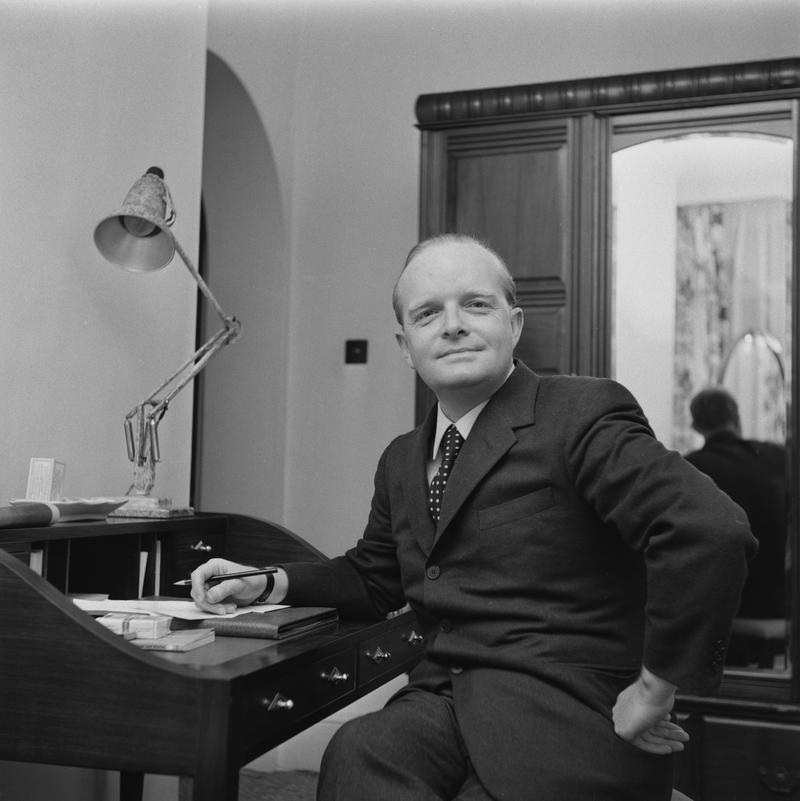

Truman Capote Turns 100

( Photo by Evening Standard/Hulton Archive/Getty Images )

[MUSIC]

Alison Stewart: This is All Of It on WNYC. I'm Alison Stewart. It's Wednesday, so we're in the middle of a book week here on All Of It. Earlier this week, we talked about NPR's list of the best books of 2024. Tomorrow, we'll hear from author Percival Everett about his great book James, which just won the National Book Award. And on Friday, we'll speak with author Samantha Harvey, whose book Orbital just won the Booker. Of course, tonight is our Get Lit With All Of It book club event at the NYPL with Taffy Brodesser-Akner, author of Long Island Compromise and special guest musical Suzanne Vega. It's sold out, but you can sign up for the livestream at wnyc.org/getlit. Now we'll keep this book week going with a conversation about one of the 20th century's most influential writers.

This year marks the 100th anniversary of the book of the birth of the author of In Cold Blood, which broke ground in the world of literary nonfiction, a bon vivant who embedded himself with our crowd of New York society, and a man whose unmistakable voice and quick wit were hard to match. I'm talking, of course, about Truman Capote.

Capote was born in 1924 in New Orleans and raised in Alabama, New York and Connecticut. Capote was a writer and a social climber. He was gay at a time when it was risky for queer people to be themselves in public. He also struggled with addiction, dying just shy of 60th birthday as the result of longtime abuse of drugs and alcohol.

Tomorrow night, the 92nd Street Y will honor Capote, who debuted In Cold Blood on stage at the Y in 1964. The event will feature actors Molly Ringwald and Griffin Dunn and a conversation about Capote's legacy with author Sloan Crossley and my next guest, author Jay McInerney. Hi, Jay.

Jay McInerney: Hi.

Alison Stewart: And author John Burnham Schwartz. Nice to see you.

