The Schomburg Center Celebrates its Centennial

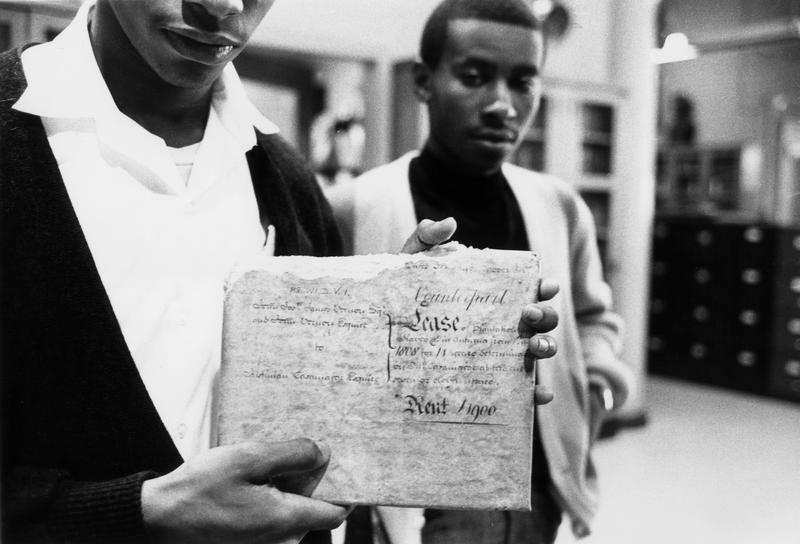

( Photo by Sylvia Plachy/Three Lions/Getty Images )

Alison Stewart: This is All Of It. I'm Alison Stewart, live from the WNYC Studios in Soho. Thank you for spending part of your day with us. I'm really grateful that you are here.

On today's show, we'll hear a live performance by local bossa nova musicians John Roseboro and Mei Semones, and we'll talk about a new book that explores high-achieving siblings. That's the plan, so let's get this started with 100 years of the Schomburg.

[music]

Alison Stewart: This week marks the 100th birthday of an uptown institution, a national historic landmark, the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture. On May 8th, 1925, the New York Public Library opened a new division at its 135th Street branch, the Division of Negro Literature, History and Prints. The Division is now the Schomburg, and it holds an extensive collection of Arturo Schomburg, a Black Puerto Rican man. Schomburg dedicated his life to preserving artifacts of Black culture after he was told as a child that Black history didn't matter.

The Schomburg now has over 11 million objects in its collection, some of which you can see on view starting this Thursday. To celebrate its centennial, the Schomburg Center has organized an array of public programs and a new exhibition. It's called 100: A Century of Collections, Community, and Creativity. It opens to the public on May 8th. Joy Bivins is the director of the Schomburg. She curated this exhibition, and she is with me now. Welcome to WNYC.

Joy Bivins: Thank you. Thank you for having me today. I really appreciate it.

Alison Stewart: I want to say congratulations. 100 years.

Joy Bivins: 100 years. It really is quite amazing, and I feel very privileged to be here at this moment in this institution's history.

Alison Stewart: As you started curating for this event, what themes did you know that you most wanted to explore around the centennial of the Schomburg?

Joy Bivins: Well, I've been at the Schomburg Center now for almost five years, and one of the things that has always excited me and enticed me at this institution is the robust collections. Also, I was drawn to images of folks in the early reading room, so like 1925, dedicated or engaged in deep study and deep reading of books, and being surrounded by material culture that really reflected places in the African diaspora. That is ultimately part of the inspiration for this exhibition, really thinking about the ways in which the collections are at our core. This is part of our ethos.

We are surrounded by a community that makes that possible. We emerged during the Harlem Renaissance. This is a community of writers, artists, and meaning makers, so we are supported by that community. Through these objects, as well as through the community, creativity is abounding, and we wanted to really look at the interplay of all of those things. I've been in this degree of threes recently, so everything is like three threes and alliteration, ultimately.

Alison Stewart: You had so many things to choose from for this collection. How did you possibly select objects to be in the centennial exhibition? What was the process like? What was your criteria?

