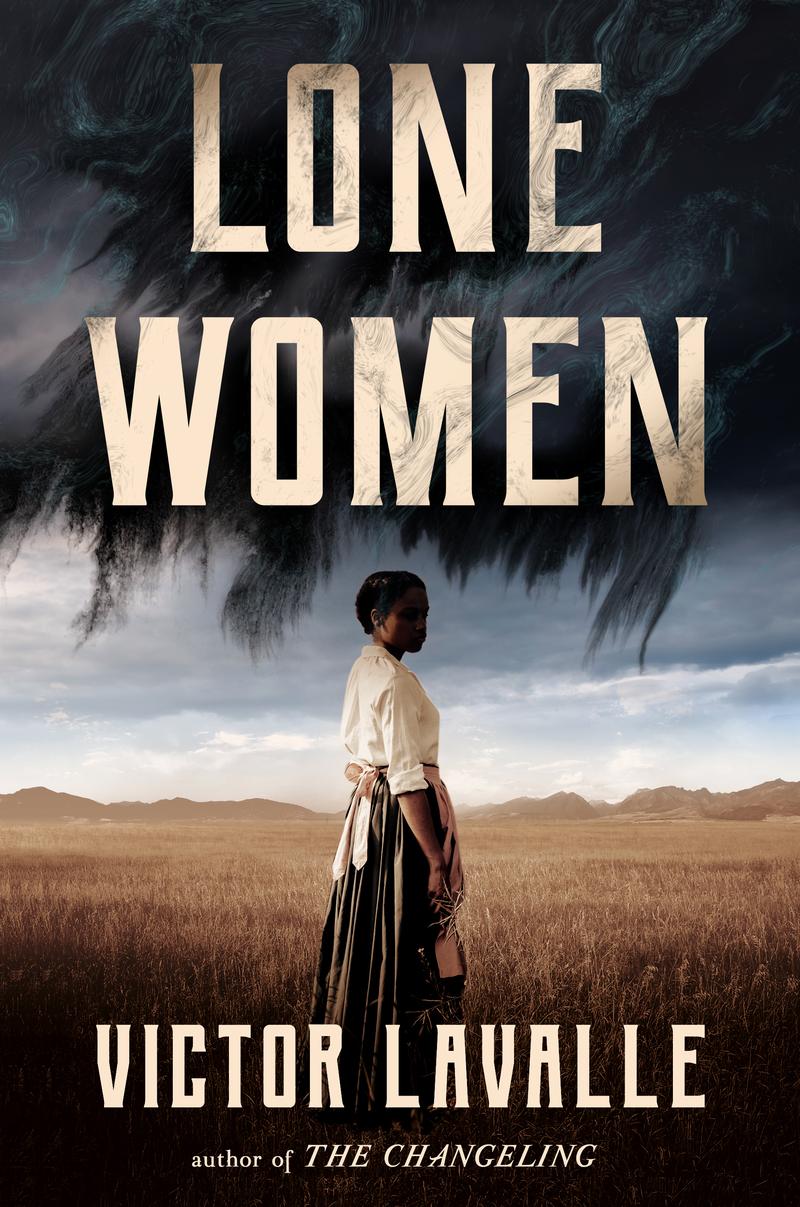

Get Lit with All Of It: Victor LaValle

( Courtesy of Penguin Random House )

[music]

Alison Stewart: You're listening to All Of It on WNYC. I'm Alison Stewart. The New York Times review called the latest novel from New York-based author Victor LaValle enthralling. We agree, which is why we selected it for our May Get Lit with All Of It book club. The novel is titled Lone Women. The story takes place in 1915. A young Black woman named Adelaide is fleeing her family farm in California. Something terrible has happened there and she needs to leave it behind.

She brings very little with her, except for an exceptionally-heavy steamer trunk, which she keeps locked at all times. Adelaide gets a plot of land in Montana as part of a new program designed to promote agriculture in the area. All she has to do is turn the land into a viable farm and it's hers. Adelaide is very isolated on the homestead as a Black woman alone in the majority-white town of Big Sandy, Montana. If the powers within her steamer trunk become unleashed, Adelaide's new start and her very life could be threatened.

