Looking Back at Environmental Crisis Posters, 1970–2020

( Courtesy of Poster House )

[music]

Alison Stewart: This is All Of It on WNYC. I'm Alison Stewart. To follow up our previous conversation about green roofs, let's turn to how environmentalists have communicated the need to live sustainably. A new exhibition at Poster House is called, We Tried to Warn You! Environmental Crisis Posters, 1970–2020. There are 33 works spanning 50 years, and they're on view, including collages from Robert Rauschenberg and illustration by the late Great Milton Glaser who created the iconic I heart New York design. Just how much has changed about environmental messaging over the past five decades? Joining us now to talk about it, please welcome the exhibitions curator, Tim Medland. Tim, welcome to the studio.

Tim Medland: Thank you very much for having me.

Alison Stewart: For folks who don't know, Poster House is at 119 West 23rd Street, about a block and a half from the Flatiron Building. Listeners, if you want to get in on this conversation, we are interested in knowing what's something you remember seeing, a visual, a graphic that really made the climate crisis or other environmental issues hit home for you, 212-433-9692, 212-433-WNYC is our phone number. You can join us on air if you want to call in, or you can text to us at that number. Also, our social media's available @allofitwnyc. Tim, the exhibit is organized along four themes, earth, air, water and fire. Why that organizing structure?

Tim Medland: When I was first thinking about the show, I am a terrible, terrible nerd, I was reading so many books. One of the things that became obvious was we think about environmentalism as a modern-day thing, but actually there is not an ancient society, an ancient culture, an ancient religion that hasn't had environmentalism at their absolute core of their belief system. The four original elements were those four things. I thought, "Okay, rather than do a chronological order of a show, which would be the classic way of doing it, let's try respecting the elders."

Alison Stewart: [chuckles] Well said. When people started trying to communicate environmental messages, in this time period we're talking about '70 to 2020, what was consistent across culture and time?

Tim Medland: I think the early point was very much a respect for nature. Worried about environmental degradation, but we literally didn't know about existential threats at that point in time. It was very much focused on clean water, clean air, stuff that people could relate to and was easily measurable, I guess.

Alison Stewart: When you think about some of the themes over the timeline of the posters, there are gas masks and cars and plants and animals, how has the ask behind environmental posters changed over time? What it is they want the call to action?

Tim Medland: The early call to action was direct. I think it's worth noting, I tried to make a point of it right at the beginning of the show, we start with 1970 because it's the first Earth Day, and because it's the first Earth Day, and to put it into perspective, 20 million Americans participated in the first Earth Day. That's a 10th of the population at the time, give or take. We have a quote from Richard Nixon, as you walk in the door from his State of the Union address, NFB goes, "Richard Nixon, really?" I'm like, "Well, he was the president when the EPA came into being, when the Clean Air Act came into being."

Maybe he did or didn't believe in environmentalism, some of his advisors definitely did, surprisingly, but more to the point, 20 million Americans said, "We want you to notice this." There is not a politician on earth who I don't think will pay attention to that larger constituency. What then happened was people focused on, the clean air was the first real issue that everybody could understand because we had the smog issues, pollution coming out of your exhaust was disgusting, it was pre-catalytic converter. There were distinct issues to address.

Alison Stewart: You mentioned Earth Day, our caller on line one, Sarah from Bushwick has a memory of that. Hi, Sarah. Thank you for calling in.

Sarah: Hi. How are you doing? It's funny. I was thinking when you guys started talking that I guess I was in second grade and we had Earth Day and it was so exciting. Everybody got a cup with a tree in it and we all planted them, and it was every year we did that. There was Smokey the bear, talking about forest fire. I remember in our class, a teacher talking about littering how bad it was. It was kind of exciting when you were little. "Oh, yes. We can plant trees and keep clean, everything clean and pick up litter." They don't even do that now and it's so much worse. I don't get it. We were kids and it was great.

Alison Stewart: Sarah, thank you for calling in. That's an interesting point. At her point, it was great. Everybody was engaged and involved. What has that changed, and have posters addressed a change in attitudes?

Tim Medland: The messaging behind the posters has changed as we have come to-- Well, first the nature of the crisis has changed. To be clear, the fumes coming out of your exhaust are infinitely cleaner than they were 50 years ago. Situations have been addressed. It's just, overall, we're now dealing with the CO2 emissions, the climate change, the existential threats. One of the things the show addresses is corporate malfeasance, corporate duplicity and how we now know what's happened, so the more recent posters are very frequently angry because they're calling out those corporate actors.

Alison Stewart: It's a change in tone to match the times.

Tim Medland: It's a change in tone. What is interesting is, while we have the change in tone, though, I think the nature of this is it's been branded slow violence, and I think it's much harder for us all to deal with something that's that insidious and isn't visible on a day-to-day basis. Yes, we have orange skies in New York for three days, but it's not the 1.1 degree, 1.2 degree change, 1.3 degree, what does it actually mean? That, I think, is harder for posters to communicate and for us to actually deal with.

