'Cycle of Creativity: Alison Saar and the Toni Morrison Papers'

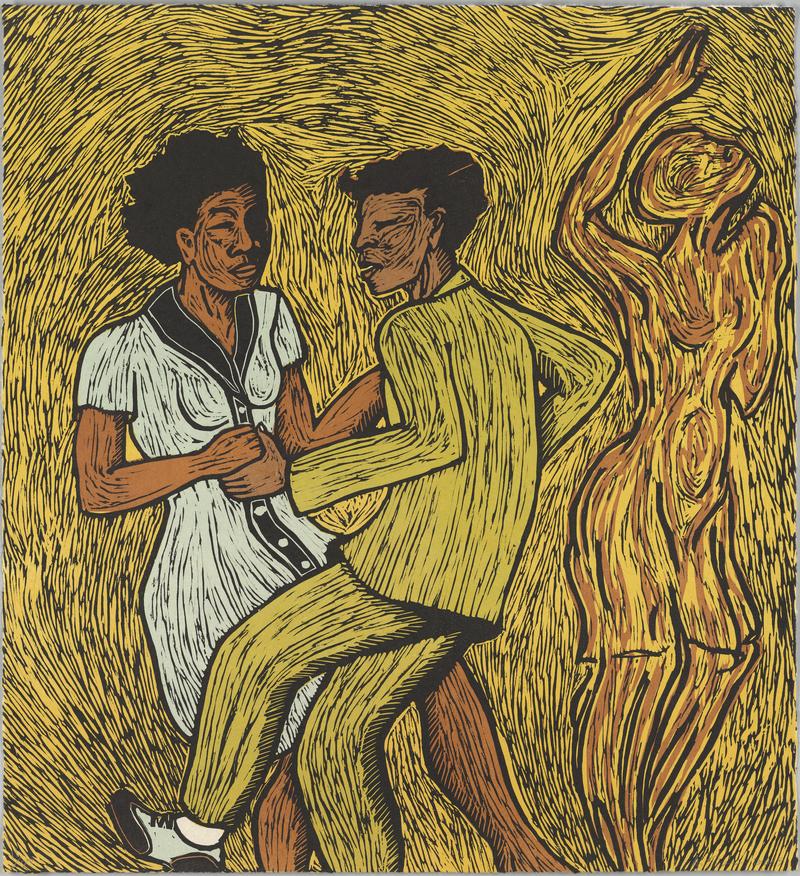

( © Alison Saar / courtesy of L.A. Louver, Venice, CA. )

[music]

Alison Stewart: This is All Of It. I'm Alison Stewart. Tomorrow the Princeton University Art Museum is opening an exhibition titled Cycle of Creativity: Alison Saar and the Toni Morrison Papers featuring the work of the LA-based artist, Alison Saar. Saar's work often represents and explores Black identity in the context of American history. She's the sculptor behind the statue of Harriet Tubman on a 122nd Street, the first Black woman to be commemorated with a public sculpture in New York City's history.

She created that Lorraine Hansberry piece that was in Times Square and is now at the Brooklyn Academy of Music where one of Hansberry's plays is being staged. Cycle of Creativity is on view at the Princeton Art Museum until July 9th and joining me now is Alison Saar. So nice to meet you.

Alison Saar: Thank you, Alison. It's nice to have a fellow Allison [unintelligible 00:00:56].

Alison Stewart: And spelled the right way. The title is Cycle of Creativity. What are you trying to communicate with this phrase, this is a phrase you've used before.

Alison Saar: Yes, and I think this is something that both [unintelligible 00:01:14] and Autumn connected with in terms of just really how I think both Toni and I are looking to the past while addressing the present and looking towards the future. I think that these things come up over and over again, and unfortunately, sometimes they're feeling like we're playing the same record over again. We were re-experiencing some things that we thought were done a while ago. I think also I was really interested in this idea of creating and making, and it's really lovely to see my work alongside the manuscripts of Toni Morrison and to just really understand what goes into crafting something.

Alison Stewart: When you were thinking about pieces to choose, if you would share an example with our audience of a piece that you chose that's in conversation with something from the archives.

Alison Saar: I haven't personally had access to the archive yet, and I'm looking forward to coming out to see it. Just in terms of looking at her work and a lot of things connect. In the book Jazz writing about Harlem and of course Harlem was a really big part of my development. I moved to New York in '81, '82. I think some of those places there's kind of connections. I think those jazz pieces, the dancing prints, and stuff like that really kind of connect with her work in that respect as well.

