'I Heard It Through the Grapevine' and Baldwin's Centennial at Film Forum

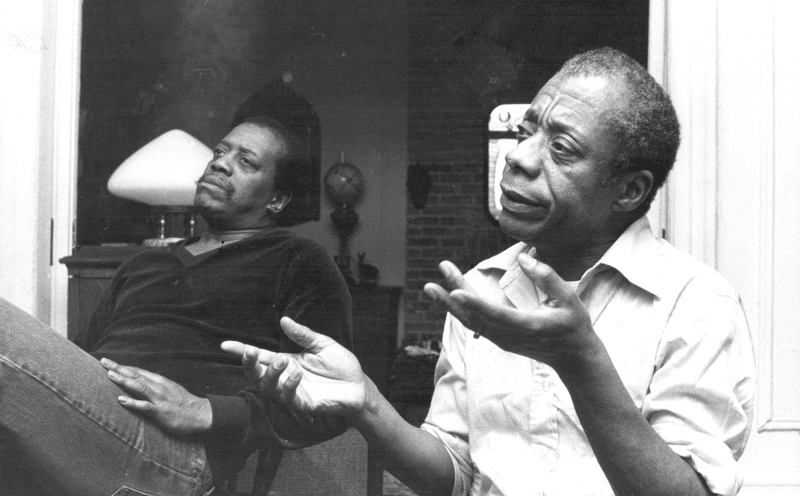

( Courtesy of Film Forum )

[MUSIC - Luscious Jackson: Citysong]

Alison: This is All Of It. I'm Alison Stewart, live from the WNYC Studios in SoHo. Thank you for spending part of your day with us, whether you're listening on the radio, live streaming, or on demand. I'm really grateful you're here. Later this hour, we'll discuss a new show featuring the work of Walasse Ting. The show focuses on his paintings that he made while working in New York City. Later on the week, we'll speak with Andrew Berman, who is leading the charge to preserve the cultural and architectural history of the West Village.

We'll talk about the New York Video Game Awards and why even if you aren't a gamer, you should know about them. You're going to have to tune in to find out. That is in our future but right now, in the present, we celebrate James Baldwin's centennial. 2024 marks the 100th birthday of writer and activist, James Baldwin, born in Harlem in August 1924. To celebrate, Film Forum is hosting a series of Baldwin-related documentary screenings, the first of which is a recently restored film directed by Dick Fontaine and Pat Hartley.

I Heard It Through the Grapevine follows Baldwin as an older man in 1980 as he embarks on a long journey throughout the South, his first time visiting the region since the civil rights movement. Let's listen to a clip from the opening of the film.

James Baldwin: It was 1957 when I left Paris for Little Rock. 1957. This is 1980. How many years is that? Nearly a quarter of a century. What has happened to all those people, children, I knew then? What happened to this country? What does this mean for the world? What does this mean for me? Medgar, Malcolm, Martin, dead. These men are my friends, all younger than me but there is another roll call of unknown, invisible people, who did not die, but whose lives were smashed on the freedom road.

Alison: As Baldwin travels from Atlanta to sites of important history and brutal violence in Alabama, to his own family history in Louisiana, and then to Florida, he reflects on the efforts of the civil rights movement and evaluates with an honest melancholy about the reality for Black people in America 20 years or so after the tumultuous civil rights fight of the '50s and '60s. I Heard It Through the Grapevine is screening at Film Forum through January 25th. Joining me now is Director Pat Hartley. Pat, welcome to the studio.

Pat: Hi, thank you.

Alison: Scholar and Baldwin expert, Rich Blint. Hi, Rich. Welcome back.

Rich: Hi, Alison. Thanks so much.

Alison: Listeners, we want to hear from you. How have you engaged with the work of James Baldwin? Do you have a favorite book of his? You can give us a call. 212-433-WNYC, 212-433-9692. Maybe you want to share what his legacy means to you and your community or his activism in words. They make you move or make you think differently about America and its history. 212-433-9692, 212-433-WNYC. You may call in and join us on air or you can text to us at that number as well. Why are James Baldwin's words and beliefs important to you today?

Give us a call. 212-433-WNYC, 212-433-9692. Of course, our social media is available, @AllOfItWNYC. Pat, I just want to let people know that you're in studio with me and you are wearing a mask just for protection.

Pat: Yes, I am.

Alison: I just wanted them to understand what was going on if you sounded a little bit muffled.

Pat: Thank you.

