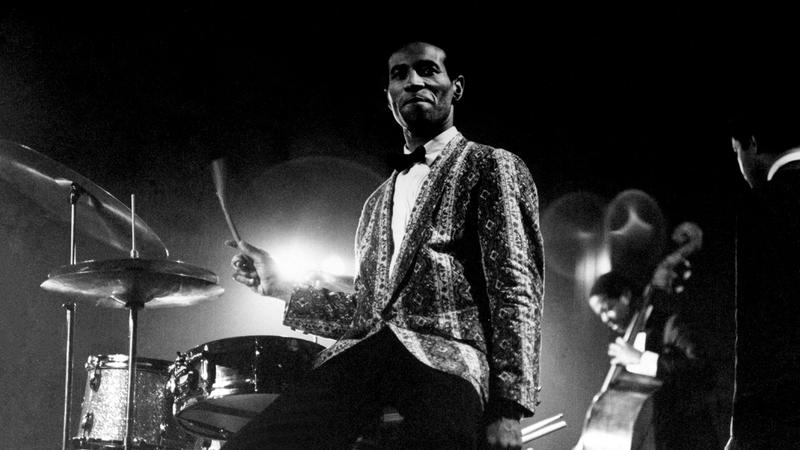

Drummer Max Roach Turns 100

( The Max Roach Collection, the Music Division, The Library of Congress / courtesy of Rooftop Films )

[music]

Alison Stewart: This is All Of It from WNYC. I'm Alison Stewart. Max Roach was born a hundred years ago today in coastal North Carolina. When he was a young boy, his family moved to Bed-Stuy, where he grew up playing music in the church. The legend goes, when he was 18, he was asked to step in one night for the drummer of the Duke Ellington Orchestra, and soon Roach found himself alongside some of the greats, like Charlie Parker and Dizzy Gillespie. Roach created his own lane. Re-imagining what drumming could be, he's remembered as one of the greats.

This month, there are centennial concerts planned, including two at Jazz at Lincoln Center, and also one at NJPAC. It's a modern take on one of Roach's most important works, We Insist!: Max Roach’s Freedom Suite from 1960 recorded with the exceptional singer Abby Lincoln, to whom he was married for eight years. Here's a composition from the album Freedom Day.

[MUSIC - Abbey Lincoln: Freedom Day]

Alison Stewart: This January 26th, the Freedom Now Suite, celebrating Max Roach Centennial Concert is happening at the New Jersey Performing Arts Center at 8:00 PM. Joining me now to celebrate Max Roach's Centennial birthday is Nasheet Waits, drummer and musical director of the NJPAC concert. Thank you for being with us.

Nasheet Waits: My pleasure.

Alison Stewart: And Raoul Roach, Max Roach's son. Nice to meet you.

Raoul Roach: Nice to meet you as well. Thank you so much.

Alison Stewart: Max, your dad was born in coastal North Carolina, as we mentioned, 1924. Obviously, it's a centennial. How did your father talk about Brooklyn, though? I think most people think about him and Bed-Stuy.

Raoul Roach: Well, he loved it. He continued to be connected to the community, which was most important to him and the Bed-Stuy community throughout his life. Working with young people, working with new musicians. I think he cherished and spoke often about, and I know a ton of stories, but stories from that era, but it's really what educated him. He started playing at Concord Baptist Church in Bed-Stuy, our family church for many generations and was a part of the drum and bugle corps. That's how he picked up his instrument.

Then he went on to just go to all the clubs as a young person, like 13, 14, sneaking in the clubs, and the club owners in Brooklyn would let him in so he could listen to all these great musicians. Very fondly, he thought of what he felt was not his birthplace, but definitely his home was Bed-Stuy, Brooklyn.

Alison Stewart: Was there any conversation in the family about, or any attachment to the South at all?

Raoul Roach: Oh, yes. We went there every two years. The great story about the South is my father's grandfather, my great-great-great-grandfather--

Alison Stewart: One of the greats.

