Analyzing the Suicidal Mind with Clancy Martin (Mental Health Mondays)

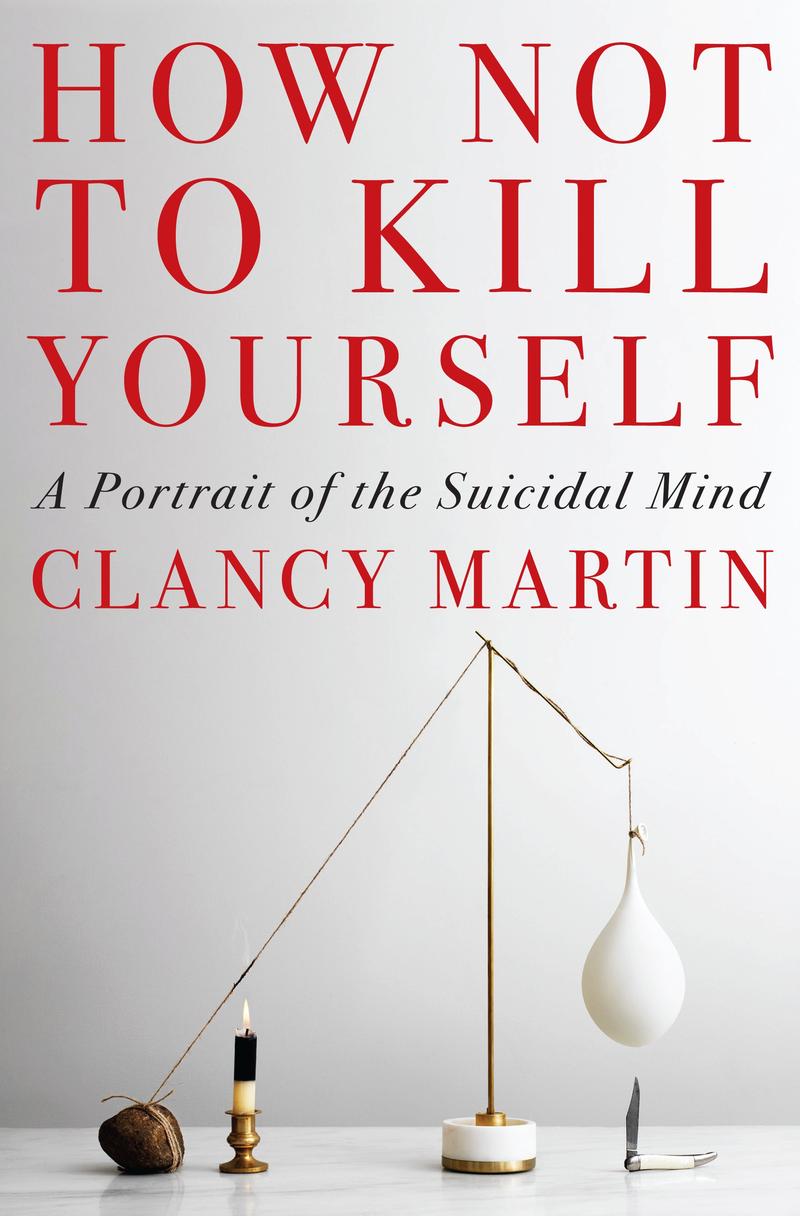

( Courtesy of Penguin Random House )

[music]

Alison Stewart: This is All of It. I'm Alison Stewart live from the WNYC Studios in SoHo. Thank you for sharing part of your day with us. We have two important conversations this hour. It's decision day for many high school students, the choice of where to matriculate is huge and imagine what that might mean for a Black queer teenager. We'll dig into that subject with Wellesley Professor and Dean, Michael Jeffries. May is Mental Health Awareness Month, and every Monday we're going to talk about it. We're going to have Mental Health Mondays.

