'Blindspot' Podcast Revisits the HIV/AIDS Epidemic

[MUSIC - Luscious Jackson: Citysong]

Alison Stewart: This is All of It. I'm Alison Stewart, live from the WNYC studios in SoHo. Thank you for sharing part of your day with us. I'm really grateful you're here. About the Grammys last night, women's swept the awards. T Swift announced a new album. Jay-Z avenges his wife, Joni Mitchell held court, and one performance warmed even the most cynical hearts.

[MUSIC - Tracy Chapman & Luke Combs: Fast Car]

So I remember when we were driving, driving in your car

Speed so fast, I felt like I was drunk

City lights lay out before us

And your arm felt nice wrapped around my shoulder

And I-I, had a feeling that I belonged

I-I had a feeling I could be someone, be someone, be someone

You got a fast car

Is it fast enough so we can fly away?

We gotta make the decision

Leave tonight, or live and die this way

Alison Stewart: That was Tracy Chapman and Luke Combs, and the crowd went wild. 35 years ago, Tracy Chapman went through Grammy Awards, including Best Female Pop Performance for her song Fast Car. Last year, Nashville-based singer-songwriter, Luke Combs, covered the song and took it to the top of the country charts. There was a lot of cultural commentary about that cover, as you can imagine but there was no hint of cultural divide last night when Chapman and Combs joyfully sang together. Chapman's original version shot to number one on iTunes last night.

The online response ranged from, "Goosebumps to this is what America needed." One internet commenter noted that while last year the conversation around covering Fast Car was often divisive but performing together last night and singing their hearts and souls out, Tracy and Luke demonstrated that music is a powerful force for good. Just thought that was a good way to start the Monday. Speaking of music, next hour we'll have live performances from Josh Ritter and our Get Lit conversation with Pulitzer Prize-winning author Michael Cunningham. That is our plan for today. Let's get this hour started with a conversation about the early days of HIV and AIDS in New York City.

[MUSIC - Luscious Jackson: Frequency]

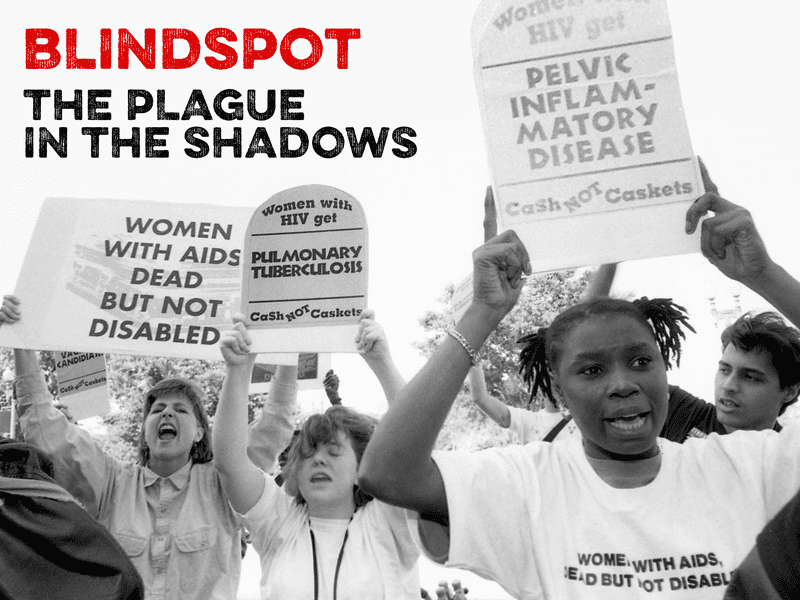

This Wednesday, February 7th is National Black HIV AIDS Awareness Day. In 2021, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention estimated that 1.2 million people aged 13 years and older have the virus. Now, 40 years ago, that information would not have been available, and we learn why in this season of the podcast Blindspot: The Plague in the Shadows. The series takes us back to the early days and how the virus impacted vulnerable communities and is told through personal stories. For example, in the first episode, lead reporter Lizzy Ratner sits down with Lower East Side resident, Valerie Reyes-Jimenez, who recalls how in the '80s people referred to the disease as "The Monster." Let's listen.

Valerie Reyes-Jimenez: People just started disappearing. One day they were there and the next day they were gone. These 20 people that used to hang out in this building, shooting up, they're all gone like Carwash, Bappo, Cocoie, all these people, they're all gone. Where did they go? It was pretty insane. A lot of people died a lot.

Lizzy Ratner: When you say a lot, can you give me how many people off the top of your head do you think you knew at that point who had died?

Valerie Reyes-Jimenez: At least 75 people from the block alone?

