Barbara Butcher on Death (and Life) in 'What the Dead Know'

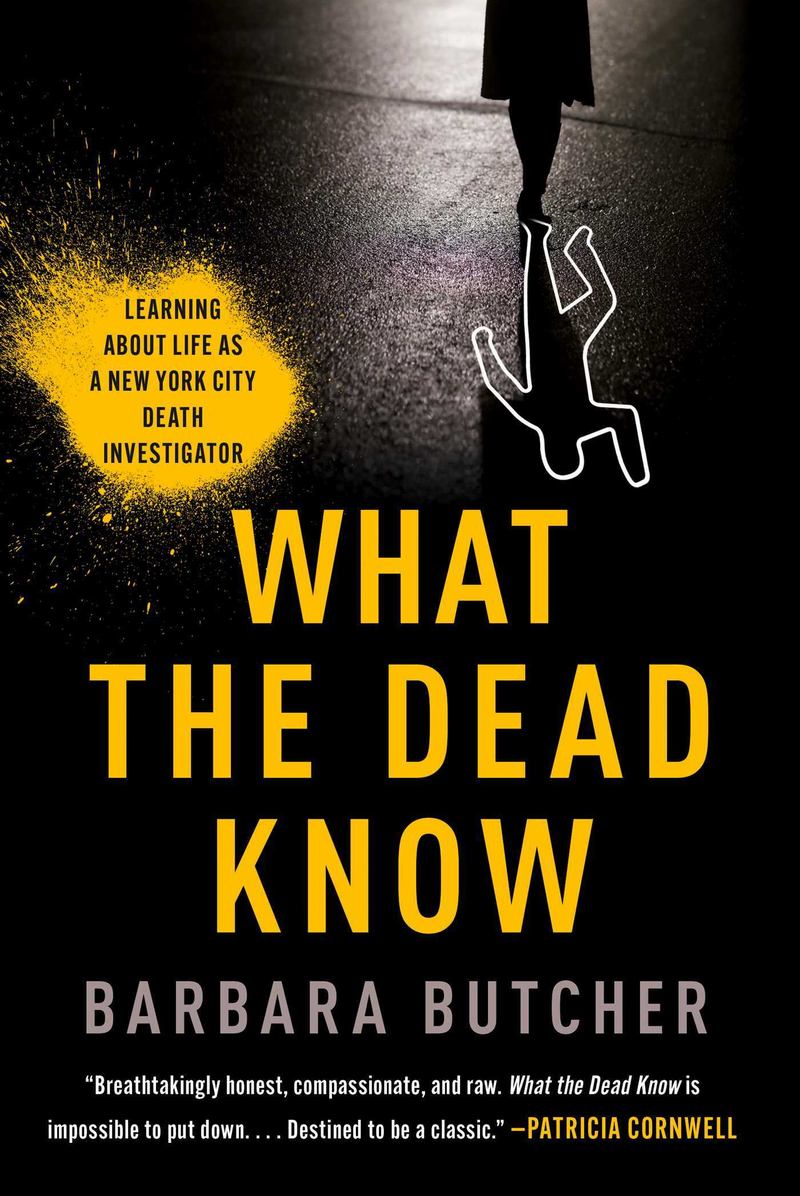

( Courtesy of Simon and Schuster )

[music]

Alison Stewart: This is All Of It on WNYC. I'm Alison Stewart. Barbara Butcher has looked death straight in the eye, so to speak. It was a big part of her job as the death investigator at New York City's Office of the Chief Medical Examiner. She inspected thousands of death scenes throughout her career, 5,500 by her count. Her new memoir, What the Dead Know takes readers through the hard and sometimes gory work of figuring out if someone was killed, died by suicide, or was the victim of an unfortunate accident. She helped solve some of New York's most gruesome homicides and was involved in the 911 victim identification process.

She's candid about a misstep at that time as she is about her history with alcohol addiction, and shares the mental and emotional toll it took to deal with the dead for a living. Kirkus Reviews called Barbara's memoir "heartbreakingly beautiful, and a gritty humorous portrait of her life." With me now to discuss her new memoir, What the Dead Know, is Barbara Butcher. Hi, Barbara.

Barbara Butcher: Hi, Alison. Thank you so much for having me on.

Alison Stewart: Before we begin, we want to let listeners know this conversation may include some detail about death and crime as well as suicidal ideation. If this conversation is triggering at all, the suicide and crisis lifeline number is 988. With all the police procedurals, which we all watch CSI, Law & Order they are popular, they are fictional. What does your job really entail?

Barbara Butcher: Well, for one thing, the forensic pathologist does not go out to the scene, especially in high heels and a dress, and does not start rolling the body around or poking their fingers into bullet holes. In fact, forensic pathologists rarely go to scenes at all. Their job is to do an autopsy, and an autopsy gives you a cause of death, like a gunshot wound, cancer, heart attack, but someone needs to provide a context for that death to determine if it's a homicide, suicide, accident or natural, and that person was me.

