A New Zine Exhibit at Brooklyn Museum

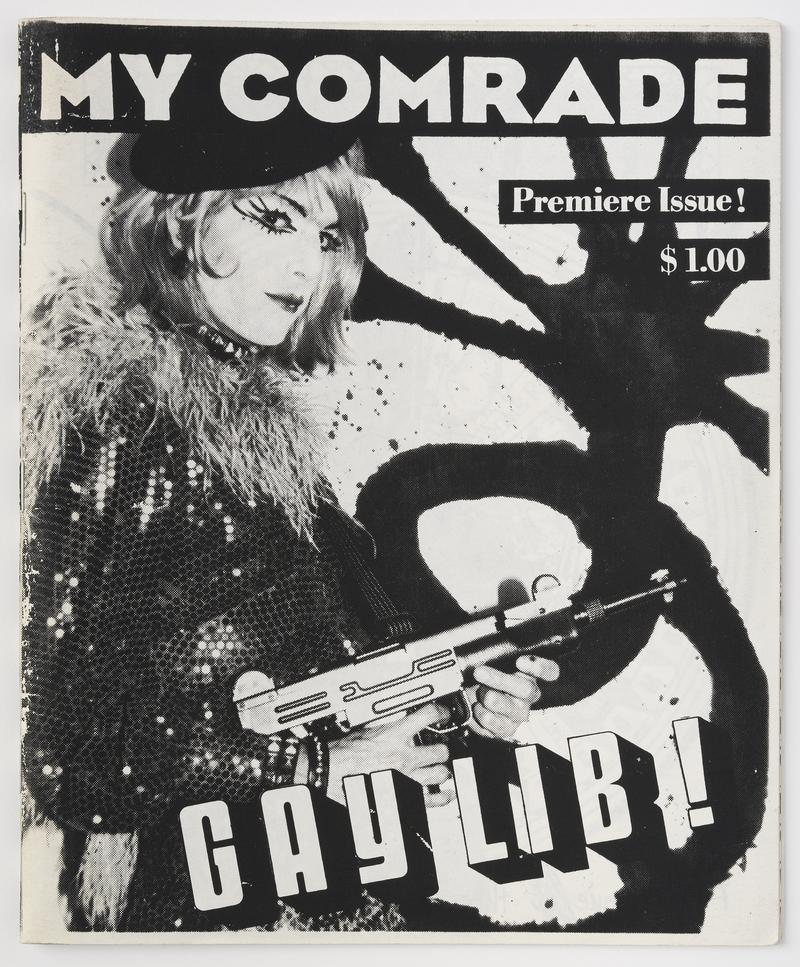

( Courtesy Brooklyn Museum, Evan McKnight )

[music]

Alison Stewart: This is All Of It on WNYC. I'm Alison Stewart. The Brooklyn Museum has a new exhibit opening today. It's called "Copy Machine Manifestos: Artists Who Make Zines." A zine, of course, is the shortened version of magazine, but zines are more than smaller versions of their corporate cousins. They're typically do-it-yourself endeavors, curated and crafted as acts of artistry themselves, as well as providing a platform for individual expression.

Listen to how zine artist Nyle G. Kim Kaliski frames his work. He says, "Paper and language are the two most essential tools for zine making, aside from a copier or a printer. It is really helpful for me to be surrounded physically by the material image in the liminal space of selecting and framing. It is as if the paper and I are having a tactile conversation. This conversation becomes the language of the zine, the content." The Brooklyn Museum's exhibit includes more than 800 images from the world of zines from the 1970s to today, broken out in categories like the punk explosion, critical promiscuity, something called subcultural topologies.

It is open now as of today, and you can catch it at the Brooklyn Museum until March, and this weekend, the museum is getting extra ziney because on Sunday, they're hosting a Zine Fair put on by the nonprofit publisher, Printed Matters, which will feature more than 60 zines and zine makers currently putting out work. Joining me now to talk about all of it, please welcome Branden Joseph, professor of modern and contemporary art at Columbia University and one of the contributing curators to the exhibit. Welcome to All Of It.

Branden Joseph: Thank you. Thanks for having me.

Alison Stewart: Listeners, give us a call to shout out the zines in your life, past and present. Maybe you are or used to be a zine maker or maybe you were a subscriber to a punk zine, or a queer or a feminist zine, or an art zine that made you feel like part of a community. Maybe you felt seen in a zine. Give us a call. 212-433-WNYC. 212-433-9692, you can call in, join us on the air, or you can text to us at that number, or you can tell us about it on our social media @AllOfItWNYC. Branden, we know what a pamphlet is, or a flier, or a brochure. What makes a zine a zine?

