the Minetta Lane Theater. It has been extended through June 10th I believe.

Michael: You got it.

Alison Stewart: Michael Cruz Kayne has been our guest. Thanks to everybody who called in and shared their stories and, Michael, thanks for coming to the studio. I know it's because you all are on strike, so I'm sorry about that.

Michael Cruz Kane: Power to the Union.

Alison Stewart: This is All Of It.

Copyright © 2023 New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.

New York Public Radio transcripts are created on a rush deadline, often by contractors. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of New York Public Radio’s programming is the audio record.