Artist Michael Ray Charles' Rare U.S Exhibition

( Courtesy Templon, Paris — Brussels — New York / Hedwig Van Impe © Remei Giralt )

[music]

Alison Stewart: This is All Of It from WNYC. I'm Alison Stewart. Calendar alert, this is the last weekend to check out artist Michael Ray Charles' first solo show in New York City in more than 20 years. Throughout the 1990s and into the early 2000s, Charles created works that were audacious and subversive takes on racism. He marries minstrelsy with iconography to get at the origins and the power these images possess to perpetuate bigotry. For example, in his Forever Free series, he has a piece called American Gothic. In place of stoic white man, it shows a cartoonish mammy-esque woman not holding a pitchfork but a broom. Next to her is a Topsy meets Al Jolson-like figure looking surprised.

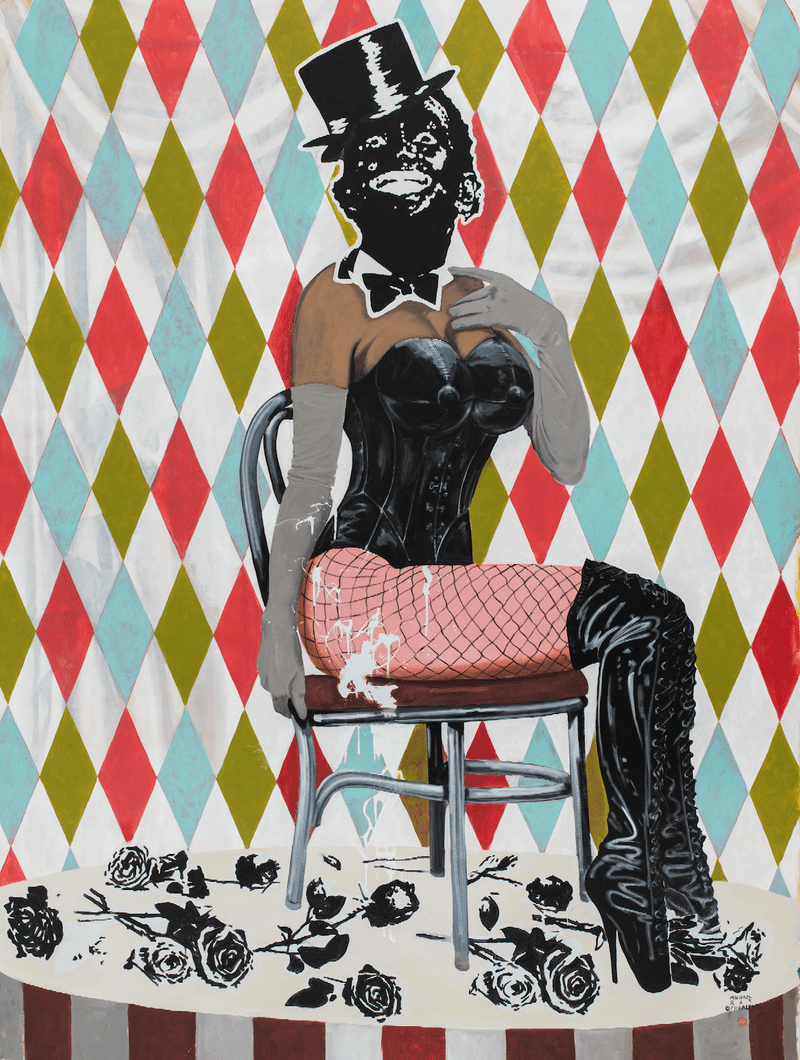

His current show at Templon Gallery features a series of images, bodies, and finery, Elizabethan collars, corsets, and evening wear but the edge is clearly there, with masculine and feminine features sharing the same body. Titled VENI VIDI, the show features pieces dated this year and as far back as 1993. Spread over two levels, we see how his visual language has evolved, especially around gender presentation while remaining focused on tropes.

The show will close on Saturday, May 6th, so you've got a couple of days to still check it out. Hopefully, this conversation with Michael Ray Charles will inspire you to do so. It was a winner. He joined me back in March when the show first opened. I began by asking him why he decided now was the right time for his first New York show in two decades.

Michael Ray Charles: Why was this the right time? I'm not sure how to answer that. It just seems like it was a natural progression. It was long overdue, and I think the world has changed a lot since I've decided to remove myself from exhibiting. I think we've obviously with COVID a reorg of sorts, and the rise of technological advancements, the internet, and our dependency on it. Then there's a generational shift. There is all these things are happening, and I felt that this was a better time than ever, and plus I'm an empty nester now.