Branden Joseph: Historically, zines have been related, as you said at the opening, to magazines, but they've also been related to all of those publications, independent publications that you just mentioned, but also to what was known as the fanzine. We think of zines, and the zines in the exhibition are largely like this, as photocopied. The classic zine might be regular 8 1/2 by 11 paper, photocopied, stapled, fold into half and stapled. Zines actually begin in the 1930s, is in mimeograph form. They were the same, cheap, quick, ephemeral, and usually self-made publications, but they were related integrally to fan culture.

They started around science fiction fandom, they moved into comic book fandom, they ultimately, in the early '70s, moved into rock fandom, even before punk rock happens. There are fan communities that are interested in certain comics or certain types of music. Often, almost all the time, actually, part of the ethos of these fanzines is that they're very open to reader feedback and participation. They welcome correspondence, they welcome contributions, they welcome mentioning other types of zines. They're more open and collaborative with a community than your typical magazine that has a gatekeeper function of editors and others. They're really open to creating and fostering senses of community in that sense.

Alison Stewart: Some of the wall text explains that the earliest zines came out of something called male art networks. What was male art?

Branden Joseph: Yes. Our exhibition, the exhibition that Drew Sawyer and I put together is not all zines, of course, but it's zines particularly done by artists. The earliest zines in our exhibition are from-- well, the earliest is November '69, but basically from the '70s on. There was a group in the '70s that was national and international that was interested in correspondence art. They were interested in making things that were cheap and ephemeral, again, and that could be mailed to other people. It was also a sense of feedback.

You would mail your piece to someone, and they would mail you another piece, or maybe they would even take the piece you mailed to them and modify it and send it on to somebody else. The earliest artist zines that we chronicle in the exhibition are really ones that came out of these type of networks. For instance, there's one instance, which is in one case, actually, physical case, of a publication that was called the New York Correspondent School Weekly Breeder. It was a joke on weekly reader. It started as a one page mailer that was sent around. Then another person took it over. The first person was Ken [unintelligible 00:05:46] an artist. The next was Stu Horn, an artist in Philadelphia.

Stu Horn took that and made it a two-page mailer. Then it was passed on to a man named Tim Mancusi, a San Francisco artist. He made it into a full-fledged zine of 35 pages. Often these correspondence zines basically gathered mail that was sent to them, artists' mail that was sent to them, images, texts, et cetera, collated it, reproduced it, bound it often with just a staple and sometimes with just a paper clip, and then sent it out and distribute it to other people.

Not all correspondence art ended up in these little magazines. Some of the earliest artist zines that we chronicle come out of these distributed network communities that were really using the postal system as an alternative to the High Art Museum as a place to show and disseminate their work.

Alison Stewart: My guest is Branden Joseph, co-curator of "Copy Machine Manifestos: Artists Who Make Zines." It's at the Brooklyn Museum. It opens today. He's a professor of modern and contemporary art in the Department of Art, History, and Archeology at Columbia University. I do have to ask about manifestos.

Branden Joseph: Yes.

Alison Stewart: Why is that in the title?

Branden Joseph: The title, "Copy Machine Manifestos," was actually taken from an article that was published in the San Francisco Bay Guardian in the 1990s that was talking about the explosion of queer zines in the early 1990s. That was the title of the article. We liked it because, first of all, it foregrounds the copy machine, but second of all, many of these zines that we found over and over and over again. I just mentioned that correspondence art was an alternative to the High Art museum. Very often, the zine comes out of the people that want to take the means of production to get their voice told and against something that they perceive as anywhere from oppressive to just plain boring.

They want an alternative. Often, the zine contains manifestos in it. This is what we're doing. This is why we're doing it. Just as often, the zine itself acts as a manifesto in its form and in its content, whether it says this is a manifesto or not, it serves as a calling card, as advertisement, as a billboard of a particular person or a particular group's point of view. That artistic and activist dimension of zines, we like the way that the title foregrounded it, and of course, manifesto is something that if you're a card carrying art historian or frequent museum visitor, you know that manifestos are often associated with art movements.

It's a very art historical term too, while it's also an activist term. We like the way that it's switched between activism and art because that's exactly what these zines largely do.

Alison Stewart: Let's take a call. Jerry is calling from Nassau County. Jerry, thank you for calling WNYC. You're on the air.

Jerry: Thanks. Thanks for the trip down memory lane. I feel like I'm back in 1990. Do you have any copies of fact sheet five in your exhibition or any works by Ray Johnson, who was the godfather of mail art?

Branden Joseph: We don't have fact sheet five. We knew of fact sheet five, and that was a clearinghouse in itself, a network. It was a zine that actually allowed you to connect to other zines. We do have Ray Johnson. We have an original piece of Ray Johnson, original drawing by Ray Johnson that he submitted to the West Bay [unintelligible 00:09:51] which is one of the early correspondence zines. We have work by an artist, John Dowd, who was close to Ray Johnson, who made a collage in homage to, and was sent to Ray Johnson.

