Announcing February's 'Get Lit' Book: Tananarive Due's Horror Novel 'The Reformatory'

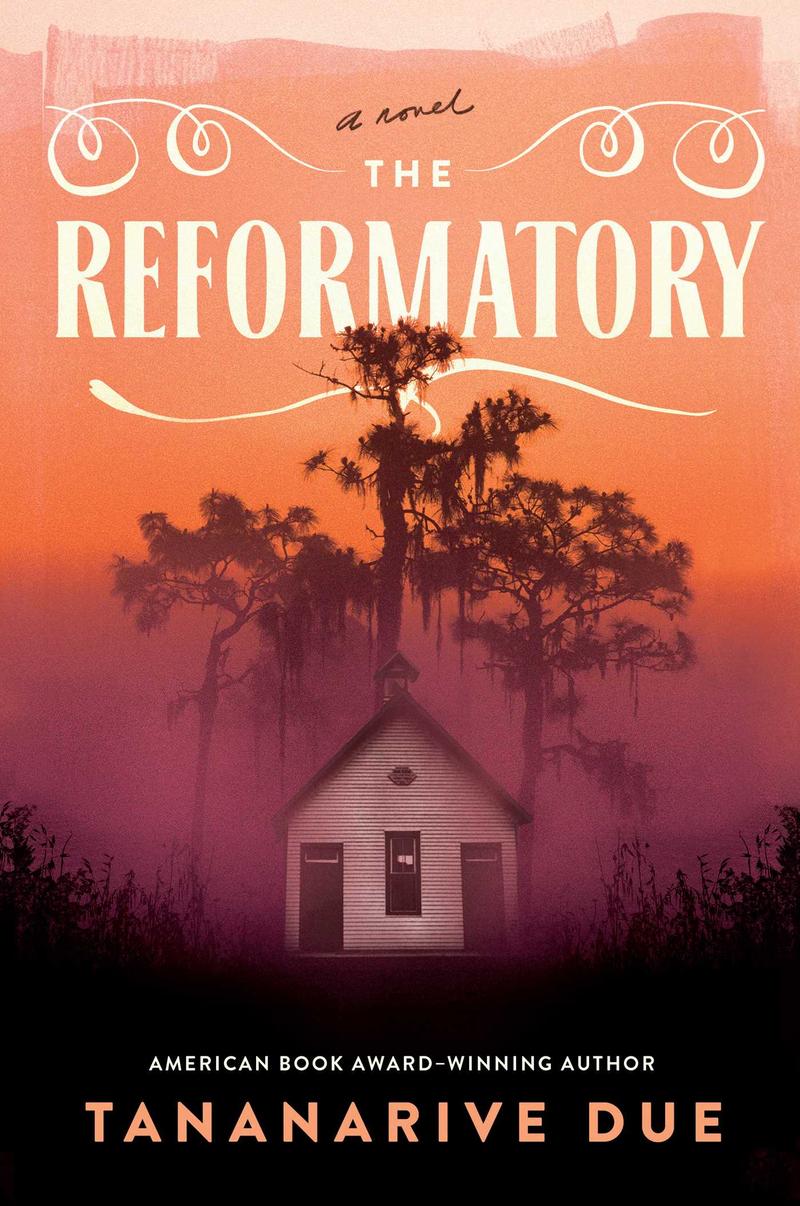

( courtesy of Simon and Schuster )

[music]

Alison Stewart: This is All Of It. I'm Alison Stewart, live from the WNYC studios in SoHo. Thank you for spending part of your day with us. I'm really grateful you're here.

On today's show, we will remember two Broadway legends who passed away, Chita Rivera and Hinton Battle. We'll also hear from the stars of the critically acclaimed dramedy, the musical Days of Wine and Roses. It just opened on Broadway. We'll also talk about ways to stay engaged with exercise and activity at all ages. New York Times writer Danielle Friedman, who recently penned the piece, How To Exercise When It Feels Impossible, will join us, and we'll take your calls.

First, let's get this hour started with some news about our Get Lit with All Of It Book Club, with our partners at the NYPL.

