Frederick Douglass's Friends And Family

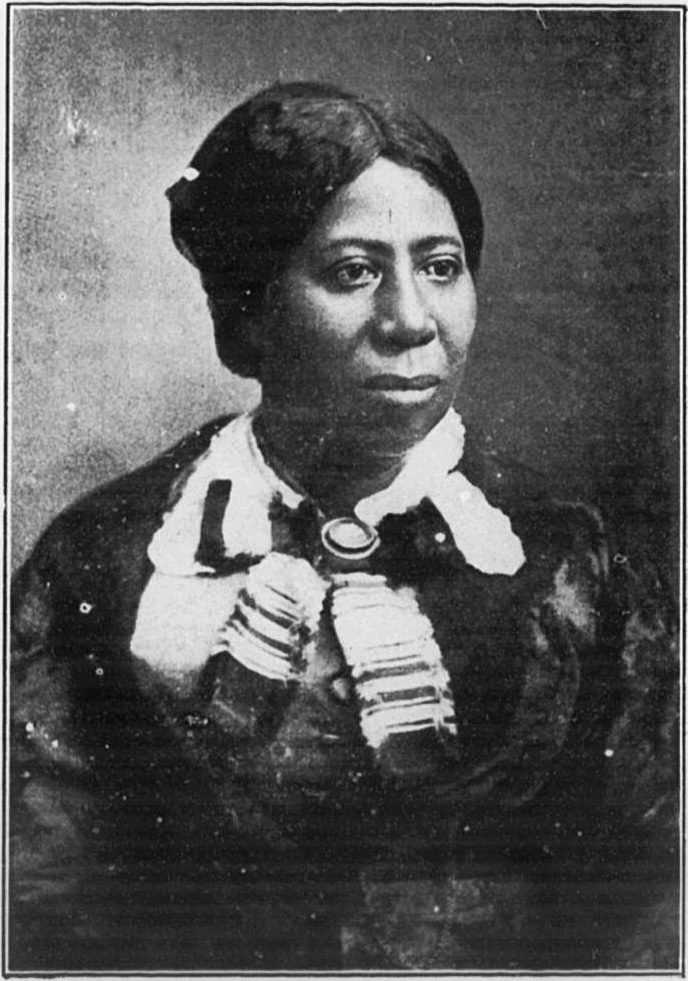

( Photograph first published in Rosetta Douglass Sprague, "My Mother As I Recall Her", 1900 )

[music]

Alison Stewart: You are listening to All Of It on WNYC. I'm Alison Stewart. Thank you for spending part of your 4th of July with us. Whether you're listening on the radio, live streaming, or On Demand, I'm grateful you're here. To give you a glimpse of what we have planned for the rest of the week, tomorrow, we'll hear from the lead of Shakespeare in the Park's production of Hamlet.

We'll also speak to the curator of a new Cooper Hewitt exhibition about the language and history of symbols, which, of course, is relevant to the 4th of July and the flag. If you missed any of our conversations live, you can also listen back on our podcast feed. For now, let's continue with today's full bio show dedicated to the life of abolitionist Frederick Douglass.

[music]

All day today for July 4th, we're discussing the life of a man who had a lot of thoughts about the significance of the holiday and what liberty means, Frederick Douglass. Our guest is David Blight, Professor of History at Yale University and author of Frederick Douglass: Prophet of Freedom. It won the Pulitzer Prize in 2018. We've arrived at the part of the story where we learn about Douglass's family life, which at times reads like a TV soap opera full of lawsuits, difficult marriages, and sometimes tragedy. His long time partner, his wife, Anna Murray Douglass, had five children with Frederick, but only four survived into adulthood.

Douglass was also insistent that his sons fight in the Civil War. His daughter married a man who didn't like Douglass at all, and even tried to publicly disgrace him. His wife, Anna, never really relied on Douglass for comfort and company because he was barely home. He found intellectual companionship outside of his marriage with several women. Douglass was a man of letters, but Anna couldn't read, and never learned. Yet still, their marriage lasted for more than 40 years. I ask David Blight about how Frederick Douglass met Anna, and why they decided to get married.

David Blight: He meets Anna probably when he was about 18 in Baltimore, could have met her even a bit before that. She was free, although they were born out on the Eastern Shore, probably only three miles from each other. When they met, we don't know, but I've always imagined they must have just started telling stories from the Eastern Shore. They probably played as children at the same mill on the Tuckahoe River. By then, she was three years older than Douglass, and she had a gig. She had a job working in the home of a well-to-do white family.

She got paid enough to make a living, but they fell in love. He was this strapping 18-year-old brilliant young guy. They might have met at church. They might have met even at a debating society that Douglass participated in. She was very involved, we know, in his plot of escape in 1838. Once they are out of Maryland, and into New York, and on up to New Bedford as we've discussed, here was this young couple. Began having children, and trying to make a home in this foreign world of the north and in a free Black community that they grew into very different people, says something about their skills, different skills.