We're planning conversations about burnout and music for mental health. We're kicking off today's Mental Health Monday conversation with the serious discussion about what can happen when hopelessness is not addressed. Listeners, I want to let you know that this conversation is going to be dealing with suicide. If at any time you feel you need support, please text or call the National Suicide & Crisis Lifeline. That number is 988. Just text or call 988, it's open 24 hours a day.

You may have seen the heartbreaking report about a 17-year-old boy, a student at New Jersey's elite Lawrenceville Prep School taking his own life over the weekend. As reported by the New York Times, the school's administration officials acknowledged knowing of the student being bullied and that they could have done more for him, and they would do more in the future.

Not talking about suicide deaths is part of the problem according to our next guest, professor and author, Clancy Martin who knows a lot about the subject. When writer and philosopher, Clancy Martin, was just six years old, he decided he wanted to end his own life. He snuck out to the busy road in town, waited for a bus to approach, and stepped into traffic. He managed to walk away with his life, but this attempt was the beginning of a decades-long struggle with suicide attempts and suicidal ideation along with debilitating alcohol addiction.

In a candid, compassionate and helpful new book, Martin writes vividly and analytically about the experience of living with the desire to die. It's titled How Not to Kill Yourself: A Portrait of the Suicidal Mind. Part memoir, part philosophy lesson, part literary analysis and part resource guide, the book provides an honest and hopeful accounting of a stigmatized topic, which is why it's perfect to begin our ongoing series for May of Mental Health Mondays.

Martin writes, "I hope that anyone who is in some way orbits the dark sun of suicide may be helped a bit by reading about my own attempts, my failures, and successes to live with that gravitational pull." Clancy Martin, welcome to All of It.

Clancy Martin: Thank you so much for having me.

Alison Stewart: I want to address this upfront before we start the conversation. There have been multiple studies done about the impact of exposing people to death by suicide, and the studies focus on media reporting on suicide, suicide clusters, the impact of adolescence with exposure to a suicidal peer, sometimes people call it suicide content contagion. What are some of the ways that you knew you had to be careful when writing about suicide and how we should be careful in this conversation today?

Clancy Martin: Yes. There are two opposed effects that we know of that we should be aware of when we are writing or talking about suicide, especially in public venues. One is generally called the Werther Effect after Goethe's novel. There are a bunch of copycat suicides after The Sorrows of Young Werther came out. We know that if a famous influential person attempts suicide or especially dies by suicide, and it's widely publicized that the suicide rate will go up. There's another effect called the Papageno Effect after the character of Papageno in Mozart's The Magic Flute, who is thinking about suicide and then changes his mind when he gets a variety of different kinds of advice from his friends.

What we find is that when someone makes an attempt or dies by suicide, and the media really gives a robust account of what happened, how that person came in to the position where they were making a suicide attempt or driven to an actual death by suicide, all the various factors that were involved, that the suicide rate actually goes down. Journalists, other people who are willing to speak about suicide, and speak about it in an informed way have this amazing power to save lives if they do this responsibly. What we mean by responsibly is really just trying to tell the whole story. Talking about how suicide is almost never a spontaneous act. It's almost always the culmination of years of struggling against suicidal ideation.

Resources, of course, are important to mention and also, very, very simple things are important to talk about that are beyond the normal things when we think of professional resources. The best medicine we know of for helping someone with suicidal ideation is just reaching out to that person, just initiating a conversation. Not trying to solve their problems, but just asking them questions about how they're feeling. That is the single best way we know of for saving lives and preventing death by suicide.

Alison Stewart: What's the purpose of your book?

Clancy Martin: The purpose of my book is first and foremost, to speak to people like me who suffer from chronic suicidal ideation and have made a failed suicide attempt. Unfortunately, the best predictor of a death by suicide is a previous suicide attempt. These people urgently need our help and they need to know that they should not be ashamed that they failed to commit suicide.