Raoul Roach: Right. Founded a town Newland Township in 1840 before the Civil War. Black man who bought him his freedom and his wife's freedom and his brother's freedom in Barbados and immigrated to North Carolina. It's a very strange story but true. That town still exists. There's only two roads. It's a farm community. All of my grandmother's, my father's mother's family lives on one line, the Saunders and the other road is Roaches. We have a lot of double cousins.

Yes, they're doing a Max Roach Day down there. They're really bringing out the bells. They put up a mural and doing concerts and a series of lectures down there. Max Roach Day, and they're doing a Max Roach Festival in April, which there'll be details available on maxroach.com.

Alison Stewart: There you go. As an adult, do you have a sense of why your folks or your dad took you down there every couple of years?

Raoul Roach: Wow, that's such a great question. I think for him it was about connecting to community, about connecting to roots. Everything for him was about celebrating the ancestors. Whether that be in the South or in Africa, he developed that connection, studied that connection, and engaged with that connection throughout his life.

Alison Stewart: Nasheet, let's bring you in the conversation. Your father was a percussionist who played with Max Roach.

Nasheet Waits: It certainly was.

Alison Stewart: Yes, he was one of your mentors?

Nasheet Waits: Oh, definitely. The first mentor.

Alison Stewart: What do you remember about the first time you met Max Roach?

Nasheet Waits: I don't remember the first time because it was like he was a member of the family from the--

Alison Stewart: He was just always there.

Nasheet Waits: Yes. It was like he was a member of the family from the beginning, to be quite honest. I took a lot of those relationships and opportunities for granted as a younger person. As I get older as I am now, I realize how precious that opportunity was.

Alison Stewart: As you think about it as a professional musician, when you think about what his contribution has been and what made him unique, those are two different things. What made him unique? Then when you think about what his contribution was to drumming.

Nasheet Waits: Well, I think they actually come hand in hand because what made him unique was also what he contributed. What made him unique was not something that is unique. It's like a consistent work ethic. Also, somebody who is dedicated to pushing the envelope and never resting on their laurels. There were a lot of musicians who were like that. In the world of "drumming", he's tantamount to other drummers. They look to him as like the top of the mountain because of the type of time that he put in to his work and the fact that he was dedicated to an original connection to the creative source. He preached that nonstop.

Alison Stewart: Something so interesting you said, and it just sort of, it blew my mind for a minute. When I think about someone like Matt Rubin, when I think about Matt Rubin, I think talent, and I think about the creative spirit, but you talked about the hard work he put in the time. Raoul, could you speak to that a little bit about the idea of, you can have all the talent, you can have all the passion, but man, it comes down to work.

Raoul Roach: Absolutely. He believed in it. Trust me, me and my siblings-

Alison Stewart: [unintelligible 00:07:20]

[laughter]

Raoul Roach: -all of us started working as soon as we could. He put us to work. Yes, absolutely. He had a work ethic and he believed in the work ethic. Even though he had genius and talent and imagination for days, beyond, it really was about putting in the work and about expanding the boundaries. His whole thing was not being locked in as a drummer, as a timekeeper, not having a frontline and a back line, but making bebop, what they call bebop music, about working together with equals.

Everyone had something to say, a very democratic art form, as he would say. The work to him, it was the most important thing, I think, in his life following his muse. Then everybody else came next, including his family. He loved everybody, people and his family. Absolutely.

Alison Stewart: We are discussing the centennial of Max Roach. He would've turned 100 today. There are all these Max Roach centennial concerts, this one happening at NJPAC on January 26th at 8:00 PM. My guests are Nasheet Waits and Raoul Roach. Nasheet, you chose a song for us to hear, you wanted us to play Equipoise from 1968.

Nasheet Waits: Oh, that was Raoul's choice.

Alison Stewart: That was Raoul's choice.

Nasheet Waits: That's a beautiful song. Stanley Stanley Cowell composition. Wonderful.

Alison Stewart: Raoul, why did you choose this one?

Raoul Roach: During that period is when I began to come and spend more time with my dad, with a musician who's on the road all the time, and one-nighters. I experienced that young. After I came out of college, I was Wynton Marsalis's road manager for a brief period. After six months, I was ready to stop. It's a hard life. Yes, I'm going to be an executive. Sit in a room and use my pen. That's it. I think that what was important to him was making sure that he wasn't put in a box, the box of jazz, the box of drumming, the box of being a Black man, the box of anything he wanted to expand the boundaries. It was about freedom for him.