It says a lot about gender. What options did an Anna Murray have? People have always wondered why she never learned to read and write. Everyone should be careful with all the possible speculations about that. The truth is we do not know why. What we do know is Douglass, their daughter Rosetta, who was their oldest and Julia Griffiths, for that matter, all tutored Anna. They tried everything they knew to teach her reading and writing, and it just never worked. For whatever the real reason, at the end of the day, we do know that Anna kept the bank book. She was good with numbers. She kept the accounts.

We know that from a reminiscence written by the daughter, Rosetta. Of course, early on in this marriage, each other was all they had. It was no doubt a deep and abiding bond. Then five children are born within the course of about eight years. The fifth one, Annie, Anna's namesake, would only live to be 11. She died of diphtheria in 1860 when Douglass was off in England, escaping after John Brown's raid. This is a family early, at least, that is going to have a lot of joy, but a lot of real hardship, and then tragedy as well. Anna's the one who kept the family together.

She's married to this growing intellectual, this man who's trying to read everything he can find, this man who is editing a newspaper, this man who is writing books, and essays, and editorials, and even one novella that the world is taking notice of. Who knows what Anna must have thought about this, but by the middle of the 1850s, she's married to the most famous Black man in the world.

Alison Stewart: He's on the road constantly. That's become--

David Blight: Absolutely.

Alison Stewart: very clear during the course of the book and, of course, their life, he is not physically present as a husband or a father. She's left on her own quite a bit. Did you get a sense from his letters, or why being physically with his family wasn't a higher priority?

David Blight: For one thing, it's the way he made a living. Being on the road, itinerant lecture, getting paid 50 bucks, a lecture, and by the way after the Civil War, he would make 100 to $150 a lecture. That's serious money, especially if you can go on the circuit and do 30 lectures in one trip. Part of that was making a living, part of that is using his voice. He had adoring relationships with all four of his surviving adult children. There's no question about that. We know that from the letters. He could be a very doting father in some ways. He was certainly a doting grandfather, later on.

He and Anna will end up with 21 grandchildren. That came from only three of the surviving adult children because Lewis, their oldest, never had children. He was terribly wounded in the Battle of Fort Wagner, in the Civil War in the groin, as they say, and could never have children. Family and home were extremely important to Douglass, but there's no question. I once tried to calculate, I never could really do it, but by using travel itineraries and so on and the average number of speeches and this and that, I tried to calculate for a decade or so how much time Douglass was actually at home, and how much he was on the road, and it just became hard to do.

What would be the conclusion if I had found that he was gone 60% of the time? I actually had interesting conversations with some women historian friends of mine. It was actually a year I spent in England at Cambridge where I wrote eight chapters of this book, and we had a lunch one day. There were three or four of us sitting around, and I asked them what they all thought of all this. They said, "David, don't be too hard on Douglass. This is what prominent men did in the 19th century. Think if he'd been in Congress, he wouldn't have been home much either. Think of senators, and so on, and so forth."

Of course, they were right, but I couldn't help thinking at times that this is a classic case of the absent father for those young people, the three sons. I suspect it was especially hard for the son. Later on, as I discuss in the book, it really some length. Douglass's three sons, especially two of them and his daughter Rosetta, all had difficult turbulent lives. Rosetta in part because she made a very bad marriage to a Civil War veteran, had seven babies with him in 12 years. That will lock up a woman's life in a hurry. Rosetta, by the way, had the best education of all the four Douglass children.

They even had a governess for her for a year. She went to a special school for another year. She tried to become a teacher for a while. Anyway, the Douglass children struggled to make a living, struggled with their lives, and even their own families. Of course, that doesn't make them that special. Lots of people struggle. I do think there's evidence in my book, and there's certainly evidence laying around out there that it was never easy to be Frederick Douglass's son and daughter. He became so famous. He had a real problem with fame or what we today would call celebrity. They didn't have that word then. Douglass by the time of the Civil War, and especially in the wake of the Civil War when his travels were safer, was recognizable everywhere. That has some pleasure, but it has some peril as well. He became eventually the sole financial supporter of most of this huge extended family by the 1870s. Only his oldest son, Lewis, by my calculations, was able to really develop an independent life. Everybody else was dependent on him. We know this because there are quite detailed account books, several of them that show how much money Douglass is disbursing for this and for that. It shows particularly how much money he is giving to directly to his sons, his son-in-law, and his daughter, and eventually even to his grandchildren.

