'The Meathead Method' Of Barbecuing

Alison Stewart: This is All Of It on WNYC. I'm Alison Stewart. Hey, a quick reminder. We've been reading our May Get Lit with All Of It book club pick, and it's almost time to discuss. The novel is auditioned by Katie Kitamura, and we will meet on Thursday, May 29th at 6:00 PM at the New York Public Library, Stavros Niarchos Foundation branch. Tickets are free, but there are only a few left, so get yours now by going to wnyc.org/getlit. Plus, our special musical guest is a musician and a Broadway star, Reeve Carney. Again, that's happening next Thursday, May 29th. The book, it's under 200 pages. You can get it done this weekend. Tickets and more information can be found at wnyc.org/getlit. That's in the future. Now let's get this hour started with Meathead.

[music]

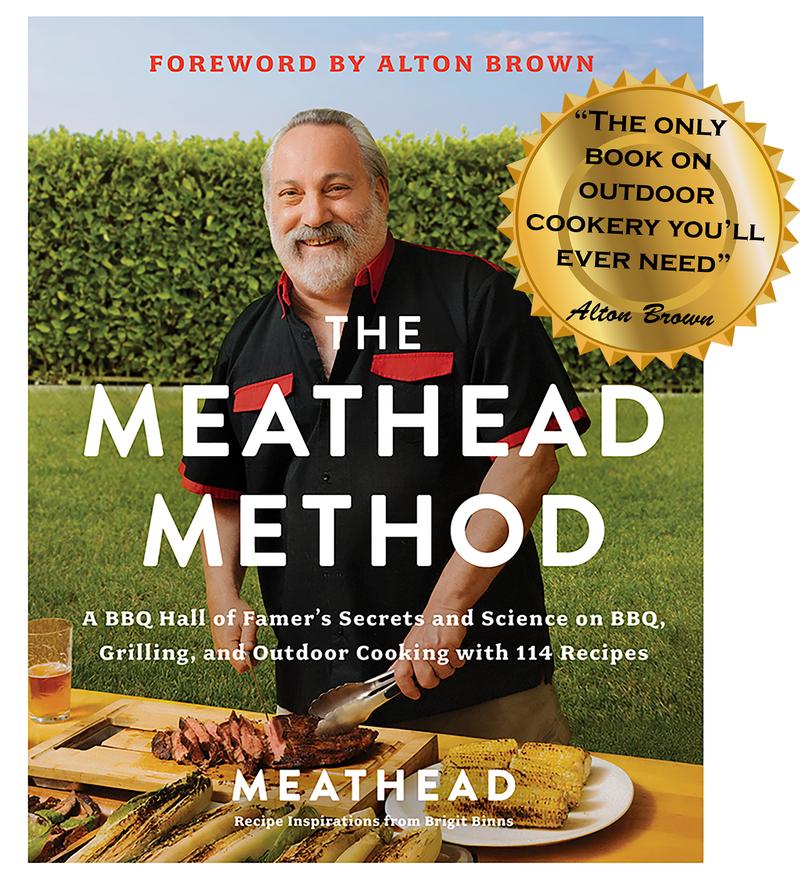

Alison Stewart: Memorial Day right around the corner. Some of you are probably thinking about pulling out the grill to throw on some ribs, burgers, maybe a few vegetable skewers, too. A new cookbook titled The Meathead Method explains the core principles and science behind cooking food over an open flame. It's the second cookbook from barbecue hall of famer Meathead. In the forward, longtime Food Network TV host Alton Brown writes, "The Meathead Method is his grand opus and, honestly, probably the only book on outdoor cookery that you'll ever need. It includes 114 recipes for dishes like buttered-up turkey breasts with drunken cranberries and crunchy skin." Nice.

"However, in the process of learning how to prepare these recipes, you'll also develop an understanding of cooking, how enzymes can help us digest food, and the difference between wet brining and dry brining, or how to read a label." The Meathead Method is out now. Joining me to discuss this is Meathead. Hey, Meathead.

Meathead: Hello, Alison. Why you read the book?