John Burnham Schwartz: Nice to see you.

Alison Stewart: Hey, listeners, we want to get you in on this conversation. What is your favorite work by Truman Capote? And why could a novel or a short story or maybe you met Truman Capote once or you knew him. We want to hear your Truman Capote stories. Our Phone number is 212-433-9692, 212-433-WNYC. You can call in and join us on air or you can text to that number. John, what was your first exposure with Capote?

John Burnham Schwartz: Mine was a little unusual, I would say, in that my father was his lawyer and friend and eventually founded the Capote Trust in 1994, and so I grew up ith Truman in our house all the time. It was not the better Truman, I would say. It was definitely the sadder Truman, often drunk.

Jay McInerney: I met that guy.

John Burnham Schwartz: Yeah, you met that guy. So it was the Truman I think people have seen, certainly on television and other places. But at the same time, he was a fixture in our house and my parents were great friends with him and my father, being his lawyer. was a complicated business.

Alison Stewart: Oh, gosh.

John Burnham Schwartz: There were a lot of rehab visits and many different legal issues. It was all sort of wrapped in and it became both, at times, an inspiration, but also definitely a warning letter. I ended up becoming a writer, but it was something to see about a man destroying himself essentially, over the last years. But he could be incredibly charming, too.

Alison Stewart: Jay, you've spoken about the time you met Truman Capone. What was he like when you met him?

Jay McInerney: Well, unfortunately, I met him at the very end of his life, and I met him at George Plimpton's house-

Alison Stewart: As one does.

Jay McInerney: -on East 72nd Street. Well, Plimpton's house was kind of the literary center of New York city for about 25 years. George moved back from Paris in the '50s where a lot of expatriate writers had gathered, and he kind of started this salon, and he kind of kept the party of Paris going in New York City. Truman, I think, was a frequent guest. I certainly met a lot of prominent writers there. But at the very end of his life, in early 1984, I met Truman, and he was drunk. He seemed to take quite a shine to me because he dragged me into George's office and closed the door and proceeded to give me some cocaine while he tried to feel me up.

Unfortunately, he told me that he had discovered the sort of the fountain of youth, and it was cocaine. And I thought, "I know something about cocaine, and it's not the fountain of youth."

John Burnham Schwartz: I think he died six months later.

Jay McInerney: He died about six months later, but I had already seen him on the occasional talk show and he was-- Although in the early days, in the '50s, he was certainly a dazzling talk show guest, which is why he was so often on shows like Dick Cavett. Toward the end, he was just not even trying to mask his deterioration. I think I started with the bad Truman, but on the other hand, I was deeply impressed by books like Breakfast at Tiffany's and In Cold Blood, although two more different books, I can't imagine.

Alison Stewart: When you're thinking about someone trying to capture New York at a particular time with their writing, and it's something you did as well, what do you admire about Capote and the way he captured the city in his work?

Jay McInerney: I have a very vivid sense of sort of the Upper East Side and as it was in the-- I mean, the book is actually set in the '40s, although Truman at one point makes the mistake of saying that Holly Golightly bought some furniture from the estate of William Randolph Hearst, who died in 1951, which is-- He got a little confused sometimes between the period he was writing the book and the period it was alleged to be set, but I don't know, I just feel almost as if I'm there. His descriptions were just perfect. His descriptions of people, but also of the landscape of the apartment building, of the neighborhood. That really was one of the great New York books, I think.

John Burnham Schwartz: I think he had a way of capturing in prose the layers of both a person and a place, all the different layers, the sort of shiny surface and the effort that would go into that, the style of something and also underneath some of the things that are hidden, some of the sadder or more poignant elements. I think Holly Golightly remains outside of our idea of Audrey Hepburn in the movie, remains such an iconic character because when you go back and read the book, you see all of that.

You see this small town, unhappy, abandoned girl who has recreated herself, who's very much like Truman, who came from Alabama to the north when he was 11. It was sort of riven between these two sides of the outsider and the would-be insider.

