What New York Looked Like in 1776

Allison Stewart: You're listening to WNYC. I'm Allison Stewart. It's time to announce the choice for our book club, Get Lit with All Of It. Our selection for January 2026 is The Emperor of Gladness by Ocean Vuong. The story follows a struggling young man who becomes the caretaker for an elderly woman who struggles with dementia but has wisdom to spare. For work, he finds a job at a fast casual place full of coworkers with different hopes and dreams. Ocean Vuong will be with us for an event on January 20th at 6:00 PM at the NYPL, the Stavros Niarchos branch at 40th and Fifth Avenue. For tickets, they are free, but they're first-come, first-served. Go to our website, wnyc.org/getlit.

New Yorkers, you can get an e-copy of the book from our partners at the NYPL, or you can pick it up at your local bookshop. That's Ocean Vuong, The Emperor of Gladness, our choice for Get Lit with All Of It book club this month. That's in the future. Let's get this hour started with a look to the past, 250 years to be exact.

[MUSIC - Hannibal Hayes: All Of It Theme Song]

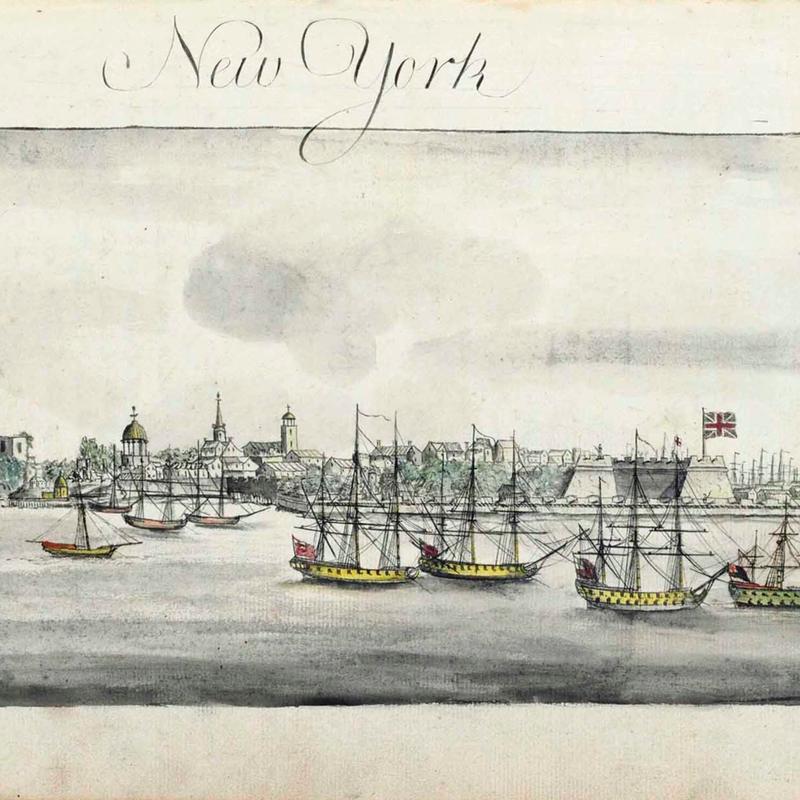

Today is our first full show of 2026, and 2026 is a big year for the United States. Do some quick math, and you realize that this year is the country's 250th signing of the Declaration of Independence. Now, there are a lot of different opinions and agendas about American history these days, how we should mark the semiquincentennial and what the revolution means to modern-day America. We'll be covering America's 250th birthday in our own way this year and in all of its contradictions. We're going to kick off our coverage today by traveling back to 1776 New York to learn more to the extent about the way the revolutionary fever had swept up in the city, who was here, what the city looked like.

We have some help now, courtesy of the Fraunces Tavern Museum at 54 Pearl Street. The tavern was standing during the revolution. Melissa Lauer is the museum's Manager of Education and Public Programs, and she joins me now in studio. Hi, Melissa.

Melissa Lauer: Hi. Thank you.

Allison Stewart: When we say New York, 1776, what do we actually mean? What were the city limits?