[music]

Tonight is our Get Lit with All Of It, January Book Club event with Michael Cunningham and musical guest, Josh Ritter. We've been reading his novel Day, and now it's time to gather together and discuss. We'd previously announced the event was sold out, but if you're listening and you really want to come tonight, it's your lucky day. Our partners at the New York Public Library have released 25 more tickets to the in-person event tonight at 6:00 PM at the Stavros Niarchos Foundation Library, on 5th Avenue and 40th Street. If you haven't been to that rooftop event space, it is much chef's kiss. It is gorgeous. If you want to snag them before they run out, head to wnyc.org/getlit. Do it right now. Twenty-five more tickets have just been released.

Reminder, for those of you coming tonight, seats are first come, first served. Doors open at 5:30. If you can't make it in person, you can always stream the event. You can find that link as well at wnyc.org/getlit.

Maybe you finished Day and you're eager to hear what's up next. Today, we are thrilled to announce that our February Get Lit with All Of It book club selection is, The Reformatory by Tananarive Due. The novel combines the real-life, terrifying facts about Florida's now-infamous Dozier School with unsettling supernatural elements to create a heartbreaking tale. You won't want to put this book down. The author has a personal connection to the real horror of that school. Her great-uncle was sent to Dozier and died there at the age of 15. The book is set in 1950s, Florida. Young Robert is sentenced to six months at the fictional Gracetown school, Gracetown is a stand-in for Dozier, after kicking the son of a powerful white man.

The leering young man was harassing and propositioning Robert's sister, Gloria. Almost immediately, Robert realizes this hellish "school" is horrible and it's haunted. Everyone there knows it. Robert, well, he can see and communicate with the troubled spirits of the boys who died there. The terrifying men in charge of the school, the kind who threaten and beat kids, see that Robert could be useful to rid the campus of the spirits, but at what cost to Robert.

Tananarive Due will be joining us for our February Get Lit event, on Wednesday, February 28th at 6:00 PM. You'll be able to grab your tickets and borrow your e-copy starting tomorrow, because tomorrow's February. You know that they sell out early, so maybe set a little reminder on your phone to head to wnyc.org/getlit tomorrow morning.

First to get you excited about the book, here's a little preview of the novel from Tananarive Due herself. I spoke with her about The Reformatory last November, and I began the conversation by asking her when she knew she was ready to tell this fictionalized story inspired by her great uncle's life.

Tananarive Due: From the first I heard of it, it was soon after my late mother passed away. We got a call from the Florida State Attorney's Office letting us know that we might have a relative buried at the Dozier School because the University of South Florida was beginning exhumations and they were looking for permission. My father, who was retired, and now he's 89, but at the time, he was about probably 79, we went to the grounds of the Dozier School for that first meeting.

In terms of when I knew, it was really pretty much at that first meeting. Seeing the survivors there, Black and white, it was a segregated facility, so they had not interacted with each other while they were there. They were trading stories, especially the infamous, what was called the White House, which was this whipping shed, which seems to have been an experience that it was very, very hard to avoid, and which clearly had left men into old age absolutely traumatized.

Alison Stewart: What was a detail that you learned about life at Dozier that you knew you would include in your novel?

Tananarive Due: Well, that's why I think the White House, or as I call it in the novel, the Fun House, is pictured on the cover because that is that one element that so many of them had in common. When I say whipping shed, I don't mean they were getting like paddled, okay? I learned from a survivor firsthand at that very first meeting that he was beaten so severely, and these are children, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14-year-old children that he had to cancel visiting day because he was in the infirmary, and that his clothes had been embedded into his skin by the whipping. They were whipping them bloody at a time when floggings were illegal for adults in the State of Florida.

Alison Stewart: In your book, Robert is our main character. What is Robert like before he's sent to Gracetown?

Tananarive Due: I really wanted Robert to not only represent my great uncle who died there at a little bit older at the age of 15, but I aged him down to 12 because I wanted him to be an every-boy. He's honoring my great uncle, but he's also the spirit of so many other children who were sent there for so many different reasons. Sometimes you were just an orphan. Sometimes you were just skipping school. I really wanted him to have that youthful superpower of adaptability that children have.

I write a lot of child characters, especially at that coming of age, like 12 years old when you're starting to figure out the world, but you're not quite a young adult yet. That's my sweet spot, because I wanted him to hold on to enough of his sense of hope and adaptability that it would be kind of a superpower to help guide him through this experience.