Alison Stewart: There you go.

Meathead: Thank you.

Alison Stewart: Right here. I got pages numbered. I'm ready to go. Listen--

Meathead: Excellent. It's a fun book, and it was a labor of love. The first half of the book is like a science book. It's a textbook. I'm kind of a geek. The art world has different movements like the Impressionists and the Fauvists, and the Modernists. The culinary arts, which is a fine art, has a movement now that I call the nerdists, and that's Alton Brown and Christopher Kimball, and myself. We're geeks and we're into the science. There's a lot of the science stuff in here, but hopefully it's not too complicated.

Alison Stewart: What got you interested into the science of outdoor cooking?

Meathead: I've always been interested in science, even when I go back to high school. I won a science fair once. If you're cooking, whenever you step foot in the kitchen or out on your grill deck, you're conducting a chemistry and physics experiment. You're applying energy in the form of heat to proteins and fats, and carbohydrates. What happens when they interact? What is fire? What is smoke? I'm just a cook, and I wanted to know this, and I'm not alone. As I say, there's a bunch of other chefs and TV cooks who are really into it, who are geeky nerdists.

What I've done is I've taken what I've learned. We've done a lot of fun testing, experimenting, things that we-- I learned to grill from my dad, and he learned to grill from his dad, and he learned to grill from his dad. There's a lot of mythology that follows barbecue down to the common person today. We have a lot of cool science out there. A lot of universities have food science departments, meat science departments, and they're learning that a lot of the stuff in our cookbooks is out of date.

Alison Stewart: What's an example of a myth that you bust in the book?

Meathead: There's a classic for barbecue, and that is, you need to soak your wood for an hour, some say, some say overnight, but you need to soak your wood. There's a reason they build boats out of wood, because wood doesn't absorb water. We did the test. It's such a simple kitchen test. Do it yourself at home. Get a handful of your wood chips or your wood chunks and soak them in water for an hour. Soak them overnight. Weigh them first, then soak them, weigh them, take them out, pat the surface water off, and weigh them again. There's about a 3%, 4% weight gain, and that's just because there's some water on the surface of the wood.

If you cut the wood chunk open, there's no water inside. When you throw wet wood on charcoal or gas, you think you're getting a lot of smoke, but it's not. It's steam. Water boils at 212 degrees. You've got to heat that water up to 212, get rid of it, get it off the surface of the wood before the wood can start to heat up beyond 212, because it won't start smoking to 500. When you throw wet wood on a fire, that's not smoke, it's steam. It doesn't start smoking until you get to 500. Soaking your wood actually inhibits smoke formation.

Alison Stewart: In your book, you write, "Yes, I know I've been indoctrinated to start drooling when you see grill marks. The truth is that grill marks mean much of the meat's potential has been lost." Could you explain?

Meathead: Yes. There's a chemical reaction that happens when energy in the form of heat interacts with proteins and amino acids, which are a major component of meat. When meat changes due to heat, we call it the Maillard reaction. It was named after a scientist named Maillard who first described it. It's just the browning reaction, is what happens when you brown bread, when you brown meat, roast coffee, chocolate beans. The Maillard reaction is what turns the surface of the meat brown. Now, if you put your meat down on grill grates, metal is a really strong source of conduction energy.

There's three types of energy on a grill. Conduction is one of them. That high energy from the metal grill grates brands the surface of the meat with stripes. We call those grill marks. That Maillard reaction creates new flavors, which we really like. We love the flavor of browned meat. You have this grill grid pattern on the surface of the meat. In between the grill marks, you have tan meat that hasn't been turned brown by Maillard. The better-flavored meat is going to be browned all over. You go to a great steakhouse, and you won't see great grill marks on a steak. It'll be browned edge to edge. we talk about in The Meathead Method, how to do that.

