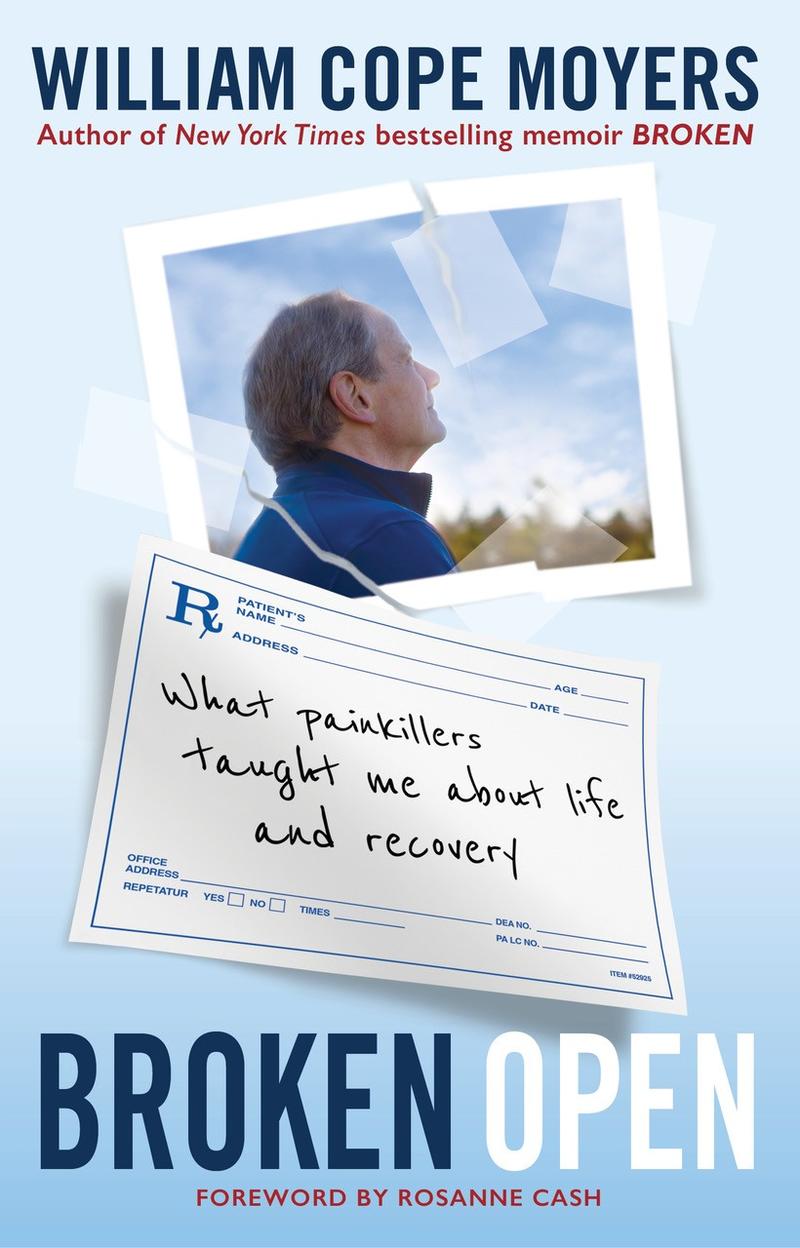

William Cope Moyers on Recovering From Painkiller Addiction

( Courtesy of Hazelden Publishing )

Alison Stewart: This is All Of It on WNYC. I'm Alison Stewart. William Cope Moyers was a success story within the addiction community. He was a public advocate for one of the leading treatment centers, the famed Hazelden Betty Ford Foundation. It was a long way from his rock bottom spending time at a Harlem crack den, his well-known parents, journalists, Bill, and Judith Moyers, not knowing what to do.