Alison Stewart: [laughs] Oh, your birds have flown the coop.

Michael Ray Charles: Yes.

Alison Stewart: [laughs] What does that feel like for you?

Michael Ray Charles: A little strange at first. I'm more like a Cosby dad. At first, I wanted them gone, and now I miss not having them around.

Alison Stewart: Now I'm going to take a personal turn. Do you find your work habits, your practice is different now that you're an empty nester?

Michael Ray Charles: No.

Alison Stewart: No.

Michael Ray Charles: No, not really. I still a night owl, and once I hit a certain time, it's well, six o'clock is not that far away. I think I could stay up till six in the morning, and then there's the day that starts.

Alison Stewart: Wow. You work all night?

Michael Ray Charles: Yes, sometimes all night.

Alison Stewart: What do you like about the night?

Michael Ray Charles: The quietness. It's a different sound, and sometimes I like to think that I'm the only one up working, but I am more engaged, and there's a different sound. The ambience of the noise of the day is different. It's just a peacefulness.

Alison Stewart: That's interesting because when you first came in here, you noticed how quiet it was in the studio.

Michael Ray Charles: Yes. It allows me to have more of a conversation with myself. I think we store a lot of information as we go through our daily experiences, and this dead quietness allows me to be more introverted and be able to pick and pull from the trays of categories of subject matter, and thoughts and sounds.

Alison Stewart: You said your language is very interesting when you described the past decade and a half, you said you removed yourself from the exhibition. Why removed? Why is that the right verb?

Michael Ray Charles: You're a good listener, by the way. [chuckles] I've always felt and still do, I teach to make a living, and live to make the art that I want to make, and that hasn't changed. I started making work that piqued my interest and the complexities of what I had embarked upon far outreached the expectations of having a show every year, and the show here and there. I noticed some changes happening with the rise of the internet, the dependency upon it. I wanted to dig deeper into my work, and I had some opportunities to spend a lot of time abroad, and I took those opportunities so that I could understand the impact of minstrelsy in various countries that I visited, and try to discover what's the connection, how do they intersect with what started here in America.

Alison Stewart: My guest is Michael Ray Charles. The show is called VENI VIDI at Templon Gallery through May 6th, by the way. The piece that the exhibition is named after is, I'm going to try to describe it. It's an androgynous black bust hovering above the table, and in the bust's hands, a red string, and dangling on one of the string is a face of Abraham Lincoln, and on the other is Lyndon Johnson. I imagined Lady Justice holding the scales kind of imagery. What prompted this painting, considering it as from last year?

Michael Ray Charles: I think a lot of issues that ideas arrive from and around COVID and the isolation, levels of uncertainty, the adjustments that we've had to make as communities both near and far, and just issues and ideas about Black identity, and, of course, a lot of not references, but issues with identity and race, and going back to George Floyd's death and the team Black versus team white whole thing. We're talking about the Civil War again, and for me, I think I tried to make a painting. Really it was my wife's idea, one of her ideas. I tried to make a painting that attempts to represent, or at least capture that as a moment where I positioned an androgynous figure dangling between two presidential and political brackets. The emancipation and civil rights. I think a lot about who Black people are today has to do with those particular brackets in a sense.

Alison Stewart: It's always amazing to me that 100 years, 1860s and 1960s, and how active both of those decades were, and how it activated all kinds of people to do all kinds of things. I think it's interesting when I was looking at the painting that, I'm trying to figure out where this bust is, because it's in a place. It's either because of the floor, and you can tell by the wall behind it has certain textures, and it almost looks like a halo around the bust's head. Where is it? Is it meant to be a museum? Is it meant to be at home?

Michael Ray Charles: It's more so to bring about the presence of an interior space, and one that harkens back to wall decorations from a certain period, architectural history of 1600s. You can see that also woven through in patterns that I've selected in the backgrounds of other paintings.

Alison Stewart: Yes. There's a lot of Harlequin, and the collars, the Elizabethan collars.

Michael Ray Charles: Commedia dell'arte, yes.

Alison Stewart: The title, of course, comes from veni, vidi, vici. I came, I saw, I conquered, attributed to Julius Caesar. The gallery opened on the Ides of March when Caesar was killed, coincidence.

