Preserving NYC

( Courtesy of Village Preservation )

[All Of It intro music]

Alison Stewart: This is All Of It. I'm Alison Stewart live from the WNYC studios in SoHo. Thank you for spending part of your day with us. I'm grateful you're here. On today's show, I'll speak with author Katia Lief about her new novel, Invisible Woman. Actor Daryl McCormack joins me to discuss his role in the new Showtime series, The Woman in the Wall, it's very creepy, along with showrunner Joe Murtagh. The amazing blue singer Bettye LaVette joins us for listening party for her Grammy-nominated blues album. That is the plan so let's get this started with some New York City history.

[music]

When you walk around New York City it's easy to find history on every corner. Maybe you walk past Emma Lazarus's home on West 10th Street and you can imagine her thinking about her poem, The New Colossus, or strolling along Macken Street in Bed Stuy and imagine the families in the 19th-century wood frame houses. Preservation groups across the city work to protect meaningful structures and places, sometimes earning the ire of developers or even individual owners. My next guest has spent the past 20 years working to save historic parts of Greenwich Village. He wrote a meaningful piece about the stores Tory's 14th Street holds, wedge between Foot Locker and Dunkin Donuts.

Andrew Berman wrote, "Change in our city is inevitable, but too often the price for such change is the erasure of the histories of New Yorkers with the least power and privilege. The city's landmark Preservation Commission has the ability and the obligation to change that. The sights on and just off 14th Street along with others elsewhere across the five boroughs present a critical opportunity for them to do so. Now's the time for the city to act before it's too late."

One of the latest buildings his group is fighting for is one block south on 13th Street, and it has a rich history but many stakeholders. Joining us now to talk about the work he does and why is, Andrew Berman, Executive Director of Village Preservation. Welcome to the studio.

Andrew Berman: Thanks so much for having me.

Alison Stewart: We want to preface this conversation by noting that Village Preservation is an advocacy group and this isn't a conversation about right or wrong. We're really interested in what the group does, how it does it, and why. Listeners, we're going to open this up to all neighborhoods. What's the New York City landmark you love, and why? What would you like to see preserved in your neighborhood? Is there a building you think deserves landmark status? Maybe you want to share why you think it is or isn't a good move to landmark buildings.

Our number is 212-433-9692, 212-433-WNYC. You can call in. Join us on air. You can also text that number. Our social media is available as well @allofitwnyc. We're talking about history and landmarks in New York City right now. What is the goal of Village Preservation, Andrew?

Andrew Berman: Well, our mission is to document, celebrate, and preserve the special architectural and cultural heritage of Greenwich Village, the East Village in NoHo. That means everything from the historic buildings to the small businesses, the local cultural institutions. It's an incredibly rich history that covers everything from innovators to immigrants, civil rights advocates, to artists. It's really the story in many ways of not only New York but the country.

Alison Stewart: Why was there a need for a village preservation group when it started?

Andrew Berman: Sure. Well, we began in 1980, and as I think most people know, these neighborhoods are some of the oldest in our city very, very rich in history. They're also incredibly valuable real estate. A lot of people have ideas for things that should be done with them that are not necessarily consistent with preserving all of those important elements of that history.

Our group among others works to try to make sure that the most important parts of those neighborhoods are preserved, that they live on to tell those stories for another day. That means they get adaptively reused. Something that used to be a home becomes a theater. Something that used to be a school becomes offices for a design firm. A factory becomes a house of worship. That's part of what we think of as the cycle of virtue in preserving historic neighborhoods.

Alison Stewart: How has the group's mission and MO changed over the last 20 years?

Andrew Berman: Well, our geographic scope has expanded somewhat, originally, we were really focused on actually just a part of Greenwich Village, what was called the Greenwich Village, Historic District, still is. Now we include all of Greenwich Village as well as those two other neighborhoods. The scope of our work is definitely expanded beyond preserving historic buildings to, as I mentioned, other elements that really make up the character of these neighborhoods, the small businesses, the types of housing that we have, the types of local, cultural institutions, religious institutions, things of that nature, that really are what make a community what it is.

Alison Stewart: I'm curious about black swan events. We've had three in the past 20 years. 911, Superstorm Sandy, and COVID. I'm interested how each changed your work. Let's start with 911. How did it change what Village Preservation did and thought about doing?