Alison Stewart: That's from Blindspot. This season offers insight into the initial conversations about who contracted the virus and how and why that mattered. We hear from experts like Chief Medical Advisor Anthony Fauci, who oversaw HIV research during the time about Harlem Hospital's pediatric ward, and the nurses who treated children with HIV and audio archives of activist Katrina Haslip, who fought for the CDC to include symptoms that affected women in the definition of HIV and AIDS.

Blindspot: The Plague in the Shadows is a collaboration between the History Channel and WNYC. It's hosted by our very own Kai Wright. Joining us today in studio to discuss All of It is Lizzy Ratner. She's the lead reporter from the podcast and also the Nation Magazine's Deputy Print editor. Welcome to the studio, Lizzy.

Lizzy Ratner: Thank you so much.

Alison Stewart: Also, joining us is human rights lawyer and activist, Terry McGovern. She appears in the podcast. She is also a professor and senior associate dean at the CUNY School of Public Health. Terry, welcome.

Terry McGovern: Thank you so much.

Alison Stewart: Also, in studio today, Kia LaBeija, artist and former mother of the Royal House of LaBeija within New York's ballroom scene. She also is featured in the podcast. Kia is The Greene Space Artist in Residence right now-

Kia LaBeija: Hey.

Alison Stewart: -and has a companion piece-- Hey, exhibition of The Greene Space. Nice to meet you.

Kia LaBeija: Hi.

Alison Stewart: Lizzy, the first cases were reported more than 40-something years ago for those of us who were around then, we remember. Obviously, the name of the series is Blindspot. What did you think was missing out from the coverage and the way we think about the coverage of the early HIV/AIDS cases?

Lizzy Ratner: Well, starting in the present moment when people think about HIV and AIDS, they actually rarely think about it these days publicly. When they do, there's this part of the conversation where people say, "Well, it's become an illness that mostly affects communities of color, Black communities, brown communities, men who have sex with men. In fact, it's always been that way. If you go back to the earliest moments of the virus when it appeared. Officially it appeared in 1981, actually, our podcast will get into the fact that it actually started appearing a lot earlier.

From the very beginning, it was a virus that attacked unequally unfairly that attacked Black and Puerto Rican communities, low-income communities, communities of gay men, people basically who were othered, whose society did not want to see. All those many blind spots had horrifying consequences for the way the illness was reckoned with at the time, treated, and the people who continued to be vulnerable to it today.

Alison Stewart: Terry, in '89, you founded the HIV Law Project and served as executive director for about a decade. What do you remember about those initial conversations when you began the project?

Terry McGovern: What I remember is I was a poverty lawyer, so we were seeing a lot of gay men living in the projects, gay men of color, women. What I remember most is how incredibly scared people were, how incredibly sick they were, and how we couldn't actually fix any of the problems that they were encountering. There were huge what we'd now call structural racism and sexism problems.

Alison Stewart: When you think about the kind of questions that were being asked, what were the wrong questions that were being asked?

Terry McGovern: Do you have AIDS? The definition of AIDS was based on studies of primarily white gay men who had access to healthcare. HIV as it attacked the immune systems of people who had terrible healthcare or lived in overcrowded conditions or were women, it looked very different. What we realized is that many people of color and women never got AIDS. They died of HIV disease. The number one question to get a healthcare attendant to qualify for Medicare for everything was, do you have AIDS?

Alison Stewart: Just let that sit for a minute. Let that land. Kia, you were born with HIV virus, grew up having to navigate life in New York City at a time when there was still stigma around it. Would you mind sharing a story from your childhood that stays with you?

Kia LaBeija: A story from my childhood? Well, first of all, I'd like to say that globally, more than half of people living with HIV and AIDS are women and girls. I think that's a fact that I never hear unless you actually look it up, if you do your research, it's not something that is still focused on. Because we're still focusing on the populations of people affected. For example, there's one in two gay Black men is going to contract HIV in their lifetime, which is something that is heavily focused on. Also, over 50% of people living with HIV globally are women and girls. For me, I grew up HIV positive with two parents living with HIV. My mother died of AIDS when I was 14. I had a happy childhood, I think.

I'd like to say that my parents never made me feel scared.

Alison Stewart: That's great.

Kia LaBeija: I always felt like I had a lot of love. Living with that virus, they made it not scary for me. After losing my mom and growing up as a person living with HIV and a young woman living with HIV, it was very, very difficult to navigate. Especially because it was hard for my father and I to deal with it together. A lot of my growing up, I had to do alone and I had to learn a lot of things the hard way, unfortunately, and there's just not-- Or there wasn't at the time a lot of resource information that would've helped me maybe learn things a little bit easier.

