The History of the Star-Spangled Banner

( Smithsonian Institution Archives / Flickr )

[music]

Alison Stewart: This is All Of It from WNYC, I'm Alison Stewart. We are headed into the 4th of July weekend, where at some point you will likely hear a version of this.

[music - Whitney Houston - Star-Spangled Banner]

Whitney Houston: And the Rockets' red glare, the Bombs bursting in air,

Gave proof through the night that our Flag was still there,

O! say does that star-spangled Banner yet wave,

O'er the Land of the free and the home of the brave?

Alison Stewart: That is the Star-Spangled Banner, as performed by Whitney Houston in 1991 at Super Bowl XXV, a rendition that has become a high watermark for performances since. The anthem has undergone many transformations since Francis Scott Key wrote the lyrics in 1814 and been performed for many different occasions, at times of war, at times of peace, at sporting events, at concerts.

The anthem has been used to honor American institutions and as an opportunity to highlight hypocrisy, such as when Olympic runners Tommie Smith and John Carlos raised their fists while it was playing during a medal ceremony in 1968, or with NFL player Colin Kaepernick in 2016. The lyric about the land of the free hits differently for Black Americans, and the fact that the man who wrote them came from a family that enslaved people.

In the book, O Say Can You Hear?: A Cultural Biography of The Star-Spangled Banner, University of Michigan Musicology Professor Mark Clague explores the history of the anthem and its many uses and iterations. Since we're heading into this holiday weekend, we figured now was the perfect time to revisit this conversation with Mark. I began by asking him who Francis Scott Key was before he wrote the lyrics to our national anthem.

Mark Clague: He was born in 1779, and so I think of him as a founding son of the nation. Of course, the Declaration of Independence, 1776, we just celebrated our first day anniversary of that on the 4th of July. Key is one of those people that puts the Constitution into action, in a sense. He's a lawyer. He's not a plantation owner per se. He moves to Georgetown to be part of the federal government. At the time when literally the Potomac is like a swamp.

They built Washington D.C. in the middle of nowhere, literally, because that way nobody had any claims to it. I think Francis Scott Key was one of the people who was putting the Constitution into practice. As a lawyer, he argued cases before the Supreme Court. He was a pretty prominent figure, but he was known more a pious man, as an eloquent man and as a lawyer in his day.

Alison Stewart: The song recounts Key's experience in Baltimore during the siege of the city by the British in the War of 1812. You write in the book about the specific flag the song refers to. What else do we know about the Star-Spangled Banner that inspired the song?