Alison Stewart: On one hand, Robert is someone who understands and educated about how to keep himself safe around white people. On the other hand, he's got this father who's now in Chicago. He was pushing boundaries in the small town by trying to unionize people. What do you think happened in that moment when Robert did something? There's no way it could end well. There's no way that a young Black boy kicking the son of a powerful white man could end well. What happened to the boy? [crosstalk]

Tananarive Due: Yes. Because of the trauma of having lost his mother the year previously to cancer, which mirrors our loss of my mother right before I started writing the book, and his father having been chased out of town and the instability. His teenage sister is raising him and doing her best, but there's a lot of instability and uncertainty. All of that boiled over, and Robert was just so confused when 16-year-old Lyle McCormick, who's like a high school football star and the son of the richest family in town, seems to be making a pass at his sister.

He couldn't even compute what he was witnessing, but on an instinctive level, he knew it was not good. He saw his sister speechless in a way he wasn't used to seeing her speechless. Well, first of all, let me just say, Lyle pushed Robert first, if I may say to the court but that doesn't matter. It doesn't matter because Robert kicked him and his father saw it. Sometimes we have those moments in life where you just if it had just been a little bit to the left or the right, a horrible, horrible thing wouldn't have happened. If Lyle's father hadn't witnessed it, he never would have been sent to the Reformatory. They would have settled it right there on the road.

Alison Stewart: My guest is Tananarive Due, the name of the book is The Reformatory. The Reformatory is called Gracetown. Usually, grace is associated with honor and showing dignity, and a lot of horrible things happened at this place. How did you come upon Gracetown?

Tananarive Due: Well, I started writing short stories set in my own personal Yoknapatawpha County. I studied a lot of William Faulkner when I was in college. A lot of readers, because I write horror, think I'm doing a Stephen King Castle Rock. No matter how you slice it, I wanted to create a magical town where children were especially impacted by the magic. Children can see ghosts, children can see creatures, and it represents that wild creativity that children have that a lot of us lose as we get older.

I named it Graceville originally, not realizing that there is an actual city in Florida called Graceville. I later changed it to Gracetown because I wanted it to be fictitious. I don't want anyone who lives in Graceville to think that this is their town. It isn't at all. It's really a combination of several Florida towns in Florida but with these magical elements.

Alison Stewart: The ghosts in these stories aren't merely ghosts. They're known as haints. What's a haint?

Tananarive Due: A haint is an old-timey word among Southern Black folks for ghosts. You find out in the course of this book that they don't like being called haints, but who knew? They consider it to be a bad name because it minimizes their experience, but yes, that's what haints are. The word has roots in Southern folklore.

Alison Stewart: Would you mind reading a little bit from the book so we can get a sense of the way Robert engages with the ghosts, or at least how he's aware of them?

Tananarive Due: Absolutely. I will read from a passage from Robert's first day at the Reformatory. He's not having a good day, but he's finally met a couple of boys in the kitchen he thinks might be friends, but now there's a strange white boy who's not supposed to be in the kitchen. He's very confused about that. Robert squeezed his eyes, shut tightly, opened them, and looked again, the boy stared on. Robert could see his cool blue eyes from across the room. He had never seen eyes so blue. A tiny clink rang as Redbone lifted a dripping plate he'd rinsed.

"Just tell him he ain't real and he'll leave you be," he said most times. "Not real? The boy was as real as he was," casting a shadow against the large metal vat. Robert could see his freckles. Blue spoke, hushed, "I've seen that white boy. The one with the knife?" Heart speeding, Robert checked to see if the boy held a knife. He was relieved to see the boy's hands empty, hanging limply at his sides. "He ain't got a knife," Robert said. "Must be another one then," Blue said. He checked the plates he'd stacked for chips.

"White boys must have worked in the kitchen before. They keep coming back," Redbone said. "I bet haints get hungry, huh, Blue?" "They must be hungry. They're punching open the rice and flour bags at night, and then we get blamed. That ain't right." "If you're dead, stay dead," Blue said. They could be talking about rats or roaches. "You're not real," Robert whispered toward the boy, attest.