Jay McInerney: People talk about Carol Marcus or Oona O'Neill being possible models for Holly Golightly, but I think John is right that Truman himself was as much the model for Holly as anybody, because he was completely self-created. A Southerner who wanted desperately to be a New Yorker and became one of the archetypal New Yorkers.

Alison Stewart: We actually have a bit of audio from the 92nd Street Archives. This is Truman Capote reading from Breakfast at Tiffany's. This is from April 7 1963, with a great little introduction.

Jay McInerney: Wow.

Truman Capote: Wait a second. Well, the time of the setting, the time of this story is during 1943, during the war. And the narrator of the story has just moved into a house and living above him is a Japanese photographer, Mr. Yunioshi, and that's all you need to know at this point. "I've got the most terrifying man downstairs," she said, stepping off the fire escape into the room. "I mean, he's sweet when he isn't drunk, but let him start lapping up the vino and, oh God quell beast. If there's one thing I loathe, it's men who bite." She loosened a gray flannel robe off her shoulder to show me evidence of what happens if a man bites.

The robe was all she was wearing. "I'm sorry if I frightened you, but when the beast got so tiresome, I just went out the window. I think he thinks I'm in the bathroom. Not that I give a damn what he thinks. To hell with him. He'll get tired. He'll go to sleep. My God, he should. Eight martinis before dinner and enough wine to wash an elephant."

Alison Stewart: If you've never read the original novella, why is it worth picking up?

John Burnham Schwartz: I need to say, Jay and I are sitting here laughing for, I think, a couple of reasons. One is just-

Alison Stewart: The voice.

John Burnham Schwartz: -his voice is just believable.

Jay McInerney: Yeah, well, I mean, you heard it a lot, but--

John Burnham Schwartz: I did and it was almost a surprise for me hearing it again.

Alison Stewart: But he also had a really deep laugh, like a manly laugh at the end of it.

John Burnham Schwartz: Yes. Again, there's various sides of Truman. The other thing we were laughing was the man upstairs, Yunioshi-

Jay McInerney: Yunioshi.

John Burnham Schwartz: -was played horribly by Mickey Rooney.

Jay McInerney: Mickey Rooney with buck teeth.

John Burnham Schwartz: Buck teeth and just totally not okay.

Alison Stewart: Not okay.

John Burnham Schwartz: Yeah. It would not fly today but I still think in the city that now is sort of like a country club to live in, it's its own expensive fortress, but there's still people coming here to completely recreate themselves. The idea of living in this building, even a small one like that where your neighbors are a variety of people sort of like you. He himself, the narrator is in the novel, his sexuality is not clear. It appears the intimation is that he's something of, as Truman said, an American geisha much like Holly Golightly.

Jay McInerney: Well, he's a gigolo basically.

John Burnham Schwartz: Yeah. And the movie, all of that was sort of softened up in the movie, but-

Jay McInerney: George Peppard.

John Burnham Schwartz: -George Peppard, but it makes for an incredibly-- underneath the wonderful comedy and the music of her exuberance, if you will, it makes for a really complicated, wonderful, socially rich tapestry. And the prose is just-- the dialogue is great too. It's just great.

Jay McInerney: But I think it is the archetypal New York story. Some provincial comes to New York to completely reinvent themselves. And Holly is a wonderful character. We learned just enough about her to be utterly intrigued with that. There is one point when her background I think is maybe a little bit over described-

John Burnham Schwartz: Yes.

Jay McInerney: -but she's just a great character. And in some ways, people like this from small town Texas and Louisiana become the archetypal New Yorkers as she certainly is.

Alison Stewart: Well, so many people became familiar with Truman Capote from his portrayal on To Kill a Mockingbird as Dill Harris, Harper Lee wrote about him, this little kid who comes over and wants to be in everything. What do we learn about him from Dill?