Alison: What do you remember about your conversations with James Baldwin when it came to getting him to agree to collaborate on this documentary? You were friends.

Pat: Yes, well, basically we were-- I was working on a film about the Kennedy assassination and I've been going through all this black-and-white footage. We were in London at the time, so we got a lot of footage that you couldn't find here or if it was here, you couldn't get it. We were looking at it. I was pregnant at the time and we started talking about the children and the history. Where was our history? Did anybody write it down? Is anybody taking note? What actually, as he says, what's happened since then?

Of course, he was very clear that there was no end to a movement. Do you know what I mean? We like to do it, we like to tidy things up, he used to say. We were sitting there and he was very-- he was adamant that he would want to do a film, but it was not going to be about him. It was going to be about the people that he was talking to and that he was listening. That was the main impetus for the beginning of this.

Alison: Rich, as a scholar and expert on the life of James Baldwin, in the early '80s, where was Baldwin in his life professionally, where was he in the culture?

Rich: James Baldwin was on a significant decline. He knew that he was sick, but he was also being viewed as someone who was passé. That what anyone can tell us. I think this return to the South signal a renaissance for Mr. Baldwin and brought him back to the thing that gave him life. I think the opening that you just played for your audience, Alison, is really important about this other roll call of unknown, invisible people who did not die, but whose lives were smashed on freedom road.

My sense is that this opportunity with Pat and the recently late Dick Fontaine gave Baldwin a sense of renewed purpose and also allowed him that long look backward in a moment when both his work and his relevance to American national life was waning.

Alison: Pat, you made this with your husband, Dick Fontaine, who passed away last year. I wanted to acknowledge that.

Pat: Thank you.

Alison: Sorry for your loss. You are friends with James Baldwin, but you are also filmmakers.

Pat: Yes.

Alison: What were your goals as filmmakers, you and Dick?

Pat: The main thing was to have Baldwin be the camera. It was very important to Dick to not have the presenter in a historical documentary. Usually, we have a presenter, and they're going to tell you who they are and what you should be thinking about. The object here was to have no presenter and then it's up to you to figure out what it is that you're listening to and what it is that you're watching. Jimmy is the conduit.

Alison: I've got a text that said, "James Baldwin, prophet, truth teller, critic, voice of conscience, and poet."

Pat: Absolutely.

Alison: You got a clap, you got snaps from Rich Blint. Baldwin describes in the film how he first returned from Paris. We heard that clip and went to Little Rock and how he was in Selma and during the civil rights movement. Rich, what role did Baldwin take up when it came to the civil rights efforts?

Rich: He was this reluctant spokesperson. As he says in the film, his role was to bring the media with him. I think more broadly, his role in the civil rights movement was as a spokesperson for Black America, a role that he didn't relish, but that he fell into partly because of his enormous celebrity.

Alison: Sprinkled throughout the film is this long conversation with his brother, David. The two of them reflecting and talking in the way the brothers talk. It's just so interesting to see another version of the Baldwin genes, how they configured in someone else. Why was their conversation important to the narrative of this film, Pat?

Pat: Well, the film is very intimate in that we're listening to other people. When David and Jimmy talk to each other, they can say things to each other that they do not, I don't want to say publicly, but it's an intimate conversation. As you know from Baldwin's history, David was actually the forerunner. He would go south and come back and tell Jimmy about it. He was in the war, came back, and told Jimmy about it.

The way in which they talk to each other and the fun that they have, for instance, when they say, now the South has figured out what we know in the North, that you can't go here and you can't go there. You just got to figure it out. As to his bringing the press down, there were a great number of people that brought the press to the South. It was not a single effort. It was not a Black effort. I always feel like it was a principle effort. It was the principle of the thing and there were a lot of people involved with that.

There were people came from New York, people came from the South, from the West, and when Jimmy looks on the voter line.

Alison: My guests are Pat Hartley, filmmaker; and Rich Blint, the scholar. We are talking about the James Baldwin documentary. I Heard It Through the Grapevine, originally released in 1982. It's screening at Film Forum until January 25th. Let's take a call. Bob from Brooklyn calling in. Hi, Bob.

Bob: Hi, of course, I've always appreciated Baldwin's writing. I just wanted to mention an extraordinary opportunity which is available on YouTube for free, which is James Baldwin's debate with William F. Buckley at Cambridge University. You can look that up. James Baldwin versus William F. Buckley and experience the extraordinary persona of James Baldwin, and the idiocy and the ridiculousness of William F. Buckley. That's all. I want to recommend that to everybody who's listening, the famous Baldwin-Buckley debate, free on YouTube.