Alison Stewart: What questions did you have as a young woman?

Kia LaBeija: I think it's not so much about questions, but it's about experience. I think it's about people guiding you to give you more experience. For example--

Alison Stewart: Meaning you wanted to know someone with a similar experience.

Kia LaBeija: Yes, but also things like, for example, as a young person growing up, sex, the big thing. We, first of all, don't talk enough about communication and sex. If you're a young person living with HIV, and you've never had sex before, and no one tells you like, "Oh, this is how you communicate to another person your status," something like that, for example. I think that's been one of the most difficult things, I think because I had a lot of hard experiences and dealt with a lot of stigma because I didn't know how to communicate.

Alison Stewart: Terry, if you lived in New York City at this time. I can remember being-- At '89, 25. Right in it, and in the thick of it, and if you lived downtown, and you worked in the arts, it wasn't really in the shadows. You knew somebody, you knew somebody who knew somebody, related to somebody who may be had HIV, and who died of AIDS or had AIDS. What was it like nationally? Because I think New York's a little bit different than the rest of the country.

Terry McGovern: Well, interestingly--

Alison Stewart: I think but I don't know.

Terry McGovern: Yes. As we started to see that there was this pattern where we couldn't win cases for women with HIV who were appealing their denial for Social Security Disability Medicaid, because they didn't get AIDS, I began to do a lot of outreach to lawyers around the country. What you found actually was in many cities, it was incarcerated women of color who had put these issues on the map. You often had activists all over the country who experienced the same thing.

Also, the poverty lawyers I reached out to, all were seeing the same pattern. It may not have been as in your face, as in New York, but the pattern was emerging, and in particular, activists in SisterSong and SisterLove in Atlanta. There was a lot going on around the country, but again, for people working with women and children, we were scratching and clawing to just get the issue named. It was a very different context.

Alison Stewart: Lizzy, when you started thinking about putting this together as a reporter and an editor, who did you know you needed to speak to?

Lizzy Ratner: Well, I will say that Terry was one of the first people. Everybody said, "You have to talk to Terry McGovern." I was so glad that I did because Terry was really one of the key people who put me on to the story of women and HIV. It was a story, I'm embarrassed to say that I really didn't know. I guess I assumed that women got HIV, but I didn't understand how significant the numbers of women were, and obviously are as Kia pointed out with HIV. The abject stigma with which they were treated, and the way in which throughout the '80s, and '90s, and even to today, government, doctors, the general public failed to recognize that women got HIV.

It was Terry who really opened my eyes in that regard, and turned us on to a story that is the subject of our third episode, which is the story about a group of women. One woman, in particular, Katrina Haslip, who fought to change the definition of AIDS, so that women symptoms and the symptoms of other people were included in AIDS, but who also fought just generally to get the government doctors to recognize that women were struggling mightily with this epidemic.

That the very women who were doing that, were women in prison, as Terry said, women who, in our podcast define themselves as the people who've been left out the marginalized, of the marginalized, the people that society actively forgotten, said, "Forget it, we don't want to deal with you." It was really, in this one prison, in particular, in Bedford in upstate New York, that a really extraordinary group of women, forged, I think, what is maybe the first group for people with AIDS for women with AIDS in the country. Then of course, outside of that, there was this remarkable movement. Terry was definitely one of the first people I had to speak to.

There were others, and I could list them all. Everybody was generous and amazing, but I want to let you also ask questions to other people.

Alison Stewart: It's something it gets to in episode 3 is sexism in medicine. It's very, very clear.

Lizzy Ratner: Deep.

Alison Stewart: It's deep and clear.

Lizzy Ratner: It's profound.

Alison Stewart: Would you give just one example of how it pertains to women who have HIV?

Lizzy Ratner: Sure. I think at the beginning of the story, let me just say this was starting in the '80s. The idea of women's health was novel, and it was not popular. The template for all health was the male body or the body-gendered male. We have this one doctor, Cathie Anastas who was a medical student late '70s and '80s and describes being taught female anatomy on what was basically a pin-up. We were all pretty shocked when we heard that. There's also the fact that until the '90s, if you could get pregnant if you are what people now sometimes term pre-pregnant, you are pretty much not included in most clinical trials, you could not be part of clinical trials.

All clinical trials were being performed on male bodies. Obviously, that's a problem. That's one of many, many problems. The one more thing I will say, and then I will stop is that I think the issue is also not just the sexism, which was deep and profound, and across the board, but the particular women who were getting sick. I think we cannot leave that out that the majority of women who were getting HIV were women of color. Many were low-income. Some got it through injection drugs, some got it from partners who used injection drugs. I think, frankly, the racism and classism and general bias and bigotry of that era really affected these women, in particular.