Alison Stewart: Let's hear Equipoise.

[MUSIC - Max Roach: Equipoise]

Alison Stewart: Nasheet, what is something that you hear as a drummer about this technique and this song that you want people who aren't drummers to understand?

Nasheet Waits: There's always a commentary on texture. The juxtaposition of smooth and rough to just use layman's terms so everybody can understand it. Also, a sense of time and how you can feel different parts of the beat before, the after, the middle. Also, dynamics in terms of how you accompany a melody, how you accentuate certain passages in that melody. All of that is present and what Papa Max was doing right there.

Alison Stewart: We're discussing the centennial of Max Roach. We'll have more after a quick break. This is All Of It.

[music]

Alison Stewart: This is All Of It on WNYC. I'm Alison Stewart. We are celebrating Max Roach. He would've turned 100 today. It's his birthday. Joining us in the studio is his son, Raoul Roach, as well as Nasheet Waits, another very good drummer who was also Max Roach was his mentor and friend of his family. I want to play a clip, Raoul, of your dad. Because your dad was not fond of labels. You alluded to that about boxes. He didn't really like the term jazz or bebop. This is the clip of him speaking about this, which was featured in a recent PBS documentary about him.

Max Roach: Well, jazz is, to me, a nickname. To me, it's synonymous to [inaudible 00:12:30] and things like that. That's not the proper name for African American instrumental music. It never was a name that we as musicians gave to. It was a name that just was given to him.

Interviewer: You're not a jazz musician?

Max Roach: No. I'm an African American musician, and that's the kind of music that I play.

Alison Stewart: What do you make of your dad's thoughts about that now that you're a person who's been in the music industry? Same for you Nasheett, you're a musician yourself. How do you relate to that thought process?

Raoul Roach: I think, it's tantamount to talking about not being labeled, not allowing other people to define you, but defining yourself. Essentially, that's a core principle of freedom, is the ability to do that. I think that statement embodies that.

Alison Stewart: How about for you, Nasheet, when you think about the labels we put around music?

Nasheet Waits: Well, I remember Max specifically commenting on that very word and his sentiment was jazz as a four-letter word. He said, "Every time I use that word, when I'm negotiating a contract, the money goes down." Could be the same project, could be the same music. There was a negative quality that was associated with the term that also, encapsulated in that is also the racist, the racism and any other isms that you would negatively categorize a people or a source of a culture, which is what that is. He was definitely against that word and that label and what it represented. Because like Raoul was saying, it had a way of limiting the opportunity.

Alison Stewart: I've heard it from modern jazz musicians as well, that the label is not something that they want to be associated with. That they want to be musicians.

Nasheet Waits: It wasn't originated by the creators as well. That's another position that he was firm about because it didn't have a representation of the people who were creating the culture, who were from the culture. It was created by people who were on the outside looking in and finding a way to monetize it.

Alison Stewart: Commodify it.

Nasheet: Yes, exactly.

Raoul Roach: He talked about the etymology of the word jazz was a slang word in New Orleans that meant sex. At that time, our music, beside us playing it for ourselves, was only played, you get paid for the Black musicians who played in the houses of ill repute in New Orleans. They would call it jazz music because these were jazz houses of sex. Once he found that out, he understood that this was really something that was named by outsiders, their experience with it, and not by the creators of it.

Alison Stewart: The story goes, the big break came at 18, and he filled in as a drummer one night for the Duke Ellington Orchestra at the Paramount Theater. To put this in context for people, Nasheet, as an 18-year-old kid, a drummer, what would that mean to a young drummer?

Nasheet Waits: Everything. Because Duke Ellington, he's the ambassador. At that time, he's a star. One of the preeminent faces on the planet. Much less in the music. For him to get that opportunity is commend on his preparedness because he wouldn't have got the opportunity if he wasn't ready to shine. From that, he just said he took off. From before that, he was already ascending, but then when you get those opportunities, he took full advantage.

Alison Stewart: Did he ever talk about that night with you, Raoul?