John Burnham Schwartz: It is true that when he was living in Monroeville, Alabama and his neighbor with his mother's relatives, all of them female, and his neighbor and friend was Harper Lee, and he would go around with a dictionary from the time he was five. He taught himself to read and write at an incredibly early age. He was literally writing and he produced a story. I think it was called Mrs. Busybody or something like that and it was literally a gossipy account of the sort of crazy stuff that was that the neighbors were getting up to.

Her father was a trial lawyer and they would go to trials sometimes to just pass the time. And so I think just the inquisitiveness. His nickname when he was young was Bulldog. I was actually bitten by his bulldog Maggie once when I was a kid. Just throwing that in there. But I think there was a toughness and a pursuit and a sort of single mindedness even as there was this curiosity and willing to talk to everybody, high or low.

Alison Stewart: Let's take a call. Ellen is calling in from the Bronx. Hi Ellen, thanks for calling All Of It.

Ellen: Thank you for taking my call. We are holding a 100th birthday party for Truman tomorrow night at Brooklyn College.

John Burnham Schwartz: Wow.

Ellen: And I want to say something about the regenerate Truman Capote. He was very interested in supporting young writers. Through the Truman Capote Trust, as administered by Louise and Alan Schwartz, we have become at Brooklyn, our MFA program, the recipients of Truman Capote Fellowships and we have invited all the past and present Truman Capote Fellowships and Louise Schwartz. We will be celebrating, as I said, tomorrow night, and we are very, very grateful for the support that the Capote Trust has given us from 2012 through the present.

Alison Stewart: Thanks for calling in, Ellen.

John Burnham Schwartz: Yeah, I mean, just to jump in because Louise Schwartz is my stepmother and Alan Schwartz, who founded the Capote Trust is my dad. I thank you so much for calling. I think it's fantastic. They've been giving out so many scholarships. This was in Truman's will. It was what he wanted. And there's a prize that they give every year too for literary criticism. It's called the Newton Arvin Prize. Newton Arvin was probably Truman's first real lover. He was a professor at Smith College and he was eventually ousted from his career for his homosexuality. And so he wanted this prize in literary criticism. Newton Arvin was a was a wonderful literary critic.

All of these creative writing and literary criticism grants and prizes have been given, and it's great to think that they're gathering here while before the year is out.

Jay McInerney: I feel like his royalties must be significant because those books are very much alive.

John Burnham Schwartz: I have to say, I think my parents have done an incredible job with the trust, and it is significant. They've really been able to give prizes all around the country to many, many different kinds of institutions and writers and so that's very cool.

Jay McInerney: Yeah.

Alison Stewart: My guests are author Jay McInerney and John Burnham Schwartz. We are discussing the life and legacy of Truman Capote, who would have turned 100 this year. Jay and John will be guests at the 92nd Street Y. It's an event honoring Capote tomorrow night at 8:00 PM. We want to know what's your favorite work by Truman Capote and why? Could be a novel, could be a short story, or maybe you met Truman Capote once. Our phone number is 212-433-9692, 212-433-WNYC. After the break, we'll talk In Cold Blood.

[MUSIC]

Alison Stewart: You are listening to All Of It on WNYC. I'm Alison Stewart. My guests in studio are Jay McInerney and John Burnham Schwartz. We are discussing and legacy of Truman Capote, who would have turned 100 this year. Jay and John will be guests at the 92nd Street Y honoring Truman Capote tomorrow night at 8:00 PM. I got this great line. Someone texted in, "My favorite Truman line from In Cold Blood when Perry says, or was it Dick? It says we're going to blow hair all over those walls about the Clutters. Read that in high school almost 40 years ago and think about it. Pretty much every time I see blood, hair or walls."

When you're thinking about In Cold Blood, sort of a new nonfiction novel about the murder of a family in Kansas, why do you think this has remained a classic, John?