Andrew Berman: Sure. Well, obviously, an event like 911 makes everybody think about what's important and why you exist. Neighborhoods like ours which were close to, not directly affected by 911, but certainly impacted by it, we lost a lot of friends and neighbors. Obviously, it was an incredibly traumatic event for those communities. One of the things that we've done in the interim is we've tried very hard to document and remember how people reacted to that. The various ways. The good, the bad, the ugly, the hurt, the sad, the mournful.

We have several collections in our historic image archive that people took at the time of what was happening on the ground. It's important that we remember that. Those are sometimes painful memories, but it's important that they not be erased.

Alison Stewart: How about for Superstorm Sandy?

Andrew Berman: Well, that certainly made us think a lot more about resiliency, and parts of our neighborhood were deeply affected. There were places like Westbeth or West Village houses, which were along the Hudson River waterfront, parts of them were uninhabitable for over a year. One of the things that we focused more on is the issue of resiliency and making sure that these buildings not only survive development schemes but just the impact of nature and climate change.

Alison Stewart: Maybe too recent, but COVID?

Andrew Berman: COVID, certainly, affected us a lot as well. I think one of the things that it's done is made us realize how precious and precarious a lot of our local businesses are. Many of them had such a tough time surviving COVID. We've given special attention to trying to help and support long-standing existing local, small, independent businesses, as well as giving a boost to new ones so that hopefully they can stay in the neighborhood.

Alison Stewart: My guest is Andrew Berman, Executive Director of Village Preservation. We're talking about landmarks and parts of neighborhoods that you really love, part of the history of your neighborhood that you really love. Let's take a few calls. Let's talk to Mark calling in from Manhattan. Good afternoon, Mark, you're on the air.

Mark: Hi, thank you. I appreciate your work, Andrew. I'm aware of it. I have been a tour guide and a historian in New York for 35 years. Landmarking is a very controversial subject, but more important is not just the buildings but the tenor of the areas around the buildings. You can see in other cities like say in Europe in Madrid, you can go for miles before you see modern buildings sticking up. Sightlines are just as important as the buildings themselves.

If you saw in the New York Times a month ago, the building going up on 5th Avenue just south of the Empire State Building destroyed a view that we cherished for 70 years of the Empire State Building and New York in general. We're losing a lot of the integrity of our skyline and of our neighborhoods on zoning planning. That seems to be happening all around. What are your thoughts about the protection beyond just the simple building, but of a neighborhood as we do sometimes? Also, have sightlines and areas that are considered to be in their own way landmarks just because they're not the building, they're the skyline.

Andrew Berman: Sure. Well, certainly, these are all important issues. All of this is about balancing the need for change, growth, development, and trying to both hold on to what's the most important parts of what we have and managing the growth in ways that feel as though it builds on the best of what we have, as opposed to just destroying and tearing it down. Landmarking is one small part of that. Something like 4% of the city is landmarked. It's a tiny fraction of our city for which that's really an appropriate response. Good zoning is enormously important. It shapes what can be built, how big it is, what's in it.

We also obviously need to do a lot of work to make sure that the city remains affordable and accessible, whether it's in terms of who can live here, types of businesses that can locate here. These are all things that I think need to be front of mind in our planning and too often are not.

Alison Stewart: Obviously, you've seen there was a New York Times Op-Ed, someone from the Op-Ed board saying, "I don't want to live in a museum. New York City can't be a museum of over-aggressive landmarking and protection keeps us from building affordable housing and keeps us from having the future of New York City." What was your response when you read that piece?

Andrew Berman: Well, a couple of things. One is, even landmarking which again applies to about 4% of the city certainly does not preserve the city in amber by any means. Our areas that are landmarked are some of our most dynamic neighborhoods. They do undergo incredible amounts of change where buildings that were originally used for one purpose are transformed to a new one. There's also an enormous amount of new construction, which actually does take place in landmark districts. People think, "If an area is landmarked, nothing can ever get built there." In our neighborhood alone, we've seen some of the largest buildings built in the history of the neighborhood under the regime of landmark designation.

I think that-- and in terms of the issue of affordability, interestingly, one of the biggest threats to affordable housing is it being demolished and destroyed. Landmark districts actually tend to have very large reservoirs of things like rent-regulated housing which while landmarking is by no means the way of preserving affordable housing, it's one more bulwark that helps to ensure that buildings that contain whether it's affordable housing or affordable commercial spaces for stores have a fighting chance to live on.