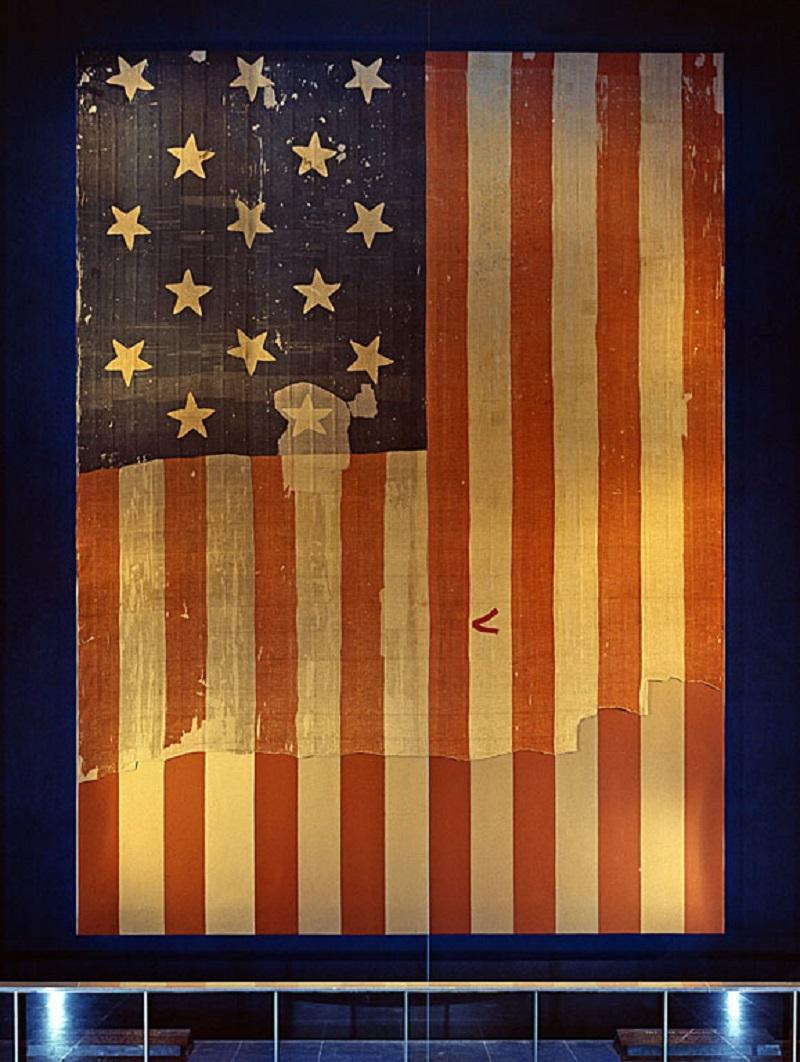

Mark Clague: The actual flag now is in Washington D.C. at the Smithsonian Museum of American History. It's a pretty amazing exhibit, almost a cinematic experience to go visit it. You walk down this tunnel and it gets darker and darker, darker, and there's barely any light to protect the fabric. One of the interesting things about it is it's a different design than our flag today. Not only were there a different number of states, but there were 15 stars and then 15 stripes on that flag.

The idea was every time you added a state, you'd add both a star and a stripe. One of the other interesting things is that there were 18 states in the United States during the war of 1812. The number of stars and the number of states didn't match at the time, and nobody cared. As a symbol, the flag was something the military used. It was something the Navy used, but it was not something in every school and every home like we have today. Really, the flag and the song have been in a symbiotic relationship.

Francis Scott Key's song helped make the flag as a symbol more important. In fact, the notion, the phrase 'Star-Spangled Banner' was invented by Key for that lyric, and that's the name that we now call the Flag. Before that, it was known as Old Glory or the National Flag, but it was not known as the Star-Spangled Banner until Key wrote that famous chorus.

Alison Stewart: My guest is Mark Clague. The name of the book is O Say Can You Hear?: A Cultural Biography of The Star-Spangled Banner. He wrote the lyrics. The tune existed before, what was it?

Mark Clague: Yes. This is one of those myths I talked about that I knew, as a kid, that was more fantasy than fact. It's often said that Francis Scott Key wrote a poem, and that someone else noticed that it happened to fit this particular tune. The melody is from 1773. It's from London, England, and it was written for a musician's club. One of the other things that tells us-- everybody says like, "The Star-Spangled Banner is too hard to sing. It's [unintelligible 00:05:47] of these high notes." It was supposed to be hard to sing because it's the theme song of a club of musicians who wanted to show off that their members were better than the members of other clubs.

They wanted a song that really featured their skill and virtuosity. It was intended to be a show-off song, not to be in a song that was sung by 100,000 people at a sports stadium. That's part of it, but this was a really common practice in early American history, was to write new lyrics to a well-known tune, like a folk tune, and that would reflect current events. It could be a campaign song for a political party, it could be a 4th of July song. A lot of them were. It could be a song marking a pivotal moment, like an important happening.

That's what Francis Scott Key did. He took a melody that he already knew, and he imagined some new words to describe an event that he had witnessed. It's often said that these what are known as broadside ballads or newspaper ballads. They're like the early tweets and TikToks of federal America, if you will, because they went viral. They printed it in one newspaper, and then the next town this newspaper would pick it up and reprint it, and so on and so on.

That's what happened to Key's lyric that made it so famous. It's not about the information. It's not about telling people that, "Hey, wow, there was this miracle and the United States won the Battle of Baltimore." It was more about conveying the emotional impact of the news. Today, we have live audio and video, and the news can almost put you in the scene. In 1814, none of that existed. None of that technology existed. Music was used to bring the emotion of the news to the fore.

Alison Stewart: The name of the book is, O Say Can You Hear?: A Cultural Biography of The Star-Spangled Banner. Let's hear a modern recording of the way it would've been performed in 1814. This was uploaded to YouTube by the Star-Spangled Music Foundation, and you actually edited the music and are featured in the chorus. What should we listen for, particularly Mark?

Mark Clague: Yes, it's different than we sing it today. It's an upbeat party song, if you will. This is 1814. We just beat the British and Francis Scott Key is excited about it. It's quicker, rolling triple meter like a fast waltz almost. It's pretty high. It's sung by a soloist, not by the crowd. Then the other important thing is that there's this social ritual built in to the music. It's actually longer in 1814 than today.

The reason it's longer is because that last chorus, that last pair of lines, "O! say does that star-spangled Banner yet wave, O'er the Land of the free and the home of the brave," is sung twice, first by the soloist and then by the crowd, by everybody assembled echoes it back.

Alison Stewart: Let's take a listen.

[music - Star-Spangled Banner]

O! say can you see by the dawn's early light,

What so proudly we hailed at the twilight's last gleaming,

Whose broad stripes and bright stars through the perilous fight,

O'er the ramparts we watch'd, were so gallantly streaming?