Alison: Bob, thanks for calling in. It was the basis of an off-Broadway show, I believe it was a year or two ago. Rich, would you fill in the blanks for people who weren't aware of what the Baldwin-Buckley debate was?

Rich: The Baldwin-Buckley debate in 1965, February of 1965 was whether or not the American dream was at the expense of the American Negro. As Bob characterized, it really showcases Baldwin's enormous abnormal intelligence and the rapid, indulgent persona, I would say in this case William F. Buckley. Baldwin receives, as you might remember, Alison, a standing ovation. Wins the debate, hands down. It's a really remarkable moment.

Alison: In the film, Pat, Baldwin hits the South, Atlanta, Birmingham, Selma, Mississippi, New Orleans, St. Augustine, Florida, a whole bunch of other places. We'll talk about some of them specifically. Generally, what questions was he looking to have answered? What was he going looking for?

Pat: He was looking to see where we are now. What has been the result of the civil rights movement? These were people that he'd interviewed in the early '60s, and he wanted to find out, what's going on now. We had no answers. We didn't go out with any, we had no script to find out. We know exactly what you're going to say. We had no idea what we'd find. In fact, the Gainesville University scene was the first place that we stopped, we put it at the end of the film.

Alison: Oh, interesting.

Pat: We were on the campus of the university. We were at a Pan-African literary conference. We had all of these literary people from all over Africa, including Chinua Achebe was there, and they cut in on the PA system, and they threatened to kill him. I think we were all shocked by that. I mean, I thought we'd find some, a little discomfort, maybe some disease. It's like anywhere you go, you can find that. The level of boldness was very surprising. Very surprising.

Alison: I want to play a clip from I Heard It Through the Grapevine. This is when Baldwin arrives in Atlanta, and he visits MLK's Memorial, and we hear his reaction and his voice. This is from I Heard It Through the Grapevine.

James Baldwin: I was wondering what Martin would've thought of his Atlanta now, an idea. All over the South now there, Martin Luther King Jr. drives freeways, expressways, and there is the monument in Atlanta, which is, this is a difficult thing to say, but I will say it, this is absolutely as irrelevant as a Lincoln Memorial. It is one of the ways the Western world has learned or thinks it's learned to outweigh history, to outweigh time, to make a life and a death irrelevant, to make that passion irrelevant, to make it unusable for you and for our children.

Alison: Rich, what is Baldwin ask about that observation?

Rich: It's cinematic, it's historical. It's also classic Baldwin in the sense, Alison, that he is going beneath the subterranean level. He understands that the effort to monumentalize, the memorialize is trying to mask the fact that he says in the film that some things have been changed on the surface, but nothing really has been touched. That's the Baldwin, I think, hallmark. There is the sense that he's going to get to the truth of the matter, no matter what. That Dr. King highways people who are now like Baldwin, safely dead.

No longer able to trouble, the peace that has been so dangerously, violently arrived at. I really love this idea that it's one of the ways the Western world has learned or thinks it's learned to outweigh history and to outweigh time. That Baldwinian intervention, which occurred over four decades, turns up in really candid and I think powerful fashion in the film that Dick and Pat produces.

Alison: Pat, why was he so willing to tell the truth?

Pat: For me, he had that ability to absorb your pain. It's your pain that he's absorbing. That's what he's talking about. He's not talking about himself in personal way. He says in Newark that the man is writing a story, he's not telling you the story. He's listening. It gives you a level of objectivity, was it difficult? Very difficult. It was exhausting for him. It was very unnerving to see and talk to some of these people. Again, he's not talking about himself. He has other writings which are directly related to himself, but in this case, he's listening to what other people have to say.

Alison: My guests are filmmaker, Pat Hartley; and scholar, Rich Blint. We're speaking about James Baldwin turning 100 this year as centennials being celebrated at Film Forum with a screening series. The first of which is Pat's documentary, I Heard It Through the Grapevine, originally released in 1982. It's screening through January 25th. If you would like to get in on this conversation, we would love to hear how you have engaged with the work of James Baldwin.

Perhaps you have a particular writing of his that is meaningful to you, or maybe you want to talk a little bit about his legacy, or how his words or activism have moved you. 212-433-9692, 212-433-WNYC. You may call in and join us on air. You can also text to us at that number, if that is more convenient, or reach out on social media, @AllOfItWNYC. After the break, we'll talk a little bit about the 1980s, and Rich Blint has put together a lovely Baldwin reader, a list of his works to check out. We'll get to All Of It after the break.

