The Legacy of the Late Bobby Weir and the Grateful Dead

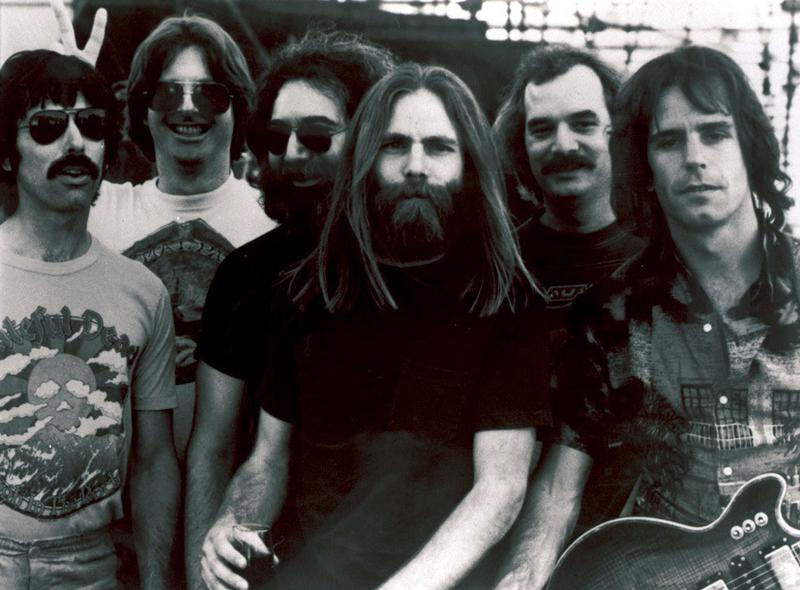

( AP Photo/File )

Alison Stewart: This is All Of It on WNYC. I'm Alison Stewart. We've just been listening to my interview with Bobby Weir, the Grateful Dead co-founder who passed away last week at the age of 78. Weir was at the helm of one of the most dedicated fan bases in music history. Now we want to open up the phone lines to the fans. Are you a Deadhead? How long have you been a fan of the band? How many concerts have you seen? What's your pick for their best show? What did their music mean to you? Our Phone number is 212-433-9692. 212-433-WNYC. Call in and text your thoughts and memories. Maybe you have a memory of Bob Weir's other music projects: The Other Ones, the Dead, Kingfish.

Our number is 212-433-WNYC. As your calls come in, I'm joined by David Browne, a Rolling Stone contributing writer who's also the author of So Many Roads: The Life and Times of the Grateful Dead. It is good to see you.

David Browne: Great to be here, Alison.

Alison Stewart: Bob Weir was the youngest member of the Dead. He was only a teenager when the band formed. What kind of music was young Bobby Weir into?

David Browne: What's really interesting about the Dead was the magic of the Dead was that each guy in that band came from a completely different space musically. Phil Lesh was into kind of classical, experimental music, and Jerry was into early rock and roll, bluegrass. Bob came from this country folk kind of thing. He brought that element into it. Bill Kreutzmann was a jazz guy, so it was really fascinating. Bob, his taste expanded much after that. He brought a little bit of that earthy quality to the band early on.

Alison Stewart: The legend is that he was in the band, and then he was fired. Is that true?

David Browne: This is true.

[laughter]

Alison Stewart: Okay. Tell me more.

David Browne: I have heard the tape of that meeting.

Alison Stewart: Oh, tell us more.

David Browne: The meeting actually was in 1968. There was a band meeting. Basically, Jerry Garcia and Phil Lesh were not happy with him, and Ron 'Pigpen' McKernan, who was also in the band, they felt like they weren't keeping up with the band. This is when the Dead was really starting to move from being a cover band, R&B, blues, to more jammy, experimental. They were stretching out. Bob was known as the spacey kid; he wasn't keeping up. He had that reputation. He was eating macrobiotic stuff, being kind of spacey.

It wasn't a direct firing. It was like, "Well, we're not sure you're right now," or that kind of thing. And they were like. There were pauses. It was almost like that episode of Seinfeld where George Costanza is fired and he comes back to work, and he's like, "You didn't fire me, did you?"

They tried playing without him. They realized it wasn't good. The next thing you know, he just was there again, and they picked up. That was a really important moment. He was on the cusp of losing his gig there.

Alison Stewart: Why did he become so core to the group after being nearly let go?