Melissa Lauer: Very, very different and much smaller. If you're imagining actual New York City 1776, that's going to be the tip of the island of Manhattan, only up to right around where City Hall Park is today, so-

Allison Stewart: Wow.

Melissa Lauer: -you've got a city of about 25,000 people, second biggest city in the colonies at the time, crammed into just about a square mile of space.

Allison Stewart: There were Indigenous people on this island by 1776. How much of an Indigenous presence was there in Manhattan, in the New York region?

Melissa Lauer: New York region is much more significant than right in our area in New York City. This is a space that has been occupied by colonists for a long time by the outbreak of revolution. While the Indigenous presence is absolutely still felt in and around the city, it's going to be much more present and active once you start moving outside. Once you start getting to what is still a frontier around outer New York. The Haudenosaunee, the Iroquois Confederacy, they will play really a very large role in the revolution, but that's going to come just a little bit later. As things keep developing right now, they're going to be more trade partners.

We're still coming off the Seven Years' War, the French and Indian War, so there's absolutely influence, but it's not necessarily as much in the streets of New York City as it maybe was even 30, 40, 50 years before.

Allison Stewart: All right. The streets of New York City, that mile you just described, what's it like on an average day? What are we experiencing?

Melissa Lauer: It is a busy, bustling city. This is a port city. It's huge for the time, and it's very diverse. You're going to be seeing people from all over. You're seeing merchants, seamen. You're going to be seeing traders all the way up to elites. We still have a landed gentry class that are in and around New York City, too. You've got the lawyers, the printers, the tavern keepers. It's people from all walks of life figuring out how to live together and build something that's already unique in the colonies.

Allison Stewart: Listeners, we want to hear from you. How are you planning to reflect on the 250th anniversary of the US this year? What do you want to know more about New York during the Revolution? Is there a piece of New York revolutionary history that interests you the most, and why do the ideas of revolution still matter? That's the essay question. Our number is 212-433-9692. 212-433-WNYC. My guest is Melissa Lauer, Manager of Education and Public Programs at the Fraunces Tavern Museum. At this time, you said it was a major city. Philadelphia was a little more of a political center of the colonies at the time, so what was New York's reputation in the colonies in 1776?

Melissa Lauer: One of the important things to think about when you think about New York City is its place geographically. Because not only is it a port city, but it's located right in between the other two largest cities of the time, which is Philadelphia and then Boston up north. People are used to traveling through New York on business and for leisure. It is an active crossroads. Even people traveling down to Congress, political meetings down in Philadelphia, are often going to be passing through and stopping and staying in New York City in between. It's known for exactly what it is. It's known for its commerce and its diversity and its rudeness and its New York character.

Allison Stewart: Tell me more about its rudeness.

Melissa Lauer: John Adams, he actually writes when he's passing through New York to one of these meetings in Philadelphia that the people of New York speak, I think the quote is, "very loud, very fast, and altogether." It's exactly the character that you think of today. There's this reputation that New Yorkers have very early on because that's what New York City is. It's this place where all these different people are coming together and trading and living and building this life.

Allison Stewart: Somebody just texted me, "So nothing's changed," basically.

Melissa Lauer: There you go.

[laughs]

Allison Stewart: At the beginning of 1776, how strong was the British presence in New York?

Melissa Lauer: Not very strong at all at the very beginning. If we're looking right around this time, 250 years ago in January, the city is under de facto Patriot control. The British governor, William Tryon, has been pushed out of the city in the fall of 1775. Most of the British forces are still stuck in Boston, which is under siege by the Continental Army and its brand-new commander, George Washington. That's the focus, and New York is not yet going to be the main stage. It is in January of that year that Washington will order the city to begin preparing for what he expects to be a British invasion later in the year. They know it's coming, it just hasn't started yet.

Allison Stewart: Somebody just texted what my next question was. The question is, "Thoughts on Black votes in New York City in 1776?" We know that New York would not abolish slavery until 50 years later, in 1827. What role did enslaved people play in New York?

