Smithsonian Folkways Turns 75

Alison: This is All Of It on WNYC. I'm Alison Stewart. We just had a preview of this year's Brooklyn Folk Festival. We wanted to note the festival will help celebrate the 75th anniversary of an important folk-forward record label that started right here in New York City and has released timeless recordings from artists like Leadbelly, Woody Guthrie, and Pete Seeger.

MUSIC - Trini Lopez: If I Had a Hammer

If I had a hammer

I'd hammer in the morning

I'd hammer in the evening

All over this land

I'd hammer out danger

I'd hammer out a warning

I'd hammer out love between

My brothers and my sisters, ah-ah

All over this land

If I had a bell

I'd ring it in the morning

Folkways Records was founded in 1948 and incorporated by the Smithsonian in the 1980s with a mission to document music and sounds from all over the country and the world. It's focus on preservation has included, not just songs by artists whose names you know, but also field recordings of folklore, and traditional music, and even the sounds of nature and city streets. As part of its 75th anniversary celebrations, joining me now is the Folkways director and curator, Maureen Loughran. I got all tangled up in my words. Maureen, thank you for coming in. You got see that in real life.

Maureen: [laughs]

Alison: The glitch in the machine. Also, joining us is Jake Blount, Folkways signee and an acclaimed singer, songwriter, and banjo player, and a rising scholar of folk and African-American music. Hi, Jake. Nice to meet you.

Jake: You too. Thanks for having me.

Alison: Smithsonian Folkways Recordings began right here in New York. Who founded it, Maureen, and why? What was the original focus?

Maureen: Yes, so Folkways, as you said, was founded in 1948 here in New York City, and the founder was Moses Asch. Really, what Mo was up to was trying to document musics from all over the place. It's what he called people's music.

Alison: Oh.

Maureen: A lot of people consider Smithsonian Folkways as folk music, but we really are talking about music from all over the world, all kinds of people, and also all kinds of sounds.

Alison: A lot of histories tend to focus on Asch, fewer mention Distler. What were they doing beforehand? What do we need to know about them as people?

Maureen: Well, Mo Asch started out as an audio engineer. He had a particular interest in the sound of things, and so from there started this label thinking that-- There were lots of opportunities for popular music at the time to have access to platforms, such as recorded sound, but there is lots of music out there that didn't have that same access. That was his intention, is really to provide a space for musics from all over the place to have a chance in the industry that they didn't have before.

Alison: Jake, I want to bring you in the conversation. You're from DC, you went to a school that has a really rich history. One of the first integrated schools in DC. The rumor was you played electric guitar in a rock band in high school.

Maureen: Yes, indeed.

Alison: Now, you're working towards your PhD in ethnomusicology at Brown. Whoop whoop, my alma mater.

Maureen: Yes.

Alison: Oh, you too?

Maureen: Oh, amazing.

Alison: Didn't know that. Ah. Conversation later. How did you end up making your way to acoustic and folk music?

Maureen: I had a lucky encounter with this wonderful band called Megan Jean and the KFB. I was in a Ethiopian restaurant down on U Street in Washington, DC. For some reason, there was an Americana Festival happening in town that included a stage in this Ethiopian restaurant. This duo got up with a washboard and a banjo, and started playing. I went up and talked to them after the show, and Megan and Byrne, is the banjo player's name, they told me about the history of the banjo, its connection to African-American culture, and specifically that of the Chesapeake Bay region, which is where my family is from, where my ancestors were held centuries ago.

It made me want to learn more about it, so I started digging in real deeply after that.

Alison: What appealed to you about folk music? You could have just gone and seen that, and said, "Oh, that was nice," and kept going.

Maureen: It's true. The irony is that I was on the way to a James Blake concert. I was there for dubstep because it was the early 2010s, and found this thing on the way. I think there were a few things that appealed to me about it. Of course, I was excited about hearing its connection to my family's history and the significance that it might have had to my forerunners, the way that their lives might have been structured around it.

At the same time, I think the modern culture of it just appealed to me, that these were just normal people who had devoted a ton of time to getting really good at what they did and were touring around the country in the back of their Honda Element, had no home address at the time, playing their heart out and playing these incredible songs. I think it was my first time being exposed to that culture of indie musicians, who maybe weren't getting the same big public display that a lot of the artists we typically hear about do, but are so devoted to their craft that they're willing to sacrifice that much for it.