Alison Stewart: Let's talk to Angela from the West Village. Hi, Angela, you are on the air.

Angela: Hi. Hi. Thank you so much for taking my call. Hi, Andrew. I'm calling about Christopher Street between Waverly Place and Greenwich Ave. The houses that are in the middle of the block that run back to Gay Street where one of them was taken down and now the other two on Gay Street. Are they taking them down completely? Because I know this block is some of the oldest buildings in the village from the 1820s. I think that's pretty old [laughs] for the village.

Andrew Berman: It is. It is.

Alison Stewart: Let's see. Andrew, what do you know about-- Andrew-

Angela: Like those white houses where the puppy stores were, are those completely coming down, are they going to preserve any of them, and why were they allowed to do that?

Andrew Berman: Sure. Those buildings on Christopher Street, we're keeping a very close eye on them. They are supposed to be being repaired. They are among the oldest buildings in the neighborhood and New York City and they are part of a larger group of buildings on both Christopher and Gay Street, which were in a terrible state of disrepair, landmarked. One of them was brought down because of some illegal work that was done there. It's our intention to push the city to ensure that the building that was demolished is rebuilt in its prior form and that the buildings that are still there are repaired and restored and do not suffer the same fate.

Alison Stewart: We have a text, someone asking what citizens can do if they suspect that their community is the target of predatory development.

Andrew Berman: Well, among other things, you should certainly engage your local city council member. They are key in terms of development issues for local communities. Certainly your community board as well. Local block associations and civic groups play a really important role in this. We live in a democracy where every voice should count, but it doesn't always quite work out that way. When you're part of a larger group, that voice can get amplified and can certainly have more of an impact.

Alison Stewart: Got a question, and if you can't answer it, that's totally fine. It's an interesting question though. Let's talk to Craig from Riverdale who's calling in on line 6. Hi, Craig.

Craig: Hey. How you doing?

Alison Stewart: Doing great.

Craig: I'm just curious. There are a couple of iconic establishments. I don't even know if they're still in business. One I know is not. One is Delmonico's, one of the oldest restaurants in New York which has a very unique facade on a rounded corner street, and the other is Harry's at Hanover, a famous Wall Street bar. I don't know if they're both still in business, but what actually happens? Do the owners have to leave the facade if it turns into something else? They can't make them [unintelligible 00:13:44] empty the whole time. What actually happens to not change it? Also, silly side note, I'm sick of all these big glass buildings going up. We're starting to look like Houston.

Alison Stewart: [laughs] Craig, thanks for calling in.

Andrew Berman: Sure. The way it works in New York is we have a mechanism for preserving a building, which is called landmarking. We don't currently have a mechanism for preserving what are sometimes referred to as legacy businesses.

Alison Stewart: Interesting.

Andrew Berman: The business survives basically as long as the business is able to and the landlord, if the business doesn't own its building, is willing to let them stay there. Once the business is gone, there's nothing that preserves the facade of the business or anything like that unless it happens to be part of a landmarked building.

We and others certainly are working on looking at ways to do more to help those long-term businesses survive and make sure that they have a chance of remaining for future generations to be able to appreciate. It's a more complicated thing to do than a building. You can say this building must stand, but if the family has sold it, it's not making money anymore, it's much, much harder to require that a business stay around in perpetuity.

Alison Stewart: Andrew, what are the biggest obstacles to the work you do?

Andrew Berman: One of the biggest obstacles, of course, is just real estate pressure. There's often this desire for the quickest buck. It's certainly been shown that historic buildings in cities can be incredibly financially lucrative, but oftentimes it's a longer-term investment. It requires more work, more attention.

I would say there's also been an increasing lack of support from city government for things like preserving history. I think that there's been an artificial and inaccurate framing of preservation as somehow being counter to the need to keep our city affordable. I actually think the two can very much go hand in hand and are in fact quite compatible more often than not. Those are some of the kinds of things that we're up against.

Also sometimes, as you mentioned, with property owners. Some property owners, not all, can be very resistant partly because sometimes it's fear of the unknown, sometimes it's misinformation about what landmarking or preserving involves. Sometimes it's just, I don't want somebody telling me what I can do, but there are so many wonderful success stories about preserved historic buildings and how they've flourished in so many ways while being preserved or landmarked. We try to get the word of that out to people.