Joy Bivins: It's an embarrassment of riches in many ways. I've been working on exhibitions for a long time, and sometimes-- I've never been in a situation where I had too much to choose from, or maybe one time. That does then make it difficult to make some selections. What we did early on is really engage curators in our collecting divisions, who are the experts, who have deep knowledge of these materials, and wanted to see, could they bring out things that were related to our history, to our genesis, if you will, and then also things that excited them and things that people would be surprised to see at the Schomburg Center.

The criteria was ultimately like, what can we share with our guests, some of which they know about – Malcolm X, James Baldwin, Maya Angelou. Some of our rich art collections, which maybe people are not as familiar with, but is really very deeply grounded in our beginning. Then some of these rare books that I'm just like, "How? How do we have this?" I think during our development, we always talked about wanting to tell a story, but at some point, I was like, "We just need to flex." We just need to use these objects to be like, "This is here. This is in your community. This is available to you."

Part of the story of the Schomburg and why there are so many rich collections is because it has such a jump on other institutions that are now catching up and realizing the importance of Black material culture, Black intellectual history, Black artistic history, and whether that's in the United States, the Caribbean, or on the continent. I think there was so much to choose from that it really became like, "Let's just put as much out there as we possibly can."

Alison Stewart: All right. I want to know what a flex is. Tell me something that's a flex.

Joy Bivins: [chuckles] A flex is including Elizabeth Catlett. A flex is including Tschabalala Self. This is a new acquisition. A flex is including Roy DeCarava. A flex is included a rare book, rare manuscripts from the 16th century. These are flexes. I think folks really do have a sense of our deep collections because we serve researchers and have always been in the business of doing exhibitions and programming. Sometimes you just got to let people know. This is the Schomburg Center.

Alison Stewart: My guest is Joy Bivins, director of the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture. We're speaking about the Schomburg centennial. It's commemorated with the new exhibition Joy curated, called 100: A Century of Collections, Community, and Creativity. It opens on May 8th, the day of the Schomburg's original division when it first opened in 1925.

Hey, listeners, let's get you in on this conversation. You want to wish the Schomburg a happy 100th? How has the Center been important to you in your life? What is the coolest thing you've seen at the Schomburg? Maybe you're a student or a scholar who's relied on the Schomburg's archives for research. What was the project you were working on? What did you learn at the Schomburg? Our phone number is 212-433-9692, 212-433-WNYC. If you live in Harlem, what does it mean to you to have the Schomburg there in your neighborhood? Give us a call. 212-433-9692, 212-433-WNYC.

Let's go all the way back 100 years. It began as the Division of Negro Literature, History, and Prints. How and why did this division open?

Joy Bivins: As I mentioned, we are emerging during the Harlem Renaissance, but we're also emerging, or we emerged at a time where there is a cadre, a group of folks who are really interested in the Black past, who are collectors, who understand the importance of knowing Black history. I was thinking about this earlier. Next year is also really the 100th of Negro History Week, right? The Division of Negro Literature, History and Prints, Negro History Week, the Association for the Study of Africa, now African American Life and History, all these things are happening, percolating at the same time.

Arturo Schomburg was a member of history clubs. He did lectures. I think part of the reason that this division started is really to satiate a community that wants to know more about who they are, right? By the time we open in 1925, Harlem has changed. It is a mecca of the Harlem-- on the renaissance, if you will. The demographics have changed. People are using the 135th Street branch library and voraciously consuming anything that has to do with the Black past.

Instead of just having that keep happening, there was a group of folks that got together and said, "Why don't we start a division that really develops a collection that is just special and cannot be taken out of the library, has to be used here in the library. This is where that comes from. Again, it really is this intersection of the needs of the community, the creativity of the librarians here, Ernestine Rose, Catherine Latimer. The creativity of Arturo Schomburg, other community organizers, to really make sure that the collection is here so that it can serve the community. There's always this kind of back-and-forth that's going on here, and that's why we came to be.

Alison Stewart: What do people need to know about Arturo Schomburg?