Moyer's story of Taylor taking back his life was captured in his 2006 book, Broken: My Story of Addiction and Redemption. He was an advocate and a proponent of seeking help for substance abuse until a trip to the dentist put him in contact with painkillers. He took one and then another and another. He writes in his new memoir, "Alcohol has consumed me. When I was a kid in college, cocaine had eaten away my teeth and ruined my relationships as a naive young man, and in these past years, when I was older and should have been wiser, painkillers had invaded my life in a eroded my integrity.

Once again, I was dancing at the edge of an abyss that threatened to destroy me and everything I believed in, everyone I loved." His book is called Broken Open: What Painkillers Taught Me about Life and Recovery, andWilliam joins me now. Nice to meet you.

William Cope Moyers: Thanks for having me on the show, Alison.

Alison Stewart: Listeners, if you would like to join our conversation, we'd love to know, are you in recovery? What has helped you get through the day? Our Phone number is 212-433-9692, 212-433-WNYC. In your first book, Broken, you covered your addiction from your early pot use to cocaine. Then the book picks up here after your memoir's release. What did you learn about yourself once the book came out? The first book?

William Cope Moyers: That my story matters and that when I share my story of addiction and redemption, I smash the stigma, I raise awareness about the truths of these issues, and most of all, I help other people who are struggling. Lots of us struggle with substances. When I shared that story in Broken, it was a true story, it was accurate and it helped a lot of people. I realized during that process, Alison, that I had a responsibility and I had a role as the employee I am at Hazel and Betty Ford, but also as a public advocate for people who may never get to Hazel and Betty Ford, a role to help people find hope and recovery along their own journeys.

Alison Stewart: What did people talk to you about after they read that book?

William Cope Moyers: A lot of them said, "William, I want to be like you one day," and I was like, "Be careful what you ask for," but seriously, people wanted what I had, families wanted what my family had, which is a way out. Addiction is a stigmatized illness, there's not enough in the way of access to care, and recovery is kind of a squishy thing, as I was to discover. The most important takeaway was that people wanted what I had, and they wanted to know how to get there. Of course, as the public advocate, I helped direct lots of people to a solution.

Alison Stewart: You were very open that you grew up with all the things. You grew up with, the money and privilege, loving parents, but you had sort of a hole.

William Cope Moyers: Yes.

Alison Stewart: In your prologue to your book, Roseanne Cash, wrote the prologue, and she cites your description of worthiness, hustling personality. What does that mean, and how does that open the door for substance abuse?

William Cope Moyers: Addiction is an illness of the mind. I have a genetic vulnerability to substances, as many of us do. Then I also have what I call a hole in the soul. I think all human beings have a hole in the soul. It's called yearning. It's why we want to be creative, why we want to be a host on public radio, why we want to write a book, why we want to run a marathon.

My yearning was about something that was unachievable, and it was perfectionism. I always wanted more than what I had in the sense of recognition and accomplishment. Yes, some of that came from the fact that I come from a family of successful journalists, Judith and Bill Moyers, as you noted, but mine was all about what the big book of alcoholics, synonymous, describes as being restless, irritable, and discontent in my own skin. I never felt adequate enough. I always felt I needed to be more than I could be, which was to be perfect.

I found the solution to that when I used substances because suddenly I didn't have to try so hard anymore. The problem with it is I have a vulnerable brain, and when I started using, I could not stop of my own free will.

Alison Stewart: You spent the first few years in and out of recovery. It started with this night in Harlem. You write about it, 1989, in a crack den. You were off and on until October 12, 1994. What happened during that period of you going in and out?

William Cope Moyers: Good question. I struggled with the chronic disease of addiction. A lot of people want addiction to be cured when they send their loved one to treatment or when they themselves go there. There is no cure for addiction any more than there's a cure for diabetes, hypertension, or depression. For the first five years between '89 and '94, I struggled with this desire to be cured of addiction and yet not willing to do the work to keep it at bay or to keep it in remission, so I was in and out of treatment four times over five years between '89 and '94.

Then on the morning of October 12th of 1994, I came out of a crack house, as I tended to always end up in those things in Atlanta, Georgia, where I was working for CNN, and I decided that, "You know what, Moyers, your way is not working anymore, so you better do it the way that the experts say," and I began to work my program of recovery and I found sustainable remission.