As a death investigator, I go to the scene of any death and work with the police and examine the body, examine the scene, talk to witnesses. Then just investigate it to provide that context, write a report, take the photographs, and now hand them to the forensic pathologist who can do the autopsy in full knowledge of how this death occurred.

Alison Stewart: You wrote about your first encounter with your future boss, Dr. Charles Hirsch, and he said that you aren't actually working for the dead. You are working ''for the families of the dead, and that's harder.'' What was the moment when you knew this was true?

Barbara Butcher: Yes. I think the first time that it hit me literally like a face punch or a punch to the heart, quite frankly, was I went to the scene of a suicide, a young man who had gone out the 24th storey window, and his mother was there. Now, he was a young gay man, and he had so much fun together. She'd come visiting from Virginia, and they'd spend the weekend going to restaurants and plays and shows and gossiping and having a ball. On this particular weekend, he said, "Please come, Mom, I'm waiting for my HIV test, I'd like you to be with me."

They had a ball, and then he was sitting on the bed at two o'clock in the morning drinking wine, and then he said, "Excuse me for a moment", and he never came back. She looked all over the apartment and couldn't find him. Just an open window. She called the police. They came, I arrived, and it was evident that he had jumped out the window. We found him in the alleyway behind the building. She was staring at me, and she turned and started banging her head against the wall as hard as she could. I grabbed her by the shoulders, and said, "What are you doing?"

She said, "You're just a bad dream. You're a nightmare. I'm trying to wake up." I could feel her pain. It was so overwhelming. Not only to have a child commit suicide, which is hideous, it's unbearable, but to have so much fun, and to not understand, why would he just go out the window? I could never figure that out either could she obviously. I knew then that I was not there for him. He was long gone. It was all about her and her pain and trying to find some way to give her comfort. I held her for a moment, I mean, we're not really supposed to do that. We're supposed to be distant and detached, but my God, my heart was breaking for her.

Alison Stewart: My guest is Barbara Butcher, the name of her memoir is What the Dead Know. She's a former death investigator here in New York City. Part of your job is not to immediately make a decision about what's happened here. I know what's happened here, you're an investigator. How do you look for the truth? What are some of the things that you employed when you were an investigator to make sure that you stayed neutral and looked for the truth?

Barbara Butcher: The first thing is the notification. The police would call our dispatch unit, and say, "We've got a homicide in the 24 Precinct, and I'd always say, "No, we don't, not until I say we do." [chuckles]

Alison Stwart: There's a death in the Precinct.

Barbara Butcher: Yes, it's a death. That's all we know. If you want to say it appears suspicious, that's great. I don't want to ever walk into a scene with a preconceived notion because it's happened. I've gone to what was quite obviously a homicide, he had a gunshot and a hole right in the middle of his head, and there were shell casings on the floor. However, when I came in closer and looked at that bullet hole, I saw that it didn't have the abrasion at the ring where it entered, which is quite typical of a gunshot wound. Then I noticed that he was at the bottom of a stairway and he stunk of alcohol, really wreaked of it.

At the wall, at the foot of the stairway, the walls came to a corner and they had that stone molding cornice worked on them, it was quite pointy. When I looked closely at that I saw there was a little bit of blood, a little bit of flesh. Then I realized, "Wow, he fell down the stairs, hit his head on that wall and cracked his skull, and died." The police said, "Wait a minute, Barbara, come on, the shell casing is 22 is all over this floor?" "Well, let's explore it." It was a tenement where the open door goes and the long hallway goes out to an alleyway in the back.

When we went out to that alleyway, we saw a target on the fence, and what it turned out to be was kids were using that hallway as a shooting gallery to literally do target shooting with a 22 pistol out the back door. Those shell casings had nothing to do with the death. They were a red herring. Police, of course, were very happy to hear that it was not a homicide, that's a lot less work to have an accidental death. Just not having a preconceived notion. Secondly, someone once told me, "Take your hands off your mouth and put them over your ears."

Stop talking, start listening. That was a powerful lesson. You've got to listen to the witnesses. You've got to listen to the families. Because they'll tell you everything you need to know.

Alison Stewart: Have you ever been squeamish?

Barbara Butcher: In my whole life, no. Now I'm a little squeamish. Well, now I'm a little squeamish, that's an understatement. Okay, now I'm a paranoid, panicky, PTSD-ridden lunatic [chuckles] but no, I was never squeamish as far as seeing blood or gore, any of those things, never.

Alison Stewart: You write about it, very-- Graphics' the wrong word because makes it sound like it's gratuitous, but you were very descriptive in the book. What were your conversations with your editor like about describing wounds and bullet holes and decapitations, et cetera?