Melissa Lauer: A very, very integral one. This again, it's a city of trade and commerce, and that absolutely includes the slave trade. New York City is a part of that. If you again start looking a little bit out of the city, you do have some large estates with large enslaved populations. In the city, that's a reality as well. Likely, you couldn't walk down one of those streets in this square mile of city without passing a household where there's at least one person who's enslaved there. They're here, they're a massive part of building the city as it's come to be by 1776. As the war gets started, that's going to start shaping everybody's lives.

At this point in the year, early 1776, people will have started to hear about Lord Dunmore's proclamation, which is actually coming out of Virginia, not New York, but he is the British governor of Virginia. State is now embattled. He puts out this proclamation that states any enslaved person who's able to get away and fight as a Loyalist will be guaranteed their freedom. Those ripples are going to spread through different communication channels, and people are going to start thinking about, "What does this war mean for me? Which side do I choose?"

Allison Stewart: Northern cities did have free Black populations, though.

Melissa Lauer: Absolutely.

Allison Stewart: How prevalent was the free Black population in revolutionary New York?

Melissa Lauer: It was definitely present. It's going to become much larger following the war years than it even is at the beginning. That's in part because of some of these proclamations, some of the migration that's going to happen over the course of the war. It goes all the way back to the beginnings of New York City that you'll have both enslaved and free Black populations active living building community in the city.

Allison Stewart: Let's take a couple of calls. Let's talk to Carmelo in Hackensack, New Jersey. Hi, Carmelo. Thank you for taking the time to call All Of It.

Carmelo: Thank you very much, Allison. Happy New Year to one and all. I just want to say that I grew up in Hackensack. As a kid, we used to see all the retreat routes that George Washington took, and we used to go to the Fort Lee Historic Park and overview Manhattan. We used to imagine what was happening during the revolution, how this country was shaped. It was just such a learning experience. I grew up around the corner from a Revolutionary War cemetery, which still today is there. It's on Hudson Street in Hackensack. It's just remarkable to see and hear the conversation of how we reshaped and how we were such an integral part of this country.

To me, it's just so rewarding to still see and hear these things, and so happy to be around for our 250 anniversary. I think it's just something that you see, but you don't quite get a grasp of it until you can imagine when we have something like our anniversary of our country coming up. It's just fabulous. I wanted to say thank you for having me on.

Allison Stewart: Thank you so much for calling in. Let's talk to Francie in Manhattan. Hi, Francie, thanks so much for calling.

Francie: Hey, hi, Allison.

Allison Stewart: Hello?

Francie: Allison, it's such a fabulous synchronicity that this coming Saturday, January 10th, 2026, is the 250th anniversary of the exact date that Thomas Paine released to the world Common Sense, which of course changed the trajectory of the world and certainly the United States. There's going to be a staged reading by attorneys in where else, what better place, Fraunces Tavern in the Flag Room, on Saturday, January 10th, at 12:30 to 1:30, and everyone is invited. There is no fee, but you must reserve on the Fraunces Tavern website in order to have a place at the table, so to speak.

Allison Stewart: Thank you so much for calling in. We're going to discuss that on the show on Friday. Let's talk about Fraunces Tavern, Melissa, Manager of Education and Public Programs at the Fraunces Tavern Museum.

Melissa Lauer: Absolutely.

Allison Stewart: What was the original story of Fraunces Tavern?

Melissa Lauer: It goes very, very far back. It was originally built in 1719 as a house for Stephen Delancey, who's going to be one of the prominent families all the way up through the American Revolution beyond. It became a tavern when Samuel Fraunces purchased that building in 1762, which is right as we're starting to build up some of this resistance that will come about because of the British Acts, the taxes that are going to come through, and some of the resistance to that will really be born in Fraunces Tavern.

It was a revolutionary meeting place, which epitomizes some of the conflict that you'd see even in a space like New York City between Loyalist and Patriot beliefs that are going to be building up in here.

Allison Stewart: I was going to ask you, because eight months prior to 1776, and April of 1775, that was the Battle of Lexington and Concord. How much revolutionary spirit was there in New York compared to Boston?