Alison Stewart: My guest is Tim Medland. He is a curator at Poster House of the, We Tried to Warn You! Environmental Crisis Posters, 1970–2020. There are some photographs from outer space that you cite as having changed the visual language of environmentalism, where after the Earthrise photo taken from the Apollo 8 mission, which has been called the most influential environmental photograph ever taken, how does it change how people think about climate change and see the planet Earth?

Tim Medland: Well, I think first of all, it led to a lot of posters that were produced with the earth on them. Those exist, and it's amazing how many different ways you can project exactly the same image if you want to. Skilled poster designers can do that. I think we became aware of how vulnerable we are. It was our only planet. Again, it was at that period of respecting nature. We're '60s, '70s, we are in the hippie era. That hippie imagery, the way I try and explain it is it lasts through till the early 90s, the sort of respect earth, love earth, love nature.

Alison Stewart: Hug a tree.

Tim Medland: Hug a tree and all very worthy stuff, before we then move to the specifics of within water, acid rain and rising ocean levels, we go through.

Alison Stewart: There's one poster that looks exactly like a Volkswagen ad except it says, "We're sorry that we got caught." What is that in reference to?

Tim Medland: This is by a group called Brandalism. It's designed by Jonathan Barnbrook, who's a famous British graphic designer. As you say, it looks exactly like a European Volkswagen poster. They are everywhere across Europe. This was produced in 2015 at the time of the Paris Accord. It also happened to be the time when a whistleblower had explained what the larger VW group had been doing with their diesel engines. Basically, when a new car goes to be tested by the EPA or another regulator, they're tested for exhaust emissions. Great. They go into test mode and they either come out clean or they need work. VW always tested very, very clean. That's great.

Alison Stewart: We know where this is going. [laughs]

Tim Medland: Unfortunately,-

Alison Stewart: They got caught.

Tim Medland: -if they were not in test mode, they were not clean. So far they've been fined $33 billion, and they're sorry they got caught. Again, it's that very direct naming and shaming, which is the new way of, I guess, the later posters.

Alison Stewart: Are there any intellectual property issues here?

Tim Medland: Yes. Cease and desist orders are bound.

Alison Stewart: Let's talk to Mitch from Westchester. Hi, Mitch, thanks for calling All Of It.

Mitch: Hey, how are you doing? Hi. This is a great program. Thank you.

Alison Stewart: You're on the air.

Mitch: Hi. My imagery that I remember because you were talking about icons was a image from the '60s of a man who was supposedly an American Indian crying over the condition of the Hudson River. I'm sure many people remember that. Maybe you want to tell us a little bit more because your production assistant filled me in a little bit.

Alison Stewart: Yes. We're going to get to that. Let's play a little bit of the ad. We actually pulled a little bit of that original ad as an alleged Native American man has been looking at trash on the ground, and then he's on the highway and somebody throws trash at his feet. Let's take a listen.

Iron Eyes Cody: Some people have a deep abiding respect for the natural beauty that was once this country. Some people don't. People start pollution, people can stop it.

Alison Stewart: What's the backstory on this?

Tim Medland: You need to understand this advert was aired in 1971. This is obviously pre-digital. It's physical film. It was so popular that TV stations had to go back and ask for more film because they were literally wearing through the film. We have a poster in the show, which is a steal from this film, with the logo, as he said, people start pollution, people can stop it. If you can imagine, for those who haven't seen it, the Native American paddling his canoe along this polluted river, and this terrible waste everywhere, cans, dead fish, smokestacks behind him, and then the camera zooms in and you see the tear roll down his cheek, and then he says the iconic thing.

The show has been open for a couple of weeks. My favorite thing is when I have two or three-generation groups come through. The older people remember this and say it was great because it taught me not to throw stuff in the river. I say, "It is great." Except Keep America Beautiful was a lobbying group for industry that was actively lobbying against regulation on themselves, it's the first greenwashing, trying to shift responsibility to individuals.

Alison Stewart: Wow.

Tim Medland: Of course, it's compounded now by the fact that the actor in question was actually an Italian. He'd been shot many times by John Wayne in various movies, but he was not Native American. Interestingly, only this year, Keep America Beautiful handed over the rights to the National Congress of the American Indian who have immediately withdrawn it saying it has always been inappropriate.