Alison Stewart: We're talking about a new cookbook from barbecue hall of famer Meathead, exploring the science behind barbecuing, grilling, and outdoor cooking. It's called The Meathead Method. Hey, listeners, do you want to get on this conversation? Do you have a question for Meathead? Our number is 212-433-WNYC, 212-433-9692, or maybe you just want to tell us what you're cooking on Memorial Day? What do you plan to put on the barbecue? Our phone number is 212-433-WNYC, 212-433-9692. Our phone lines are open to callers. You mentioned your dad. Is it true that your dad was a food scientist at Cornell?

Meathead: He was a food technologist. I'm not quite sure of the difference, but he was a food technology major at NYU, and he later opened a butcher shop with my uncle, that promptly went bankrupt. Then he had a restaurant, promptly went bankrupt. Then he became a stockbroker and made a lot of money. He cooked out back, and I love to hang out with him. His specialty was flank steak, and it was fun to-- "Oh, they love the smell of grilling flank steak." He might have let me have a sip of beer every now and then, which might have piqued my interest, but he was my inspiration.

Alison Stewart: For people my age, Meathead means Michael Stivic from All in the Family.

Meathead: That's right. He also is the one that gave me the name Meathead. You don't look that old. There was in, I think the '70s, a TV show, All in the Family.

Alison Stewart: All in the Family.

Meathead: Michael Stivic was one of the characters. He was played by Rob Reiner and Archie Bunker, the star of the show called Michael Meathead. They have that. That was because they differed politically. My dad and I differed politically, but he wasn't a bigot like Archie. My dad started calling me Meathead. In the '90s, when I first got online on AOL, I ran the AOL food and drink department for many years.

Alison Stewart: Oh, interesting.

Meathead: Oh, yes, AOL was like Facebook in those days. They dominated the media. We had a huge section. I brought Julia Child on. I was the first one to bring Julia online. Yes, we did a chat with her and her assistant. Her assistant did all the typing, but dad called me Meathead. When I got online, you need an avatar, you need a name. Meathead stuck.

Alison Stewart: We got a question here for you. It says, when trimming a 15-pound brisket, how much fat should I leave intact?

Meathead: Ah, great question. First of all, you got to understand that meat is about 75% water. Fat is oil. Oil and water don't mix. If you leave the fat-- and a brisket, which can be large, can be 18 pounds, often has a half inch to a full inch of fat on one side. That fat cap will melt partially, but it can't penetrate into the meat. The fat that flavors the meat is the marbling, the fat that is woven throughout the meat fibers inside. Fat caps cannot get into the meat because oil and water don't mix. If you leave it on, like some people do, and you cook that gorgeous brisket and you slice it perfectly and you put it on the table with a half-inch of fat on it. Then your spice rub is on top of the fat. What happens?

Your guests are going to cut all that fat off, and there goes your spice rub. I recommend you remove all of the fat down to maybe an eighth or a quarter of an inch at most. A quarter of an inch, during the cook process, it'll shrink down to maybe an eighth inch, and people will eat an eighth inch of fat along with their meat. Then they get your spices and everything. The fat really doesn't do anything for you. I like to cut it off, I freeze it and I save it. When I make hamburgers-- and if you want, we can talk about burgers. When I make hamburgers, I sometimes blend that into my hamburger blend.

Alison Stewart: Oh, let's talk burgers. Explain.

Meathead: Okay. All the cookbooks tell you, and, by the way, we can do an hour of me starting my sentences with "all the cookbooks tell you". All the cookbooks tell you never press the burger with a spatula because that squeezes out all the juices. Your typical hamburger is 80% lean, 20% fat. If you squeeze a hamburger with a spatula, a lot of the juices will run out. The good news is, is when they hit the coals or the flavor bars from a gas grill, they will vaporize and come back up and they add flavor to the meat.

If you do that, especially on an 80/20 blend, you'll end up with a hockey puck. It'll dry it out. How do you get that flavor from the vaporization and not dry it out? You move it to 70/30. You ask your butcher, give me a burger grind that's 70% lean, 30% fat. Now, look, and I know that's a lot of fat, but burgers aren't diet food, and you knew that anyhow. You're not going to eat them every night. If you kick it up to 70/30, then you can smash it gently, get that fat, the juices, the spices to hit the hot flame and the hot metal, come back up on the meat. Flavor the meat, and it'll still be juicy.