Melissa Lauer: Every colony is different. Boston has that reputation for a reason, of being the seat of revolution, but it doesn't end there. You can't really label a colony as purely Patriot or purely Loyalist. They really are going to be real ideological struggles that are happening everywhere. That means that that is present in New York. There's a group of Sons of Liberty who are meeting at Fraunces Tavern, having some of these conversations. They hear about the Boston Tea Party. They decide to have their own version in New York to protest the Tea Acts. It's happening all over.

There's these very loud, sometimes violent groups in support of the Patriot cause, and you also have Loyalists. It's a Merchant City. There are people with a lot of ties to Britain with their livelihood, their family's backgrounds. They're afraid of letting that slip away. There's a lot of people who are caught somewhere in the middle where they don't know what the right choice is going to be. There's a lot of chaos involved with this idea of democracy. At the same time, you've got these boycotts. You've got this popular spirit. Thanks to our caller who just came in, Common Sense is about to come out in January of 1776.

That does have a massive impact on public opinion, starting to bring the common language to these ideas that gives people something to rally around and starts to solidify some of that support, including in places like New York City.

Allison Stewart: This year, the United States is commemorating its 250th birthday. To kick off our coverage of the anniversary, we're discussing what one would see and experience in New York as 1776 began. My guest is Melissa Lauer, Manager of Education and Public Programs at the Fraunces Tavern Museum. We'd also like to hear from you. How are you planning to reflect on the anniversary this year? What do the ideals of the revolution-- Do they still matter? What do you want to know more about Revolutionary New York? Our phone number is 212-433-9692. 212-433-WNYC.

We got a text that says, "What did New Yorkers do for leisure or recreation? Did people even have activities at that time?"

Melissa Lauer: Oh, absolutely. That brings me right back to taverns. They are a seat of social life, in part because they offer exactly that. They offer opportunities for leisure. People aren't necessarily going to be spending as much time at home as you would associate with today. You're not necessarily inviting people over for a game night, for a dinner at your house, unless you're a lot wealthier. Taverns are the spaces where people come together for a little bit of fun, whether that's a drink and a meal or whether it's a dance. Samuel Fraunces could have cleared out the Long Room in Fraunces Tavern, the largest room in the building, moved out that furniture, and held scientific lectures, dance programs, opportunities for people to socialize, and experience the world.

This was happening all over in taverns that could offer different, little interesting activities. There's a story that you could go to a different tavern in the city and see a real live jaguar. Things are coming from all-

Allison Stewart: Wow.

Melissa Lauer: -over to New York City, and people are just as interested in all of it as they would be today.

Allison Stewart: Let's talk to Shane from Westfield, New Jersey. I think he has a question. Hi, Shane.

Shane: Hi, Allison. Thank you to Melissa for this very interesting segment. In my learning more about the revolution, it surprised me and was very much different from what I learned in school way back when, that as Melissa said a couple of minutes, there was real divided opinion among the general population as to whether or not to support the revolution. That certainly was at this time, but it really continued throughout the war. Unfortunately, that resulted in a lot of violence between those civilians who were supportive of the cause and those Loyalists who were unsure because they really were English by origin.

That violence was something that I think it becoming a real civil war that many of us didn't appreciate.

Allison Stewart: Thank you for your question and your comment, Shane. The idea of what a war means is something to be taken seriously.

Melissa Lauer: Absolutely. Calling it a civil war, I think, is absolutely accurate. It is a rebellion, but it's between people who, a year ago, all considered themselves loyal British citizens when the war gets started. There's not this huge rallying cry for independence. People don't want to break away from Great Britain as much as they want to have that representation part of "no taxation without representation." They want their rights as British citizens in the way that they envision that. It takes a lot of this violence, this political violence, in some of the early battles of the war to start changing people's minds. They have to see British soldiers burning a town.

They have to see some of these abuses actually happening on their soil before people who maybe have less of these calculating political minds are going to get on board with what this is really going to mean for them.

Allison Stewart: Let's talk to Charles from the Upper West Side. He has a question for you. Hi, Charles. Thanks for calling All Of It.

Charles: Thank you so much. I feel like an idiot asking this, but was Fraunces an African American?

Allison Stewart: Fraunces Tavern?

Charles: Yes.