In a starred review, Kirkus says the novel is "a winning blend of brains and occasionally violent thrills." Victor LaValle joined us for an in-person Get Lit with All Of It book club event at the New York Public Library earlier this week at the SNFL rooftop event center. It was great to see everyone in person. I began my conversation with Victor by asking how he got the idea to write a book set in Montana.

Victor LaValle: Actually, I was in Montana because I was doing an event at the University of Montana. What I tend to do when I'm in a place where I think I probably won't be back again, I try to buy a book of local history so that, later, I can read about the place where I was because it's pretty rare that these visits last long enough to actually get to know the town or the city or whatever it might be.

I was in their bookstore in their local history section. This one book in particular came across my view. It's called Montana Women Homesteaders: A Field Of One's Own. It was just about single women homesteaders. The first question I had was I didn't know those existed, what is that, because I'd assumed that homesteaders were just what I had seen in TV and movies. It was a white dude, the end-

[laughter]

Victor LaValle: -or sometimes it was a white family and there was maybe more of a Laura Ingalls Wilder kind of Little House on the Prairie thing. Even there, we all know Dad was the main character, right? That's what I thought homesteading was. As I read this book, I discovered that, in fact, the rules of the time allowed for single women or widows to claim land on their own and that, in fact, the federal government was so desperate to have this land, for lack of better terms, colonized that they even made it so that it wasn't only white women who could claim this land. Black women could claim the land. Latinas could claim the land. Chinese women could not even though they were a large population there. Chinese were the people who were the most openly, legally segregated or-

Alison Stewart: Excluded.

Victor LaValle: -excluded at that time. I just couldn't believe. Then there was, of course, the native populations. They at the time could not claim the land because they were being pushed onto reservations. All of this was so much more complicated than my picture of the time. My next thought was, "Well, I'm just some ignorant kid from Queens. I don't know anything about Montana's history. Maybe everyone here knows all of this already." I asked these folks who I had met at the University of Montana, people who had been raised in the state, and I said, "What do you know about the Lone Women?" To a person, they all said, "What's a lone woman?" That's when I said, "Oh, maybe it's not just me. Maybe I can tell a story."

Alison Stewart: We asked our book club members. We have a whole book club on Instagram in between these live events, how many people had been to Montana, and what they remembered about it? One person said, "Warm hospitality of the Blackfeet Nation and the beauty of Glacier National Park." What was it about the physicality of Montana that inspired you?

Victor LaValle: Many years ago, I had a visiting writer job at Mills College in Oakland, California. I was there for two years. While I was there, I bought my first car that I ever owned, an Acura Legend. I was so proud of myself. It had no air conditioning. At the end of my second year, I had to drive back to New York. It was May going into June. I could either drive south across the country with no air conditioning or I could drive north across the country. I had a cat, an old cat.

Alison Stewart: [chuckles] The story gets better and better.

Victor LaValle: We went north across the country. I went along Route 2. Because of that, I went through Montana. I hit Glacier National Park. I saw Crater Lake and fell in love with it. Also, as I was driving across that route, all along the path, you'd see abandoned farmhouse, a fallen-over silo, this or that. It started getting into my head like, "Where did those people go?" Those places look like half haunted houses, half historical relics. At that time, I was not at all thinking about writing this book. I just fell in love with that landscape. Years later when I read the history book, I said, "Oh, that place. Oh yes, I want to write about that place because I still remember it and I still love it."

Alison Stewart: What is a small detail from your research that made a big difference?

Victor LaValle: Well, one of the ones that was a lot of fun was finding out-- one of the ways I did research was that I found this-- The local paper was called The Bear Mountain Gazette. Online, they have every weekly issue starting in 1909 going up to maybe 1920-something. For a year or two, I just read every week's issue from 1911 on.

Alison Stewart: Wow.

Victor LaValle: Because in that way, rather than getting what a history book gets into, which is the big movements of this or that, and World War I is starting across the sea and all that, here I get to see what people cared about little by little. One of the things that popped out at me was how much they despised the new catalog system that was getting people to buy their goods through the mail rather than from local store owners. They were really like, "Don't buy from the catalogs. You got to buy from home." I was really like, "Oh, I think I understand this issue."

[laughter]

Alison Stewart: I literally put my book a little LOL on this part that says, "Support local businesses, not some scoundrel with a warehouse out in the state of Washington."