Alison: Maureen, you have a PhD in ethnomusicology, and you came to Folkways after working on the music radio show, American Routes, that was out of New Orleans, right?

Maureen: New Orleans, yes.

Alison: Before you joined Folkways, and you were working in that same orbit and universe, what did the label mean to you?

Maureen: Folkways is really foundational in the kind of work that I do. As you said, I came to this as a radio producer, so I'm more used to being on the other side of that glass, but the kind of music that we explored in American Routes, the show down there, was essentially the Folkways catalog. All of the traditions of the United States exploring who we are through sound, who we say we are as Americans through the music that we play. Folkways really does a really great job of presenting that to everybody, and providing access to it.

One of the great things about Folkways is you can get on the website, you can listen to the music, you can download our liner notes for free and learn so much about who we are.

Alison: Jake, what's something that an artist, a creative person, can do through folk music that is different than what you can do in other genres?

Jake: I think it provides you an opportunity to step out of your own shoes a little bit and connect to something that's bigger than yourself. I am someone who, I've only performed traditional repertoire really in my professional career. I think that's partly because it makes it easier for me to stand up for the communities that I feel like I'm a part of and the causes that I believe in without making myself the center of attention, which I think is what a lot of artists sometimes struggle with. Knowing how to speak to those things without making those things about you.

I think being able to dig into the history to go back and learn a tune from 100, 200, 300 years ago, and tell the story that went alongside it. Let's me bring people in, put people in those folks' shoes rather than mine. I think it connects us in a much more extensive web than maybe we would have otherwise.

Alison: Let's listen to a little bit of your work. You released the album, The New Faith, last year. Let's listen to a track from it. Here is Didn't It Rain from Jake Blount.

MUSIC - Jake Blount: Didn't It Rain

Didn't it rain, children

Oh yes, didn't it (Didn't it?)

You know it did (Didn't it?)

Didn't it, woah my lord

Didn't it rain

Well, it rained 40 days, it rained 40 nights

Wasn't no land nowhere in sight

God sent the raven to spread the news

Hoist his wings and away he flew

To the east, to the west, north to the south

All day, all night, how it rained, how it rained

Tell me, didn't it rain, a-rain, a-rain, children

Rain, oh my lord

Didn't it (Didn't it?)

You know it did (Didn't it?)

Didn't it, woah my lord

Didn't it rain

Knock at the window, knock at the door

Crying brother, can't you take a couple more

Brother said, well, your wallet looks a little thin

Alison: That's Jake Blount, Didn't It Rain, from the album, The New Faith. We are discussing Smithsonian Folkways Recordings. It's the 25th anniversary of Smithsonian Folkways. My guests are Maureen Loughran, studio director and curator of Smithsonian Folkways Recordings; and Jake Blount, musician and a Folkways artist. When you are focused on, Maureen, curating, as in your job, when you think about the modern mission of Folkways, we heard about its history, when you think about going forward, what are some of your considerations when you think about the mission?

Maureen: Well, I'm really glad we just listened to Jake because what he's doing in his music is pointing the forward direction for Folkways. He's really diving deep into the traditions that are represented on the label. That's music that can be already heard on Folkways, but he's taking it in a future direction and he's showing that tradition is evolving. It's not a static thing. It's always the contributions of those who come into it, and change it, and have a future for it.

I think that the kinds of considerations that we're taking when we're curating the collection, is thinking about where's the trician going? Where's the music going? How can we find spaces for people to explore these traditions?

Alison: Alexander has called in he wants to add to the conversation. Hi, Alexander, calling in from Queens. You're on the air.

Alexander: Hi, thank you, Alison. I really appreciate it. I also have a PhD in ethnomusicology, and I did my research in the '90s. At the time, this was before people had access to all kinds of music from all around the world through the internet and Spotify. The only way that I could get access to the limited number of recordings that featured the music of the people that I was interested in, who are the Akan people of Ghana, was really through Folkways and a few other limited outlets. It made a huge difference not only for my research on that specific area, but just to be able to get access to music from the United States and from around the world.

For someone like me, who's also really interested in the relationship between music of Africa and the African diaspora, Folkways was also invaluable because of the storehouse of music that it has from those areas. The only way to understand those relationships is to hear the music. I had to go to Ghana, in West Africa to study the music I was interested in. That's expensive. It costs a lot of money. It takes a lot of effort. Not everybody can do it, but most people could get access to those Folkways recordings, and they're fantastic. Thank you.