Alison Stewart: My guest is William Cope Moyers. We're talking about his book Broken Open: What Painkillers Taught Me About Life and Recovery. If you'd like to join this conversation, our Phone number is 212-433-9692, 212-433-WNYC. Are you in recovery? What has helped you? Our phone number, 212-433-9692, 212-433-WNYC. You wrote in this book you learned the difference between recovery versus sobriety. What's the difference?

William Cope Moyers: Ah, such a question. You know what, we're all going to have different perspectives on that, but here is mine, what I have discovered because I had my "run in with pain meds," I began to use substances again, in this case, specifically opiate pain meds that were appropriately prescribed at the time. All during that time, Alison, I struggled with my sobriety as I'd always defined sobriety, which is right, being free from substances.

What I learned along that struggle and along that course of action was that for me, and only for me, the way I define it, there is more to my recovery than sobriety. Now, sobriety is a good thing for a lot of us. It's a necessary thing for people who can't control their youth, but that three year period, which I talk about in Broken Open was a period when I wasn't sober in the way I had defined it, but I was still holding on to the hope of my recovery to be a better man, to be a decent human being, to be a good father, to show up at work, to be a good advocate, and all those other things that I had defined by my recovery.

That's where I began to parse the fact that for me, there was more to my recovery than sobriety, since I couldn't regain my sobriety yet I still held on to my recovery.

Alison Stewart: I'm curious, before we get into your problems with opioids that what was life like for you in that 20 years of recovery and you become the face of success?

William Cope Moyers: I looked good on the outside, and I had a lot of success. My first memoir, Broken, is a snapshot of my Life up to 2006. It's accurate, it was current at the time, but the rest of my life happened after 2006. The run up to 2006 was what I would call a V-shaped recovery. I went down, I hit my bottom, and I went back up, but I didn't live happily ever after. Very few of us do.

During that period of time when I was sober and in recovery, big chunks of my life were falling apart. I discovered what it was like to be an imperfect spouse. I discovered what it was like to struggle with a spouse who had mental health conditions. I discovered what it was like to suffer with a broken heart. When my wife at the time decided she didn't want to be married anymore, I decided what it was like to raise three busy teenagers as a single dad. I had a very busy life, I had a very good life, but I had big pains in my life that ultimately I thought I had found some relief for when I started taking those pain meds.

Alison Stewart: Before we talk about the opiates, there's something that I thought was really interesting in the book is that in your life as a public advocate, you fought against the way that people with substance abuse were discriminated against. Could you explain to people how that could come to reality? People like, "Oh, I'm sorry, you're substance abuse or you might be an addict," and then what could happen?

William Cope Moyers: Yes. When I got to Hazel and as an employee in 1996, I was hired as a public policy analyst, we had a singular focus in terms of advocacy. It was around smashing stigma and promoting access to care. The target we had was private health insurance. Up until 2008, not that long ago, until 2008, insurance companies could discriminate against people with substance use disorders or mental illness or both. That's wrong. That's wrong, especially since substance use and mental illness are at the root cause of so many of society's issues.

My focus was in getting insurance companies through a legislation in Congress to finally, in 2008, get that legislation passed Congress and get President Bush to sign it into law. Then two years later, we got addiction and mental illness covered under Obamacare, so finally, we succeeded in expanding access to care in private insurance and the public sector. Today, the law is if you struggle with a substance use issue, or have a mental health issue and you have insurance, you should be covered as you would be covered for any other chronic illness.

Alison Stewart: We got a text from Joanne from Manhattan. I'm in recovery almost seven years from heroin and crack. Narcan saved my life twice. Community keeps me going every day. Harm reduction work and volunteering is the most important thing to me. Congrats on your ongoing recovery. Let's talk to Bill from New Jersey. Hi, Bill.

