Why Artist Ben Shahn Embraced Nonconformity

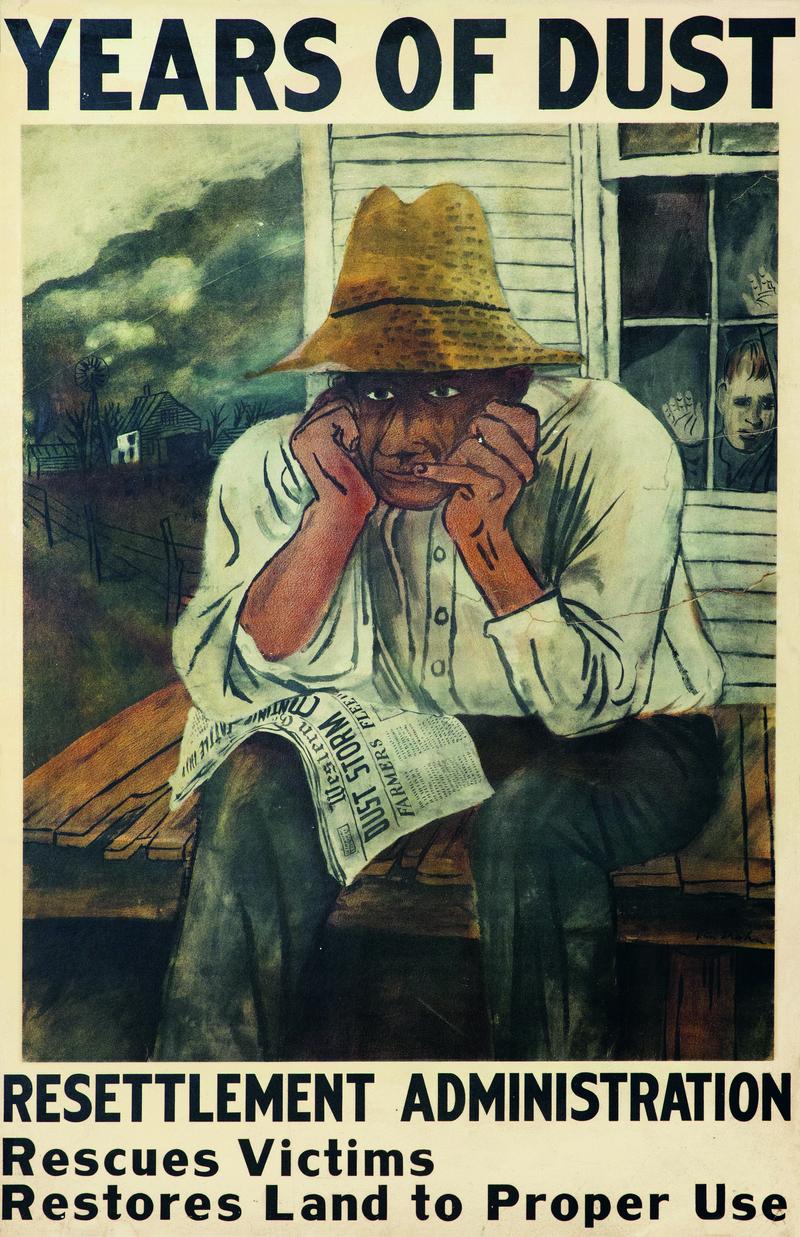

( Painting by Ben Shahn )

Tiffany Hansen: This is All Of It. I'm Tiffany Hansen, in for Alison Stewart. For the first time in nearly 50 years, you can see a retrospective of a New York hometown artist who maintained his singular voice even when it wasn't always easy to do so. The artist is Ben Shahn, and the Jewish Museum has organized a new exhibition of his work, which spans multiple decades and features 175 pieces. The show examines Shahn's social realist paintings, how he advocated for his progressive views with his art, never compromising to the times.

Shahn was Jewish. He immigrated to New York from the Russian Empire as a boy and grew up in Williamsburg. He dedicated himself to being an artist, always within the framework of what he called non-conformity. The show at the Jewish Museum is fittingly called Ben Shahn on Non-Conformity. It's on view now through October 12th. You can see a sample of the work from the show on our Instagram story @Allofitwnyc. With us now is guest curator and James Madison University art history professor, Dr. Laura Katzman. Hi, Dr. Katzman.

Dr. Laura Katzman: Hello. Welcome [crosstalk]

Tiffany Hansen: Great. Also, Jewish museum curator, Dr. Stephen Brown. Hello, Dr. Brown.

Dr. Stephen Brown: Thank you, Tiffany. Great to be here.

Tiffany Hansen: Let's start by talking about that word non-conformity. I'm curious, Dr. Katzman, what did Ben Shahn mean by non-conformity? How is that different from what other people might imagine when they hear the word non-conformity?