We did do research in Ray Johnson estate's archives too for this exhibition, and most of the artists in the first section, there's six sections in the exhibition, in the first section, were in male correspondence dialogue with Ray Johnson, so he was a very central figure.

Alison Stewart: Let's talk to Cliff, calling in from Manhattan. Cliff, thank you so much for calling All Of It.

Cliff: Well, thank you for the program. I'm involved in correspondence art, and in the '80s was involved in a zine called Secret Love, which was a gay male zine, and my question is, is Todd's copy center [unintelligible 00:10:54] Todd's copy shop mentioned in the exhibit? It was an enormously popular place for zine makers here in the '80s, I guess.

Branden Joseph: Yes, is it in Greenwich Village, west Village? I forget.

Cliff: Yes.

Alison Stewart: Yes.

Branden Joseph: Yes. It's not specifically mentioned, but artists did mention it and utilize it. Kate Hud, David [unintelligible 00:11:20] artists that are in the exhibition, I believe Kate Hud worked there. She worked at a coffee shop. I think it was that one. So, yes, the copy shop was itself a node of production and often of distribution as well. People would make their photocopy zines there and maybe leave them there. The record store was also not a site of production, but a node of distribution, certainly, even if your zine was not necessarily one that related to music. These sites are very important for the history of zines.

We chose to emphasize in the exhibition more these sites of distribution. For instance, we feature the Spew Festival, which happened two or three times and was one of the first queer zine conferences where people came together. We featured 1974 confluence of correspondence artists in Los Angeles called the Deca Dance, and which was a faux Hollywood style award show that happened in Los Angeles, was a couple years in the making where all these correspondence artists from Vancouver, New York, the Bay Area in San Francisco, Los Angeles, Toronto, all came together in this to stage this giant happening, which was as an award show, but it was also the first place that many of them met each other in person.

These moments where the virtual network becomes a real place of engagement is something that we foreground from the Deca Dance in '74 all the way to Devin Morris's Brown Paper Zine Fair in the 2000 and teens throughout the exhibition.

Alison Stewart: The publications are also eclectic and original, but can you pick out any connective tissue among the zines that come out of our area or out of Brooklyn and really have Brooklynese about them?

Branden Joseph: Well, there's a lot of-- the exhibition actually begins that first publication that I talked about, November '69, was done by John Dowd and Stanley Stellar. John Dowd lived in Park Slope. That was where his studio and home was. He worked at the Eagle Bar in the West Village. He was a graphic designer. He was a pop artist before that, and so he [unintelligible 00:13:56] which is what in the correspondence art network he called his studio, was located in Brooklyn. The exhibition begins in Brooklyn. We have an opening piece when you come in, which is by Yusef Hassan, Kwamé Sorrel of BlackMass Publishing in collaboration with Ari Marcopoulos and the musician, rapper and musician, Mike, AKA Dj Black Power, so all of them have Brooklyn connections and roots in the front of the exhibition.

When we get to the end, which is the last section, the sixth section of contemporary artists, many are also Brooklyn based, so Candace Williams, who just moved from Los Angeles to Brooklyn, Devin Morris, who had moved a couple years before from Baltimore to Brooklyn, Neta Bomani. I don't know if [unintelligible 00:14:49] Cruz lives in Brooklyn or not, but Pat McCarthy does, so we have a lot. There's a through line of Brooklyn that starts and ends the exhibition, but we also have Manhattan, Los Angeles, San Francisco, Chicago, Guadalajara, Mexico City, Toronto, Vancouver are all pretty important nodes throughout this exhibition.

Alison Stewart: As we said on Sunday, from 11:00 to 6:00 at the Brooklyn Museum. You can catch the Sunday Zine Fair put on by the non-profit Printed Matters. How would you describe the zine landscape today, given everything we've been talking about? We've got about a minute.

Branden Joseph: Zines are incredibly popular now, especially amongst artists, and they're just a way, I think, for artists, especially in sometimes burgeoning art market to be able to make work that can be bought cheaply, given away, that can have that community function and network function that people can take a zine or have a zine from an artist for $5, whereas maybe they can't buy a painting for the higher prices that there are, and really as we worked on this exhibition from 2019 to now, we really saw a wave of production. It's as popular now as it's ever been, and the Printed Matter zine Fair on Sunday is really going to feature that.

Alison Stewart: The name of the exhibit is "Copy Machine Manifestos" Artists who Make Zines." It's at the Brooklyn Museum, and it opened today. My guest has been Branden Joseph, professor at Columbia University, one of the co-curators. Thank you so much for joining us, and congratulations on the show.

Branden Joseph: Thank you for having me. It's been a pleasure.

Copyright © 2023 New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.

New York Public Radio transcripts are created on a rush deadline, often by contractors. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of New York Public Radio’s programming is the audio record.