Joy Bivins: What people need to know about Arturo Schomburg, born in Puerto Rico in 1874. As a child, he had a deep interest in history, and was told by a teacher, when he asked the question, "Why don't we learn anything about Africa or Black people?" and the instructor said, "Well, there's no history to talk about from that part of the world." I think that he knew this was not true. Based on the community that he grew up in, he knew this was not true. For his life, he really was in the pursuit of what he called vindicating evidences that really show the contributions, the accomplishments of Black people. Not just to the history of this country or this hemisphere, but really global history.

I think it's John Henrik Clark who says - scholar John Henrik Clark – that really what Arturo Schomburg was trying to do is fill in these missing pages of global history. He does that kind of relentlessly with collecting pamphlets and manuscripts and rare books and prints. The art is always part of it. He outgrows it in his home, but it is a well-known collection.

Arturo Schomburg was a collector. When he came to the United States as a teenager, he was involved in anti-colonial movements for the freedom of Puerto Rico, for the freedom of Cuba. So he is always connected to a larger diaspora. He's always thinking about what are those things that people need to understand their history. We all know that history is political, and being without memory is a dangerous thing. I think these are the ways in which he is cultivating a collection so that people can understand really what Black folks have done throughout world history.

Alison Stewart: We got a funny text. It says, "Just want to say I flex with my Schomburg Center tote, kind of like I do with my WNYC tote. It makes me look like I know stuff. [laughs] Love that.

Joy Bivins: That's a member there.

Alison Stewart: There you go.

Joy Bivins: Because we know that is part of your membership package to get a tote.

Alison Stewart: This says, "When I taught studio art at BMCC, one of my students who lived uptown said he had no place to do his work at. I suggested he use the library. He discovered the Schomburg and said the most valuable thing he got from my class was that he also caught up with his assignments, and he passed.

Joy Bivins: Oh. Well, this is wonderful.

Alison Stewart: We love hearing that. We want to celebrate the Schomburg's 100th birthday. We're with Joy Bivins, director of the Schomburg Center. She has a new exhibit called 100: A Century of Collections, Community and Creativity. We want hear from you. What's the coolest thing you've ever seen at the Schomburg? Or maybe you're a student or a scholar who's relied on the Schomburg's archives for your research. Tell us what your project was. Give us a call at 212-433-9692, 212-433-WNYC. You can text to us or you can join us on air.

You are displaying four murals by Aaron Douglas, the Aspects of Negro Life series. He gifted these to Arturo Schomburg. What is important to know about these murals?

Joy Bivins: These murals, the Aspects of Negro Life by Aaron Douglas were commissioned actually for the 135th Street branch Library. They are part of the public works art project. This is depression era federal funding, if you will, to produce art that is important to community and citizens. Aaron Douglas produced four murals that really trace the history of Black people, really thinking about being grounded in Africa, moving to rural spaces, the Great Migration, and then the settling into these new northern midwestern urban locations. It's doing this in a very rich textural way through color, through images of the city, through images of the plantation.

There was a image of a man pointing to the city on a hill, really thinking about what's drawing Black people through their history. Through that, you get a history of Black people era by era, and it is, again, when we talk about the importance of art, not just because it's visually stunning, but also because it is a way to tell stories. This is one that can be read very deeply. It is usually in our reading room in our Jean Blackwell Hutson General Research and Reference Division. We brought them up to one of our galleries upstairs so that people could have an experience with them.

Alison Stewart: I want to ask you about a couple people that you've mentioned who are important to the history of the Schomburg. Catherine Latimer, the first Black librarian in the New York Public Library system. Tell us a little bit about her, what she did at the Schomburg.

Joy Bivins: Well, Catherine Latimer was here-- I think she was hired in 1920, so right after Ernestine Rose, who is also spearheading so much that's happening here at the 135th Street branch library. Catherine Latimer is, as you said, the first Black librarian at the New York Public Library system. She is exceptional in that, but she becomes part of a cadre of Black librarians who are really working hard to make sure that researchers have what they need. If you think about this, when she started, we're not in Library of Congress catalog headings. Along with peers who joined her later, they are really writing Black people into library information systems.