Alison Stewart: We are discussing Blindspot: Plague in the Shadows. The first three episodes are out now a new one drops every Thursday. I'm speaking with Lizzy Ratner, Terry McGovern, and Kia LaBeija. We'll have more after a quick break. This is All Of It.

[MUSIC - ]

Alison Stewart: This is All Of It on WNYC. I'm Alison Stewart. We're discussing the podcast Blindspot: Plague in the Shadows. The first three episodes are out now a new one drops every Thursday. My guests are reporter, Lizzy Ratner, activist and lawyer, Terry McGovern, and Kia LaBeija, Artist in Residence at The Greene Space I might add. Terry, when you think about the activists at this time, tell us a little bit about what worked.

Terry McGovern: I think what was pretty amazing is just as a lawyer seeing all of these people actually dying before I could get them Medicaid or figure out what to do about their children. All of the issues that women were facing hadn't been thought out. On the other hand, you had this vibrant act up, which was using all of this creative, direct action. I, for example, went to act up because I didn't know what to do, because I was seeing all these clients who had HIV and there was this incredible group of activists who was talking about the AIDS definition and all of these issues, and they were actually willing to work with us to organize HIV positive women.

The leadership in changing all of this came from HIV-positive women of color, incarcerated first, but really, and everybody was like, "These women aren't going to want to talk to the media, et cetera." Not true at all. Actually, we had to hold sessions where we explained, "What is happening to you is not because you did anything, it's because of discrimination. They didn't study women, they didn't warn you that you could be at risk, you had no idea that your child was going to end up HIV positive." In a sense, we were able to explain the policy landscape and see this transformative effect on women who felt really terrible.

I've never seen anything worse than women finding out that they were positive, through their child testing positive when they had no idea. Nobody offered them a test. Nobody told them they were at risk. The investment of explaining exactly why they were being discriminated against and how really paid off and you saw women step into their own power, and really lead on this. Some of the most effective activism was really HIV-positive women, talking to the media, protesting outside of Health and Human Services. Actually, every litigation step we took was accompanied by really creative activism that centered HIV-positive women, and that worked a lot.

Alison Stewart: Kia, what was the role of activism in your life?

Kia LaBeija: My mom was heavily involved. My mother also found out she was HIV positive, not until 1993, which is three years after I was born. She got very, very sick. She got a cold that wouldn't go away. She went in, they did all these different tests. They're like, "Oh, let's just test you for HIV." My mother who is a mixed race, Asian woman, heterosexual woman, they're like, "Oh, you probably don't, but let's just try. Let's check it out." The test came back positive, my dad's came back positive, and mine came back positive. Sorry, what was your question? I just got lost in my own story.

Alison Stewart: No, thank you for sharing your own story. I was asking about the role of activism in your life.

Kia LaBeija: Right. My mother joined APICHA, which at the time was Asian Pacific Islanders Coalition against HIV and AIDS. She was a board member. She was also on the Pediatric Committee of ACT UP, and she brought me everywhere with her. I went to all different types of conferences. I did meet other children. She was also part of a group called Just Kids, which was a group for families, basically, parents who were living with HIV that had children living with HIV who are trying to figure out, what do we do if I die? What do we do if both parents die? What do we do with our children? What do we do if our children die? They're just trying to figure out everything.

Just watching that as a young person was very influential to me and so I've continued on with my activism through my art.

Alison Stewart: Lizzy, we get to meet some of the healthcare workers specifically at Harlem Hospital in the pediatric ward. Some of the stories, it's interesting, and I can imagine this was a balance when you put them together because some of the stories are really heartbreaking. Some of them are a little bit funny. The little kid who's a terror on the floor. That story is terrific.

Lizzy Ratner: Shivon. Yes.

Alison Stewart: I don't want to give too much away for folks who are going to listen to the podcast, but I want to play a clip from Maxine Frere. Tell us about Maxine Frere. Give us a little setup and then we can hear from her.

Lizzy Ratner: Maxine is one of the truly remarkable people we met. We met incredible people. She was one of them. She spent 40 years as a nurse at Harlem Hospital. She was born and raised in Harlem, grew up in the shadow of the hospital, knew her whole life that she wanted to be a nurse because doctors fixed bodies, nurses help your soul. When other people on staff at Harlem Hospital were afraid to work with people with AIDS, Maxine volunteered. She stepped right up. She said, "I need to do this for my community." She ran clinical trials for children with AIDS. Then was just, I think, the head pediatric nurse dealing with HIV and AIDS and a truly incredible human being.