David Browne: Well, I think, first of all, he was more of a frontman. It was funny, when the Dead in the '80s had that Touch of Grey moment, the head of one of the big, big honchos at their record company went to see them and complained out loud. When Jerry would take guitar solos, he would never showboat. He would never walk to the front of the stage and do that thing. He would just stand there, and they would complain. Whereas Bob, especially during that time, was more than happy to run around on stage.

He brought that energy. His guitar playing was a great compliment to Jerry. It wasn't just typical rhythm guitar playing. He brought another voice and perspective. His voice and his songs were very different from Jerry's and occasionally Phil Lesh's. I think that he had that more romantic kind of quality to his song. Again, it was another important element in that band.

Alison Stewart: I'm talking to music writer David Browne. His books include So Many Roads: The Life and Times of the Grateful Dead. We're taking your calls. Tell us about your relationship with the Grateful Dead and Bob Weir. Our Phone number is 212-433-9692, 212-433-WNYC. What's your favorite song? What's your favorite concert? Let's talk to Angelica, who's calling in from Monroe Township. Hi, Angelica. Thanks for making the time to call All Of It.

Angelica: Thank you. I remember when I was 14 years old, my boyfriend's father dropped us off at Englishtown Raceway Park. It was all based on the Dead being there, and it was so awesome. Terrapin Station was out at that time. Sly & The Family Stone were there. There was so many people there. It was great. It was a big camping fest. It was just great.

Alison Stewart: What made you continue to be a Deadhead?

Angelica: I guess the lyrics, the words.

Alison Stewart: That's what you need. It's interesting, her saying that she got into it when she was just 14.

David Browne: Yes, I think a lot of us did. I was around that age when I first heard their music, too. That Englishtown show in '77 was so important because that was right when Terrapin Station came out. That attracted a couple of hundred thousand people. Up until that point, the Dead were popular—they didn't play Madison Square Garden until a couple of years after that—so there was that period when people were like, "Well, they have a following, and they seem like they have fans," but when things like that happened-- They were headlining this whole day thing in oppressive heat. You remember that. It was incredibly hot. There were so many people who were trying to get in that, remember, they circled the stage with campers, as an unofficial gate around things. It was an important musical show, but also, just as a cultural impact, it really was important.

Alison Stewart: How did Bobby Weir carry on the mantle of the Grateful Dead after Jerry Garcia died?

David Browne: Again, as sort of being the front man of the group, he was the one who really had to ramp up his role, in a way. They brought in various people to play guitar with them over the years, whenever they would reunite, like Warren Haynes or Trey Anastasio, and so forth, but the focus really kind of shifted to Bob. It was interesting. He would often sing the songs that Jerry sang, like Touch of Grey. He grew a beard, which he kind of didn't really have. He had a Jerry-like vibe to him in a way.

More seriously, I remember interviewing him at one point, and he would talk with reverence about the band, its mission, its music, and what it meant to the fans. The other guys in the group would be kind of joking and wiseacre-y about things. They took it seriously, but Bob had this seriousness. It came through in that interview you guys just ran, too. It was a serious obligation that was now on him to continue this and to extend it, which he did right up until last fall.

Alison Stewart: Let's talk to Tony, who's calling from Freeport, Maine. Hi, Tony, thanks for calling.

Tony DiMarco: Hi. Thanks for taking my call. You asked a lot of questions about some of us old Deadheads and our interest in the music. I just wanted to mention that I have a radio show on WBOR, it's a Bowdoin College radio station. It's called Dead Air. My mission really is to promote this 300-year legacy that Bob had talked about. Try to get the next generation interested in the music. To some degree, it's working. My kids are interested, and stepkids.

If you think about all of the cover bands that are playing the Grateful Dead across the country-- I have a friend who pointed out once as we were listening to Dark Star Orchestra, just a couple weeks ago in Portland, Maine, that probably every night of the year there's at least one cover band playing the Grateful Dead across the country. There aren't many bands where you could say that's true.

Alison Stewart: That's true. Thanks for calling in. Let's talk to Mark in Staten Island. Hey, Mark, thanks for calling All Of It.

Mark: Hey. I got two different cross-country trips associated with Bob Weir. Most recently, I drove from Spokane, Washington, back to New York. After holding off for a year on the serious subscriptions that came with my car, I took it up in part so I could use the Grateful Dead channel and Little Steven as driving music. In 1984, I was on my way west, and I had gotten from Santa Monica to Trancas on a hitchhiking attempt on a Saturday. A couple at a restaurant offered to take me to a Bobby and the Midnites show on [unintelligible 00:10:16] that maybe I would meet somebody who was on their way up the coast to Santa Cruz. Unfortunately, that didn't happen, and I slept on the beach that night.