Raoul Roach: Yes, he talked about it a lot. He had, of course, he had a story. He said that his drummer, Sid Catlett, I think, was drafted. He was in New York, and he called the club owner in Brooklyn, a friend of his, and asked, "Do you know any drummers who can read music?" He said, "Well, I know a kid. He sounds great." Then recommended Dad. He said he showed up.

When he got to the bandstand and he sat up high behind, above the band. He got to the drums and there was no music in sight. He was freaked out. [crosstalk] Then Duke was, of course, these guys are so sensitive and smart and prescient. He looked at him and saw his panic and said, "Don't worry. Keep one eye on the act and one eye on me, and you'll do fine." He said he made it through.

[laughter]

Nasheet Waits: That's incredible. That's right.

Alison Stewart: We are discussing Max Roach. Today would've been his 100th birthday. My guests are Nasheet Waits and Raoul Roach. We're going to play a song. Raoul, what do you want people to know about this song?

Raoul Roach: My dad recorded this in a session with Clifford Brown five months after I was born. It didn't come out on the original release. It came out as an alternate take in a later reissue of the record in the early '60s. I never knew about it until I got older. When I think about it now, I just think about the fact that it was Christmas time and he loved me, and he thought about me, and he recorded a song after me. I'm very happy about that.

Alison Stewart: Let's hear it.

[MUSIC - Max Roach: Raoul]

Alison Stewart: That is Raoul. Of course, we mentioned in the intro, We Insist!: Max Roach’s Freedom Suite now released in 1960. Y'all are reimagining it for this concert at NJPAC, Cassandra Wilson's going to be there, Ravi Coltrane. Tell us a little bit more about this evening. What were your hopes for it? What are your dreams for it?

Nasheet Waits: My hopes and dreams are that we're able to make an offering that is well received by the people. Some incredible musicians like Cassandra, I believe this is going to be the first time she's going to have performed live in some years. It's really special for us. We're very grateful that she agreed to be a part. Ravi Coltrane is going to be a part of it as well. Nduduzo Makhathini playing piano, Eric Revis, bass. I could talk about everybody, but it's a long list of folks and whatnot. Then there's also going to be the addition of Sonia Sanchez and Saul Williams-

Alison Stewart: Oh, wow.

Nasheet Waits: -as dealing with the spoken word and Alyson Shotz offering the video, so reimagined in a sense that that wasn't a component to the recording that was offered in 1960. Max reimagined this piece quite a few times after that, and there was some transcript involved and there were some choirs and dancers involved. It's been expanded several times. This is just another rendition.

Alison Stewart: When you think about this being your father's 100th birthday, his centennial, what is something you'd want people to know about him as a man and as a father? We can watch documentaries about him as a musician. We can hear his musicianship. As a person, something you'd like people to know about Max Roach?

Raoul Roach: I got to tell you, I think he was such an incredible person. He was brilliant, he was smart, he was ferocious and fierce in his determination and his drive to stick with his muse and make things happen in the world. My brother often quotes him as saying, "It's hard out here." He worked hard to make things happen. As a father, I think a traveling musician, it can be difficult. For my older siblings, he was out all the time.

Thelonious Monk's son told me that Dad told him, he was another student of Dad, that before Clifford Brown died, they had 400 dates booked over the next two years, so he was always away. When I came to live with him full-time because I lived with my mother, as my older siblings did, and he married my twin sisters, Ayo and Dara's mother, he took the professorship at the university. I got to really see that part of him as a father every day, and so did my younger sisters. It was wonderful.

Alison Stewart: The concert is on January 26 at 8:00 PM. It is the Max Roach Centennial concert happening at NJPAC. My guests have been Nasheet Waits and Raoul Roach. Thank you so much for coming to the studio. We really appreciate it and sharing your stories.

Raoul Roach: Thank you for having us.

Nasheet Waits: Thank you so much for having us.

Alison Stewart: Let's go out. Happiest time.

Raoul Roach: Yes. 100.

Alison Stewart: Happy birthday, Dad.

[music]

Copyright © 2024 New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.

New York Public Radio transcripts are created on a rush deadline, often by contractors. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of New York Public Radio’s programming is the audio record.