Dr. Laura Katzman: Well, thank you for that question. Non-conformity was a very good umbrella term to call the show because it came from Shahn's own words. This was an essay that he wrote in 1957 called On Non-Conformity, which came out of his Charles Eliot Norton lectures at Harvard University. It's important to note that he formulated these concepts in the Cold War in the 1950s, when he was under political pressure. I guess you could say in the McCarthy era, being questioned for his liberal views, as well as dealing with the rise of abstract painting and the rise of abstract expressionism, and followed by conceptual art forms that became all the rage in the 1950s. Especially by the late 1950s.

That gives you some context for some of these ideas. Shahn believed that this was his credo. His credo, his political and artistic credo for freedom of expression. For him, the artist is the non-conformist. The artist is an inherent non-conformist who had to speak their truth, had to go against the grain, however unpopular, had to go against Faddish trends had to be courageous. That was the only way to create great art and to move society forward. This became a great umbrella concept for the exhibition, which we hope advocates for Shahn being one of the most influential and consequential socially engaged artists in the United States in the 20th Century.

Tiffany Hansen: Out of curiosity, are there other artists that you would put under that non-conformist umbrella?

Dr. Laura Katzman: Well, it's a hard question to answer. One could say that the abstract expressionists who emerged in the 1950s might have seen themselves as non-conformists. I think the term is going against the grain. It's going against the grain. If abstract artists felt that they were going against the grain of figurative realism, then they could see themselves as non-conformists. I think that it's a term that is- how should I say it? It's broad enough to encompass many points of view.

Tiffany Hansen: Right. Non-conformity is in the eye of the beholder?

Dr. Laura Katzman: In many ways, that's right. Also, I think it's important to link it to absolutism. Shahn was indignant about absolutism, indignant that it was a danger to society. That is one point of view. One point of view, whether it be one way, one direction in art, in politics, and philosophy. He was a First Amendment guy in the sense that it was more freedom of expression, the better. He railed against abstraction because he did not think that it was connected to the human prospect, as he said. He certainly didn't want to shut it down.

He certainly believed that all artists had the right to express themselves in the way that they felt best. In fact, he engaged deeply with abstract artists in the 1950s and symposia conferences, and wanted to have a debate about the direction of American art. He was a free thinker in that regard.

Tiffany Hansen: I would assume that by the very definition of the word non-conformity, there is no visual cue to us as enjoyers, lookers, onlookers of artists and art. There is no visual cue that we need to be looking for, is there? Is there something writ large about non-conformity? It does take so many forms. Is there something that you can point to in Shahn's work that is a visual cue to his non-conformity?

Dr. Laura Katzman: That's complicated to answer because he had such a diverse evolution from this very documentary style based on photography, very indebted to photography in his early years, when he was speaking out against injustice. Then, a more universalizing style emerged in the allegorical style emerged in the post-war period. Then, he moves to a more lyrical, spiritual style in his late work. All the while, social justice is threaded throughout. I would say that there's no one clue or key. I think it's the freedom to express oneself not only in your own style, but also to move freely between media.

I think there's a seamless comfort that Shahn had moving from painting to murals, to photography, to commercial work, to book design. It was quite extraordinary, the breadth and depth of his range and of styles. I suppose artists can feel confined to one style, to one type of work. He broke down the hierarchy between so-called fine art and commercial art, which was considered lowbrow art. He was an image-maker. He was an image-maker and he believed in the power of the image to communicate, no matter what media that was.

Tiffany Hansen: Dr. Brown, I want to talk a little bit about that early life, about Shahn's early life. Give us a little history. I mentioned a little bit of it in the intro. He was born in 1898 in what is now present-day Lithuania. It was then the Russian Empire. He moved to Williamsburg. What do we know about his early life there, and what Williamsburg was like at that point, and how it was a fertile ground for someone like him?

Dr. Stephen Brown: The impression I have from the data is that the life of the immigrant that Shahn shared with thousands of other immigrants was very hard and economically challenged at the time, with tremendous senses of community and a search for a purpose in America. There's one beautiful painting in the show. It's a visionary work. It's related to muralism with which Shahn became associated as a major public artist. That picture is a vision based on a mural that he was going to make for the Jersey Homesteads, which was the place in New Jersey where the immigrant population eventually were going to be placed away from the squalor of the Lower East Side.

I think, in that painting, you can feel that Shahn knows every single coordinate of that immigrant experience. From the pogroms of the Russian Empire, all the way through to the Seders on the Lower East Side, all the way through to, hopefully, the utopia of a new beginning in the new world. Yes, I would say, almost, in a way, it's written throughout the show that this is an immigrant story. Of course, because of that, it speaks on a global level to one of the most important discourses of our time, which is global migration. Not just in America, but all over the world. I think that resonance will be felt and is being felt by many people who visit the show.