Bill: Hi, Bill. I'm an alcoholic. I'm 33 years sober. I'm a Catholic priest. Tomorrow I will celebrate 43 years being a priest. If it wasn't for AA and the rehab I went to, I'd probably be dead or I definitely wouldn't be active and productive priest. I'm so glad. I was just passing by from visiting a friend in a hospital, and I heard the thing, and I said, "I got to call and share a little bit about I am so grateful to Alcoholics Anonymous and God because without them, I might be dead today."

Alison Stewart: Thank you for calling. Let's talk to Leah, who's calling in from Albuquerque, New Mexico. Hi, Leah. Thanks for calling.

Leah: Hey, y'all. I'm Leah. I'm an addict and really grateful to be clean. It's a good day to be clean. I want to thank you and your guest for the program and the share of the story so far. Congratulations on staying clean today. I just wanted to primarily share a message of hope that this is doable. I was one of those people that struggled in and out, in and out, in and out.

I am a member of the Narcotics Anonymous Fellowship. I came close to giving up, but I kept coming back, and they kept telling me that, "Where the body goes, the mind will follow," because I kept trying to figure everything out, and it doesn't require figuring it out. It's not about thinking my way through this. I'm sure your guests can relate to this. It's about what I do because I could tell you all day long what I needed to do to get clean, and stay clean. It didn't matter what I know, it's what I do.

Also, I have a resentment about the treatment facility industry because it's obscene and they've blown it up and it's not necessary. When I had an experience at a treatment center, it was a great thing. I'll shut it down here. It was a great thing. I didn't stay clean after. I was there for 90 days. I didn't stay clean after but I did learn a lot of things. The bottom line is I'm going to be told to go to 12 Step meetings to work the program to learn to live it. Don't use, work with a sponsor, work the steps, go to meetings, pray and help somebody else.

Alison Stewart: Leah, thank you so much for calling in.

William Cope Moyers: Those are very powerful testimonials. They're all true because they are the experience of the callers, your listeners. For me, who was well grounded in 12 Step recovery, for me, who is well grounded in my faith, my parents raised me to be a man of faith and I'm grateful for that, for a man who was also a public affair, all those things were important to my recovery, but there came a moment in time when I was prescribed the opiates, when all of those tools in my toolbox were not enough to get me back on track in the way that I had been recovering up to that time.

Alison Stewart: We'll talk more about that time with William Cope Moyers. If you'd like to join our conversation, are you in recovery? What's helped get you get through the day? Our number is 212-433-9692, 212-433-WNYC. You can join our conversation or text that number. We'll be right back. You are listening to All Of It on WNYC. I'm Alison Stewart. My guest is William Cope Moyers. He has written a memoir, Broken Open: What Painkillers Taught Me about Life and Recovery.

All right. You're in the dentist chair, and you underwent the gas and you had a panic attack. You recognized there was something about this feeling. What was it about the feeling of being under the gas?

William Cope Moyers: It scared me because it felt like it had separated me from my recovery. They say that addiction is in every cell in our bodies. It's an illness of the mind and the body and the spirit, so if we want to recover from it, we've got to replace what's in those cells with recovery. We've got to deal with our minds and bodies and spirits. When I breathe that gas and I never had nitrous oxide before, I wept. I wept, and I wept, I think because I was scared to be separated from the control that I had felt in all those decades over my recovery, and there's where it began.

Alison Stewart: We should say this was 2012-ish?

William Cope Moyers: About 2012, towards the end of 2012. That's right.

Alison Stewart: People didn't quite know about opiates. "Oh, take opioids. It makes you feel better. It will relieve you from your pain. That's what it was scheduled for."

William Cope Moyers: There's nothing wrong with suffering with pain. Listen, we're a species that does not like pain, and the fifth vital sign became pain, and with it became this incredible marketing effort by the pharmaceutical companies. Hindsight being what it is, I should have been more wary of what that meant, but I never liked opiates. I was a crack addict and an alcoholic, and I was suffering with pain, which became chronic pain in my jaw. I took those opiates, and I liked them. Why did I like them? Because I didn't hurt. but also they took the edge. They took the edge, Alison, off of my life.