John Burnham Schwartz: I think first of all, it's just an extraordinary story, and it's written from first to last with the intention of making great art. Truman used to talk about his relationship with Perry Smith, who is, I think, unquestionably the most fascinating character in the book, who was one of the murderers and was somewhat-- he was both handsome and deformed. He was short. He was an outsider. He was probably gay. He was all of these different things. The relationship, though Truman never appears in the book, the relationship between author and subject is quite extraordinary.

I think it's a book that-- I know somebody who's taught that book in prisons. One of the reasons they've taught it in prison is because it's one of the first books to ever treat the murderers as subjects and treat them as human beings in the sense of what their lives were like, what their thoughts were like. He spent four or five years writing two letters a week back and forth with Dick Hickok and Perry Smith. Then he had to wait, famously, after the book was done in order to fully finish the book for them to be executed. I think all of that attention, beyond the murder itself, creates something that's indelible and that does not date.

Jay McInerney: Yeah, and he essentially created a genre, which others imitated, including his sometime friend, Norman Mailer, famously. I read it three times, I guess, and it doesn't feel dated in any way, and it doesn't seem to get old. I think what John said about Perry is very true, that Truman really did identify with Perry Smith. There's certainly the rumor out there that they were lovers and that they were indulged in this by the prison staff.

Regardless, his ability to treat the murderers as human beings, even as he portrays, as that line from our caller suggests, that treats the crime as a horrific crime and doesn't flinch in any way from describing the horror of it. He is still able to treat the murderers with sympathy and understanding and that's one of the great achievements of the book. I still find it amazing that the book is, in many ways, is so unpredictable from Truman Capote. Here was a sort of almost Southern gothic writer who wrote fairly precious novellas who suddenly goes to Kansas and-- I mean, he could have just made a New Yorker article out of it and--

Alison Stewart: He was trying to decide and The New Yorker gave him the assignment, "You want to do that or something else more Truman Capote-ish?"

Jay McInerney: Yeah, but then he stays, what was it John, four or five years?

John Burnham Schwartz: He himself said that he saw that he sort of had two different careers. There was basically 1948-'58, which is when-- 1948 is when Other Voices, Other Rooms, he arrives on the scene with this first novel that's a bestseller in The Times list and he becomes a sensation. Then 1958 is Breakfast at Tiffany's. He set about paring his style and he was also, as Jay's suggested-- he saw journalism as this untapped resource literary mode that he felt could be an extraordinary vehicle.

If you go back earlier in the '50s, 1956, in The New Yorker, he does a series of nonfiction pieces. It ends up being published as a book called the Muses Are Heard. It's an incredible book actually and it's he goes with this Black American theater troupe to the Soviet Union. First theatrical exchange between these two countries ever and they're doing a production of Porgy and Bess throughout the Soviet Union and Truman details this whole trip. It's an incredible book.

He said he was preparing himself to try and find a bigger topic and make the big swing. That's finally-- he tried two or three different things that didn't work out and then famously, he sees this little news item in The Times about this murder in Kansas. He and Harper Lee, who had just finished but not yet published To Kill a Mockingbird, go on down to Kansas, to western Kansas.

Alison Stewart: Let's take a call. This is Judy calling in from Howell, New Jersey. Hi, Judy. Thank you so much for calling all of it.

Judy: Hi, thank you for taking my call. My favorite book by Truman Capote is this little book called A Christmas Memory.

Jay McInerney: I was going to mention that one. Good.

Alison Stewart: Tell us why.

Judy: It's a lovely little book. It's about him when he was living as a child with his aunts. One aunt in particular was mentally challenged and they had quite a friendship. At Christmas time, they decided they would make 30 fruitcakes and so they had to go all around the neighborhood and it's about the people they met and getting the ingredients. It's just a warm, beautiful story and I read it every Christmas.

Jay McInerney: Yeah, I made it a tradition in our household that I read it every Christmas for seven or eight years with my parents and my brothers. It's a very beautiful story.

Alison Stewart: What short story would you tell people to read, John?