Alison Stewart: This is a clip from Blindspot: Plague in the Shadows. Maxine Frere pediatric nurse at Harlem Hospital who talked about what it was like to treat children with the virus.

Maxine Frere: The death was hard. It was hard on all of us. I think the preparation helped us get through a lot of it, be able to talk about it amongst ourselves because we needed to have a little counseling, sometime ourselves crying all the time was very difficult. They trusted us. They trusted us emphatically, I think most of them. I remember one little boy said, "If I didn't have HIV, I wouldn't have met you guys." He said, "I wouldn't have met you."

Alison Stewart: What kind of support did these hospitals have?

Lizzy Ratner: Well, that's what's actually remarkable. They had very little support. Harlem Hospital is a public hospital. Public hospitals have always been underfunded but in the 1980s, it was an era of austerity. After the fiscal crisis, the city yanked a lot of funding from frankly, all public resources. There's a story in our episode where the head of the whole pediatric ward talks about not having Robitussin. They didn't have sheets a lot of the time. It was really bleak.

You had many, many children with HIV who are arriving on the ward. We explained why and how that happened, but out of what was really an economy of abject scarcity, people like Maxine and her remarkable colleagues, they just made do. Sometimes, on the material front, they would literally go to the private hospital next door and steal Robitussin and things like that. They were just hustling to get what they needed, and they did, and all power to them for that. Really what they supplied was, this is going to sound cheesy, but remarkable love and courage.

In the face of a system-wide social collapse, when I say social collapse, I don't mean within the community. I mean really by the city not showing up, you had people who showed up on a very personal level to try to provide family support care treatment in the face of an illness where there was very little of all of that.

Alison Stewart: Terry, what would you consider your greatest victory in terms of advocacy?

Terry McGovern: It's such a hard question because as my friends here were both saying, really '93, the treatment breakthrough happened in '95 so really people were dying in huge numbers. Right at the time, we actually won the Class Action Against Social Security about the use of the AIDS definition for being discriminatory was the precise moment where Katrina Haslip died, where all of the clients were dying. At the moment where the activists, the litigation, all of it led to these final policy wins, it didn't feel like a win at all because all of the people we had fought side by side with were dead or dying.

When we did win that whole major expanded definition get the Social Security criteria changed, the numbers of women and particularly women of color went up over 40%. All of this activism did change the perception and did put women and girls on notice of the risk and the possibilities and all of it. It's hard to use the word victory in any of this, frankly.

Alison Stewart: Maybe change. The biggest change. An important change is a better word.

Terry McGovern: Yes.

Alison Stewart: Thank you for saying that.

Terry McGovern: Sure.

Alison Stewart: Kia, tell us about what's going on downstairs in The Greene Space.

Kia LaBeija: Oh my God, I'm still just in that Maxine episode.

Alison Stewart: I know.

Kia LaBeija: All the episodes really shook me. I got to hear some of the drafts. Oops. I don't know if I'm supposed to say that. I got to hear some drafts.

Alison Stewart: [crosstalk] Totally fine.

Kia LaBeija: They shook me so hard. I sat with that Maxine episode so hard. I think mostly because I'm so much also a part of that history and to learn about that history now at 33, I think really shook me. That's why I'm here at The Greene Space continuing to help educate people through art. Right now, I have images that are up of different subjects from Plague in the Shadows, including Terry, including Maxine.

Tonight we have an amazing docu-theatre performance, which is looking at the CDC hearings. You'll hear some of those voices of women that were really very vocal and very enraged, which is beautiful and powerful. On Valentine's Day, I am hosting the first LOVE POSITIVE WOMEN Valentine's Day Dance here at WNYC. No, here at The Greene Space. It's going to be really beautiful with curated music by DJ Isas Lobas. We are celebrating women living with HIV. Then on the February 23rd, I'm actually going to be having a listening party/live musical performance of a project that I'm working on with my father, Warren Benbow, and my brother Kenn Michael, two amazing veteran musicians.

Alison Stewart: The name of the podcast is Blindspot: Plague In the Shadows. My guest has been Kia LaBeija. Go check out all the art and the dancing and the music and all that good stuff in The Greene Space, as well as Terry McGovern. Terry, thank you so much for your time, as Lizzy Ratner reporter on this series. Thanks for coming in.

Lizzy Ratner: Thank you so much.

Kia Labeija: Thank you for having us. Thank you.

Terry McGovern: Thank you very much.

Copyright © 2024 New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.

New York Public Radio transcripts are created on a rush deadline, often by contractors. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of New York Public Radio’s programming is the audio record.