Dr. Laura Katzman: May I weigh in on that on Williamsburg?

Tiffany Hansen: Of course.

Dr. Laura Katzman: I wanted to enhance what Stephen was saying. It was a teeming neighborhood of, or location for, working-class immigrants of Shahn's background. He grew up with a great deal of socialist feeling, socialist mindset. His father was a socialist in Russian-controlled Lithuania. His father was an anti-czarist activist who was banished to Siberia, made his way to South Africa, and then eventually to the United States. I like to say that his social justice inclinations were in his DNA, and then they were reinforced certainly by the working-class immigrant environments that he grew up in, because they were very pro-labor union. He was taken out of school at age 14, 15 to support the family, and he was apprenticed to a commercial lithography workshop.

Tiffany Hansen: You dovetailed right into my next question perfectly, thank you. Describe for people who don't know what lithography is, and then talk about his training there.

Dr. Laura Katzman: Lithography is an art form that at that time involved almost engraving into stones. Shahn was given this rigorous, disciplined training as a lithographer, a journeyman lithographer. He was responsible for commercial posters, billboards, that thing. Also at that time, the lithographer had an extraordinary training in typography and letters. Type. This served him very well for the rest of his career. He was very angry that his family took him out of school because he wanted to study. He did study in the evening and eventually got his high school diploma.

This set the stage for him as an artist who could engage in the commercial world, who could embrace lettering and language at an early age, who developed a very strong, potent line that carries throughout his work. As Stephen Brown and I have talked about, again, the discipline of this training served him very, very well.

Tiffany Hansen: Yes, Dr. Brown, I want to get to- You mentioned the impact of his immigrant community and what that had on him as a person and on his art as well. One of the other moments in history that had a great impact on him was the Great Depression. Describe that for us. What impact that had on him.

Dr. Stephen Brown: I think Shahn was-- If you go through this exhibition, it's very important to see the various phases of Shahn's career and art. In fact, the Depression as such is not titled or named. It's not a section in the show. It begins with his involvement in photography and his work, moving out of his own interests, working alongside his great friend Walker Evans, with photography, to back up a little bit. This was his way into the image-making as a public artist that he wanted to do. It jived perfectly with Roy Stryker's brief.

To document the South in America, which was suffering from all the horrors of the Dust Bowl, and what was happening to the agricultural communities across America. That dovetailed perfectly because Shahn was sent to document those workers. He was dragged-- Not only did he experience depression, with all of its poverty and difficulties, personally, but he was thrown into the position of experiencing it through the lives of many Americans.

Tiffany Hansen: We will see some of these photographs in the exhibit.

Dr. Stephen Brown: Laura has done a great deal of work, and we're indebted to all of the tremendous research and previous publications. We do have an opportunity in this show. I'm rather surprised about it because it's a lot of data to compress into a relatively small gallery space. We've got both his work in New York, photographing the populations at street level in a very gritty, realist way. We also have, against that, some of the documentation from the Farm Security Administration he worked for. It's an amazing segue into the next section of the exhibition, where that investment in photography and, as it were, the quintessential or realist art par excellence of the 20th century, then becomes moved into posters and murals. You do see, both for art lovers and the general public, but particularly for artists, how the artist's process and his way of going about making his imagery.

Dr. Laura Katzman: If I can add to that, the idea of the great context of the Great Depression is absolutely central to Shahn's work. He was artistically on fire in the Great Depression. His response to it, through photographs, as Stephen said, posters, working for the government. First, working on his own and then working for the government. Like many artists on the left, able to embrace the New Deal. The idea of artists being hired in the middle of the Great Depression, in the middle of an economic crisis, to respond to what was going on in society was very motivating for him and stuck with him the rest of his life.

He advocated for government support of the arts for the rest of his life. It was an extraordinary time for him to also see the dire poverty that was going on in the United States and to document it, which he then used. The government used it to bring relief to people, to speak to the New Deal programs, but also to justify the funding that was going to help farmers. Also, as a body of work that he was building, that he was going to draw on the rest of his life. It was photography that brought an authenticity to his work. He had seen these people with his own eyes.

He had encountered them and engaged with them. He didn't feel he could paint or document there. Their situations without having that direct contact. Photography was absolutely critical for him. The New Deal section establishes that.

Tiffany Hansen: We'll have to leave it there. We'll see the evolution of this artist, Ben Shahn, at the Jewish Museum. It's on display through October. Thanks so much to our guests. Dr. Laura Katzman, Dr. Stephen Brown, we appreciate your time today.

Dr. Stephen Brown: Thank you so much.

Dr. Laura Katzman: Thanks.