Alison Stewart: You didn't just move to Harlem, you were an artist in residence at the Studio Museum in Harlem, which is fantastic. It's just a wonderful program. When you think about that time, how did the energy of that neighborhood inform your work and impact your work?

Alison Saar: It was interesting because growing up in Laurel Canyon, which is probably as far from Harlem as you can get both through mileage and culturally, it was really interesting coming to a place where-- I was a really always intrigued with all of the art and the music that has come out of there historically. To actually be in the thick of it, it was just really incredible. It's just a really charged energy, and I love the people on the street. It was just really incredible. It was really invigorating to be in that place at that time just coming out of getting my MfA and just uprooting and coming to Harlem. It really was, I think, really meaningful in terms of the development of my work.

Alison Stewart: My guest is Alison Saar. Her work will be on display at Princeton University Art Museum as part of Cycle of Creativity: Alison Saar and the Toni Morrison Papers. The pieces and the exhibition, are they line of cuts? Am I using the right language?

Alison Saar: Yes.

Alison Stewart: Tell us a little more about the technique and when you started using it and what it allows you to do.

Alison Saar: Right. I think because I'm a wood carver, as a sculptor I just chose the tools that I had access to and wood was something, especially when I was living in New York, I could just grab off the street. I think my first woodcuts were made out of drawer line pieces of drawers and ship row that we busted up. I had been doing woodcuts for a while, and then when it came to doing this project, which actually originally was part of the Metro Transit Authority, Metro North train station commission that is also in 125th Street in Harlem. It's basically just cutting, and each of those prints are four blocks, three to four blocks.

Each color represents a different block. I think to do the entire series, I had carved over 64 blocks, which is a lot of blocks. The reason behind that was I think from the time I was at the Studio Museum in the early '80s to coming back in maybe like 2007 up until the present and visiting how much the Harlem had changed. All of my favorite soul food restaurants were gone, and all my favorite storefront churches had moved on. It really was painful to see that so much history is being erased. I really wanted to document that sort of heyday of jazz in Harlem and where every corner had some amazing club going on. That's really what that series came out of.

Alison Stewart: My follow up on that is there's music is a consistent theme in some of the work. One, do you listen to music when you are working?

Alison Saar: I listen to music, yes, when I'm working and a lot in general. Even if the imagery isn't music, often the titles are drawn from music. Yes, it's just really powerful. I view it as a form of poetry. I view it as a form of resistance. Music's a huge part of my process.

Alison Stewart: My guest is Alison Saar, the artists. We are talking about her practice as well as the exhibition Cycle of Creativity: Alison Saar and the Toni Morrison Papers. Do you have a memory of when you first read Toni Morrison?

Alison Saar: Bluest Eye was probably my first encounter with her. I was probably 18, 19 just a freshman in college. Yes, just really powerful. It's a painful book. I think again, that's somewhere I feel like she gives me the courage to talk about really painful things and through all of that to bring a sense of hope. That seems kind of contrary, but I think it's something that she does really well.

I would say just starting with that book which you were talking about you had mentioned to Autumn it's something that you would read differently after the pandemic. Think about reading something some 30 to 40 years later as an adult, and I need to actually, this has been inspiring me to go back and reread all those books because I think we always perceive something from that moment that we're in and so eager to revisit actually a lot of these works especially after seeing them in their formation through the archives.

Alison Stewart: Do you have that sensation or that experience with your own work when you go back and look at something you've done a long time ago?

Alison Saar: Absolutely. Yes, I absolutely do. When you're making a piece, you always think it's about something. Then I think as you get older and more mature and you've experienced more you realize maybe it's not just about this or maybe it wasn't ever about that. I think when I had my first child, I made a piece and now that my kids are 30 and 33, I go back and look at those pieces and like, oh, but this could also talk about something completely different not about child rearing or anything. It could be talking about, I don't know, the ballast in life and all of that. I think that's what's beautiful about art and literature and music that it means different things at different times just in terms of what we're bringing to it.

Alison Stewart: When I was speaking to Autumn earlier, I asked her about the research process and Toni Morrison's research process because it was interesting to see and to read about some of the things in the archives. The idea she looked for maps where the Underground Railroad was in Ohio, the way that she informed herself. When you are thinking about history and using history in your art, what is your research process and what are you drawn to in history?