[laughter]

Michael Ray Charles: I was interested in wordplay. I spent some time in Rome a few years back. I came, I saw, and it was part that I wanted to use. I felt like I could at least re-enter with some kind of presence I guess re-enter New York. It's good to be back. It's a beautiful city. It's not the same it was in the '90s. Of course, things change, but it feels great to be back. It was a great crowd. I enjoyed it.

Alison Stewart: Talking about cities that change, you live in Austin.

Michael Ray Charles: I live in Austin, yes.

Alison Stewart: Talk about a city that's changed since the '90s.

Michael Ray Charles: Almost night and day.

Alison Stewart: Truly. They used to joke about the dillionaires came in, and changed it, but it's even beyond that at this point.

Michael Ray Charles: I remember when the dillionaires decided that they were dillionaires, and an acre of land overlooking the lake went from $10,000 in one year to $40,000 if not more. Then the Lamborghinis and all those kinds that are called Bentleys and Walmart parking lots. Then I moved away for eight years and recently moved back, and drastic change in eight years.

Alison Stewart: What's that? I haven't been in a long time.

Michael Ray Charles: Oh, wow. It's a city in all the ways that cities are cities today. Of course, we have issues with homelessness, a great significant presence of that that didn't really exist in the way that it does today. Gentrification and white flight-

Alison Stewart: Oh, interesting.

Michael Ray Charles: -displacement of minority communities that had been in place. I said displacement, but taxes are crazy. Every home is $1 million. California has moved in.

Alison Stewart: I can remember being there maybe 10 years ago, and I was in a bar and this old time was next to me. He said, "Some lady came about in my house and said she wanted to sell it because it was in Travis Heights. What the heck is the Travis Heights?"

[laughter]

It's a real estate designation, and he didn't want to sell his house. He wanted to stay, and I think about that gentleman, sometimes.

Michael Ray Charles: There's been a lot of that. It's been amazing to see. Austin, in my opinion, has been a really wonderful place to live. Now the world has come in a different way. We talk the live music capital and all the ways that it's marketed. I listen to a lot of live music there. Now the tech companies, everybody's here, Google, Tesla, you name it, and it's interesting to see.

Alison Stewart: Is it a place where an artist can still live?

Michael Ray Charles: Absolutely.

Alison Stewart: My guest is Michael Ray Charles. The name of the show is VENI VIDI at the Templon Galerie through May 6th. I'm reading the press material, and it highlights the language of Dandyism as a theme. I thought it was interesting because you see it in many pieces in the show masculine and feminine images intertwined. There's one particular I want to describe, it's got L. Johnson's face in Black faces, the head, a male torso, and Elizabethan collar, one arm is white, one arm is Black.

They both have evening gloves. Then there's a skirt with a slit and a woman's leg and a high heel, the way Angelina Jolie posed that one time on the red carpet. What did you want to explore about gender? What have you been thinking about gender? How has it worked its way into your work?

Michael Ray Charles: For some time, my go-to reference has always been a reference to male figures. I'm not quite sure where or why that more or less is the case or has been the case. A few years back, I came up with an image that I felt could at least speak to both male and female. I was excited about that and wanted to continue that moving forward because I didn't want to continue to leave out a reference to women or to reference women in a certain way in work.

In light of the rise and presence of LBGTQ community and issues from fronting this particular community, I felt that I wanted to make work that alluded to or suggested the presence of this dynamic in the way that it exists I think today.

Alison Stewart: One other image in there that just I sat with for a while and it made me smile. I'm not [unintelligible 00:14:59] it was supposed to but it did. It's a figure that's looking like it's doing a curtsy and we see a red curtain pull to the side and it's a muscular male torso, a white hand. The legs are holding a skirt, which looked to be like a kente cloth in black and white.

Then you look down at the feet and I'm like, "I recognize the feet," and then it took me a minute. It's Dorothy's red slippers on the Yellow Brick Road. What is the intended effect when you leave an image that's so adored? You've done this with Norman Rockwell before, that is just so part of America into a painting which is interesting and edgy.

Michael Ray Charles: What is the effect?

Alison Stewart: What is your intended effect of the combination of those two things?

Michael Ray Charles: First of all, it's a language I think I utilize. I think that everything that we produce, that everything that is produced within a cultural context is language, and we always bring things to it. I bring somewhat of a romantic perspective because I love the original Wizard of Oz. Of course, you can't go home ever again and the click of the heels, and yes, you can. I like that and wanted to do something with The Wizard of Oz for some time, and, of course, The Wiz, because both of the films have very specific symbolism in terms of--

It's debatable whether the original has symbolism suggesting the Yellow Brick Road was some of the gold currency and the wiz the great migration from the south of African Americans north. I've always wanted to do work on and about with that idea. For me it's a question not unlike the every painting is titled Forever Free and signed with the penny with the great emancipator's image as a symbol of the ongoing question, what exactly is being free?