This is something we wanted to look at as well because this is creativity. It may not be painting and it may not be writing poems, but it is a way in which you are utilizing your training as an information scientist, if you will, to think about how we can bring in other voices and those that have been on the margins. Along with other librarians, they're indexing, they're creating scrapbooks. They're finding things that are written about Black people so that other Black people can find them. They're doing bibliographies. This is down-and-dirty work, but also very creative and also very necessary.

Not only is this a place where collections are being kept, this is also a place where the infrastructure, what would become Black Studies, is being developed as well.

Alison Stewart: You mentioned Jean Blackwell Huston? Huston, Houston?

Joy Bivins: Hutson.

Alison Stewart: Hutson. Thank you. Jean Blackwell Hutson, the former chief of the Schomburg Center. What was her impact on the organization?

Joy Bivins: She was here from '48. She began in 1948. Actually, she was here before then. She was here briefly when Arturo Schomburg was here. I think she started in '36, went away, did some other things, came back in '48, and was basically here until this new building was erected in the early '80s. Under her, we moved from the Schomburg Collection, part of a branch library, to the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture. We move from a collection at a branch library to a research library. This is important because collections in research libraries are protected in a different way.

You have the storage, and you have to think about HVAC. You have to think about all those things that are needed to ensure the proper stewardship of these objects. Also, research libraries are not dependent per se on city funding. It becomes another aspect of protection of the collection, and another aspect of really elevating a collection that many knew about to a different level. Her impact on what is the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture can't really be overstated. I was telling your colleague before that she was often on WNYC talking about the Schomburg Center.

Alison Stewart: Well, it's really interesting. From one of our colleagues, she sent us a picture. It's on my desk right here. It's the opening of the new building from September 1980. It's a picture. It says, "I grew up with this beautiful poster of the opening of the new building. As a 50-year-old, I still find wonder in the story that is told in this poster, sharing a collective memory of history and celebration."

Joy Bivins: Yes.

Alison Stewart: We also got a note that says, "I was an adult before I learned about the Schomburg, but I would have loved to have been able to avail myself of it as a kid." This one says, "Every time someone visits me in New York City, I make sure to take them to the Schomburg. One of the best things I always look forward to is participating in the annual Black Comic Book Festival."

Joy Bivins: Ahhhhh, yes. Yes. Another part of our legacy is that from the beginning, there were programs, there were lectures, there were readings, there was education happening in that 135th Street branch library. Exhibition of Black art, where else are Black artists going to exhibit their work? Always bringing people into the fold in different ways, because not everybody is going to go into the reading room. Not everybody perceives themselves as researchers, although I think everybody is a researcher or has the possibility of being a researcher.

The programs are another way of activating curiosity and creativity. This year, the Black Comic Book Festival is going to be part of our centennial festival in June. We're combining forces – the literary fest, the Black Comic Book Festival – and thinking of this as kind of a block party, if you will, to celebrate all things literary. The Black Comic Book Festival will be part of that. There will still be-- folks can still come in their cosplay, if they choose to, because that's a big part of the Comic Book Festival.

Alison Stewart: We're talking about the Schomburg celebrating its 100th birthday. My guest is Joy Bivins, director of the Schomburg Center. We'll have more after a quick break. This is All Of It.

[music]

Alison Stewart: You are listening to All Of It on WNYC. I'm Alison Stewart. My guest is Joy Bivins, director of the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture. We're speaking about the Schomburg centennial as well as the exhibition that Joy curated. It's called 100: A Century of Collections, Community, and Creativity. We're also taking your call. Let's talk to Sheila, calling in from the West Village. Hey, Sheila.

Sheila: Hi. I'm glad to talk to you. My name is Sheila. I'm in the West Village, and I'm not Black, I'm white. I was studying Art History at City University with George Preston, and I went to the Schomburg to get the kind of information that I needed for the course. I just found it so rich and so welcoming and so important. Also, I went there for a concert that Nasheet Waits gave with his quartet years ago, and that was so marvelous. I just want to open it up to make everybody realize that this is not just for Harlem. This is for the whole city. It's a very, very important cultural center.