Alison Saar: I think that's what's so important about showing what goes into these pieces because I always had this idea that oh, writers were just so fortunate they could just pull this stuff out of the ether, and there is done, and they didn't have to have chisels, they didn't have to have a massive studio and all of that but to be able to witness the process and all that goes into it in terms of researching. I think it relates in a lot of ways, when I'm carving I'm using a large block of wood, and I'm just carving it down until it gets to where it needs to be. I think maybe the writing process, I now recognize that the writing process is similar that you're constantly hewing it down to something until you get it to where you want it to be. For me, it usually starts with an idea. A lot of looking up roots of words, a lot of again, looking at botanical books, and looking at farming manuals, also looking at slave Ledgers. enslaved Ledgers. I think we're probably doing a lot of similar research, even though the work is very different that all these ideas are solidified by having this information behind it.

Alison Stewart: Is there a piece or one or two pieces that you would like people to spend a few extra seconds in front of in this exhibition cycle of creativity Alison Saar and the Toni Morrison papers or one that maybe excites you that it's part of this?

Alison Saar: Well, I think at the Peace Torch Song, which is a female figure, holding out her hand with the flame in her hand, and then she's wearing basically piano keys almost like Bandoleros, like bullets across her chest. Really, the idea came from listening to music, blues, whatever you think of Bessie Smith, and how these are often viewed as being torch songs traditionally, like romantic songs or whatnot but really beneath that there's songs of resistance.

I really love this idea that this was music for the battlegrounds. I think that was a lot of music I was listening to again, over the past three years, and how it really helped fortify me and helped me get through some of these very dark days we've been experiencing. I think we're going to be able to have some music that inspired me in the gallery when people are visiting. I'm hoping people, a lot a little bit of time to just sit and listen to the music and listen to the lyrics or think about what music has meant to them and to take that piece in and then be able to step out into the fray again.

Alison Stewart: That piece's Torch Song that we've been talking about. I did want to ask about the Harriet Tubman statue at Harlem in 122nd Street. As I've mentioned, first Black woman be commemorated in a public sculpture in New York City. Somebody asked me this question recently. I had to think about it for a while. I'm going to ask it to an artist is, why is public art important?

Alison Saar: Oh, gosh. I think public art when it really works is when it somehow engages the public to somehow rethink what they're doing and what their experience is. When I was invited to submit my designs for this, I was really excited that Obama had just been elected president and it felt to me that it was a time of change. I was also really intrigued. We all have a very limited notion of Harriet Tubman. I know as you know, the conductor of the Underground Railroad, but she was so much more.

What I really wanted to talk about in that piece, and share with people that are walking up and down at 125th Street walking down St. Nicholas, is this idea that this was a woman who couldn't read or write, had a disability in terms of that she was prone to seizures, and she was able to just do so much and give so much as she continued to give throughout her life and to just ask people to take a moment to think about what small thing can they do, whether it's donating money, whether it's donating time at a library to read the kids or picking up trash off the street, what small thing can each of us do to make this place a little bit better?

It's a sculpture of Harriet Tubman, but it's a sculpture about compassion. I think public art can do that and that is just kind of people are able to go in there that doesn't cost them anything. They can just sit and look at something, and it can bring to them whatever they need. I'm hoping that's my goal for public art in the future. It doesn't always do that.

Alison Stewart: I love the idea that someone can happen upon it and it can change their day.

Alison Saar: I love that she's become like this meeting place. People or groups gathered there for-- just friends meet there or large groups there. I think it's been the source of the women's labor march a couple of times. I love that it becomes a landmark. It's very exciting for me. I'm very thrilled that she's able to go beyond my limited ideas and making her and become something else in her own right.

Alison Stewart: My guest has been Alison Saar. You can see the exhibition cyclo creativity, Alison Saar, and the Toni Morrison Papers, starting tomorrow at the Princeton University Art Museum. It will be up through July 9th. Alison, thank you so much for spending time with us.

Alison Saar: Thank you so much, Alison, for having me. Talk to you later. Bye.

Copyright © 2023 New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.

New York Public Radio transcripts are created on a rush deadline, often by contractors. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of New York Public Radio’s programming is the audio record.