Alison Stewart: Frederick Douglass had various relationships with different women, different levels of intimacy. Some of his relationships were professional. He was at Seneca Falls, he knew Susan B. Anthony. He had collaborated with Ida B. Wells during the course of his life. We mentioned earlier, Julia, you have a whole chapter, my faithful friend Julia, that's Julia Griffith, the British abolitionist. Perhaps the most curious is his relationship with, and I'm going to let you say her name because I'm not sure how to pronounce it.

David Blight: [laughs] It's Ottilie Assing.

Alison: Ottilie Assing, a German-born activist who moves to the states, moves to Hoboken, New Jersey, and essentially moves into Frederick Douglass's life. How would you describe their relationship?

David Blight: Turbulent, mysterious, and very difficult to explain. Of all the problems to solve in Douglass's biography, and there are several, it's trying to get to the bottom of and explain Ottilie Assing that was the most difficult of all. Ottilie Assing was a German Forty-Eighter. That means she was greatly influenced by the Republican revolutions of 1848. She was a German Jew, although not a practicing Jew. In fact, she was a ferocious atheist. Her father and her mother were writers and poets. In fact, her father had been imprisoned after the revolution of the '48.

She came to America in the early 1850s as a journalist. She was very well educated, extremely well read, fluent in at least three languages. She came to America to cover, as a journalist, the American anti-slavery movement. The slavery issue in America was tearing America apart in the 1850s. She began to read the abolitionist. When she read Douglass's second autobiography, My Bondage and My Freedom in 1855, she was knocked out of her shoes, so to speak. Less than a year later, she traveled out to Rochester, New York. Really, didn't have an appointment. She just went up to the Douglass home and said, "May I interview you?"

Then of course, he said, "Yes." One thing led to another, to another, but in effect, as you suggested, Alison, she tried never to leave. Now, their relationship would be roughly about 22 years, on and off, on and off. She lived in Hoboken, New Jersey, which was an enclave of German émigrés, particularly émigré writers, and artist, and a couple of scientist. She made a living in part through her journalism, but in part as a teacher. She wrote for a journal in Germany called [unintelligible 00:14:09], where she wrote regular essays, and we have all of those.

She would go out to Rochester where the Douglass's lived, and spend summers as a friend of the family. Now, we also know that Douglass visited Hoboken on his travels. If you traveled into New York City by train, and then traveled south out of New York City, you went through Hoboken. It was a main train depot. Now, she lived in a boarding house. She operated her own salon, she called it her gang. This was a group of anywhere from 5 to 10, mostly German émigrés intellectuals. They just thought Douglass was the coolest thing that ever happened.

He was this dashing, romantic Black American radical, and all of them were trying to be now newly formed American radicals. He would go, according to Assing, and spend a night or two there in Hoboken at various times. The problem with this relationship, there are many, but one of them is a source problem. Everything we know about the relationship, or let's say 95% of what we know about it, comes only from her pen, from her letters to her sister that she wrote back to Europe. Her sister, Ludmilla, lived in various parts of Europe. We have some of the letters she wrote to Douglass have survived. Not a single letter from him to her survived.

Alison Stewart: That's interesting.

David Blight: She burned them all, we believe. Now, we do know she wrote to him a lot because she's always saying, "I got your letter. I'm glad you said this. What about that?" Now, I could go on and on about this. Was it a sexual relationship? Probably. I can't prove even that. I have a colleague in this field whom I have enormous respect for, Leigh Fought, who wrote a book called The Women in the World of Frederick Douglass. It's a brilliant book. I highly recommend it. She doesn't believe it really was a sexual relationship. We've had wonderful fawn arguments about all that.

At the end of the day, it may not matter. What Assing was though, clearly again, not unlike Julia Griffiths had been, she clearly was an intellectual companion. Here's the problem. She was also, and it must be said as I say in the book, an extraordinarily difficult and arrogant woman. She hated Anna Douglas, and said so in these letters to her sister back in Europe. Said so in ugly language. She also was very critical of Douglass's adult children. Even though she became fairly close with them, she was always wrapping them in these private letters for being "leeches on their father," and so on, and so forth.

In effect, Assing, at least in these letters resented anybody that got between her and Douglass, son, daughter, wife, or anybody else for that matter. Even after Douglass moved to Washington DC in 1872 after his house was burned in Rochester, Assing still continued to visit in Washington. She would come and visit for three months at a time, and live in the Douglass home.

Alison: I've been speaking with historian David Blight about his biography, Frederick Douglass: Prophet of Freedom.

[music]

Up next, we continue with the look at Douglass's political life and his support for the Republican Party. Also, we'll speak about his relationship with Abraham Lincoln, and one terrible meeting he had with Lincoln's successor, Andrew Johnson.

Copyright © 2023 New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.

New York Public Radio transcripts are created on a rush deadline, often by contractors. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of New York Public Radio’s programming is the audio record.