Alison Stewart: My guest is Andrew Berman, executive director of Village Preservation. Listeners, we're opening up this conversation. What's a New York City landmark you love in your neighborhood and why? What do you think deserves to be preserved in your neighborhood? Maybe you have a question about preservation. The number is 212-433-9692, 212-433-WNYC. You can call in and join us on air or text to us at that number.

After the break, we'll talk about what's going on at 50 West 13th Street, invite a super caller in who's been working on some preservation and has been working a little bit hand in hand with Andrew. We'll get to more of your questions, and we'll have more after a quick break. This is All Of It.

[music]

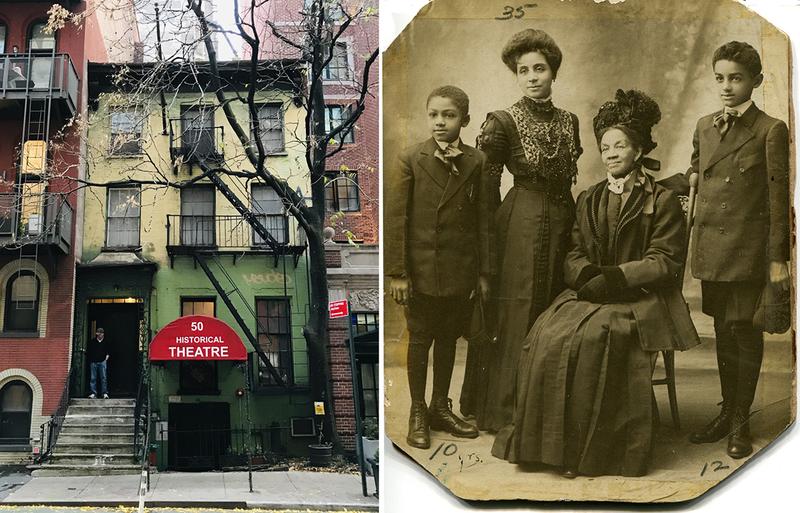

This is All Of It on WNYC. I'm Alison Stewart. My guest this hour is Andrew Berman, executive director of Village Preservation. We're talking about the work his group does and we're taking your calls as well. I want to ask you about 50 West 13th Street. This is a really interesting story and it's complicated in many ways. It used to house a well-known Off-Off Broadway stage, 13th Street Rep. The person who ran the company died at 103.

According to reporting in The Times, there have been struggles within the entities of the people who own shares of it, plus the building is in bad condition, but then, plus, it also has historic significance for the history of Black New Yorkers. Like I said, there's a lot of layers to this one building. Tell me who lived at 50 West 13th Street and why it is a building that your organization is taking an interest in.

Andrew Berman: Sure. As you said, it's the former home of the 13th Street Repertory Theater and it was built in the late 1840s, but from the late 1850s through the 1880s, it was the home of Jacob Day, which is a name that doesn't necessarily ring bells with too many people, but if you lived in 19th century New York, particularly if you were a Black New Yorker, it probably is a name you would have known. He was one of the city's most successful Black businessmen in the catering industry, which interestingly at the time was one of the few industries that was relatively open to Black New Yorkers and Americans.

He was also a civil rights advocate, an activist, very involved in the Abyssinian Baptist Church, which was at the time located in Greenwich Village. For listeners who don't know, at that time, Greenwich Village was actually the center of Black life in New York. It had the largest African American community in New York and Day was very actively involved with abolition efforts and then also, after abolition, with trying to remove discriminatory laws in New York that kept most Black men from actually being able to vote. There were different property requirements for Black men than for white men and, in fact, disenfranchised most Black men. He lived and had his business at this residence for about 30 years.

Alison Stewart: What is the status of the preservation campaign?

Andrew Berman: For about three years now we've actually been fighting to get the building landmarked. Its condition is deteriorating every day. The city's Landmarks Preservation Commission has not moved on it and they have not said that they will. In addition to Jacob Day, a somewhat more familiar name of somebody who we recently discovered through Eric Washington, lived there was Sarah Smith Garnet who is this iconic figure who was the first Black principal in the New York City school system. She founded the Equal Suffrage League, which was the first organization founded for Black women fighting for suffrage and so much more.