Barbara Butcher: Actually, my writing teacher is the one that said to me, instead of just saying there was a huge slashing wound to his neck, he was decapitated. She said, "Give us something a little bit more comparative, something that's a little unusual that can take the reader there without making them disgusted." In a particular case of two men with their throat slashed, I wrote that one of them his neck was like the mouth of a screaming puppet the way it was opened and red. To describe the smell of a decomposed body, which is beyond description, really, but I noted to me that it smelled like a strawberry milkshake made with garlic and say no more. There you are. That's a disgusting smell. [chuckles] I tried to be a little bit more-- Perhaps it's idiosyncratic, but it's a little more using everyday objects to describe something horrifying.

Alison Stewart: My guest is Barbara Butcher, the name of her memoir is What the Dead Know. She's a former death investigator here in New York City. You start the book with the scene where you encounter a dead person and you come to realize that this person had actually booby-trapped their body so that whoever discovered it or touched it would also be killed.

Barbara Butcher: Yes.

Alison Stewart: First of all, what did you think when you realized that? It seemed like it was one of those ''aha'' moments.

Barbara Butcher: Yes. Shall I tell the story [unintelligible 00:11:00]

Alison Stewart: Sure. You can tell the story.

Barbara Butcher: I had my left hand in a cast. I had cut a tendon doing some woodworking, which I'm not very good at. I was carrying on and moaning and complaining about having to work, but I was at a sick time. That night I had a call for a man found hanging in his apartment. When I got there, the apartment was pitch black and the cop said, "Oh, there's no electricity. Con Ed must have turned it off, and there's a guy hanging in there, looks like a suicide."

''Okay, great.'' I had a weak flashlight and I went in there and did my examination. At the time we used Polaroid cameras. This is back in '92, and with their bright flash, I took lots of pictures. I examined him as best I could, looked at the scene, and clearly, it seemed like a suicide. Then I went to do what I normally do, which is to cut him down. I'd stand on a little step stool and with my left hand, grab the ligature, and then with my right cut through the ligature, and that way he could come down easily to the floor, not crash to the floor.

Then I realized I can't do this, my hand's in a cast, and I didn't want to ask the cop because of the union rules. I figured, when the mortuary techs get here, they can do it. I'll just call the office and ask them to do it neatly and let him down nice. Then I went back to the office. I was writing my report and I was looking at the photographs at the Polaroids, and I saw that around his neck, hidden beneath the thick folds of his neck was an orange outdoor extension cord. ''Oh, that's good. That's nice and strong.'' Then in the next photo, I saw that that extension cord was plugged into the socket.

I was like, ''Wait a second. There's no electricity. Why is he plugged in?" Then suddenly it came to me like a Sherlock Holmes clue. It's a strange moment of, "Oh my God." I called the apartment and I said to the cop, "Go try to screw in the light bulbs in the lamps." He said, "What for?" I said, "Just do it quick. Don't touch the body." He screwed the bulbs in, and sure enough, the lights came on. There was electricity, but this guy had set it up so that it would appear as if there was no electricity in the house. He planned this whole thing, and then he booby-trapped himself. If I had cut through that cord, I would've been electrocuted, maybe even killed.

Why would a person do a thing like that? I'm like, "Wait a second. If you're going to kill yourself, okay, I'm sorry, but why take someone else with you?" We see that over and over in these mass shootings. I deem it an angry suicide. Maybe they're angry because no one paid attention to their pain and sorrow, and they're just so angry that they're going to take others with them. Or maybe people want to be remembered for something and this guy will sure be remembered because he's in my book. [chuckles]

Alison Stewart: What have you learned about human nature from this job?

Barbara Butcher: Oh, gosh. In the first probably five years, I had seen so many homicides, so many rapes, so many strangulations, so many children who died, and the constant repetition, the constant exposure made me feel that people were evil, period. That the world was an evil, horrible, cruel place, and that everyone walking down the street was either a potential victim or a potential murderer. That kind of exposure just washed through me, and it made me sad. Really sad. It was a long time before I realized that analytically speaking, you can look at the statistics.

Most people are good. The world is a good place. The world is a beautiful place. Now, I had been warned about that when I was in my training, but I forgot the lesson. That was, I was watching a forensic pathologist do an autopsy on an eight-year-old girl who had been strangled and raped, and smothered, and I was horror-stricken. I was so upset. Identifying with this little girl, I couldn't bear it. I asked the pathologist, how do you go home at night? How do you live day to day with the knowledge of what you've just seen?

She said, "Barbara when you leave this place, surround yourself with things of beauty, art, love, food, music, dance, everything. Just let creativity absorb you and wrap you up, and don't skip a day because this will get you." She was right. It was years later that I realized I had to do something creative, something wonderful to wash away the sorrow.