Alison Stewart: Let's talk to Al, who's calling in from Hudson, New York. Hey, Al, you are on the air.

Al: Hey, what's up? Big fan of both of you. We're doing a chicken fry this weekend, and I have a couple different methods going. Brining. I'm doing a pickle juice brine, and then just a classic buttermilk. I would love to hear your thoughts on different brines. Then what you do for the dredge to get an extra crispy chicken.

Meathead: Funny, I just last night did a live video feed for-- can I mention Milk Street?

Alison Stewart: Sure. Yes. They've been on [unintelligible 00:13:32], yes.

Meathead: [crosstalk] for Kimball's Milk Street last night and I did fried chicken. First of all, fried chicken is an outdoor cooking experience. You cook it indoors on your stovetop. This is why nobody cooks fried chicken at home. You do it on your stovetop, it spatters all over the stovetop, spatters all over the counter, gets on the floor, sets off the smoke alarm, stinks up the house for a day. Get yourself a Dutch oven, take it outside. If you've got a gas grill, it's easy to control the temperature. Turn one burner on the gas grill on high, put the Dutch oven there, pour 2 inches of oil in it, get it up to 350 to 375. That's your magic number for deep frying almost anything. Donuts, chicken.

350 to 375, and fry your chicken on a gas grill or a charcoal grill. Gas is easier. You fry it in the oil there. When it's done, you take it off and set it on the other side of the grill where the burners are off. It'll just sit there and stay warm and drip dry. Now, about dredge put me in the pickle juice category. That's what I did last night. Pickle juice is water, oil-- Pardon me, water, vinegar, and salt. Salt is the magic rock. We'll talk about salt in a minute. Salt is the magic rock and it's different than any of the spice you have on the rack. I want to teach about salt here if I may.

You want to do brining and you can brine it, you can dry brine it, which is to sprinkle salt on it the day before. You can wet brine it, which is to put it in a blend of water and salt in the ratios I have on my website or in my book, AmazingRibs.com is the website. Or you can use a pickle brine, which is pretty close to the right ratio of salt to water. I don't use egg or buttermilk or anything like that because I like my fried chicken to be golden. When I use egg or buttermilk, it tends to come out brown.

You want to take it up to about 160 in the oil and at that temperature, it'll brown the crust. As far as the dredge is concerned, golly, just plain old flour is fine. I go with a flour and cornstarch mix. I know some people that are really wedded with potato starch. I mean, there's recipes on the Internet for the Korean fried chicken, which uses its own blends. The pros even have a compound, I forget the name of it, that really enhances crispiness. Drop me an email meathead@amazingribs.com, and I'll tell you the name of this product. Okay. Can we do salt?

Alison Stewart: Yes, sure.

Meathead: Okay. Salt is one of the most important things you can work with. Yes, I know your doctor wants you to go light on salt, but I'm going to give you a rule of thumb that won't get you in trouble with your doc. Salt is the magic rock. It's different than anything else that you have in your cupboard. It's two atoms, one atom of sodium, one atom of chloride. When they get wet, they get vibrating, and it's called ionization. They can move deep into the meat to the center. When they get there, they screw around with the proteins.

Protein is the most complex molecule known to man. It's wound and twisted and bound, and it's got holes and cracks and crevices. When it gets fooled up, fooled around, you got Alzheimer's. In meat, the salt will mess with it and helps it hold on to moisture. Aha. Hold on to moisture. We want that. It also amplifies flavor. Aha. We like that, too, but it doesn't alter the flavor. Garlic amplifies flavor, but it alters the flavor. All the other stuff that you want to put on the chicken, the molecules are too large. Sugar is 23 atoms. Salt is 2 atoms.