Alison: Alexander, thanks for calling in. I'm going to Ghana in a few months. Very excited. I might have put a hold music on my itinerary.

Maureen: We might have to send you a playlist.

Alison: Would you?

Maureen: Yes, of course.

Alison: My guests are Maureen Loughran, director and curator of Smithsonian Folkways recordings; and Jake Blount musician and Folkways artists. We're going to talk more about the 75th anniversary and hear more of Jake's music after a quick break. This is All Of It. This is All Of It on WNYC. I'm Alison Stewart. My guests are artists Jake Blount, as well as Maureen Loughran. She is director and curator of Smithsonian Folkways recordings. He is a musician and a Folkways artist. It is the 75th anniversary of Smithsonian Folkways Recordings.

I want to play some more of your music, Jake. We're listening to another track from The New Faith. This is Death Have Mercy and we can hear hip hop influence in this when you think about where hip hop and bluegrass and folk recordings intersect. How and why did they go together?

Jake: Well, I've always had this funny piece of dialogue with with folk musicians who maybe have a more conservative definition of what folk music is. In the time and place where I grew up in Washington DC, there certainly was fiddle and banjo music of varying stripes going on around me but it wasn't what most people did. When I think about the folk music that was around me, it might have been like go-go getting played outside the Chinatown metro stop or like a dude with some bucket drums on the street or my friends having a cipher or whatever.

It's all part of the same collage to me, and I think that maybe the only reason why we perceive these musics as being so different is because they've been chopped up into an easily marketable format so many times. I'm not sure that the boxes we've been sold necessarily represent the whole of what was going on back then or what's going on today.

Alison: Let's hear Death Have Mercy from The New Faith by Jake Blount.

MUSIC - Jake Blount: Death Have Mercy

Whoa, death, have mercy

Hah, death, have mercy

Oh, death, have mercy

Spare me over another year

Fallen in you like I resolve something new

Like I belong in dispute

Proof in the pudding, balance in my footing

I stood where I could, now I'm falling for you

Coulda sawed me in two pieces

Heart on my sleeve and the blood coulda drew leeches

You a fantasy, and one I plan to keep

Drawing lines in the sand that'll reach between two beaches

I'm sure of it, walking hand in hand

Makin' a plan to go and get to the core of it

My heart's iron-solid, you make ore of it

My entire mind and body for sure toughened

You gotta love it

Have mercy on me, I don't know more's coming

I can't force it, you lord above it

Praise you, I of course covet

Implore you to bring another morning, I'm mourning

Those who never knew you, nor them still wishing you'd ignore them

Hoping I'd be more important

Alison: Jake, who are were hearing on this track?

Jake: That's my friend Demeanor. Real name Justin Harrington. He's an incredible rapper from Greensboro, North Carolina and been on the road with Rhiannon Giddens these past few months, and he's going to be joining my band for our tour in January. Super excited to spend more time with him. He's a banjo player, a bones player, a rapper, someone who already understood all of the pieces I was trying to draw together. There was no one better suited for this project.

Alison: Got a text from someone saying, "Very important record liberation folk music from Latin America, from Folkways Recordings." This is a tough question, what is one of your favorite Folkways Recordings, Maureen?