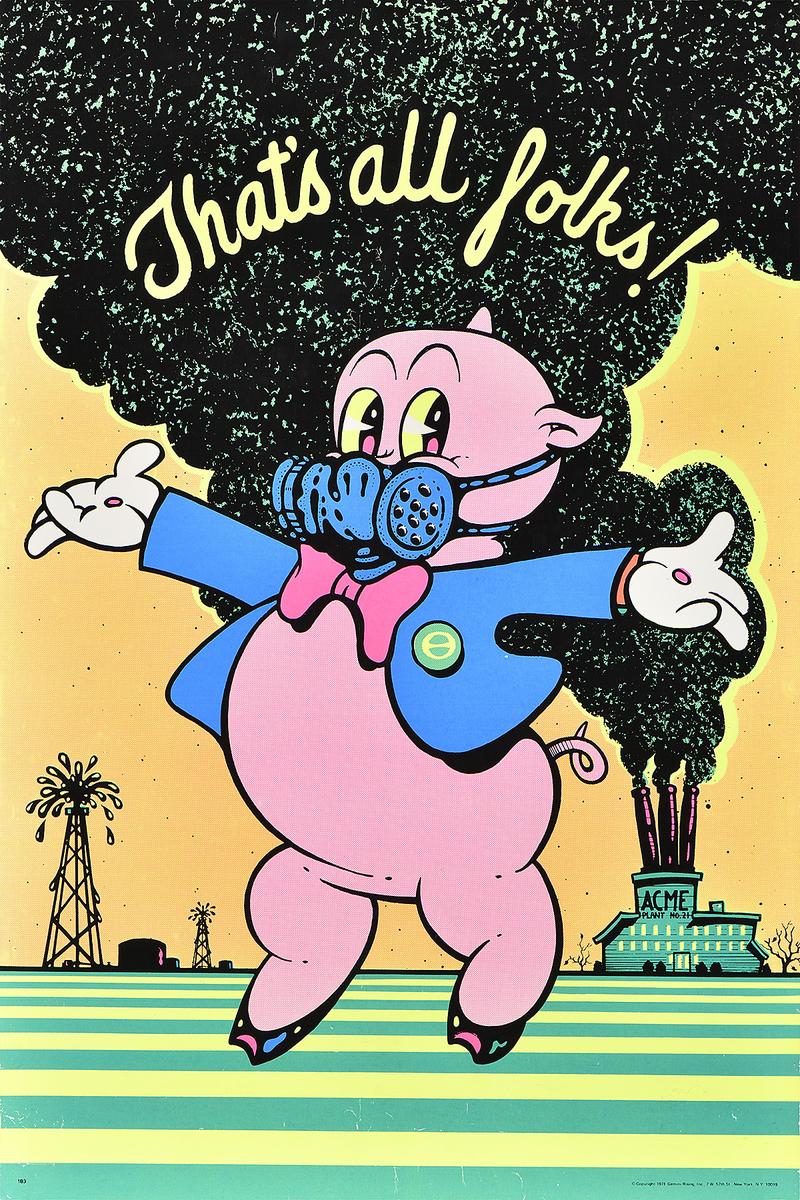

Alison Stewart: Some of the posters evoke image of childhood, Porky Pig with a gas mask. There's the Count von Count from Sesame Street telling a child, "The world is on track to be not one hotter, but ah, ah, ah, 2 degrees hotter." There's Eric Carle who wrote an illustrated The Very Hungry Caterpillar has a poster called For Every Child a Tree. How does this environmental messaging get at the idea of childhood? Why is it a good tool for persuasion?

Tim Medland: Ooh, that's a good question and not one I expected. I think children get it from a very young age. It's one of the things. It's like your caller came in, "Yes, I remember. It was exciting. Why would you not want to protect nature?" The imagery works for them. Yes, it's frequently from shows or books that they've already read. Also, for the adults, it brings in their inner child. It's actually interesting how many adults will go to the Eric Carle poster, just stand in front of it, and smile.

Alison Stewart: Oh, that's interesting. Of all the posters, which one, this is a little bit off of topic, do you think is the most aesthetically artistic?

Tim Medland: I'm going to change it. The one that strikes me as the most artistic is by Ernest Trova. It's from 1971. It's interesting because it's not the poster I wanted. There was a series of six posters produced by Olivetti to raise money for the UN environmental program in 1971. Ernest Trova was one of the artists. Roy Lichtenstein was one of them. Georgia O'Keeffe was another one. I thought, "Oh, yes, I'll have an O'Keeffe. I'll have a Lichtenstein. This is what I want." They weren't actually that good. Then I saw the Ernest Trova one and it's-- Ernest Trova is less well known now, but he was a sculptor. His most famous sculpture was called The Falling Man.

Alison Stewart: In about a minute, I just want to look.`

Tim Medland: Okay. That's a human leaning back into an uncertain future-

Alison Stewart: Oh.

Tim Medland: -and against an orange sky. Although it was in 1971, it seems incredibly prophetic. It's more abstract, but I really liked that.

Alison Stewart: We Tried to Warn You! Environmental Crisis Posters, 1970–2020 is at Poster House which is 119 West 23rd Street, about half a block from the Flatiron Building. I have been speaking with Tim Medland, independent curator with Poster House. Thank you so much for sharing your curation with us.

Tim Medland: Thank you very much for having me.

Alison Stewart: That is All Of It for today. I'm Alison Stewart. I appreciate you and I appreciate you listening and I'll meet you back here next time.

Copyright © 2023 New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.

New York Public Radio transcripts are created on a rush deadline, often by contractors. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of New York Public Radio’s programming is the audio record.