Alison Stewart: There was a time in your life you couldn't have imagined being able to do that, to be able to spend your evening wrapped in opera or in jazz, or in a good book because you were extremely candid in the book about you had debilitating alcoholism. Fall down on the street and break your teeth alcoholism. Friends not wanting to help you anymore alcoholism. What was the moment when you realized, "I may not survive this alcohol addiction unless I do something?"

Barbara Butcher: I think it was the night that I-- Oh, I went to a Chinese restaurant up on the Upper West Side where they gave away free wine with dinner. My girlfriend and I would split an entree and each get an appetizer, and then we'd sit there for three and a half hours drinking the kerosene-flavored wine, and the waiters hated us, of course, and there was a line of people outside who hated us waiting for our table. I drank and drank and drank, and then we met other friends for drinks later. Then I gave all of my money away, everything in my pocket to a man in the street who said, "Can you spare a dollar?"

I gave him, I think $80, and I said, "You really want it for drugs, right?" He said, "Yes." I said, "All right. I applaud your honesty." Now, I don't remember any of this. This is what my friends told me. I was in a blackout. Just going home, I stumbled and fell. I fell up the stairs, which is difficult to do unless you're really drunk, and I woke up the next morning in a tangled mess of sweaty sheets on the floor with the most over overwhelming sickness of my life. I was anxious, I was terrified because I knew that I had lost a piece of my mind.

I couldn't remember what my friend was telling me, and I was terrified, really, really scared. I went to an AA meeting that day, and then another one that night, and within a few days when I didn't drink, I suddenly felt normal. I actually felt good. I had been poisoning myself every day with cheap wine, 5.99, the half gallon. Really terrible stuff. That alcoholism was unfortunate. I ruined a lot of things in my life because of that. Getting sober, now there was a gift. A universal, oh, just fantastic gift that showed me a whole new way of life.

Alison Stewart: What was it like for you working in such an intense environment, knowing that one of your, although it may not have been the positive coping mechanism, that you had used alcohol in the past?

Barbara Butcher: There was one scene I remember very clearly a young girl, a victim of a serial killer up in East Harlem. It was gruesome, just terribly gruesome. We were up on the roof. She died up at the top of the stairwell, and I was standing up on the roof, getting some air, trying to clear my mind from this horror, and the cops were out there and they said, "Barbara, we're going to go out for a drink after this. We all need it. Why don't you come with us?" I wanted to so badly. I wanted to be with the guys. I wanted to drink. I wanted to laugh.

I knew we wouldn't talk about this case. We talk about police gossip, what the commissioner screwed up today, or who's a bad guy or who's a good guy but that's what I wanted. I knew that if I went into that bar, that would be the end of it. I would have a drink and I would not be able to stop. There was nothing to be gained from that so instead I stood at the edge of the roof and I prayed. I just looked up at the sky and said, "Please God, take her, this young girl home, take her back to you." I'm not a religious person or anything, but it's the only thing I could think of to do was to send her home wherever that was.

Alison Stewart: Do you bring your emotions to the job? Did you bring your emotions to the job or did you have to keep Barbara separate from the medical investigator?

Barbara Butcher: The only way to do the job, and this goes for first responders, for last responders like me and so many others is to detach in the moment. In that moment, at a crime scene or at any death, at first, I'm struck with horror, grief, sadness, terror. All these emotions come washing over me but I immediately close them down and instead, I become an analytical machine. I think of the forensics. I think of the cause of death, the medical aspects of what I'm seeing and hearing, and then when I've gotten all that done, ostensibly I can turn my emotions back on but guess what?

It doesn't work so well at all. Once you detach, especially if you try to turn off one or two emotions, they all go. You can't go and feel love when you've turned off everything else. My relationships were not going well, especially after 911. That just killed my marriage at the time. It's not possible to completely detach and then completely come back to people. It just doesn't work so I did my best.

Alison Stewart: That's an important lesson. The name of the book is What the Dead Know: Learning about Life as a New York City Death Investigator. It is by Barbara Butcher. Barbara, thank you for being with us.

Barbara Butcher: Thank you. It's a pleasure, Allison. Please stay safe out there.

Alison Stewart: That is all of it for this week. All of it is produced by Andrea Duncan-Mao, Kate Hinds, Jordan Lauf, Simon Close, Zach Gottehrer-Cohen, L. Malik Anderson, and Luke Green. Our intern is Aki Camargo and Meg Ryan is the head of live radio. Our engineers are Juliana Fonda and Jason Isaac. I'm Alison Stewart. I'll meet you back here next time.

Copyright © 2023 New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.

New York Public Radio transcripts are created on a rush deadline, often by contractors. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of New York Public Radio’s programming is the audio record.