And the Rockets' red glare, the Bombs bursting in air,

Gave proof through the night that our Flag was still there;

O! say does that star-spangled Banner yet wave,

O'er the Land of the free and the home of the brave?

O! say does that star-spangled Banner yet wave,

O'er the Land of the free and the home of the brave?

Alison Stewart: There we go. We play just the first verse. The Star-Spangled Banner has four verses. Mark, when did that verse start to be the preferred and performed exclusively?

Mark Clague: It's really when the anthem starts being used for community singing. Rather than have a soloist sing all the words and the audience echo back the last two lines of each verse, we get into having groups of people sing it. Right around World War I, the turn of the century, 1900, and this was part of what was called the Community Singing Movement. When you had the crowd singing it, it didn't make any sense to have the crowd echo back what the crowd was already singing, and so you cut out that choral repeat. You also started using it more for civic ritual, so it was performed as part of political rallies, rallies around World War 1 in particular, later about sporting events in World War 2.

At that point, we dropped the other verses because it basically just took too much time. It takes a little over a minute to sing each verse. Now, we handle the anthem in about a minute or if you're Aretha Franklin, it takes about four and a half minutes. The other four verses, it's just cut, I think, for ritual reasons of time.

Alison Stewart: Mark, just to be clear, when did the Star-Spangled Banner become the national anthem?

Mark Clague: The usual answer to that is 1931 because that's when president Herbert Hoover signs a bill that's passed by Congress that reads in full, like this is the whole thing. It just says, "The words and music known as the Star-Spangled Banner is the national anthem of the United States."

What I argue in the book is that it's actually the US Civil War that transforms Key's song from a typical patriotic song, a national song is what it would have been called at the time, into the singular national anthem.

It's because of the way the Star-Spangled Banner, the flag and the stars that represented the state, becomes the symbol of union. When the confederate states secede, they don't take any stars-- The federal government, it doesn't take any stars off the flag. There's no allowance for the fact that the states have left, and so the Civil War started to retain the Union, but also very intentionally to end slavery, and this is pretty clear from these alternate lyrics.

I found like 580, 600 of these lyrics, but there are a couple really fascinating ones. One is right after Abraham Lincoln is elected and it says, "Finally, we're going to end slavery." It's sung to the tune of the Star-Spangled Banner because this is the critical question facing the country. The other one actually comes from Boston. It was written by a famous poet at the time, Oliver Wendell Holmes Sr., and it's a fifth verse to be added to the Star-Spangled Banner. It actually has a line, "By the millions unchain'd who our birthright have gained," so, whose citizenship, whose freedom have gained. "May we keep our bright blazon forever unstained." This lyric, which is from April of 1861, so right at the very beginning of the Civil War, saying, "We've got to end slavery."

There's a way in which I think the anthem becomes the musical rally and cry of the Union army during the Civil War. It's actually used in battle to inspire troops to fight more valiantly, and it plays an important role in galvanizing the Union army and leading to the eventual victory in the Civil War.

Alison Stewart: You brought up enslavement and we have to talk about the fact that Francis Scott Key was a slave owner, as D.C. district attorney and for slavery is part of the law. He helped slave owners reclaim their property. His family earned their money largely with the enslavement of human beings. What do we know about his personal views on slavery, and how did it affect your research and your writing of this book?

Mark Clague: For me, Colin Kaepernick taking a knee was a real challenge to me as a historian to dig deeper into this question about the relationship of Black Americans to the nation, but through the Star-Spangled Banner specifically, and really to try to probe what Francis Scott Key thought. Was he a person that I could write about or dig into? It really was a personal crisis for me to deal with.

I looked pretty deeply into who is a pretty flawed, complicated, and contradictory character. His own personal views on slavery, I'm not sure I could even say. One of the weird things about him is he becomes a kind of contradictory figure who's on both sides of the slavery question. He owns people himself as captive labor. His wife was from one of the largest slave-owning families in Maryland.

Actually, his wife's brother owned Frederick Douglass briefly when he was a kid, when Frederick Douglas was a kid. Yet, Key also volunteered his services as a lawyer fighting for the freedom of Black men, women, and children in court, in what one of my colleagues has called a kind of legal parallel to the Underground Railroad. He was responsible for the freedom of at least 189 people through 106 different court cases, many which he lost, but some of which he won.

This was a time in American history when slavery was legal. As a lawyer, Key was responsible for defending the law. He was even appointed district attorney of Washington D.C by the pro-slavery president Andrew Jackson. He was responsible for putting down abolitionist movements, for example, of the pamphlet campaign. There was a race riot, a white race riot against the Black community in Washington D.C in 1835 that Key, at the very least, made worse and may have actually caused himself.

