'Death Is Not the End:' The Rubin's Look At The Buddhist and Christian Art Of Death

( Courtesy the Rubin Museum )

[music]

Alison: This is All Of It on WNYC. I'm Alison Stewart. We continue our conversation about the end of life with an exhibit that investigates how different cultures present death in their art and artifacts. It's at the Rubin Museum in Chelsea and the show is titled Death Is Not The End. For those unfamiliar with the museum, the Rubin is dedicated to showing the diversity of Himalayan art with a collection largely focused on Tibetan work inspired by Buddhism and Hinduism. For this show, the exhibit also brings in Christianity and its traditions to explore the story.

Visitors are greeted with this introduction. Both Buddhist and Christian cultures embrace the certainty of our mortality in this world while also proposing an existence after this lifetime. There was a promise of a better place even if this requires further purifying suffering to ensure the eventual attainment of a better existence. These views in their most general sense refute the permanence of death while accepting its inevitability. Death Is Not the End spans 12 centuries and consists of artifacts, paintings, books, and objects, plus a few interactive stations that allow viewers to express how they think about life and what comes after it.

Elena Pakhoutova is a senior creator of Himalayan art, and the organizer of the exhibit Death Is Not The End which will be on view through early January 2024. Elena, thank you for making time today.

Elena: Thank you for inviting me. It's great to be here and amazing too.

Alison: Listeners, at the end of this exhibition people can respond to four prompts, and you can write them out on cards and the answers are displayed on a wall so we thought we'd pose these questions to you if you want to call in. Describe your perfect afterlife, how does believing or not believing in the afterlife impact how you live, tell us how death might not be the end and what is rebirth to you. If you go to our Instagram @allofitwnyc. You can see what it looks like and some of the responses people have left. I took a bunch of pictures. You can respond there, or you can call in, 212-4339-692. 212-433-WNYC. Describe your perfect afterlife, how does believing or not believing in the afterlife impact how you live? Tell us how death might not be the end and what is rebirth for you. Elena, how did the show come about?

Elena: Well, I always think of universal frameworks in which to contextualize and present Tibetan Buddhist arts and showcase the Rubin Collection in the broader framework of art from other cultures. Given the current time of global turmoil, uncertainty, tremendous loss of life during a pandemic which still may be ongoing, we just felt that this was the time when we should address these questions in some way. Instead of focusing on death and its finality, which I think is basically the dead end, we could offer a different take.

Tibetan Buddhist culture in general is quite complex in its symbolism and meanings represented in its traditional art forms which comprise the majority of the Rubin Museum's collection. Christian culture is the most familiar to most people in the United States so it makes sense for the Rubin to explore these notions of the afterlife within these two frameworks.

Alison: When you go in and you read the text, it suggests that by considering both of these traditions, it can help broaden one's perspective. Just for people to get a sense of what the show is physically like, what is a piece from the show from each tradition that might broaden one's perspective?

Elena: Well, that depends on the visitor. Wouldn’t it? Tibetan Buddhist traditions present a very long perspective on existence that goes beyond just this life so are the various traditions of Christianity. Well, one example would be a Buddhist painting called The Wheel of Life from the museum's collection which is a vivid reminder of the endless cycle of life and death driven by desire, attachment, and endurance. It depicts six realms of existence where one can be reborn. Even if someone is fortunate, and have a very good birth right now, the karma of living that life is going to run out and one can be reborn in an unfortunate state of existence as an animal or human in hell.

The wheel also reminds me of the way to break the cycle and become free from it through cultivating an understanding of how this process works. For someone unfamiliar with the Buddhist view on existence, this could be a fresh perspective. It's a very long view on life. Then, for people who are not familiar with Christian tradition, another example that makes one thing about existence that comes after human life is uniquely composed, eliminated page from a book of ours which depicts the parliament of heaven. It shows divers two portal events for contemplation.

In prayer, there's God the Father on the throne who is about to send Gabriel to tell the Virgin Mary she will be mother to the savior of humankind and then there's Christ depicted as a child and then God's feet waiting to be sent to be born. The just souls of those people who are stuck in limbo, it’s shown actually as a prison cell there, they wait and have been waiting for a really long time they are released by Christ who is yet to be born. Then also there's Evangelist Luke who writes the gospel lesson. The most interesting part of his depiction is the Heaven itself which is actually empty of humans. It’s in waiting for these events to occur and receive humans. Even people who are familiar with Christian tradition and depictions of, let's say the Last Judgment and so forth, may find this quite fresh as well.

Alison: Let's take a call. Norbert is calling from Rockland County. Hi, Norbert, thanks for calling All Of It.

Norbert: Thank you, Alison. I tried to get through to Michael Caine. I am religious but I don't believe in an afterlife. I think it's closer to what Wolf Blitzer signs off on every day, and may their memory be a blessing. I think dead people stay dead, no exceptions but here's the counter thought. I'm going to be 80 in February and only so many shopping days left. I tell everyone about that but this upheaval when you realize it's a limited engagement. There's so many days you get and no more. Scars, allow thoughts to come in. I'm speaking with my father regularly, and he died at 70 in 1982.

There's something there and maybe in medieval times as your guest is too eloquently saying, people concretize it. They took things more literally, everything, heaven, hell, the devil satan, but maybe there's realities behind these things. That's my comment.

Alison: Norbert, thank you for calling in. Yes, Elena. There's a moment in the exhibition which asks and suggests that we need to think about what we're doing in this life at this moment what is important while we are living before we reach the point of death. Why did you want to include those: I think specifically of the painting of the woman that's half a woman and half a skeleton. Would you share a little bit about that painting?