It will sound really weird to some years, but the characteristic feeling of someone who has failed after a suicide is regret, and shame, and disappointment, especially when you first realized that you failed. You're just like, “Urgh.” You feel miserable, that you failed and you feel really ashamed and embarrassed that you failed, and you can’t-- You think about the consequences of everybody you're going to have to talk to and you can't bear it. Then they probably hold you on what's called a 5150 Hold in the psychiatric hospital, or these days, you're lucky that you get into a psychiatric hospital. It might just be an emergency room for three days and then they release you, and that is when you are actually at the greatest risk of death by suicide. To reach out to those people and say to them, "You have nothing to be ashamed of, and here are some ways you might think about starting to help yourself with chronic suicidal ideation."

I also want to talk to the loved ones of people who have lost people they care about to suicide and say, "You're not to blame. This was not your fault. You probably were the person who was keeping that person, the person who died from suicide by making attempt for so many years. You probably were providing all kinds of help that you didn't even realize that you were providing, so don't blame yourself."

Then I do want to also talk to the larger-- to all the rest of us. According to the World Health Organization, 10% of the world population suffers from chronic suicidal ideation. We know that statistic is low because there's such widespread stigma that people are not willing to report that they're suffering from chronic suicidal ideation. If we've got 7 or 8 billion people living on the planet, that's 700, 800 million people living with chronic suicidal ideation, then if we had good statistics, probably double that.

We have got to reduce the stigma. We have got to reduce the taboo and acknowledge this so that people can talk openly with one another and consequently learn ways of managing their suicidal ideation, and it can be managed.

Alison Stewart: Yes. You divide the book into three sections. The first address is how someone becomes suicidal. The second shows what a person in crisis looks like and the third in your words, how to move beyond the need to kill ourselves. I was very curious about that word need, the need to kill ourselves versus wanting to kill oneself. Why the word need?

Clancy Martin: Right. Well, I'll tell you that when I was a kid and then as I was a teenager, among my earliest memories is not just the desire to kill myself, but really the drive to kill myself. It's best described as the need to kill myself, much stronger than a wanting, but a need in the same way. Freud talks about this, and he got it from the Buddha that the need for self-annihilation, what he calls the death drive, is just as powerful as the need for sex or the need for food, these things that are associated with the drive for life.

When I first encountered people and talked to them and realized that they didn't feel the same need to die that I had, I didn't believe them. I thought they were making it up. I thought they were just lying to my face. Then as I got into my 20s and I met more and more of these people, I thought, the depth of self-deception is amazing. They all share the same need that I have but they're just not admitting it to themselves.

Then it only, it was really in my 30s when I realized, there are people who are walking around their ordinary days and they're not just feeling the need to- -kill themselves all day long. It was a revelation to me, quite honestly.

For me myself, the need didn't really start changing until a want, until later as I came out of the real crisis period of my life, and then the want started turning into I'm grateful to say something more like a suspicion of, or a distaste of a thought that nevertheless occurs over and over again. And I expect will occur for the rest of my life that the plot comes into my head, “Oh, I should kill myself.” For the longest time, that seemed like a really good idea. Now I'm happy to report it seems like a bad idea. But, yes, it's not until the need turns into a want, and the want turns into something else that you start to experience a little bit of liberation from this urge.

Alison Stewart: I wanted to ask about one more bit of language before we move into details in the book. I've heard you in interviews and sometimes in the book use the phrase ‘committed suicide’, which many mental health advocates don't use anymore. Why that choice?

Clancy Martin: Well, because I fell that-- I wrestled with this question of course, and in general I talk about dying by suicide just because so many people in the Zero Suicide Movements, the movement that has the goal of eliminating suicide if possible, and at least dramatically reducing it, which I think is an achievable goal. I think we can dramatically reduce suicide. They do avoid this language because they feel like the language ‘commits suicide’ and they're right. It has a stigma attached to it.

The reason I don't just completely avoid the language is I really feel like once we start controlling the language around this topic and telling people how they are allowed and not allowed to talk about it, we are without meaning to contributing to the stigma, contributing to the taboo. We're controlling a conversation that we don't need to clamp down on. What we really need to do is open up a little bit. I see the movement is working in some ways parallel to the transformation of Alcoholics Anonymous into many, many different kinds of 12 step programs we have today that don't rely on anonymity in the same way, and don't rely on this somewhat dogmatized language. I just feel like we don't want to control the language more than necessary.