As if Robert had shouted, the white boy turned to walk away, although he had nowhere to go except the back wall. A butcher's knife was buried in his back, the hilt lodged between his shoulders, blade shining in the light. The circle of blood was thick and black near the knife, soaking red down his back, leaving smudged footprints as he walked toward the wall. One stride and he was gone through the whitewashed bricks. Robert gasped, "He, he, he," Robert clung to the counter to stay upright. His words withered. "Yep," he heard Blue say, a tiny voice on the other end of a long tunnel, "Told you, Bone. Must be the one with the knife."

Alison Stewart: That was Tananarive Due reading from her book, The Reformatory. Robert doesn't just see the haints, he feels stuff. A few pages earlier, he says that Robert felt the boys dying, sharp pricks to his abdomen, neck, throat, then his back. He tried to rub away the stinging, swatting his skin like he was covered in bees. It happened before. Earlier, he felt fire from boys who had died in the fire. Is there a message for Robert specifically, since he's a person who is feeling what the boys felt, not just seeing them?

Tananarive Due: Well, yes, because I think the haints recognize Robert as a messenger. Not every boy in this facility can even see the haints. The school, just like the one in real life, the Dozier School in real life, had boys in prison from all over the state. Because Robert is from Gracetown, and he has that Gracetown blood and lineage, he's much, much more sensitive to seeing them than other boys there. Although other boys do sense them and see their mischief, Robert can talk to them. Robert can summon them. That is something very, very special, although frankly, it's probably a gift Robert could do without.

[laughter]

He's having a hard enough time dealing with his own misery instead of having to face the misery of others. It's an interesting twist in the story that enables him to actually have a kind of a friendship, I guess you could call it, with a ghost.

Alison Stewart: The way the story is written, and it's a fairly long book, but the first 100 pages or so, you really keep us at that first day with Robert. Why did you want to keep us in that first day at the Reformatory? After the kicking and all that, we're at the Reformatory on day one for a while.

Tananarive Due: I really want it to be a kid's eye, highly sensory view of what it would be like to be incarcerated at this place. This was where I really front-loaded a lot of the actual stories, testimonies, things that people had written about in their memoirs, things I saw on Facebook posts from people who had worked there, anecdotes. I wanted to make it as realistic as possible, even while I'm opening the doorway to the idea that there are these ghosts, because for the reader, I wanted much like Robert for them to understand that the scariest thing about this Reformatory is not the ghosts.

Robert was afraid to go there because he'd heard it was haunted. Ooh, but actually, I have news for Robert. The ghosts are not his biggest problem. I wanted the reader to understand that viscerally as well.

Alison Stewart: I thought it was interesting, there's a character who wants to help Robert, but he's a transplant to the South and he's Jewish. He has a moment when he could help Robert and Gloria early on, and he decides not to give Gloria, the sister, a card, his card, because he makes this decision, I guess, to look out for his own family.

Tananarive Due: Yes, the social worker, Mr. Loehmann, is one of the cogs and the machinery here who is just driving Robert to the Reformatory. He's heard some horrible stories, but he gives Robert some advice. He's telling himself that he hopes will keep Robert safe, while I think deep down, he knows it won't, and he's definitely, because this is soon after World War II. It takes place in 1950, and he has memories of his own family members who were shipped to concentration camps.

He's very bothered by what's happening, but at the same time, as a Jew who's just moved to the South, he's experiencing antisemitism and his children are being teased, and he's afraid his own house might get burned down, because I wanted to show the wider reach of the terrorism of Jim Crow. It's not just that Black families were terrified and terrorized. Allies were also terrified. There are limitations to allyship, even though there are several characters who in their hearts would want to help, they can't quite imagine how to do it in a way that would make them powerful enough or that would help protect them from violence against themselves.

Alison Stewart: My guest is Tananarive Due. The name of her book is The Reformatory. Robert's older sister, Gloria, is determined to do anything she can do to get her brother out of this situation. How does she find the strength to keep on fighting? She's a young Black woman on her own, virtually in the segregated South.

Tananarive Due: She's a teenager. It was very important to me that this be a dual story. Robert on the inside of the Reformatory, trying to fight his system, and Gloria on the outside, trying to fight the larger system. First of all, she's named Gloria, after my late mother, Patricia Stephens Due, who was a civil rights activist, and as a young person, 20 years old, was tear-gassed and wore dark glasses for literally the rest of her life, 80% of the time, even indoors, because of sensitivity to light.