Elena: Yes. This painting is actually quite interesting because it's not religious in nature. It shows as you just described a woman who is divided in two halves. One is very luxurious and beautiful, she has beautiful hair, a fancy dress, and there are a bunch of flowers blooming which symbolizes life. In another half there's a skeleton is the broken candle which symbolizes the extinguished spirit, and so forth. These paintings were meant to be used for contemplation at home. They would be hung at home so people would just be reminded of being aware of your own life and actually leaving well. This may be dovetails to what the previous caller was just talking about.

Alison: We're discussing the exhibition Death Is Not The End, it is at the Rubin Museum, I'm speaking with curator Elena Pakhoutova. I mentioned those four questions. There have been some terrific answers at the museum. One says have described your afterlife as being a tree that gets to live and decay in the forest either that. One says, how does believing or not believing affects you in the afterlife? It allows me to live in this moment now. Some of these answers are so beautiful, I'm wondering how you came up with those four questions.

Elena: Oh. Well, we had an internal discussion for a while about what to ask because we wanted the visitors to have some kind of opportunity to respond to all of these themes that they've experienced through looking at the art. These four questions, we had actually very many. We asked our staff to submit questions that they think would be good things to ponder on the exit from the exhibition. These four we combined and solidified many of the themes that were expressed.

Alison: Someone wrote on the card, tell us how death might not be the end. Everything around us, including ourselves, is made of energy so it stands to reason that when our energy meets death, that it would transfer to future creations of energy. People have written some really, really interesting things. I'm curious about-- We talked earlier with our guests about how people are frightened to talk about death and grief. Where is fear represented in the exhibition? Because that's a real thing for people.

Elena: Fear in the exhibition is part of the section that explores the human condition because it's something which is inevitable. Perhaps the idea of that there is something after is driven by the desire to continue to exist. Fear in some cases helps us to live better, in some cases may spur us to do something about it. I think human agency is a really important factor. Even if you just look at these paintings and sculpture and all these other objects on view, people spend a lot of time crafting them, painting them in meticulous detail.

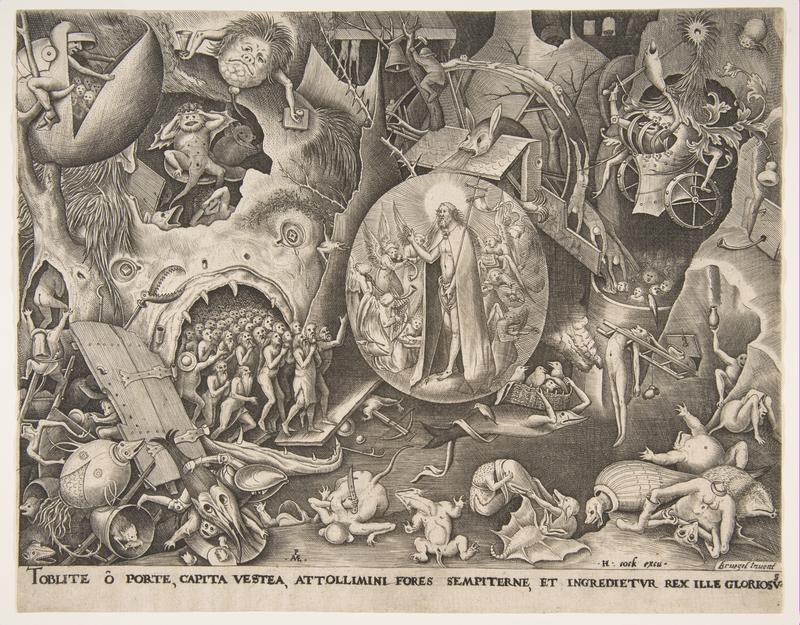

There are some images of horrifying scenes where the devil consumes the souls of the damned. The person who depicted it did an amazing job. There is a beautiful full-page illuminated manuscript that shows horrifying scenes like that. While you do that, you're actually contemplating these ideas. You are so focused on depicting it. It is some sort of meditation, I would even say.

In Tibetan Buddhist tradition also, the fear can be conquered through wisdom. Understanding the nature of your existence is one of the things that helps us overcome that fear.

Alison: Let's take a call from Sally calling from the Upper West Side. Hi, Sally, I have about a minute for you.

Sally: Yes. I said to the screener, when a very good friend of mine whom I was quite close to died back in the '90s, before the AIDS cocktail exhibited or was created, his doctor sent me a note and explaining that he agreed with me that there are no words that can mend the loss. He was Italian and he quoted from a verse from Horace that I found very helpful. Horace, translated into English, says, "I will live forever if you will want to remember me forever." I found that very comforting and I passed it on to a lot of friends.

Alison: Sally, thank you so much. Before we go, I wanted to mention that the last piece is this big, beautiful piece of Buddha in paradise. Why did this feel like the right last piece, Elena?

Elena: It's a very good question. Because we wanted the visitors to leave with a sense of hope and that offers this kind of imagined paradise or pure land of the Buddha, where people can be reborn in the presence of the divine and have no suffering and have a good life.

Alison The name of the exhibition--

Elena: You can also wish for your loved ones to experience that as well.

Alison: The name of the exhibition is Death is Not the End. It is at the Rubin Museum through January 2024. It is quite elegant and beautiful. My guest has been Elena Pakhoutova. She is the curator and the organizer of this particular exhibition. Elena, thank you so much for making time today.

Elena: It's my pleasure. Thank you for having me and sharing the exhibition with your listeners.

Copyright © 2023 New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.

New York Public Radio transcripts are created on a rush deadline, often by contractors. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of New York Public Radio’s programming is the audio record.