Victor LaValle: Yes.

[laughter]

Victor LaValle: They didn't pinpoint Washington. I thought for the modern reader, I would make it more specific.

Alison Stewart: [laughs] Well, before I start with the beginning of the book, Big Sandy is a real place though.

Victor LaValle: It is. I apologized to the people of Big Sandy. In the back of the book, and I swore, I said to everybody, "Please don't. Nobody in Big Sandy tried to kill all the lone women or anything like that. In a weird way, I learned this lesson. A previous book of mine called Big Machine took place in Oakland, California. I wanted to write about my time there. One of the things I did was I changed Oakland to the city of Garland, California just because, in that book, I have homeless people blowing up the East Bay Bridge. I have all these terrible things happening. I thought people might take this the wrong way. Then when I did events in Oakland, people were like, "You should have blown up Oakland."

[laughter]

Victor LaValle: "Why didn't you say it was Oakland?" They really wanted to claim all that, right? This time around, I said, "I'm not going to pretend it's a different place. It's just going to be a place that just fits what I needed. Then in the back, I'll make clear. Big Sandy itself should not be blamed for my book."

Alison Stewart: Have you heard from anybody from Big Sandy?

Victor LaValle: So far, nothing.

Alison Stewart: Okay.

Victor LaValle: Maybe it hasn't made it across their radar yet.

Alison Stewart: You start the book with a bang. Adelaide burning down her house. The body of her parents inside were not clear yet, what happened to them, and what Adelaide's role is in their deaths. Why did you want to start this way?

Victor LaValle: Well, certainly, I feel like they often say, "Start a story at the moment when it becomes the most urgent." I figured this was a really urgent moment. Also, I thought there was some fun in playing with the reader's perspective like, "Should I hope that Adelaide gets away with this or should I think that she's an awful person and a murderer of her parents?" I wanted that ambiguity to start right at the beginning because, on some level, that's how Adelaide feels about herself. She's not sure if she's the hero or the villain of her family story.

Alison Stewart: This is the opening line of the novel Lone Women. "There are two kinds of people in this world. Those who live with shame and those who die from it." Was this always the first line?

Victor LaValle: No. Usually, I think almost without fail, the beginning of my book is always the last thing that I write. I have a beginning in the early drafts, but it stinks.

Alison Stewart: [laughs]

Victor LaValle: I have to learn the whole book before I can understand what's the place to begin. Because before that, I'm just casting around. I wrote the whole book before I understood that, deep down, the point of the book was family shame, family secrets, and how people deal with them. Then really, almost at the very end, I came up with that opening line and felt like, "Okay, this will set things up."

Alison Stewart: One thing Adelaide's mother told her and it keeps repeating over and over again is a woman is a mule. First of all, is that a reference to Zora Neale Hurston?

Victor LaValle: Absolutely, yes.

Alison Stewart: Their eyes are watching, "God." Just wanted to make sure. What does her mom mean by this?

Victor LaValle: It was a reference to Zora Neale Hurston for sure, but it was also a version of something my grandmother felt and said without reservation, which was that she would-- I was raised by my grandmother and then my mother and then there was my sister and I. My grandmother was just a super grim person. She just was. I still remember one of my favorite stories about my grandmother that tells you about who she was is maybe when I was six or seven. I'm sitting with her and I say, "Grandma, I hope you live to be 100." She says, "Don't curse me."

[laughter]

Victor LaValle: "I don't want to live that long, please." It really threw me off, but at the same time, I was just like, "All right, that's my grandma." She's got an idea of, "This is enough." That way of talking was really normal to her. Her own life had shown her again and again that as the woman who was the matriarch of the family, she would clean up a lot of other people's messes. She would carry a lot of other people's weight and there was no respite from that.

She took a fatalistic view about the reality of the burden of being the woman in a family. I would hear her often telling that to my mother, right? My mother hated it. My mother did not believe that. My mother wanted nothing to do with that, and yet at the same time, she moved my grandmother in with us and became her caretaker. As far as she was concerned, my mom said the greatest relationship of her life was her and her mother. She was so happy that that's the person who she lived most of her life with. My grandmother was a downer. She just was.