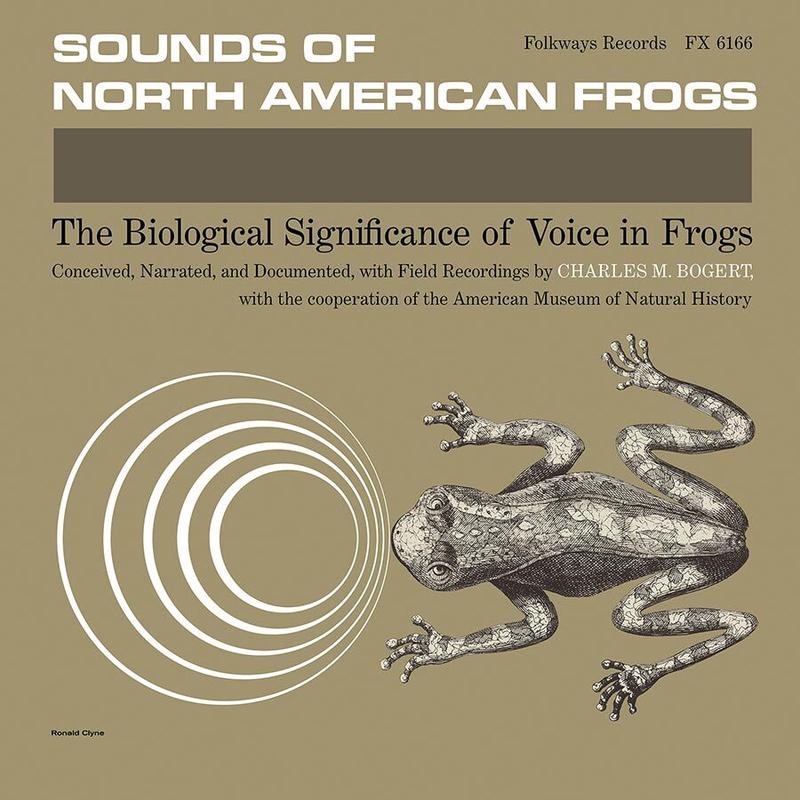

Maureen: It's so hard. It's the hardest question I always get, but I get it a lot. What I'll say is that one of the most interesting records that we have that we just actually rereleased on LP for the first time since 1958, is the sound of North American Frogs, which people think, "Well, wait, what was it doing in Folkways?" What we have in our catalog is a whole collection of sounds. It's not just music, it sounds of the environment, sounds of people, sounds of the office, and this just happens to be sounds of frogs. It's an underground hit. For some reason, lots and lots of people love this record.

Alison: Of course, you pulled some of the frog tracks.

Maureen: We have to.

Alison: Let's listen.

Charles: As many as 200 or 300 voices may be heard in a single pond in parts of southern Florida, where the barking frog breeds along with other tree frogs, toads and frogs. A barking tree frog is easily recognizable, and of course, recorded in Highlands County Florida, even though 10 other species of frogs were crawling at the same time.

[background sounds]

Alison: Who was that we heard on the front?

Maureen: That's Charles Bogart, who was a biologist and was one of the first biologists to actually use a tape recorder in the field. That's what also makes this recording pretty landmark, but I can imagine it being remixed I was listening for that. There's potential there. I dare someone to go do that.

Alison: Jake, what is a selection are from the Folkways catalogue that you really like or you go back to a regularly?

Jake: I think the one that I've come back to the most often is probably songs my mother taught me. Fannie Lou Hamer. That's my favorite one.

Alison: Can I play one of my favorite ones?

Maureen: Of course.

Alison: It's a little bit of a ring, only because it's a friend of mine since college and she was nominated for a Grammy for this. Let's listen to Liz Mitchell from the children's album Little Bird with Woody Guthrie's Who's My Pretty Baby.

MUSIC - Woody Guthrie: Who's My Pretty Baby

Who's my pretty baby?

Who's my pretty little baby?

You're my pretty little baby,

Hey hey, pretty babe

Hey hey, pretty baby,

Ho ho, pretty little baby

Ha ha, pretty babe

You're my pretty little baby,

Hey hey, pretty babe

Who'll be my little man?

Who'll be my nice lady?

Who'll be my funny little buddy?

Hey hey, pretty babe

You''ll be my little man

You'll be my nice lady

You'll be my funny little bunny

Hey hey, pretty babe

Alison: Thank you for indulging me. I just think she's got a beautiful voice.

Maureen: Oh, no, I love that record. What's great about that, too, is that that just shows you how much children's music is a really important part of our catalogue, and in fact, one of our most important children's artists, Ella Jenkins is going to turn 100 next year.

Alison: Oh my gosh.

Maureen: Knowing that she's a part of our catalog is just so special and I'm glad that you played that.

Alison: Could you talk to us a little bit about the role of archivists?

Maureen: Sure. Part of what we have as our collection is this 75 years' worth of material that we steward and make sure is available to the public. Archivists are part of that, making sure that not only we have access to the old copy, the art, the liner notes, the audio, but just knowing the history of how all of these projects were made. One of the great things about Folkways is it's not just the music on the disc. It's the liner notes. It's the art. It's all of it because it contributes to how we understand what it is that we're hearing, the context. It's really important.

Alison: It's all of it. My guest is Maureen Loughran. She's director and curator of Smithsonian Folkways Recordings. Also, joining us is Jake Blount, a musician and Folkways artist. Jake, you've used nonmusical sounds in your recordings. What interests you about that?