In the course of the year in Santa Cruz in 1984, I saw the Grateful Dead eight times. You really got to hear the Woodstock show at some point. Pigpen is essentially pulling Weir out of an acid haze and using him as a musical instrument. It's beautiful.

Alison Stewart: Thank you so much for calling in for that descriptive description there.

[laughter]

Alison Stewart: Bob was part of so many other bands: RatDog, Wolf Bros, that was mentioned, the Dead, Dead & Company. His many other projects, David, what did it demonstrate about him as an artist?

David Browne: I think it demonstrated that he was eager to make his own stamp on things. He was briefly in a band called Kingfish in the mid-'70s, where he got to play with other musicians and try out some of his own songs without them. I remember going to see him with the Wolf Bros at the Beacon Theatre a few years ago. It was just Bob on guitar for most of the show. It's just like a trio. You really got to hear his musicianship, in a way, that it highlighted the very idiosyncratic, unconventional way he had of playing guitar, which was not quite lead and not quite rhythm. It was very interesting syncopation. I think projects like that allowed him to stretch out a bit more like that and show what he brought to the scene.

Alison Stewart: We are talking to David Browne. He wrote the book So Many Roads: The Life and Times of the Grateful Dead. We're taking your calls. We'll have more after a quick break. This is All Of It.

[music]

Alison Stewart: You're listening to All Of It on WNYC. I'm Alison Stewart. My guest is music writer David Browne. His books include So Many Roads: The Life and Times of the Grateful Dead. We are taking your calls. Tell us about your relationship with the Grateful Dead and Bobby Weir. What's your favorite song? What's your favorite concert? 212-433-9692, 212-433-WNYC. We should play some music. You wanted to play Looks Like Rain. David, why did you want us to play this song?

David Browne: This is a song from Bob's first solo album, Ace, back in '72. It's a beautiful, haunting song with lyrics by John Perry Barlow, his longtime collaborator. It's a great example of what Weir brought to the Dead. I think most people, when they think of the Dead, think, "Oh, it's Jerry's Band," and think of his voice, especially if you're not a Deadhead. Bob brought this beautiful country folk sensibility and much more direct, emotional performances and lyrics to the band. You started with Sugar Magnolia. That's the song of his that hit me first, and established his own identity in the band. I think something like Looks Like Rain, which has the Dead playing behind him, by the way, is a great example of a whole other musical spectrum that he brought to them.

Alison Stewart: Let's hear it.

[MUSIC - Grateful Dead: Looks Like Rain]

Alison Stewart: Let's talk to Barbara in Woodbury. Hey, Barbara, thanks for calling in.

Barbara: Hi. Thanks for taking my call. Just wanted to say that Bob was such a special human being. Not just the way he touched people with his music, but with his activism. He was pro-animal rights, he was a vegetarian, and was the love of my life, my soulmate, in 2008. He died September 3rd, 2020, from cancer. Bob was a huge part of our lives. We traveled all over the place to see Bob and RatDog. We went to Red Rocks. We went to Kentucky. We went to Indiana. We went to many places to see Bob. Bob was just woven into the fabric of my life with my soulmate. Having Bob die now is almost like reliving-- his name was Bob, too. My Bob's dying.

Bob was just such a special human being. I got him to meet him a few times. Just gracious, I was just like an idiot fan. Just a wonderful human being, like they say. My landscape is empty now that he's gone. I feel.

Alison Stewart: Barbara, thank you so much for calling in and for your candor. You were sharing, Dave, that backstage you met him and it was different than what people saw him as the woo-woo Bobby Weir, right?

[laughter]

David Browne: As we talked earlier, he had this reputation going back to his teen years as being the spacey, younger member of the band. The other band members would bust his chops a lot, including about his shorts. They would all make jokes about that.

Alison Stewart: We know about the shorts. Everybody at VH1, you know about the shorts.

David Browne: [laughs] I remember back in 2009, the four core members and Warren Haynes reunited for a tour as the Dead. They did three shows in one day here in New York City to warm up for it. I was just tagging along with them the whole day. Bob was very nice, but he was kind of serious, a little somber, little soul. The other guys were joking around, wisecracking, and trying to rekindle that vibe they had between them. They did a show at a club downtown. They did the Gramercy Theatre, and then they did Roselands with very few breaks. I remember Bob was like, "It's like a tour with cab rides."