She lived there while it was owned by Jacob Day, who frequently would rent out rooms. It's unclear if he actually charged anything for it, mostly to widowers and teachers, all as far as we know, African American, probably people who are connected to the work that he did as a way of supporting them. She lived in this house for what seems to be maybe close to a decade.

Alison Stewart: Two things. One, I reached out to the Landmarks Commission via phone and email and I didn't hear back by the time we got on air. If they respond to me, we'll put it on our social media. I also want to bring in historian, Eric Washington. He spearheaded the preservation of one of the last standing schools for Black children in New York City at 128 West 17th Street. It was the location of Colored School No. 4. It was an important building block for the making of Harlem as a center for Black culture. We spoke to Eric when he first started this mission about two years ago. We asked him to call in to give us an update. Eric, thank you for calling in.

Eric Washington: Hi. Good morning. I mean good afternoon. Sorry.

Alison Stewart: Yes, good afternoon. Before we get to what's going on with Colored School No. 4, how did you come across this information about Sarah Garnet, and how did you get in contact with Village Preservation?

Eric Washington: I was working on a project that's related to Colored School No. 4. I'm trying to isolate some of the figures by figuring out their residential itinerary. Starting with Sarah Garnet, I was trying to pinpoint where she was between what period and what period. I'm going back to census records and back to records from the board of education and what have you. I actually had the census record for 1870 in my files, but I hadn't really zoned in on it, and this time I did, and I saw the name Jacob Day, and I thought, "I know that name." [chuckles]

I knew that there had been a struggle to get 50 West 13th Street landmarked and I shot Andrew a message attaching a copy of the census record and saying, "You might look at this. Will it have any bearing on the status of that building being landmarked?" It was by accident. I had it in my files, as I say, for a while, but I only just noticed it recently. Before she was Garnet, she was Sarah Tompkins when she was living there with one of her sisters, Emma Smith, and with her daughter, Serena Tompkins.

In the census, they have her daughter's name wrong as Selena, but it was Serena. From what I could tell so far, as Andrew said, for about 10 years, I'm seeing at least about 8 years that she was there from about 1865 to 1873, which is a substantial period of time.

Alison Stewart: Eric, I want to get people caught up. Colored School No. 4, which was at 128 West 17th Street. We talked about it on the air about two years ago. Remind folks how you stumbled across it because if somebody's walking down 17th Street, maybe they're going to housing works, I don't know. Maybe they're going to cafeteria for lunch. You wouldn't necessarily see it or pay attention to it. How did you come to discover it?

Eric Washington: I came to-- discovered it while doing research for my biography of a figure, James H. Williams, for a book [unintelligible 00:24:06] four years ago called Boss of the Grips: The Life of James H. Williams and the Red Caps of Grand Central Terminal. While trying to document every place where he lived or worked or went to school, that's how I learned that he'd gone to school on 17th Street.

With the help of public records like the tax photos at the Municipal Archives, I could see that the building-- what it looked like in 1940. Then I went down there on, I guess, it was 2018, I think it's the same building. [laughs] By cross-referencing a lot of public documents, I was convinced that this is the same building, it's still standing. At that time, I thought it was-- it went back to about 1870, and so I went with that, and that's because they changed the address at some point about, 1868.

The address used to be 98 West 17th Street, and then they changed it to 128. It actually gained another 20 years, so it was even older than I thought, which was already fairly impressive thinking that it was built circa 1870. It was built as we've learned 1849 to '50. This was the same case, as I understand, with the Jacob Day House. It used to be listed as 64 West 13th Street, and then about the same time, about 1868 or so, the address was reconfigured to 50 West 13th Street.

There was a lot of those changes of address going on about that. That's how I came upon the building.

Alison Stewart: It really caught the imagination of a lot of New Yorkers. You got a lot of press about this building, I think because people could go see it. They could see that it wasn't in the best state. People understood how important the history of Black Americans are for New York City. Once you got traction on this, there was a big day, May 23rd, 2023. What happened on that day?

Eric Washington: That was incredible. Thanks to a number of local groups including Andrew Berman's Village Preservation, people who wrote letters, particularly, Council Member Erik Bottcher's office, absolute neighbors, people who lived on the street next door signing petitions and talking about it. A bunch of us were there on that morning of May 23rd in front of the building because we understood it's going to be landmarked, and we listened to the countdown, if you will. That's when the Landmarks Preservation Commission designated it officially a landmark.