[laughter]

Victor LaValle: She was also unbelievably resilient and she did do the work. You could rely on her. It's just that she wasn't going to be like, "I'm so happy to carry everyone's weight." She'd be like, "This sucks, but all right."

Alison Stewart: We learned that Adelaide loves to read and there's one book she particularly loves, The Tenant of Wildfell Hall by Anne Brontë, one of the Brontë sisters. Some people have called this a feminist novel. Why does Adelaide love this book so much?

Victor LaValle: You see books sometimes where the character in the book is reading another book. It's often a book that, in some way, speaks to the larger ideas of the book you're reading. That novel by the least-known Brontë is very much-- one of the central ideas is it's about a woman who leaves an abusive husband and makes her own life.

I felt that would be the kind of thing that it would ring a bell in her because, in her own life, her mother's telling her a woman is a mule. She's living on a family farm where they're walled in by their family secret. Essentially, she knows she's just being trained to take over this responsibility. If her family at night would read a book about a woman who flees the burden of the people around her, she would be like, "Yes, I like that. I like that a lot."

Alison Stewart: In the book, you get the sense of how difficult daily life was, just how harsh the conditions were. People were starving. People were freezing trying to make it through the winter. When you did your research, what were some of the challenges specifically for female homesteaders?

Victor LaValle: Well, I think in some way, at least in the stuff that I was reading, particularly in that book, it went less into the-- Well, maybe the biggest challenge was perhaps being able to find people you could trust, right? Everyone was facing the hardships of that landscape, but then the secondary question was, "Sure, your neighbor might show up to help you when the roof caves in or whatever, but could you trust your neighbor to leave afterward?"

What you did find in the history was that the lone women often banded together and that they were each other's best comfort. That rang true to me just because-- One of the inspirations for the book certainly was my own wife, who has a number of friends who all serve different purposes. She serves a different purpose in their lives. They are each other's greatest support system in a way that they certainly don't ever go, if they have male partners, to their male partners. On the other side of things, as a man, I have one best friend and he lives out in Portland. We talk on the phone sometimes, but that's it.

[laughter]

Victor LaValle: I really was so amazed and impressed by the idea of that kind of social network and the ways that they could support each other. It just seemed, to my mind, such a gift to have that.

Alison Stewart: Ooh, it makes the last three pages of the book. I feel all tingly thinking about it. We asked our readers what homesteading skills they thought they had. Someone said, "I knit and I'm militant about food waste." Another said, "I'm a MacGyver kind of guy." Our producer Kate said, "I could probably run away from bears very quickly."

[laughter]

Alison Stewart: What skill do you think you have? How would you have survived?

Victor LaValle: That's hard. I got to say even now, sometimes my wife will say, "Let's go camping," and I immediately am looking for the glamping version of that. I am the one who's like, "There's got to be a hotel somewhere in Montana." I would die is essentially the truth.

Alison Stewart: I love the name of the Mudges, the Mudges who enter this story. First, we think, "Oh, it's these four blind boys and their mother, and they're trying to make their way across." We learned that they're just grifters and hugely problematic. First of all, how'd you come up with the name Mudge?

Victor LaValle: That was my revenge on some neighbors who my mother really hated.

[laughter]

Victor LaValle: It's not their exact name, but it's super close. They were terrible to my mom. That's my perspective as a loving son. Maybe she was terrible to them. I don't know, but their kids didn't write a book.

[laughter]

Victor LaValle: I just wanted to spit on their name in a book and so I gave it to some of the worst people in the book. I also just thought the name, "the Mudges," it just sounded so like, "Don't mess with the Mudges."

Alison Stewart: It rhymes with "grudge."

Victor LaValle: Grudge. Yes, for sure.

Alison Stewart: Mudges never forget.

Victor LaValle: That's right.

Alison Stewart: You're listening to my conversation with author Victor LaValle about his novel, Lone Women, from our May Get Lit with All Of It book club event. We'll have more with Victor and some questions from our audience after a quick break. This is All Of It.

[music]

Alison Stewart: You're listening to All Of It on WNYC. I'm Alison Stewart. We continue my conversation with author Victor LaValle about his gripping new novel, Lone Women. Victor joined us for our in-person Get Lit with All Of It book club event. Thanks to our partners at the New York Public Library, 1,751 of you were able to check out a copy to read along with us this month. As always, our audience had some great questions for Victor. You'll hear some of those in just a minute. First, more of my conversation about Lone Women with Victor LaValle.