Alison Stewart: Sheila, thank you for your call.

Joy Bivins: Thank you. Thank you, Sheila.

Alison Stewart: I'm sort of interested. What are some of the notable projects that have relied on the collections at the Schomburg?

Joy Bivins: Notable projects? By that, do you mean books or do you mean--

Alison Stewart: Yes. Just books that we've read and we haven't realized, like, "Oh wow, that author spent a lot of time in the Schomburg."

Joy Bivins: Thinking about Eddie Glaude's book on James Baldwin, Imani Perry's book on Lorraine Hansberry, whose papers we also have the film on Malcolm X by Spike Lee, I think in ways in which people can immerse themselves both in the archives, but also thinking of archives broadly. There is film here, there is music here. We collect across medium. A lot of times, people begin their research here at the Schomburg and then take that further and create things. I also want to lift up artists like Jacob Lawrence, who said he would come here as a young man and read the books at the Schomburg Center.

Go home, take that information, translate it into paintings that are so-- Sorry, there's an ambulance behind me. That are so important to not just the African American art canon, but the American art canon, the global art canon, if you will. I'm thinking of Sonia Sanchez, poet Sonia Sanchez, who arrives here as a young woman wondering what we do at the 135th Street branch library. She meets Jean Blackwell Hutson, who introduces her to a world of Black literature, things she had not yet encountered, even as an educated young woman.

There are all of these people who are connected to our story. I just gave you a few. I haven't even talked about the American Negro Theater, which was here from 1940 to 1945. This is where Harry Belafonte began his career, along with Ruby Dee, Ossie Davis. I think that, again, we're going back to this notion that we're a library, but we're also doing multiple things, and have always been doing multiple things. Because when we start, the city is not open to people of African descent the way it is now.

I think this is always important to remember the ways in which we envision our lives are different than what our predecessors were able to experience. If you needed it, you could come to the 135th Street branch library or the Schomburg Center.

Alison Stewart: I spent a lot of time in the Schomburg preparing to write my book, so I understand what you mean about it. It's sort of seeping into you. It was really great. This text is so good. When I moved to New York in the 2000s, one of my first jobs was installing the Aaron Douglas exhibition. I worked there another 10 years and got to learn about and experience so much about Black art and Black culture. I also met my wife because of that gig. A lot of love to everyone at the library, and shout out to Tammi Lawson and JR.

Joy Bivins: Oh, okay. Okay, fantastic. Well, Tammi is our curator of art and artifacts, so if you want to know what's in this collection, you talk to the curators about that.

Alison Stewart: This shout-out to Schomburg architect J. Max Bond, important practitioner, mentor, professor at Columbia, and dean at CCNY. Before we run out of time, I want to find out what's happening at the celebration this Thursday and this summer. Ready? Go.

Joy Bivins: This Thursday, we are welcoming the public starting at 12 noon. We will have a spiritual ceremony to get things started. Programming, I'll be in conversation with Howard Dodson and Khalil Muhammad, my predecessors, about the Schomburg. We will have Denise Murell, Veronica Chambers here to talk about the Harlem Renaissance, so we ground ourselves in that history. Then we close to start getting ready for the party that will happen that evening. Then this summer, we will have our centennial festival. We are kicking off tasting the Schomburg collections, which are dinners that are inspired by our collection of cookbooks with chefs like Marcus Samuelsson. That's the first one.

In September, we will have our first annual Jean Blackwell Hutson lecture and award. We will continue the party that year with programs that include film screenings and theater screenings, and a program called Portrait of an Icon. I'm trying to remember it all. There's a lot to remember. There's a lot to think about. There's a lot going on here at the Schomburg.

Alison Stewart: We should go to their website.

Joy Bivins: Yes, you should.

Alison Stewart: Yes. Joy Bivins is the director of the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture. You want to give the website real quick?

Joy Bivins: Sure. Schomburg.org/100, for everything.

Alison Stewart: Happy 100th birthday to the Schomburg. Thank you for being with us, Joy.

Joy Bivins: Thank you. Thank you so much.