Alison Stewart: My guest is Clancy Martin. We're discussing the book, How Not to Kill Yourself: A Portrait of the Suicidal Mind. If you're just joining us, this conversation is about suicide. If you need support at any time, please note the National Suicide & Crisis Lifeline's available to you at 988. Clancy, you dig into this idea that some people talk about attempted suicide as a, we've all heard it, cry for help. Share where you stand on this.

Clancy Martin: Yes. The first thing that we must say is that the best predictor of a suicide attempt is someone saying-- what we say, the language we use, threatening suicide, someone saying, "Hey, I'm thinking about suicide." Every time, anytime someone mentions that they might be thinking about suicide to you or that this thought has crossed into their head, you have to treat this with the utmost respect and seriousness and never dismiss that language. That is someone reaching out to you, even if they're doing it in a casual or joking way.

When they do that, ask them how they're feeling. Crucially, don't try to solve their problems. Just try to get that person talking and continue to ask questions about how they're feeling. You might ask them if they have a plan, but you don't necessarily have to go to that question right away either. The key is to let them know that you care about them, that you're there for them, and that you are wanting to hear about how they are feeling. Eventually, of course, the conversation might want to come around to saying, "You know, we could think about putting you in touch with this therapist or that therapist."

I talk to a lot of these people and people like me who are reaching out. Thank goodness. It's so wonderful when someone reaches out to you. It's an incredibly brave thing to do and--

Alison Stewart: How did you respond when someone did this for you during your period was-- [crosstalk]

Clancy Martin: When I--

Alison Stewart: Yes, when you would say out loud to someone in your orbit.

Clancy Martin: Well, I'll be honest with you. I've had all different kinds of reactions in the course of my life. I've had people greet this language with frank skepticism, or even mockery, or condescension. I've had people like my dad just straightforwardly said, "Son, you can't do it. You'll go straight to," what he called, "the Astral Hells." He was this New Age guru type. “You'll wind up someplace much, much worse.” Not because he thought it was some punishment, but because he thought that doing a violent act that ended your life, your consciousness continued, but your consciousness continued in a much more disturbed state.

Then I've had people say, "What's got you so down? What do you think has put you in this place? Why do you think you're feeling this way?" That last question is the question you need to ask people, like, "Okay. Tell me. Tell me more. What's going on? What's got you feeling this way?" I've had every kind of reaction, and I'll tell you if someone reaches out and you treat their reaching out with skepticism or mockery or something like this, it's a really, really, really bad idea. Just don't do it.

Alison Stewart: My guest is Clancy Martin, author and professor of philosophy. The book is called How Not to Kill Yourself: A Portrait of the Suicidal Mind. We'll have more with Clancy Martin after a very quick break. This is All of It.

This is All of It on WNYC. I'm Alison Stewart. My guest this hour is Clancy Martin. He is an author and a professor of philosophy. His book is called How Not to Kill Yourself: A Portrait of the Suicidal Mind. It's our first installment of Mental Health Mondays. This conversation is dealing with suicide, so if at any time you need support, please call or text the National Suicide & Crisis Lifeline at 988.

You were very honest in your book that you have lived with thoughts of suicide pretty much your entire life, Clancy, What do you wish more people understood about what it's like to live with these kind of thoughts, but not necessarily even acting on them, but to live with them for a long period of time?

Clancy Martin: Well, Alison, the first thing that I would like people to know is that these thoughts are much, much more common than people realize. That you can go through a period of really serious suicidal ideation and then that period of suicidal ideation might diminish. Suicidal ideation is similar to depression in some ways. One thing that is really important for people to know when they get depressed or when they're in a period of intense anxiety is that there was a time before I was so depressed, there was a time before I was so anxious and there's going to be a time after and that these things come in waves.