Interestingly, he prosecuted the white rioters as well as some of the Black Americans who were involved with the riot. He doesn't fit exactly the good guy, bad guy notion that we have now of being an abolitionist or a pro-slavery advocate. He's both in a weird kind of way. Strangely, I don't actually think he was that unusual for the time. I think this was an issue that the whole country was struggling with.

Key's real moral failing was to rubber stamp the compromise that have been used to sign the Constitution. The United States was founded on this kind of devil's bargain to permit slavery to unify the colony to the early states, some of which allowed slavery and some of which did not. Key went along with that. He's on the wrong side of history, for sure, but he's not just someone who was an advocate or accepted slavery. He actually in his own mind was working towards a peaceful end of slavery in the United States, and that was impossible, right? It took a Civil War to end slavery in the United States, so he was imagining an impossibility.

I think he's actually a figure who's worth knowing about, and knowing about him helps us understand the United States. This crazy compromise that was used to found our country.

Alison Stewart: I wanted to ask you about protest, because you trace the history of anthem activism in your book, especially by Black athletes to 1959 U.S high jump champion Eroseanna Rose Robinson [crosstalk]

Mark Clague: It's Eroseanna.

Alison Stewart: Eroseanna, thank you. Tell us about who she is, and where and what she was protesting.

Mark Clague: The was during the Pan Am Games, and I think it's the same thing that the man who got a lot more attention later on, like Tommie Smith and John Carlos, just a discomfort with the United States, with the direction of things. This is '59. It's before the Civil Rights Act of '64. Martin Luther King is still being treated as a fringe radical figure. Not the hero that we think of him as today.

It's a time of real crisis in the United States, and Rose Robinson refuses to stand for the national anthem at a major international event. It's the first time we have a prominent African-American athlete, but as a woman, women who protest tend not to get the attention that the men do from the media. That little tidbit is lost to history. The other amazing thing I found was the very first documented protest that I was able to find was from 1860 of a Black woman refusing to stand for performance of the anthem. The history of protesting the anthem goes back to alternate lyrics calling for abolition, calling for women's suffrage, calling for changes to union rules, and labor law, and all sorts of things that go back to 19th century.

As the melody gets more and more associated what it means to be American, people use the anthem in different ways to express different political opinions. In the 19th century, that was about writing different words. In the 20th century, it was about Whitney, it was about José Feliciano, it was about Marvin Gaye saying, "Making an identity claim that I'm here and people like me are here because you could hear it in my music."

Alison Stewart: Let's actually listen to that version by José Feliciano. Let's play D four.

[music - José Feliciano - The Star-Spangled Banner]

Alison Stewart: My guest is Mark Clague, and his book is O Say Can You Hear. A Cultural Biography of The Star-Spangled Banner. I want to point out something that's from the introduction of your book. You write, "The national anthem, the Star-Spangled Banner, phrases a question. It says, "Does that star-spangled Banner yet wave,

O'er the Land of the free and the home of the brave?," that it's actually a question. Why is that important to point out?

Mark Clague: Yes. I think my book is trying to offer a different vision of the anthem as something that's mutable, that's responsive, that's something that's expressive of protest as much as patriotism, that's plural rather than singular. I think we misunderstand the anthem, and maybe patriotism itself, as something that's unchanging and absolute, that's a sacred icon, rather than a vehicle for expression of hope. Love and hope, to me, are pretty closely related. What I hear in Hendrix, what I hear, actually, in the original Key version is a kind of hope, an ability to have a vision for what the country might be like going forward.

For me, it's a problem if one political party owns the anthem. This has to be the anthem for all of us, and we all have to be moving forward. I think among my students, I see that they're really confused about the anthem. It doesn't make a whole lot of sense to them. What I'm trying to argue is that there's this tradition, say, of translating the anthem into many many different languages as a gesture of welcome to different people to come and be part of this big democratic experiment.

I think we've lost touch with this, that the anthem is being used more like a weapon. That's not the vision of patriotism I think we need to embrace in order to have the history of our country as Martin Luther King said, "Bend the arc of history towards justice." I really think that patriotism and many people I know just feel alienated from the song. What I want to say is this song actually is something that's about the fantastic possibilities of America that there's so much pluralism, diversity, different ideas, competing debate. There's a conversation about the country that's happening through the anthem, and stylistically, musically, lyrically. If we tap into that, I think it's a real source of energy for moving this country in a more positive direction.

Alison Stewart: The name of the book is O Say Can You Hear?: A Cultural Biography of The Star-Spangled Banner. It's by my guest, Mark Clague. Mark, thank you for being with us.

Mark Clague: Thank you, Alison.

Copyright © 2023 New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.

New York Public Radio transcripts are created on a rush deadline, often by contractors. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of New York Public Radio’s programming is the audio record.