[MUSIC - Luscious Jackson: Citysong]

This is All Of It on WNYC. I'm Alison Stewart, my guest this hour, filmmaker, Pat Hartley in studio; and Rich Blint, a professor and Baldwin scholar. We're talking about James Baldwin's centennial. He would've been 100 this year. It's being celebrated at Film Forum with the screening series. The first of which is Hartley's documentary, I Heard It Through the Grapevine, originally released in 1982. It is screening through January 25th. We've got this very interesting text, Pat, and Rich, I'll get you both to respond to it.

This text says, "A friend of mine said Baldwin, 'Thinks too much.' I replied that Baldwin showed me how little most white Americans, especially the so-called educated ones, actually think." I can launch into a question from there. You might take a moment to think about it. It sort of dovetails into that comment is that this was recorded in 1980. Ronald Reagan launched his campaign in that year from Mississippi, and Baldwin visits the documentary, the place where he, Philadelphia. How did Baldwin view incoming Reagan administration?

Pat: Oh, with a wonderful humorous eye. He talks about Reagan saying, you can vote with your feet in the country. I have to tell you that none of us were prepared for the Reagan victory. Everybody thought that Jimmy Carter would go in for a second term. When I say that we didn't know what we were going to find, we also didn't know what we were going to find outside. I think what I learned from him is paying too much attention to what they think. He says that also in the film, it doesn't matter what you think anymore.

It matters what we think and what are we actually going to do. That's entirely up to the individual, just how we are going to do that. It's very interesting that he's not talking to us, and the people in the film are not talking to us either. They're having a conversation with him about their lives and there's been a lot of focus on them, and that takes up a lot of energy. I remember him telling me that all that focus on them. Do they understand? Do they not understand how nasty they are? How diluted they are?

It takes up a lot of energy and then you don't have much energy left to take care of your own house.

Alison: Rich, in your study of Baldwin, how did he approach politics? Was it something he wanted to engage with directly? Was it through his writing?

Rich: Well, he wanted-- famously, with Bobby Kennedy, that meeting he had back in 1963, that we're moral confrontation with the history they were producing. I want to go back if I can, Alison, because of that caller before.

Alison: Sure. Of course.

Rich: The idea that Baldwin had famously said that Americans can't bear very much reality. He also has a famous essay called, As Much Truth as One Can Bear and then a little more. This idea that Baldwin thinks too much is absolutely hilarious and fictional. What it is, is that people like their comfortable innocence, their truths, as they understand them, and hated the fact that he was so penetrating in unmasking those fictions. I think, in terms of the political realm to return to your question, Baldwin was insistent that this country achieved itself, achieve this thing called American democracy, that it's been squandering for so long. Politically, Baldwin was committed to that.

Alison: Pat, in the film, there are so many children. There's even a part of the film when it's just the children's faces and you hear the adults speaking off camera, but it's just these beautiful young faces. Why was that important that children be part of this conversation and this story?

Pat: Well, it's the legacy. It's just so interesting. You got two people just singing folk songs about what happened. I remember hearing when I was a kid reading about the labor riots in the automotive plants at the turn of the century, and people had grandparents that they didn't know anything about it. I grew up that way. There were relatives from down from the South. Some people talked about it, other people did not. It's the same from people with the Holocaust. Some people would talk about it, other people acted like it didn't happen.

He's asking us just to think about it ourselves. He didn't tell me what to think. He liked being the voice. He also told me that he never wrote anything while he was in New York. It was just too painful to physically write in the United States, so he would go to Europe. He would do the writing there. It was kind of he would research it. I understand what he's talking about, that it's very painful in your heart. A lot of his writing has to do with other African-Americans. Jimmy says to Hoyt Fuller says, "What do these Black college students think that they're doing? They can't all have Toyotas."

Alison: I'm laughing now, but I have a serious question. Pat, did it take a toll on him making this film? You were talking about what a sensitive person he was.

Pat: Absolutely, yes. We had to have some rest periods. He was in a car for hours traveling. We were not welcome in most of the places that we arrived in, so we kept on going. We also had an English crew. One of the young ladies on the crew, there was a white supremacist on trial in Birmingham. That is actually a distant relative of hers from Plymouth, England.

Alison: Oh, my.

Pat: Everybody was having an interesting time.