Plus, we were there with Mayor Adams who pledged that same morning in front of the school, $6 million toward the building's rehabilitation. It was a huge day. That news didn't come until 24 hours before, so it was an absolute surprise.

Alison Stewart: Eric, thank you so much for sharing your story from beginning to end. It's such an interesting way to think about how one person sees something, Andrew, and then does something about it. When you think about in your career your biggest win, or one that you'll be glad they write about you one day, "Andrew Berman helped this happen," what is it?

Andrew Berman: Probably, our efforts to get what we refer to as the South Village landmark, which is the part of Greenwich Village, basically South of Washington Square, Bleecker Street, MacDougal Street. A lot of people consider it the heart of the neighborhood but didn't realize that until relatively recently, it wasn't landmarked. It's got a particularly rich history in so many different ways. As I mentioned before, this was the part of Greenwich Village that was the heart of the African American community in the 19th century.

It was also the part of New York where there was the first ever concentrated area of LGBTQ establishment. It was the center of LGBTQ life in New York in the late 19th century. In the 20th century, it really was the center of the counterculture innovation, folk music, Dylan, Hendricks, everybody all here. That area had been left out of the landmarking of the 1960s, and in three successive waves, we were able to get that neighborhood landmarked in the 2000s.

Because of all that incredibly rich and previously overlooked history, immigrant history as well, I should say, they didn't focus on it in the 1960s because it was the more working-class part of the neighborhood, and we just thought that all of that history is actually not why it should be overlooked but why it should, in fact, be celebrated and preserved. Those designations, I think, are probably the ones I'm most proud of.

Alison Stewart: What's a loss? What was a loss that hurt?

Andrew Berman: It's funny, I always say this. There was a building called the Tunnel Garage, which believe it or not, was a parking garage, but it was built in the early 1920s. It was one of the city's very early first purpose-built parking garages. It was this gorgeous art deco structure that had a multicolored image of a Model T Ford emerging from the Holland Tunnel on the top of it. You could not imagine a more beautiful parking garage, and sadly, we lost the battle to save that from a developer. It's now condominiums.

Alison Stewart: We are going to go to Sarah on line six because a lot of people have questions about NYU.

Andrew Berman: Yes, great.

Alison Stewart: Sarah, go for it. You're on the air.

Sarah: [chuckles] Thank you. Hi. Thank you for all the work that you do. I'm actually calling about the Provincetown Playhouse and the Eugene O'Neill. I'm just wondering what exactly happened. I know that you worked very hard to try and save it and they said they would save part of the-- I think they said they would save the theater but it looks like only the facade in the front is used now. I just don't really understand it because I know it also belonged to the education department at NYU. I can take my answer off air. I just was curious about that.

Andrew Berman: The long and short is, unfortunately, it's another and a long line of broken promises by NYU. The Provincetown Playhouse which was really the birthplace of Off-Broadway theater in America. NYU was planning to demolish the entire building to build another law school building. We fought it. They offered as a compromise that the piece of the building that housed the black box of the theater would be preserved and they'd build around it.

We didn't love the compromise but it was what it was. Then behind construction fences, once work began we, discovered that they had actually demolished most of even the tiny portion of the building that they had said that they were going to preserve. Really what's still intact is just that small corner of the facade of the building, basically the entryway, and virtually all of the rest of it is gone.

Alison Stewart: We did get a text of someone saying that your archives are unheralded, that people should know more about the Village Preservation Archives. As we wrap, you want to share a little bit about them?

Andrew Berman: Sure. We have these incredible archives, photographs about 4,500 historic photographs, records of various organizations connected to the neighborhood, particularly preservation battles, oral histories with everyone from Jane Jacobs to Jonas Mekas, to a whole range of artists, business leaders, et cetera. Just go to our website, villagepreservation.org. It is literally a treasure trove of information that you could spend a day, a week, a year just exploring and that's what it's there for.

Alison Stewart: That's a good cold weather activity. [laughs]

Andrew Berman: Absolutely perfect today.

Alison Stewart: Andrew Berman is the Executive Director of Village Preservation. Thanks to everyone who called in and shared your thoughts and texted your thoughts. Thank you, Andrew, for coming to the studio.

Andrew Berman: Thanks for having me.

Copyright © 2024 New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.

New York Public Radio transcripts are created on a rush deadline, often by contractors. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of New York Public Radio’s programming is the audio record.