Jake: Well, I think part of the task of any folk musician is always paying respect to the context of the music in addition to just playing the songs themselves. Of course, we talk about that a lot on a metaphorical level, maybe a cultural level. You think about the political things that were going on, the historical events that informed the music that you're playing. You also have to think about the literal place that the music came from. I think Steven Feld is the guy who comes to mind for me in terms of really bringing that to the fore in thinking about how certain types of songs that might be sung in certain places or at certain times of day operate in concert with the natural world around them.

That these aren't two separate things, that we become part of the sound of the landscape. I think for me, in my recorded work, it's been important to bring a little bit of that back because especially the new faith, which is this Afrofuturist work, I am building a world. The world needs to be present in the sound. Otherwise, it's just a narrative, and there is no world, there is no immersion to be had. It felt really important to me in that respect. I think a lot of other musicians have taken on some of the same ideas.

Alison: You just use the word Afrofuturist. Sometimes people don't like certain labels but I heard you use it. You're okay with that? You feel good about that?

Jake: I'm excited about it.

Alison: Tell me why.

Jake: I grew up loving sci-fi and fantasy. It's always been my thing. I've always had a lot more trouble with sci-fi because it purports to represent the future, or a future a lot of the time, and there are never brown people there. I'm like, "What does that say about what happened between then and now that in the future everybody's white?" It made me really uncomfortable and made it feel like that genre wasn't accessible to me a lot of the time. Reading Octavia Butler, reading especially NK Jemisin, who's my favorite author, made me want to dip my toe in and think a little bit about what the future might look like for us and for our music.

I think it felt important to me because so many of the people who have written powerfully and eloquently on Black music, like Samuel A Floyd, I think is my favorite example, talks about how the way that Black music making works is by channeling these people who came before you, that it's not just you singing. You can hear the line of people that that song came down through. I've always really respected that idea. I think the benefit of Afrofuturism is that it displaces you in that chain of transmission so that rather than just the mouthpiece, you also become the person who's 3, 4, 5, 10 steps behind in the chain of transmission.

It legitimizes your own perspective. I think that can be a really helpful way to form an original take on folk music when so often you can get caught up in traditionalism, rigidity, and recreating what's been made before.

Alison: Folkways will be celebrated at Brooklyn Folk Fest this weekend. What can festival goers expect?

Maureen: Well, we have some concerts that are happening on Friday. It starts at 7:00 PM. Sonia Sanchez will be there.

Alison: Oh, wow.

Maureen: Al Stewart, who we heard earlier in the Hour. Charlie Parr, who's a current Folkways artist, performing. There's more concerts on Saturday, a panel discussion about folkways history on Saturday afternoon.

Alison: Oh, my gosh.

Maureen: It's a jam packed.

Alison: Wow.

Maureen: But I really hope everybody has a chance to come out and visit with us and learn more about Folkways.

Alison: I've got a text that says, "My favorite Smithsonian artist would be Elizabeth Mitchell," another brown grad, and my daughter. Yay, Smithsonian. Liz Mitchell's mom's listening. Hi, mom. Before we go, in our last minute, I did want to ask you, Jake, about your new super group, New Dangerfield. Tell us a little bit about it in a minute.

Jake: All right. It is a brand new Black string band comprised of myself, Kaia Kater, Tray Wellington, and Nelson Williams. Really wonderful, top-notch musicians making some really exciting music. Again, trying to balance original contributions and real respect for tradition and rigorous traditional performance in that string band repertoire, paying some homage to our heroes and teachers, The Carolina Chocolate Drops as we go.

Alison: My guests have been Jake Blount, musician and Folkways artist; and Maureen Loughran, director and curator of Smithsonian Folkways Recording. Happy anniversary.

Maureen: Thank you.

Alison: Have a great time at Brooklyn Fest. Nice to meet you, Jake.

Jake: Nice to meet you, too. Thanks for having me.

Alison: There is more All Of It on the way. Performer and Bronx native Shari Lewis always came with a plus one, her concert companion, the sock puppet, Lamb Chop. She was a groundbreaker on television at just 24 years old. A new documentary talks about how she changed the face of children's television. We'll talk to the director of Shari and Lamb Chop. That's the next hour.

Copyright © 2023 New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.

New York Public Radio transcripts are created on a rush deadline, often by contractors. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of New York Public Radio’s programming is the audio record.