John Burnham Schwartz: I mean, that's one of them. There's a story, Miriam, which won the Mademoiselle Prize in 1946, when he was-- That's what actually got the attention of Bennett Cerf, which led to his contract for Other Voices, Other Rooms. He was so young, but he focused so much attention on the short stories in those early years. He was publishing them all over. Miriam's a great story. I'm trying to think of some others.

You can get the Collected Stories, which I really recommend, and just pick your way through them. He had a theory that basically, every story has its natural form for what it is. What he would do when he finished the story was go back and try and imagine if there was any other way of telling it. If he couldn't find another way of telling it, then he felt that he had arrived at the right way. You can see the prose just taking shape and just working on it all the way and I think it's some of his best work in many ways.

Jay McInerney: I think he was truly a great prose stylist. That was what, as an aspiring writer, inspired me, was reading his sentences and appreciating the rhythm of them and appreciating the perfection of expression. Certainly, by the time of Breakfast at Tiffany's, he had achieved a perfect style. The early books are a little bit baroque, I guess.

John Burnham Schwartz: Yes, yes. A little Gothic, Southern Gothic, baroque, whatever.

Jay McInerney: Yeah, but he was a great stylist. As, again, Norman Mailer--

John Burnham Schwartz: He said he's the most perfect writer of our generation. Although, when you think about Norman, you have to assume that maybe there was a bit of an edge to the word perfect, not entirely a compliment.

Alison Stewart: The most recent sort of, I don't know, example of Truman Capote is Feud, right, Capote vs. The Swans. Molly Ringwald's going to be at this event tomorrow at the 92nd Street Y. It's about Truman's betrayal of his friends, in our crowd in New York society, these women. God, it was so thinly veiled. His writing about them was so thinly veiled. I think at one point he even said, "I'm a writer. That's what people should expect from me. I'm looking for content." Well, he didn't say content, but you know what I mean. As writers yourselves, do you think he crossed the line?

John Burnham Schwartz: I do think he crossed the line and I think he crossed the line by running out of-- I think the connection between himself and his imagination basically broke down through a series of assaults, chemical, alcoholic and his relationship with the society around him. I think when you are an outsider, and if you look back at all of his stories early on in those first 15 years, they're really about outsiders of different kinds. The implication may be they're queer or in terms of class or whatever it is, but he identified with the outsiders, and then there's this anger that builds.

I don't think he knew where the line was at the end. He started talking about Answered Prayers, which is what these stories became back in 1958 and he saw it as this Proustian endeavor that was going to be his great masterwork, but I think he lost sight of where the writer was. He had always been very careful to be an objective observer, and I think he lost sight of that, and he no longer had a sense of where he stood as the author or the person.

Jay McInerney: Yeah, well, certainly as a friend, he crossed a line on most of these stories. By the way, there are four of these stories that basically shattered his relations with the various swans, various friends of his, people to whom he had been a confidant and an intimate for many, many years, and people who assumed that as his friends, they would be spared from his, to some extent, from his wit and--

Alison Stewart: Wicked wit.

Jay McInerney: It's wicked, yeah. I think, as John alluded to, these stories were not reimagined much in any way. They were pretty much gossip typed out and published by Esquire.

John Burnham Schwartz: I would say only that I think the actors in the show were fantastic and everything. I think the show to some degree, reenacts how Jay just described Truman's fault in Answered Prayers because it so doubles down on only that particular side of him. That said, he will forever be known as both these things. It does, on the one hand, make him still one of the best, the most famous writers of the second half of the 20th century, and at the same time, it muddies his literary legacy, and that's why we're here in a way.

Jay McInerney: John and I were talking earlier about whether Answered Prayers exists in any form other than these four short stories that were allegedly part of it. I think we both feel like if there was more, he would have made sure that it was preserved and eventually published.

Alison Stewart: You can hear more about Truman Capote tomorrow night at the 92nd Street Y. The event is starting at 8:00 PM. My guests have been Jay McInerney and John Burnham Schwartz. Thank you so much for coming to the studio.

John Burnham Schwartz: Thanks for having us.