Rosa Parks' Lifelong Activism

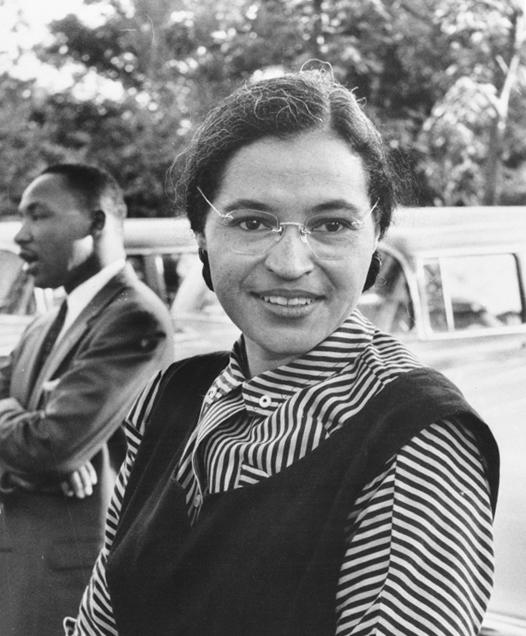

( Ebony Magazine/National Archives / Wikimedia Commons )

[music]

Alison Stewart: This is All Of It. I'm Alison Stewart. We're following our conversation about Shirley Chisholm with a contemporary of Chisholm's in more ways than one, Rosa Parks. When you see photos of them together, you realize how visual cues affect how we think about each woman. On the surface, they seem really different, but the reality is they were similar in one important way. They were both mavericks. Most people know that about Chisholm. Park's fierce independence streak has been written out of history until recently. The woman described as a demure seamstress who was too tired to give up her seat on a bus was a civil rights strategist long before that ride in 1955.

Later in her life, she became a Black Panther supporter. She was also the victim of sexism within the Civil Rights movement and endured economic hardship because of it. Her story is being told in the documentary called The Rebellious Life of Mrs. Rosa Parks, based on a book of the same name, by Jeanne Theoharis, and co-directed by Yoruba Richen. Here is about a minute and a half from the top of the film, you'll hear an introduction then Mrs. Parks speaking at a post-Selma March event when police went after protestors and you'll hear a few words from historians and a family member.

Speaker 2: The First Lady of the Movement, Mrs. Rosa Parks, raise your hand.

Rosa Parks: Rev. Abernathy and all of my brothers and sisters and my children, because I have been called the mother of this. We are not in a struggle of Black against white, but wrong and right.

Speaker 4: Rosa Parks is arguably one of the most celebrated Americans of the 20th century, and arguably, one of the most distorted and misunderstood.

Rosa: You see before you now a victim of all that has been perpetrated against one to make us less than human.

Speaker 5: Yes, we all understand that she went and sat down on the bus. The narrow narrative of her just on one day did something. We need to dispel that.

Rosa: I am handicapped in every way, but I am expected to be a first-class citizen. I want to be one. Of course, last few days in Selma, actually, I almost lost the faith. I said to myself, "I could not come here seeing what had happened in Selma, I'm only in love."

Speaker 6: If they could see her talking about the Republic of New Africa, if they could see her out there with the Panthers in Oakland, if they could see her in all of these fragrant varieties of her personality, then they would understand the real Rosa Parks but they might have been just a little bit frightened.

Alison: The film screen at Tribeca and is now available on Peacock. Yoruba Richen co-directed the film and served as an executive producer. I interviewed her last week at a live event and thought the film was so interesting. I wanted to share it with all of you, my listeners, this Women's History Month. It's nice to see you again, Yoruba.

Yoruba Richen: Great to see you, Alison.

Alison Stewart: Yoruba, she worked in the Civil Rights Movement a long time before 1955. What first drew her to work in civil rights?

Yoruba: I think it was her experience. Her experience of a Black woman growing up in Alabama in the early 1900s. We start the film pretty early on when she tells one of her first memories of sitting with her grandfather on the porch of their house as he is warding off the KKK with a gun, and how she wanted to see him defend her family and shoot that gun. I think that is the basis of her fight and of why she became a civil rights Black freedom struggle activist.

She also had a father who was, though he was very light skin, almost could pass for white, he did not take anything from white people. He stood up for himself and a mother who instilled self-worth. I think it was that family how she grew up that instilled who she was going to be as a fighter.

Alison: Why do we have this image of her as this mild demure seamstress, too tired to move rather than this fighter, this fire-brand?

Yoruba: I think one thing is the sexism around our understanding of the Black freedom struggle. Only recently have we started to uncover the crucial work that Black women did in the movement. The other part of it is that her personality was quiet and not boastful. One person in the film says her strength was in her quietness. I think that was part of it. Then also, too, in terms of being reduced just to the tired woman on the bus, she was never asked by the media anything else but about that moment.

Even though she was working in Detroit in the second part of her life in Detroit in the 1960s as the world was blowing up in John Conyers' office at the height of Black power and Black militancy, she was only asked about that moment. I think it's those factors that led to this misreading and misunderstanding of who she was.

Alison: What impact did that have on you as a filmmaker having to figure out how to tell the story, given to your point, the media never asked her about anything else?

Yoruba: Luckily, and it's how we came to the film, we had the great book by Jeanne Theoharis, who had done an extensive amount of work on Rosa Parks, her life, her family, and her colleagues, and comrades. We had that as a base. That allowed us to not only see what were the stories that we wanted to tell in order to paint this portrait of her and her work but who to talk to, where archives were. We decided to take the approach that we wanted Mrs. Parks to lead us through the film.