Allison Stewart: Have you heard that?

Charles: I always wanted to know his history.

Melissa Lauer: Yes. There's a lot that we don't know or don't know for sure when it comes to Samuel Fraunces. We know, I believe, from his census record that he was recorded as white in one of the censuses, but there are stories going pretty far back that cast some doubt on what his race may have been. It's likely that we'll never be able to say for certain. It depends which sources are you going to pull from. Do you go by his nickname, Black Sam? What could that have meant? It's still an ongoing question, but I think that there's a lot of fertile ground in embracing some of those questions.

What are the reasons that race might have played a role in somebody's life? Why would you pick one designation over another? At this point, I can't say for certain.

Allison Stewart: A question for you. A lot of us think we know American history because we watched Hamilton eight million times. I'm convinced there is a generation who knows more about the Revolutionary War than would have known-

Melissa Lauer: Absolutely.

Allison Stewart: -25 years ago. Who are some of the major figures in New York in 1776?

Melissa Lauer: We've got a whole cast of characters, Alexander Hamilton himself.

Allison Stewart: There you go.

Melissa Lauer: He's here. He's starting to get involved in the war. He's part of an artillery company. By this time in the war, he's starting to get involved in some of these skirmishes, and he's building a lot of relationships because, of course, he does that pretty well. He wants to use that ambition to start building a career for himself. One of those people that he gets to know is John Jay, who's another famous New Yorker. He's going to keep playing a role throughout the war. You've got your leaders of the Sons of Liberty here that we maybe don't know as well. That's going to be Isaac Sears and Alexander McDougall, who are involved in some of the rabble-rousing that's going to add fire to the cause.

Then they'll also be involved in actually fighting the war as it gets started. Then you pivot, and you look at some of the Loyalists that we know about. There are plenty of British officers still in and around the city, merchants that work very closely with them. That's a lot of those landed, wealthier, more elite families like the Delanceys, the Philipses of Philipsburg Manor, who are going to be pulling from other viewpoints and other sides.

Allison Stewart: This text says, "Green-Wood Cemetery in Brooklyn is also a great site to visit. One of the largest battles of the Revolutionary War, known as the Battle of Brooklyn. Battle Hill is known as the highest point in Brooklyn, and it's commemorated with a Minerva, goddess of wisdom and war." What's going on in the other boroughs, what we call now the other boroughs?

Melissa Lauer: Very, very different from New York City proper. The further out you go from this little chunk of the island, the more rural things get. That goes for Brooklyn, too. You're seeing a lot of rolling farmland, and that's going to be the same as you look toward the other outer boroughs, but everybody still knows what's going on. Everybody by 1776 is going to be feeling the concern. Maybe your daily life hasn't changed that much if you're a farmer way out on Long Island. Maybe these British taxes aren't having a big impact on your daily life, but you are starting to realize that this is going to have some kind of impact.

There's going to be pressure to start making some declarations about where you stand. When the war really comes to New York in that coming summer, these people are going to have a lot to contend with.

Allison Stewart: What's going to happen at Fraunces Tavern this year? Give us a rundown if you can.

Melissa Lauer: So so much. Starting now, anytime that you visit, we've got our special exhibitions commemorating the 250th anniversary. It's called Path to Liberty. It spans three galleries throughout the museum right now. We are telling the story of the revolution. It's going to keep evolving and changing. If you went today, you'd see something different than if you came back at the end of April when we're switching out some of the exhibition. We're also trying to really highlight and tease out the stories of New York and New Yorkers throughout that war as well.

Whether that's our own Samuel Fraunces or Joshua Webster, whose pistol is in the show, we can tell you a little bit about his life as an officer as he's fighting this war. We've got those exhibitions that are absolutely worth the look. We've got free tours happening every weekend. Guided tours you can schedule with me, actually. I do all of that. Then we've got our Liberty 250 series, so that's lectures, events, programming that is going to be tied into these anniversaries and these events all throughout the year.

Allison Stewart: Melissa Lauer is Manager of Education and Public Programs for the Fraunces Tavern Museum. Thank you for joining us.

Melissa Lauer: Thank you so much for having me.