I was a fast runner through life. I'm a perfectionist. I was a busy parent and all those other things. At least for a couple of hours when I would take the pain meds, they made me feel less on edge and more at ease.

Alison Stewart: Your language around your dependence on opiates was interesting. You would say, "I had a run in with opiates," that you tell people, people you felt comfortable with. Why did you use that language? "I had a run in with opioids."

William Cope Moyers: Because the alternate would be to say I had a relapse. The term relapse in our field, particularly in the recovery aspect of the journey, is a shaming term. We don't use that term to really describe a recurrence of use or recurrence of any other chronic illness. For me, I hadn't had a relapse in the way I understood it. I had always been treated for a crack addiction and a propensity to drink too much.

There I am, still sober from those substances, but struggling with pain meds. In those first public talks that I would give, I would talk about the fact that I had this run in. Why was that? Because I didn't know how to describe it, and I had, frankly, a lot of shame with the fact that I had a return to use or had had another experience with substances. I had to find the language that worked for me in describing not only my addiction, but also my ongoing recovery.

Alison Stewart: What did you do to get opioids, opiates?

William Cope Moyers: I kept going to the dentist because I did have a lot of procedures during that period of time. I did develop a neurology in my jaw, but here's the thing, the medical profession, the dental profession, they're often as ignorant about substances as any other profession is and they're the ones that have been doling them out. It's why we developed an opioid epidemic in this country.

At Hazel and Betty Ford, we didn't used to see people addicted to opiates like we started to see 15 years ago and 10 years ago. I kept showing up at the dentist for the procedures I was having and probably for some procedures that I could have avoided if I had just paid attention to doing my physical therapy and so on. Because these dentists, for the most part, knew who I was, knew where I came from, and trusted that what they saw was the truth, they continued to prescribe them for me.

Alison Stewart: You were busted by a longtime doctor, who just presented you with the evidence. What did you think when he presented you with the evidence of how many pills you had been taking?

William Cope Moyers: It shook me. It shook me and yet it affirmed at the same time that I had an issue that I could not deny and I needed to do something about it. The interesting aspect of that was he couldn't help me either, and he had been my long term internist, who ironically, was a man in long term recovery himself. He knew I needed something else beyond all the things that I'd had before and beyond all the things that had worked for me in the past, so he, "Busted me," but what he really did, Alison, was just tell me the truth.

Alison Stewart: Let's take a call. Seth, thank you so much for calling. Seth is calling from-- I'm not sure where you are, but hi, Seth.

Seth: I'm in Brooklyn. How are you doing?

Alison Stewart: Doing okay.

Seth: Bill, congratulations on your, on your, on your recovery. I was a crystal meth addict for about 25 years. I want to say that the struggle that I had to get into rehab was enormous. They didn't regard crystal meth as seriously as they regarded opioids. Everything has a hierarchy about how you get into rehab in this maybe the state or the country. There's very few resources for people when they're addicted to different things.

I want to know your comment about that. I had to lie to get into detox to get over crystal meth addiction. It's been two years for me, and I'm very proud of myself, and I'm very proud of the people who I worked with to do this, but it took a lot of hard work, but I had to finagle my way into rehab.

William Cope Moyers: Good for you. I'm proud of you for finagling your way into rehab. You're doing it, you're doing it a day at a time, but you're right. Addiction is a chronic illness. It's one that is pervasive. I've always talked about the fact that addiction does not discriminate and neither should recovery, but recovery does. Not enough people who struggle with this illness can find access to care, can find access to recovery support.

At Hazel and Betty Ford, we treat 25,000 people a year. We've been doing that since 1949 and that's just a drop in the bucket. There are not enough resources. That's why this conversation is all about raising awareness about the fact that we need more when it comes to resources to treat people like us.

Alison Stewart: Got a text. In recovery for two years. Drank myself to death and received a life-saving liver transplant at 33. Opened a non-alcoholic bar in Philadelphia and continued to provide a safe space for those looking for the social benefits of a third space in combating loneliness as well as substance abuse. Listening right now and I want to give both a big thank you for all these wonderful words of hope. My daughter is in rehab right now and it's been rough for all of us. I'm so grateful for all the ways that my daughter is trying to break free from this horrible grip of addiction. To deal with painkillers, Bill, you chose to take Suboxone.