For someone who is suffering from suicidal ideation, I think it's really important for them to try to expand their perspectives to know that it's not necessarily always going to be that way. Now for people who suffer from suicide ideation, and it seems like it's just, "Okay, I've always suffered from this and maybe I'm always going to suffer from this." I think it's really important to know that thinking about taking your own life is a thought like any other thought. You have all these thoughts that are in your head and the vast majority of them you don't act on.

Some of them are terrifying. Some of them are horrible. Some of them are very pleasant and some of them are merely attractive. Anyway, your head is full of all these different thoughts. When the thought of taking your own life is there and it's getting more and more prominent, don't feel that this is somehow a different character than those other thoughts. It's just one more thought. What you might even do, and what has been very helpful to me, and I know has helped a lot of other people, you might even take that thought and treat it like a little baby and say, "Okay, here you are. I recognize you. I've seen you before. I'm going to see you again. I'm not going to act on you, but I'm just going to hold onto you and let you--" Don't hold on too tightly, I guess. Be ready to let it go when it goes, “But I'm just going to take care of you and let you be.”

Acknowledge- -the thought, and have care for the thought. Don't be afraid of it. Don't run away from it. Don't try to suppress it. Let it be and don't act on it and then it's going to go away. This is an amazingly helpful technique.

Alison Stewart: I've heard psychiatrists say that as well, that idea of it's there are many thoughts we have.

Clancy Martin: Yes. We have so many crazy thoughts in the course of a day. Some of them are habitual thoughts and a lot of them are habitual thoughts that occur over and over and over again. It doesn't mean we act on them. We don't have to be menaced by them. The thought of suicide feels very, very menacing when you have it and sometimes it feels totally irresistible. Now when it feels totally irresistible, let me give you a little more advice. In that case, the best thing you can do is reach out to someone, but if you feel like you can't reach out to someone, there are a few other things you can do.

Do anything that will lighten the pressure a little bit. For me, for example, walking always lightens the pressure a little bit. Do anything that will lessen the pain a little bit. It's a very, very painful thought. It can be one of the most painful thoughts you'll ever experience, an extremely acute pain. When David Foster Wallace talks about it, he says, "What people don't understand is that people who take their own lives, it's like standing in a burning building. They don't want to jump out of the burning building. They're just more afraid of the flames behind them than they're afraid of the jump.” I think it's a good analogy.

It can be in incredibly painful. What can you do to lessen the pain? There are lots of things that I do when the pain is really super intense. Sometimes listening to a Jimi Hendrix song will actually lessen the pain for me a little bit. Definitely walking will lessen the pain. Making myself a cup of tea will lessen the pain. Talking to-- texting usually for me. Talking doesn't work as well for me but if I text any friend. It could be my roofer. I could send my roofer a text, "Hey man, I'm kind of stressed out." Then he sends me a text back. It lessens the pain a little bit.

Then the other thing, you got to remove the blinders a little bit, which again, can be hard, but the pain can be so intense that you start feeling like your choices have gotten so narrow, that now it's narrowed down to only one choice in front of you. A lot of people who write to me about suicide, that's exactly the language they use. Now you have to ask yourselves, "Okay, I can only see this one choice, but are there any little things I can do that could help me to see that no, I do have other choices?" One good thing is definitely to change the immediate physical environment that you're in, and sometimes a good thing to do.

John Draper, who's a wonderful-- he's one of the people behind this 988 mental health line and is a fantastic guy. He's like a [unintelligible 00:22:58]. He is got a light around him. He saves so many lives. John Draper said what he always tells people is that what feels like a boulder is just a whole bunch of little rocks. Sometimes if you just take one little rock off, that will lower the blinders a little tiny bit and you see that, "Okay, I do have some other choices."

Alison Stewart: In the book, you are very candid about-- you have a wonderful personality and you sound very bubbly, but in the book, you get into some of the darkest times. You write about waking up handcuffed to a gurney. You talk about a failed attempt where you hurt your throat in a really dramatic way. I don't want to get into the details that maybe needs to be read in context. You also, you write your really turbulent childhood. Your father was diagnosed with schizophrenia, was abusive to your mother. Your mother left your father for his AA sponsor who had seven children. It was just a lot going on in your life.