Sugar, garlic, onion, black pepper, all the stuff that you like to put on your chicken or your turkey can't get past the surface. The surface may look smooth, but there's actually a lot of little tiny cracks, crevices, and pores that it can get into, but they're not very deep. These spices and rubs can only penetrate about an eighth of an inch. If you don't believe me, go out and get a turkey breast, cover it with every spice that you have in the house, cook it up, cut it in half, and take a core sample. It tastes like turkey. You won't taste the garlic. You won't taste the pepper.

People who do their Thanksgiving turkey in a giant tub of apple juice with a bottle of everything in the space. It's wasting money, wasted time. If you want those flavors, you just sprinkle them on the surface before cooking, any time. The salt takes time to do its magic, so you got to get it on early. For a steak, do it a couple of hours ahead. Same thing for a chicken. For a turkey or a brisket, you might want to do it overnight, but it takes time. Salt is magic. The rest of the stuff just sits on the surface. You can put it on anytime you want.

Alison Stewart: I got a question here. It says, I'm lucky to have a Brooklyn garden space. What kind of grill do you recommend?

Meathead: Ah, I'm lucky, too. I live in a suburb of Chicago, and my wife, who is a PhD microbiologist and was head of food safety at the FDA for many years, retired in 2018. If you eat at our house, you won't get sick, I promise. She's taught me an awful lot about food safety.

Alison Stewart: I'm sure.

Meathead: Awful lot of-- Food safety permeates everything I write. She's a master gardener now, and she actually has a certificate. Come August, next month, or no, two months. I mean, I go practically meatless. I have a marvelous recipe on my website for eggplant parmesan. The book has a caponata recipe that's really good.

Alison Stewart: Oh, you like roasted tomatoes a lot, too.

Meathead: Backyard-- Oh, let's talk about the smoked cherry tomatoes, because that's killer, and anybody can do that in a pot. The question about what kind of grill really comes down to how many people you're cooking and what type of cooking. I think charcoal is most versatile. There's a rumor, rumor. It's a belief, unfounded, that charcoal is better flavor than propane. The big difference there is that charcoal produces more infrared radiation than propane. When I said there were three types of energy on a grill, one was conduction. That's what you get from the hot metal. Another is infrared radiation. That's what you get from glowing coals or flame, from propane.

That's a very intense type of radiation. Go out in your backyard on a sunny day, and you know there's ultraviolet. You know what's more? Infrared. You're getting a lot of infrared in your backyard, beating on the back of your neck. Now, you can step away from the infrared by getting into the shade, and you can do the same thing on your grill. You want to set up a grill in two zones. You want a hot zone where all the charcoal is piled up on one side, but nothing on the other, or a gas grill where the burner on one side is on but not on the other. This gives you temperature control.

You can cook over infrared, you can cook over conduction from the hot metal, or you can move it off to the other side where there is no energy and cook with convection airflow, gentle warming airflow. We can talk a little bit more, if time permits, about how you use that convection airflow because it's crucial. Back to your question. Gas grills are dead simple. You fire them up. If you're going to go with a gas grill, try to get one of the new modern ones that has what they call a sear burner or an infrared burner.

Now, it may cost a bit more, but they generate extra infrared and they can make-- I've got one that has a lot of infrared and I'll tell you, I'll cook a steak on it. You can't tell if it was on a gas or charcoal. Bottom line, all the great steakhouses everywhere, Peter Luger's, anywhere in New York, all the great steakhouses cook over gas.

Alison Stewart: My guest is Meathead. We're talking about barbecuing, grilling, outdoor cooking, and the science behind it. His new book is The Meathead Method. Hey, Trey is calling us from Rockland County. Hey, Trey, thank you so much for calling All Of It.

Trey: Oh, thank you, Alison. You always keep me reading, so I appreciate you.

Alison Stewart: Appreciate that.

Trey: To your guest. He kind of just answered my question a little bit because I'm practicing. I'm a practicing griller. Okay. I prefer to cook outside. I don't know if I'm that great at it yet. Okay. I'm doing things with the charcoal, but I'm never sure what I'm doing. You kind of answered it because I've been piling-- I've just been piling the charcoal in there, man.