I remember at the end of the very last show, I was standing with him and Mickey Hart. Mickey, in his usual effusive way, was like, "Oh, it sounds great. Woo, woo, we're back." Bob was just nodding, and he said, "The arrangements could use some work." He was listening, even though you might think watching him on stage that he seemed a little floating around or whatever, or not zeroing in. He was listening to every little thing. It was really interesting to hear that. It brought Mickey down a little bit, I think. "Oh, okay, Bob doesn't think it's quite right yet."

Alison Stewart: That's interesting. Let's talk to Terry in Glen Rock. Hi, Terry. Thanks for calling All Of It.

Terry: Hey, Alison, thanks to you and Dave for doing this. I think about Bobby and the fact that he was 16 when he joined the band. I was 16 when I first saw them. About 100 shows over 10 years, and then all the clone wars with all the iterations after that. Had the pleasure of going to the concourse at Jazz Fest, Fair Grounds to hear an interview. Bobby and about 20 people, and someone had the foresight to ask him if he still touched in with psychedelics. He mentioned the fact that he just finished doing Austin City Limits, and he took some mushrooms that day, and his guitar neck turned into a snake. He mentioned a line that I won't forget. He said, "If you look at the video of that Austin City Limits show, you'll see moments of abject terror." I just thought it was really cool to learn that they still dabbled in some of the things that maybe the audience were doing at that time.

Alison Stewart: That was well put. Thank you very much for putting it that way.

David Browne: There were drugs associated with the Dead. That's not true.

Alison Stewart: Something like that, I don't know.

David Browne: Not true.

Alison Stewart: You picked another song, David, for us to play. Hell in a Bucket. Why this song?

David Browne: This is a song from their In the Dark album in 1987. I think it captures some of that cultish energy that Bob could bring to the Dead, not just on stage, but sometimes in the studio as well. He gets this song and One More Saturday Night. He had these moments where he got them to rock out, maybe in a more traditional way. The lyrics are really funny. Again with his collaborator Barlow, with bikers and breakups. It's a feisty song that really, again, shows another emotional musical element that Bob brought to the band.

Alison Stewart: Here's Hell in a Bucket.

[MUSIC - Grateful Dead: Hell in a Bucket]

Alison Stewart: Hey, Josh. Is calling in from Brooklyn. What say you, Josh?

Josh: Well, first, I'd like to thank you so much for dedicating this time to him. It's obvious from listening to everybody talk about Bobby Weir, how much he moved everybody. When I was about 14 or 15, just glancingly into the Dead, somebody grabbed me in the hallway in high school, I was in Cleveland. "We're driving to Detroit to see the Dead, and you're coming." We did a few trips like that. I saw them.

What I told the screener, and what I'd like to share with people broadly is that just from listening to their albums, in particular the live ones, like Europe '72 and the Skull & Roses album, is my ear fell toward what Bob was doing in the background. These subtle things, these connecting chords and offbeat rhythms, and just really interesting things. It taught my ear to listen to things that weren't in the front in music, and pay attention to them. From there, I started listening to Lesh and the interesting things he was doing. From there, I would listen to the jazz that my father would give me, listen to the different parts, and later classical music. I really credit Weir's subtle playing with teaching me to listen carefully and thoughtfully to music.

Alison Stewart: Thank you so much for calling. Did you want to respond to that?

David Browne: I love the subtle playing aspect of it. I did a recent playlist of Bob's 10 best songs. It was in The New York Times, and boy, it was really hard narrowing it down to 10. It was another reminder to me of how many great songs he had. Off the top of my head, I had 25 that he sang with the Dead. There was one that I left off for space, called Weather Report Suite that's on the Wake of the Flood album. It's this ambitious three-part Prague folk thing. The subtle thing brings out. It has all these different sections. His playing and Jerry's playing are woven in and out of each other. It's a really beautiful piece of music that, unfortunately, I couldn't have room for the list, but that comment made me think about it.

Alison Stewart: You got it on the air, Adam, you got 30 seconds. Go.

Adam: All right. I grew up in Michigan listening to Rush. When I got out west to college, my friends took me up to see the Dead at Shoreline Amphitheatre. The first show I saw, Bobby played Saint of Circumstance, and I knew they were a rock and roll band. That was the first song I heard that rocked. I've been a follower ever since. I saw 97 shows with Jerry still alive. It's been a--