For me, that particular image is about the ungendering of Black males to a certain degree. Then the lingering question about being able to go home again with all the confusion about what home may be.

Alison Stewart: We've talked about it and mentioned the use of minstrelsy in your work. Do you remember the first time you saw one of those images a minstrel-like image?

Michael Ray Charles: I don't, but it was when I was a kid. I do know that when watching, Bugs Bunny or Tom & Jerry or those kinds of cartoons, the bomb would blow up in one's face and then wonder why or the cigar. For me, it's akin to slapstick comedy with just akin to the pie in the face. Then the cigar blowing off, and then the bomb, what is it? Roadrunner or maybe?

Alison Stewart: Wile E. Coyote.

Michael Ray Charles: Wile E. Coyote often happen to him, and always wondered why that was the case and why it was funny. As I grew older, I guess I started to put those things together, and it was the minstrel mask.

Later I found Mickey Mouse's version of completion of Uncle Tom's Cabin with minstrelsy, which was interesting. I think it was 31 or 33 Mickey's Melodrama, where, of course, Mini plays Little Eva, but Mickey Mouse was in the mirror dressing up for the play, the character Mickey Mouse, and lights firecrackers, and then boom, there's not only is Mickey now in a dress, but Mickey is also in Blackface, with the topsy like braids.

It was when I was young and I just didn't have the language. I didn't have the knowledge or understanding of it. You see it in movies, you see it in cartoons, and then I got to grad school and someone gave me a tiny figure made of plastic, and I just tossed it in the corner and didn't think of it having any relevance or significance. At that moment, I was looking for more authentic representation of America and the Black experience. I pulled it out of the trash and began to try and get beneath the surface of the mask. It took a little time, but with a lot of stick-to-itiveness, I've learned a lot.

Alison Stewart: What did you have to learn?

Michael Ray Charles: What did I have to learn? First of all, the past is present. The past is always present. The illusion that it isn't is part of, I think, a large problem in terms of how we deal with Black face, for example, which, in my opinion, is America's first creative contribution to the world. It started here. This iteration of it started here. It has influences that tie into Commedia dell'arte, which has its extensions in Roman theater. It goes back a lot further.

With the changing dynamics of perceptions of Black folks, Africans, in the 19th century, the appropriation of characteristics associated with Black people took a different turn. From that, and with that, a couple of stereotypical images that are influenced by antiquity, and changing technology, rapid dissemination of information and images, we enter into the 20th century bombarded with images that are not Black people, never were Black people. I think we are in a period of discovery now, and we are seeing past it. There are references in paintings and the show that signify that. That's that new generation I think I'm talking about.

Alison Stewart: Some people collect those collectibles, Black people collect those. I love thrift stores, and whenever I'm in a city in the south, or when I was a reporter and going around, I'd go to thrift stores, and I would see them. I would always turn them upside down as my little form of protest because I just really didn't like them. There was something about them that they were just out there made me mad in the moment that it was just like something to sell as opposed to something to think about. That idea of maybe things like that should be in museums in context, and in paintings.

Michael Ray Charles: Definitely in paintings. What was conceived in the mind of whites was believed in the mind of most Blacks, and unfortunately, it was given life. What if I told you they weren't Black people? There were in fact white people, an image of white people. That's one way that I try to look at it. Because I know it is not me, I could laugh at the absurdity and I could deconstruct it.

Now, I would say this, you got to keep in mind, throughout the 19th century, much of the early 20th century, Black people never had the tools afforded to them to be able to create an image of self-independent of whiteness and an image of self, a collective image of blackness that rival the perceptions of whiteness because of the power dynamics. We have that now, or do we?

Alison Stewart: That was my conversation with the artist Michael Ray Charles. His first New York show in decades, VENI VIDI, closes this Saturday, so you still have a few days to see it. Also closing this weekend is the Thierry Mugler exhibit at the Brooklyn Museum. That exhibition will end on Sunday. I had a great interview with the exhibition curators. You can check that out on our website or on your podcast app of choice.

Copyright © 2023 New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.

New York Public Radio transcripts are created on a rush deadline, often by contractors. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of New York Public Radio’s programming is the audio record.