[music]

Alison Stewart: All right. One of the things I mentioned to you earlier when we were talking in the back, I said, "Wait, Victor, is there anything you want to really talk about?" You said, "Usually, I can't spoil the novel." Since everybody's read it, we get to talk about-

Victor LaValle: I love that part.

Alison Stewart: -the back half of the book, which is exciting. The steamer trunk. How did you decide how long to keep us in the dark about what was in the steamer trunk or who is in the steamer trunk?

Victor LaValle: There were earlier drafts where almost immediately on the ship when they're going, it pops open, and Elizabeth eats a sailor, kind of thing. It felt too cheesy horror movie. There's a movie from the '80s called Creep Show. One of the stories in there is called, I think, The Box. There's a thing in a box and it's left under some stairs. It just starts eating people.

I love that one, but it's meant to be pulpy, silly. I said, "Well, let's not do that." Then I said, "All right. Well, if she's not going to jump out right away, then maybe there's some pleasure in not revealing it." Then I just tried to see how long could I not reveal it without it starting to be like, "I hate this guy." Because there was another time when I felt like, "What if you don't find out until the end of the book?" That would have been like, "I'm going to hit him." It was really trial and error.

Alison Stewart: Elizabeth is scaly and dragony and sometimes deadly. Did you have a picture of what Elizabeth looked like?

Victor LaValle: I did. Originally, I don't know if people would remember this, but in the '80s, there was a TV show called Land of the Lost with the Sleestaks. Originally, she, in my head, looked-- Who are they? They're like lizard people. If you ever look them up, the makeup actually looks amazing for the time. I imagined her a little bit on the head like that like Sleestak-ish.

Then I thought like, "Well, but we've seen Sleestaks, so I can't do that." I also wanted her to fly. Then our kids, especially our older son, loves dragons. Now, our younger son as well. Dragons are always in the house. They're always drawing dragons and all this. I thought about this idea of, "Well, to them, if they saw a dragon, it would be so much better than everything else life could offer."

Of course, if I saw a dragon, I think I would be horrified and run away. I thought, "Oh, that's a kind of creature or body that your perspective determines whether it's considered something good or something bad. Each of us will bring a different thing to it. In that way, I thought, "Oh, maybe that's interesting." She's almost dinosaur-like, dragon-like. We will get to see different people feeling differently about her when they see her.

Alison Stewart: We realize that Elizabeth may not be the only Elizabeth-like creature out there, but we don't really know the origin story. Do you know it? Did you have it? Do you have a backstory that [crosstalk] creatures?

Victor LaValle: I guess what I will say is-- so my family-- we have a number of people in the family who deal with varying degrees. Some really severe of what we might call mental illness or neurodivergence, right? It's one of my obsessions, I think, is the question of, "Why do some people come out one way and why do other people come out this other way?" There is no answer to that thing.

There is conjecture. There's this, there's that, but it is one of the great mysteries of certainly my life when I look at my family is the gamble of that thing, right? For me, as much as it is always unsatisfying to people, the answer is, "That happens sometimes and this is how people come out." Certainly, the point by the end of the story is it's only one's perspective that presumes that means it is a curse.

Other people will see that and say it's a blessing. Then there's a third option that says, "Oh, it's just run of the mill. It's just how they came out." That was my feeling of how much I wanted to-- as opposed to like you find out 500 years ago, dragon people came to earth from Venus or something. I felt like that's the surefire way for me to make this too goofy. To my mind, it was just a matter of like it's just an accident of birth.

Alison Stewart: How did you find Elizabeth's voice?

Victor LaValle: That was actually my editor, Chris Jackson. Her chapters originally were written just like everyone else's. His point was like, "That's boring, number one. Number two, it doesn't make sense," he was saying, "for someone who has lived so differently and who thinks so differently and who's in such a different experience. Why would they just come out exactly the same? Might there be some way that they see the world a little differently? Could you teach us that through how we just scan their parts on the page?"