When you think about the environment you grew up in, do you place any weight on that influencing these thoughts that come to you and have come to you their whole lives?

Clancy Martin: Alison, we know from the, there's some excellent research. A lot of it has come out of the Netherlands on the neuropsychiatry of people with chronic suicidal ideation and people who've died by suicide. We know that one of the best predictors for suicidal ideation and death by suicide is childhood trauma. I'm quite sure that my childhood impairment was not helpful to the thinking that has led to my many failed suicide attempts. It's definitely relevant.

For me also, what I've had to do is say, "Okay, Clancy, you had the childhood that you had. You can't go back and change that childhood so what are you going to do now? Are you going to drink yourself to death?" which I tried to do for a long time. That's what we call parasuicidal behavior and it's how lots of people do die. For wonderful Amy Winehouse, that's how she died. It's a form of suicide. "Or are you going to try to find some way out of this?"

One story that, one time I was so depressed and I was on vacation with my family down in Mexico. I was not drinking at the time. I was on a lot of different medications and the depression, I hadn't yet learned how to manage my psychiatric medications and some of them I think were really making things worse for me. I was so depressed and so I decided that I was just going to swim out to sea until I was too exhausted to keep on going and then I was going to-- and I had tried this method more than once.

Once more, I got all the way out there and I just, I tried and tried and tried in the ocean, diving down over and over again, trying and I just couldn't do it. I’d panic, I’d pop back up and then finally, exhausted beyond exhausted, I swam back to sea, I mean, swam back to shore.

Well, the next day, my daughter, who was with me at the time and who was in her early teens wanted to go swimming. She said, "Let's go in this beach." It was the very beach that I'd tried to take my own life on the day before. We went out swimming. She got caught in a riptide. She was being pulled out to sea. She's not a good swimmer. I also am not a good swimmer, but I somehow managed to pull her back to the shore. Then we were laying there on the shore crying and laughing. I realized, my God, I just saved my child's life.

So many people who've talked to me about this, who have also had a lot of childhood trauma have said, "This is what you have to do. You have to recognize that now you have this opportunity to try and break the cycle so that your own children don't have similarly traumatic experiences.” Now, they had an alcoholic, suicidal dad. I have to say that, I don't know how much success I've had at breaking this cycle. They seem to be doing great but I keep a real close eye on my five children. I at least try to let them know that, "Hey, if you're ever having these thoughts, you've really got somebody who can talk to you about these thoughts. Your dad knows what it's like to be depressed, to be anxious, to feel like taking your own life."

Alison Stewart: My guest is Clancy Martin. The name of the book is How Not to Kill Yourself: A Portrait of the Suicidal Mind. We have Jennifer who's called in and wanted to make a comment. Jennifer is first calling in from Manhattan. Jennifer, thank you for taking time to call today.

Jennifer: Thanks very much for taking my call. Dr. Clancy, thanks very much for what you've done. I think that one of the great misunderstandings about suicide is that it's not so much that people want to die, it's that they're having a desperately hard time living. I think that the whole mental health crisis that we're seeing reflects the fact that life is very difficult and increasingly so we have a loneliness epidemic. We have a breakdown in community and family in so many of the areas that really are required as foundations for a positive and constructive life.

I do think, and as somebody with an academic background in psych and mental health areas, I think the focus really has to be shifting towards, how do we make living more supportive and recognize that suicide is a recognition of the difficulty, not the desire to die. I'll take your response off the air. Thank you so much.

Alison Stewart: Clancy?

Clancy Martin: Jennifer, I hope I have that right. Jennifer, I think it's just a wonderful comment. Thank you so much. I think it's particularly relevant for some groups that we really ought to be worried about. As I'm sure Jennifer knows, right now, adolescents, their rates of suicidal ideation and their rates of attempts are skyrocketing in this country, and they're simply not getting the help they need. They very often are sitting in emergency rooms for two, three, four days and not seeing a mental health professional and then being released.