Alison: Yes, I'd say so. Rich, I wanted to note in the film that Baldwin spends a lot of time in the South, but the film spends a good amount of time in Newark, in our backyard here, and the devastation of the '67 uprising. He's clearly shaken by what he sees in the film. What do you make of the inclusion of his experience in Newark in the film? How does it help tell this story?

Rich: I think it's a powerful decision that was made cinematically. I think, his comment along with David Baldwin's comment that what happened in Newark, the housing of those people in those projects, which are really reservations or concentration camps, he says, without the barbed wire, signals to the country that they abandoned the community of Black people who revolted, what Baldwin calls the latest slave rebellion. I think it was really important to leave in and see what happened to those neighborhoods, which they left alone.

Amiri Baraka were companies, but both Baldwin brothers in Newark says they've been urban renewed. The fiction of American progress, what we see in the film is that there have been, again, dispossessed. I think it's really crucial that we don't romanticize the [unintelligible 00:24:39], that we understand that the-- the spirit of America is the spirit of the South or vice versa, that it's one country as Baldwin always maintained.

Alison: Just got a great text. "1980, perhaps corner of 57th and Sixth Avenue, waiting for a light, James Baldwin, Farrah Fawcett, and Wallace Shawn. People bounced around until all settled around surrounding Baldwin. I thought to myself, 'We're going to be all right.'" Loved that text from one of our listeners. Thank you who shared that story. We are discussing the centennial of James Baldwin. We're discussing the film I Heard It Through the Grapevine. It is screening at Film Forum now through January 25th.

Rich, we asked you in honor of Baldwin's 100 centennial to put together a reading list for our listeners. Would you mind reading from your list the short synopsis of each? Do you think we can do that?

Rich: I think we can. Of course, we have to go with The Devil Finds Work, Baldwin's account of the fiction of American cinema. No Name in the Street is also there, what happens to him after all those famous American assassinations in the 1960s and just how, not bitter, but how demoralized and sad he was about where his country had landed.

There is also an amazing text, Giovanni's Room, that was paired with another country about the figure of the white, heterosexual man who is denying his feelings for men, Baldwin's account in 1956 and his famous The Fire Next Time in 1963, which of course, ushered him into remarkable celebrity, his account of the failure of the great project of American democracy. I think any one of those books, Alison, would be a wonderful introduction to the life and work of James Baldwin.

Alison: Pat, did you want to add anything to that list?

Pat: Yes. There's a book that we read. It was Rap on Race. It's a conversation with Baldwin and Margaret Mead. It's beautiful. It's misinterpretation of one and the other. They're having a conversation and it's like neither of them are actually talking or are actually listening to each other. Jerome had told us this story. I was in high school in 1963. They had torn up pieces of the Baldwin book and they kept them. Each one of the people in jail had little pieces of paper writings from that book and The Fire Next Time.

It just reminded me that Baldwin is also an American scholar. All that leafleting and essay writing, and soapbox standing, all of that-- he was a scholar of American history and also English history. He's very Dickensian in Go Tell It on the Mountain. It's wonderful how he knits all of those things together. He and Achebe were trying to have a conversation about why Achebe didn't write in his native African language. Why did he write in French? Well, that conversation quickly petered out, but it's interesting.

Baldwin writes in English and he doesn't write in a colloquial English, which was a big issue when I was a kid, when Langston Hughes wrote various poems in colloquial Black English. Jimmy did not do that. He wrote in English.

Alison: My last question for you Rich is after someone sees this film I Heard It Through the Grapevine, what do you hope they understand about James Baldwin that maybe they might not have understood going in?

Rich: What I hope they understand is how rare he was, how rare he was as someone who was willing to witness, willing to bear witness to what the country is and is not and how much he's willing to take that long look back about how we failed that generation of people who fought to give us the rights we have now, and how that has been squandered in the intervening 40 years.

Alison: I Heard It Through the Grapevine is now at Film Forum through January 25th. I've been speaking with its director, its maker Pat Hartley; as well as scholar and Baldwin expert, Rich Blint. Thanks to both of you for the time today.

Rich: Thank you, Alison.

Pat: Thank you, Alison. Oh, can I just say one more thing?

Alison: Real quick.

Pat: Go see the film because it will energize you. The people in it will give you so much energy and so much hope that you could just go out and do something. That was really the point. Thank you.

Copyright © 2024 New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.

New York Public Radio transcripts are created on a rush deadline, often by contractors. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of New York Public Radio’s programming is the audio record.