William Cope Moyers: Yes.

Alison Stewart: Did you have an opinion about Suboxone before you took it?

William Cope Moyers: I thought it was for people who had an opiate addiction. [chuckles] I thought it was an important tool. We started using it at Hazel and Betty Ford in about 2011 because we were not having success in treating our opioid dependent patients. I thought it would be for other people. For me, it was a magic bullet. The magic bullet in the sense of it quieted my craving brain and allowed me to pick up all those other tools that I had been using so effectively in recovery for decades and start using them again.

My opinion is an FDA approved medication that can quiet the craving brain and help people get on their path to recovery is a good thing. Thank goodness for Suboxone because I'm not sure that I could have made it without that tool as well.

Alison Stewart: You wanted to tell everyone that you were on Suboxone, you were very excited about it, you were getting ready to give a speech, you were going to mention it and it was considered controversial, and so much so, the live stream of the speech got pulled. Could you explain the controversy?

William Cope Moyers: The controversy is that it's an opiate. It's an opiate that has a ceiling so that it doesn't get you high, if that's how you want to describe it, but it's an opiate that's good enough to quiet the craving brain. A lot of people, particularly in 12 Step recovery, think it's cheating or that it's a crutch. By the way, a lot of these people are the ones who use nicotine, by the way, to maintain their recoveries.

There's a controversy around it. There's also a controversy over the fact that a lot of doctors won't prescribe it and so it's not available to people who need. That's why my journey of recovery also is one that includes telling the real story. For me, Suboxone has been an asset that has allowed me to walk my walk a day at a time for a long time now.

Alison Stewart: Would you have had that opinion say 30 years ago?

William Cope Moyers: I probably wouldn't have given it any thought, to be honest with you, Alison. Science and medicine have come a long way in the treatment of addiction. That's why I think what ultimately is the important message here, which is recovery is a journey. It's not a destination. No two of us are going to do it the same. Even the people who've been calling in and texting in today, we're all doing it differently. The key is to treat people like us with dignity and respect and to recognize that again, this journey is unique to each of us. The aspiration should be to be a better person, to walk our walk, never perfectly, imperfectly, of course, but to never give up.

Alison Stewart: I think we can have time for Steve to talk to us. Hi Steve, thanks so much for calling.

Steve: Hi there, Alison. Thanks so much to be hearing you again consistently on the radio. I am a grateful father of a son in recovery and he has been in recovery a few years now after the most treacherous, frightening period of my entire life. The parent experience, the family experience is treacherous in all ways. There are so few who are out there with solid information to guide us. There's shame and blame associated with being a parent.

Some of us in the New York, New Jersey, Connecticut area get together and we have support group, a parent support group that helps. Nothing else has helped me keep my equilibrium while I've turned my son over to professionals. We even have a podcast we call My Child and Addiction. It's a free non-commercial podcast where we just share hope, support, and love because families need all the help they can coping with the sickness of their kids. It is a scary unlike any other experience most of us feel, so I thank you. I thank you for raising the level. We can't whisper about this anymore.

Alison Stewart: Thank you so much for calling, Steve.

William Cope Moyers: As he just said, addiction is a family illness and we at Hazel and Betty Ford know that recovery needs to be a family process as well. Even for the addict and the alcoholic who does not make it, the family must continue to work on themselves so that they can recover as well too.

Alison Stewart: This is a great text to end on. "When stressed, I tell myself it's one day at a time. Tomorrow is a promise, but since in theory tomorrow may never come, all that I have to do is focus on today."

William Cope Moyers: Amen.

Alison Stewart: The name of the book is Broken Open: What Painkillers Taught Me about Life and Recovery. It's by William Cope Moyers. Thank you so much for coming into the studio. We really appreciate it.

William Cope Moyers: Thanks for having me today, Alison.