I thought, "All right, so then maybe this is one of the moments where I get to give the heartbreaking insight that, in fact, Elizabeth is a complex thinking being with insight and beauty." To my mind, that only makes it more horrifying that that's how her family treated her because this is who was inside. I wanted it to feel poetic and beautiful and that, hopefully, it would only make your heartbreak more for her having lived 31 years treated like something inhuman or something monstrous.

Alison Stewart: What did you want to explore about violence in this book? Because things get pretty violent.

Victor LaValle: Things get pretty violent, yes. The first thing is as I was reading those newspaper accounts, what was regularly made clear was how absolutely violent this world was. There's a part, a portion of the way through where I list a few deaths. A child walks out of the house in the middle of a snowstorm and gets lost in the snow and essentially bleeds to death from the cold out there. A woman drinks. I forget exactly what it was. Now, I'm blanking on the exact thing she drinks.

The question is, did she try to kill herself or did she just, in the middle of the night, mistakenly drink this thing? It was basically like drinking acid. There was constant stuff like that happening. That boy dying was a real news story. The woman drinking that poison and basically bubbling her insides was a real story. The more I picked up, the more I was just like, "Oof, I actually can't write how rough this place is." In a weird way, I totally understand that it's a violent book, and yet when I finished it, I was just like, "I really held back compared to how things were."

Alison Stewart: Let's take some audience questions.

Audience Member 1: I've read all your books, most of them several times. What I feel about them is they're very cinematic. I guess my question is, do you see your books as films? If so, what director, Jordan Peele, would you work with, Jordan Peele, for your movie?

[laughter]

Alison Stewart: Jordan Peele.

Victor LaValle: For some reason, I'm thinking, "Jordan Peele."

[laughter]

Victor LaValle: Certainly, number one, thank you for reading all of them multiple times. Two, I do think there's a visual component. I don't think of them as films certainly, but I'm a very visual learner. I do think I default to trying to paint visual pictures as well as spending time inside characters' heads and all the rest. I hope that that comes across so that you can really feel like you're there and you can see these things and all the rest. If I believed that Jordan Peele would ever direct something he didn't write, then I would love it. I would be thrilled. From your mouth--

Alison Stewart: We put it out in the universe.

Victor LaValle: Yes, that's right.

Alison Stewart: There we go in the back.

Audience Member 2: Hi, thank you. This was a great conversation. I wanted to know, you spoke a little bit about what was the inspiration for setting up in Montana and what led you to write the story. Given that a lot of the writing that you've done has been in New York or, as you've mentioned, a version of Oakland, what was the process of writing in a place that might have been, at the very least, initially foreign like and how did you work through those challenges beyond the research of the gazette?

Victor LaValle: Actually, the funny thing is the gazette was the greatest gift for that. I got inspiration from, I think-- Is her name Lauren Hillenbrand, the writer of Seabiscuit, that I remember seeing a piece on her talking about she has, I think, an autoimmune issue that doesn't allow her to leave her home terribly much and go do research in the places she goes to. She's the one who talked about like what I do is I buy all the newspapers of that era and of that time and I just read them.

I don't read them just for the news. What are the advertisements? What are people buying these days? I read the death notices. Has there been a spate of children dying? Was there an illness that was local that maybe doesn't make the history books? In fact, reading the newspaper was, in fact, the greatest way for me to-- Like I said, I'm married with two kids. I was not picking up and moving to Montana anytime soon.

Certainly, my family did not want to go with me there. I was not going to be leaving my wife alone with the two kids. I think that was clear. I'm promising you. This was the next best thing. Reading those papers, it was fascinating to see over the span of five, six, seven years, you really do get a sense of when-- You can even see it. Right around 1916 is right when everything that's going to create the Dust Bowl is just starting.

1915, 1914, they're like, "This is the land of milk and honey. There's rain plentiful. The snows are good." You can just see the moment when everything tilts and then, all of a sudden, everything gets more desperate and all the rest. That really was the heart of that research, just reading that and starting to feel like I was really getting to know these folks on a minute level.

Alison Stewart: That was my conversation with author, Victor LaValle, from our May Get Lit with All Of It book club event. We spent the month reading his novel, Lone Women.

Copyright © 2023 New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.

New York Public Radio transcripts are created on a rush deadline, often by contractors. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of New York Public Radio’s programming is the audio record.