We wrote a memoir together called Freedom and the Family: A Mother-Daughter Memoir of the Fight for Civil Rights, which is why I decided to set this story in 1950 because I could model Gloria literally after my mother, who would have been a little younger than Gloria, but what other kinds of things? Every time I had a situation where I felt overwhelmed and I didn't understand what Gloria should do, I just asked myself, "What would mom have done?" She would have done the wild outlandish thing. She would have thrown the Hail Mary pass to use a football metaphor, and she does that throughout the story.

Alison Stewart: Have you heard from anyone who spent time at Dozier about the book?

Tananarive Due: I have, as a matter of fact. I had an unexpected encounter actually at a signing. The very same day I spoke by phone with my father who's still living. There's an 89-year-old survivor. I actually found through his daughter, because they wrote a book together that I had not been able to read, unfortunately, before I wrote The Reformatory, but it's called It Still Hurts. His name is Salih Izzaldin. He wrote it with Marshelle Smith Berry.

I put him on the phone with my dad just thinking I would tell him, "Hey, guess what? I mentioned your book and my acknowledgments," but the first words out of his mouth were, "It still hurts." He was 12 when he was sent to the Reformatory. He was there exactly in 1950. At the time, his name was Robert. That was a bizarre coincidence.

Alison Stewart: Oh, wow. That was my conversation with Tananarive Due. She is the author of our now February Get Lit with All of It Book Club Choice, The Reformatory. We all love the book so much, so we wanted to make it next month's, February's choice. Already, people have started texting us. Someone texted to us, "Haints." I saw a mention in Southern Living/This Old House that people paint their porches certain colors to keep the haints away. If you're already texting about it, you can tell we all had a great conversation at our live event that's going to happen on February 28th. Starting tomorrow, you can reserve your tickets, and you can download an e-copy of New Yorkers, and of course, you can always pick one up at your independent bookstore.

Reminder, tonight is our January Get Lit event with author Michael Cunningham. We've all been reading Day. It is about one day in a family's life in April 2019, 2020, and 2021. It should be a great conversation tonight. As always, we have a musical guest. Tonight, we'll get to hear from Josh Ritter.

[MUSIC - Josh Ritter: Strong Swimmer]

Oh, the wind was in your hair

And your cheeks were flecked with salt

Your eyes were two boats for the moon

I said, "A strong swimmer, you'll be called"

Alison Stewart: This just in. The library has released 25 additional tickets. We were sold out, but if you want to come to the event tonight, it is your lucky day. 25 tickets were released just today. You better head to wnyc.org/getlit to grab them or find the link to stream online. That's happening at 6:00 PM at the Stavros Niarchos Foundation Library.

To play us out, here's a little preview of the musical performance that we're going to experience live in the room tonight. This is singer-songwriter Josh Ritter and his track Henrietta, Indiana.

[MUSIC - Josh Ritter: Henrietta, Indiana]

Henrietta, Indiana mill town

Locked the factory down and shut it up tight

My daddy and my brother and sixteen-hundred others

Lost everything they had in the night

Daddy got a taste for the hard stuff

Henrietta, Indiana was dry

We'd ride out to Putney, he'd tell me he loved me

The drive home was always so quiet

He had a devil in his eye, eye

Like a thorn in the paw

Disregard for the law

Disappointment to the Lord on high

My brother practiced preaching in the basement

Perspiration on his face 'til I knew

That something was missing, his spirit was willing

He could not believe it was true

"Blessed be the poor," he said

"Your treasure is on high."

All of Henrietta, Indiana heard me "Hallelujah!"

When I finally saw the devil in his eyes

Oh, the devil in his eye, eye

Like a thorn in the paw

Disregard for the law

Disappointment to the Lord on high

I was coming home late

From a midnight to eight

The radio said they'd ID'd the plates

Left three men dead

Made their escape

"By now," said the sheriff

"They'll be in the next state."

"Will we be able to catch them?"

"Can they bring the dogs in?"

"Can they call up the Bureau?"

"Do they have next-of-kin?"

Cameras came to my door

I opened it wide

They thought I was crying

It was something--

Copyright © 2024 New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.

New York Public Radio transcripts are created on a rush deadline, often by contractors. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of New York Public Radio’s programming is the audio record.