Among LGBQT populations, 40% of that population will make a suicide attempt. It's a terrifying statistic. Among minority populations in this country, suicide attempts, which have been increasing for about the past 10 years or so have been skyrocketing and- -for all these four reasons that Jennifer mentions. Also, the highest rate of death by suicide of men my own age and older, white men in their 50s and 60s.

I think there again, these men are dying by suicide at the high rates that they are because of a lack of appropriate social support in particular. I agree entirely with Jennifer. I don't think there's any question there. We're in the middle of a mental health crisis and it's expressing itself in terms of suicidal ideation and suicide rates, and we have to take it seriously.

Alison Stewart: Clancy, you're a philosophy professor. There's a lot of philosophy throughout this book, which is really interesting and chewy. If you could point listeners to a philosopher, one or two philosophers you think has something really valuable to say about suicide or about mental health issues, where would you point someone?

Clancy Martin: Well, there's an argument from the stoic philosopher Seneca that I always mention. I don't of always mention that it comes from Seneca, but I always mention it when I'm talking to people who come to me in crisis. Seneca didn't come up with it, it predates Seneca, but it's the argument that the door is always open. What is meant by the door is always open is that, look, you have this power. You do have the power to take your own life if need be. Why that power is so important is that if you are in terrible pain, that opportunity is there for you, but it's there for you in my mind so that you don't have to take it.

You could wait. You can say, "Okay, if it gets that much worse, I could do this tomorrow. Tomorrow I can do it. The door will still be open. I don't have to do it today. I can breathe through this pain for one more day and then if necessary, the door will still be open tomorrow." This argument has really worked well with me arguing with myself and also with lots of other people that I have spoken to. It's the argument that the wonderful Romanian philosopher Cioran also always used when people came to him talking about suicide.

He said, "Look, you're free to kill yourself anytime you like, so don't be hasty about it. Wait a day or two, really think about it." A day or two goes by, and as Cioran also said, and they think about it and then they very, very frequently change their minds. It gives you room to breathe.

I liken it to one time I was in a DUI prison. It was a three-day thing, but at this prison, they told you you were free to leave. They showed you the door you could leave from. I suffered from terrible claustrophobia when I was locked up, either in a psychiatric ward or in a jail, which has happened to me quite a number of times, both from suicide attempts and from my alcoholism. At that particular place, because I was free to walk through the door, I had none of the claustrophobia at all.

That tiny attitudinal difference that I knew I could leave, even though I'd be arrested as soon as I did, made just a world of difference. This is why I think this argument is so helpful to people. It lightens the pressure. It gives them the little bit of room they need to breathe.

Alison Stewart: Yes.

Clancy Martin: The other philosopher that I would really recommend to people who are struggling with this is Thích Nhất Hạnh. Thích Nhất Hạnh the Buddhist philosopher who died just a year or two ago, he takes the desire for self-annihilation as he puts it, very seriously. He thinks it's one of the fundamental sources of suffering. He gets this from the Buddha and he just has so many different helpful techniques for dealing with the desire for self-annihilation. In some sense, his entire literature, which is enormous, is dedicated to this problem. If you're struggling right now, do me a favor, watch the YouTube video of Thích Nhất Hạnh talking to Oprah Winfrey. Just watch that YouTube video and it will save your life. I can almost guarantee it.

Alison Stewart: Clancy Martin is the author of How Not to Kill Yourself, A Portrait of The Suicidal Mind. If you've been listening to this conversation and at any time you need support, text the National Suicide & Crisis Lifeline at 988. There's some great resources in Clancy's book as well. Clancy, thank you so much for being with us and being so candid.

Clancy Martin: Oh, it's been my great honor, Alison. Thank you so much. I'm completely thrilled to have been on your show. It's a fantastic show.

Alison Stewart: This is All of It.

Copyright © 2023 New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.

New York Public Radio transcripts are created on a rush deadline, often by contractors. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of New York Public Radio’s programming is the audio record.