Her voice. We wanted her voice to be the center. Not only just her on video or news or audio but her words because she has a lot of letters. We bring that to life as well. I had somebody just tell me at a screening couple of days ago, they were like, "Wow, I've never really heard her speak." That, to me, is so important that we bring that to the viewers.

Alison: My guest, Yoruba Richen, the name of the film is The Rebellious Life of Mrs. Rosa Parks. You can watch it now on Peacock. Parks knew this about herself because she'd been working in the civil rights movement that she was the right person at the right time. Another young woman had been in a similar situation, but they were doing respectability politics at that time with who would get to represent the movement. There was colorism at play with that young woman as well. Why did Rosa say, "Yes," to being used as a test case because they asked her really after?

Yoruba: I think it's important to understand that there were many women and many people who had confrontations on the bus. That's one thing that I learned in making this film. It'd been a long-standing place of conflict for Black people who were trying to go to work, go to school, what have you, and were made to move for a white person. The indignity around that was really prevalent in the Black community. It had been a longstanding thing. There had been women, especially women who had taken a stand before. You mentioned Claudette Colvin, who was the young woman who had refused to give up her seat a few months before Rosa Parks.

I think, as you said, there was an idea of we have to have a model plaintiff. Claudette Colvin was young. She was dark skin. She was feisty as well. They did not choose to have her as the model case in this instance. Rosa Parks had also confronted bus drivers before. This wasn't the first time. She was ready. Also, she was ready, she was ready for the fight. You also have to remember, Emmett Till had just happened. We tell her stories of her struggles to vote and to get voting rights. This was a woman who had been fighting for her own rights and was also quite frustrated with the slow pace of how things were going.

Brown v Board had just come down and she was frustrated with Montgomery's Black elite that she felt were going too slow. This was the moment for her that she felt it was time to take a stand and to get the ball rolling on integration in Montgomery.

Alison: You can learn so much in this film. One of the things I never knew was-- and you go through the actual moment that for her to get up, four other people would've had to stand up as well. I don't know why that detail sticks in my mind, but it really changes the dynamic of it.

Yoruba: It's so ridiculous. [chuckles].

Alison: It's so ridiculous, yes.

Yoruba: Absolutely. Often, we say people think it's, "Oh, she had to move to the back of the bus." That's also the understanding. No, there was a very ridiculous complexity in how segregation worked on the buses. I found that fascinating too.

Alison: She was in a seat that Black people could sit in unless a white person wanted it.

Yoruba: It was no man's land.

Alison: There's another part of the film, which is heartbreaking, and it's really important to go into, is the idea that after this incident and after the bus boycott and she becomes a mother of the civil rights movement, Rosa Parks and her husband, really fall in tough economic times, you have a tax return from 1959 where they only meet $700 one year. One, why was she struggling so financially, and why was she left to struggle?

Yoruba: It is really heartbreaking. Well, during the boycott, she lost her job. She was fired. Her husband lost his job. We have to also remember there was massive resistance from white resistance to this. The bus boycott went on for more than a year. Then, afterwards, she was threatened. She was ostracized and she was not given any job by SCLC, the Southern Christian Leadership Council, Dr. King's organization.

He comes out of the boycott, as this is his coming-out party. She was not given a job. She had to move to Detroit, where she had family, because of the threats, and was in an economically precarious situation for many years until she got the job with Congressman Conyers. That was the first time she had healthcare, for example.

Alison: Wow. It's so amazing to think about Rosa Parks not being able to make her bills. We're talking about The Rebellious Life of Mrs. Rosa Parks. It's documentary now on Peacock. I'm speaking with its co-director and one of its executive producers, Yoruba Richen. This is something I asked you last week, but I think it's a really interesting question. You had a great answer. What are the challenges and what are the opportunities of making a film about someone who is iconic, it's an overused word, but she really is?

Yoruba: Well, there's so many opportunities with this one. When I read the book, that's how I got involved in the project. My co-director, Joanna Hamilton, came to me and said, "Did you know there's never been a feature film about Rosa Parks and read this book?" I read the book and I was amazed by all that I didn't know. I'm always intrigued when I don't know something that I think I should then I feel like it's an opportunity, then there's probably other people out there that didn't know it as well.

There's so much opportunity to take this name that people know and to really reveal and uncover and tell the story in a different way. There's always challenges with every film. The challenge is that with this one in particular, as I mentioned, she was always asked about the same thing. In terms of news footage or interviews, it was really like digging through and finding her talking about these other parts of her life, like her work on the [unintelligible 00:14:39] Taylor case, investigating sexual violence against Black women, which we found her talking about. That was one of the biggest challenges.

Alison: You can see it all, and you should watch this film, The Rebellious Life of Mrs. Rosa Parks. It is now on Peacock. I have been speaking with its co-director and an executive producer on the film, Yoruba Richen. Yoruba, thank you so much for being with us.

Yoruba: Thank you for having me.

Alison: On tomorrow's show, Author, Joseph Earl Thomas, he grew up in northeast Philly in an unstable environment, to get through his difficult childhood, he threw himself into the world of geek culture. His experiences are counted in his memoir sync, which the New York Times calls an extraordinary memoir of Black American boyhood. That is tomorrow. I'm Alison Stewart. I appreciate you listening and I appreciate you. I'll meet you back here next time.

[music]

Copyright © 2023 New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.

New York Public Radio transcripts are created on a rush deadline, often by contractors. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of New York Public Radio’s programming is the audio record.