Meathead: Let's go back to this two zone concept I was talking about, because if you master this, you're way ahead of the game. Of course, I would say if you really want to learn, you should buy my book. That's up to you. You can learn a lot from my website, which is free. 2,000 pages of free content over there. When you set up in two zones, you have a hot side, infrared side, and a non hot side, convection airflow side. You want to start most of your food away from the infrared. It's really high intensity.

You want to start on the other side where it's going to gently warm. Now it'll take longer to cook, but it'll-- When you apply heat to muscle fibers, they contract and they squeeze out their juices. You get dry meat, dial back the temperature. I mean, we guys, we want to go out there. "Oh, going to give her all she's got, Scotty." You don't want to give her all she's got, Scotty. You want to dial it back. You want to go gentle on the meat, warm it gently.

If you cook, let's say we're going to do a steak. There are two different kinds of steaks. There's skinny steaks and thick steaks. This is also crucial, cooking indoors or outdoors. The thickness of the food you're cooking is what controls how long it cooks, because it takes time for the energy to get from the outside to the center, and the center has to be cooked to a safe and delicious temperature. A thick steak takes longer than a skinny steak.

A skinny steak, 1 inch grocery store steak, right off the shelf, hot and fast. You'll get a good sear on the outside and it'll cook in the center. A big, thick steak, if you cook it hot and fast, you risk burning the outside before the center is cooked. What you do is you start it on the indirect side where it can warm gently edge to edge. Then when you get it-- A perfect steak is most tender, most juicy, at 130 to 135 Fahrenheit. Now, we know this because there are machines that can put pressure on a steak and measure how much energy it takes to cut through the surface.

A Warner-Bratzler machine that measures the resistance of the steak. We have machines that measure the moisture. Most moist, most tender at medium rare, 130 to 135. That's your target temperature for a great steak, and lamb chop, and pork chop. If you're going to cook a thick steak, you start it on the indirect side and you take it up to about 120, 125. Oh, interlude, interlude. You've got to have a good instant read thermometer.

Alison Stewart: Yes, you do.

Meathead: They cost $30 or less. Again, the guy's like, "I don't need a thermometer. That's for sissies." No, it's not for sissies. It's for good cooks. Nothing, not even a sharp knife, is more important than having a good thermometer.

Alison Stewart: I like you beat your chest when you talk about men being men.

Meathead: There are a lot of knuckle draggers in the barbecue world. You got to have a good instant read thermometer. You can get one for $30. I've got a electrical engineer on our website who tests thermometers. Go look at his database. Pick one that fits your budget. We don't sell them. We'll just send you off to where you can buy them. You must have a-- You're going to use your instant-read thermometer.

When that steak hits about 120, 125, it's not quite done yet, you're going to lift the lid and move it directly over the hot charcoal, the infrared zone, where it's pounding it now on one side with intense energy. That's going to build your crust. That's going to make it really dark brown. You're going to get that Maillard reaction that we want, which is a lot of flavor. Guess what? Again, all the cookbooks say this, not to flip the food often. That's wrong. Flip, flip, flip. I want you to flip every minute because what happens is, is when it's sitting over infrared, that underside is getting loaded up with energy. It's like a battery, it's like a capacitor and it's loaded up with energy from the fire.

Now you flip it over and what happens? That energy bleeds off into the atmosphere instead of going down into the meat and overcooking the meat. That's why you lift the lid. You're going to flip, flip, flip. Keep the energy on the surface and coming off into the atmosphere, and you've got a restaurant-grade steak. One more trick-

Alison Stewart: I can't--

Meathead: -try to get USDA prime or choice when you're shopping. Those are the best quality.

Alison Stewart: We ran out of time. I would love to have you back if that's okay.

Meathead: I'd love to come back.

Alison Stewart: That would be good.

Meathead: I am a devotee of PBS, NPR. I subscribe, have for many years. It's an honor to be on there. If they take away your money, I'll do my job. I'll support you.

Alison Stewart: Thank you so much. We'll have you back. Meathead. The name of the book is The Meathead Method. Have a great day.

Meathead: You, too. Thank you.