The Gods of New York' Spotlights the 80s

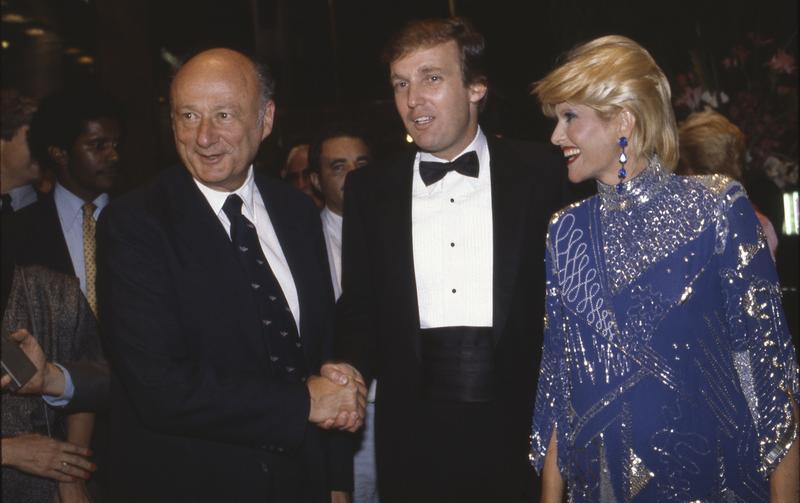

( Photo by Sonia Moskowitz/Getty Images )

[MUSIC - Luscious Jackson: Citysong]

Alison Stewart: This is All Of It. I'm Alison Stewart, live from the WNYC Studios in SoHo. Thank you for spending part of your day with us. I'm really grateful that you're here. Today, we're going to look ahead to the school year, and we're also looking ahead to a few projects involved in the New York City public schools. We'll also talk about the music of Marc Bolan with the filmmakers behind a new documentary about his music and the making of a T. Rex tribute album. We'll speak to artist and reverend, Joyce McDonald, about her testimonial sculpture, which reflects on her activism and her life as an AIDS survivor. That's our plan, so let's get this started with a trip back to New York in the late 1980s.

[MUSIC - Public Enemy: Fight the Power]

1989, the number another summer (get down)

Sound of the funky drummer

Music hitting your heart 'cause I know you got soul

(Brothers and sisters, hey)

Listen if you're missing y'all

Swinging while I'm singing

Giving whatcha getting

Knowing what I know

While the Black bands sweating

And the rhythm rhymes rolling

Got to give us what we want

Gotta give us what we need

Our freedom of speech is freedom or death

We got to fight the powers that be

Lemme hear you say

Fight the power

Fight the power

Fight the power

Fight the power

Fight the power

Fight the power

Alison Stewart: It is hard to overstate how much the spirit of Public Enemy's Fight the Power explained New York in the late 1980s. You may remember it from Spike Lee's film Do the Right Thing, released in 1989. Both the song and the movie captured the social climate and intense racial division of the city at that time. In his new book, New York Times Magazine staff writer Jonathan Mahler makes the case for those four years, 1986 to 1990, that they were crucial for forming the modern New York we know today.

If you were there, you know Wall Street's boom and bust, the AIDS crisis, the crack epidemic, the rise of hip-hop, the major figures, mostly men, who played a big part in shaping the late 1980s. You know them. Koch, Trump, Giuliani, Dinkins, Sharpton, and Kramer. Then there were the legal cases that dominated the New York conversation. Howard Beach, Bernie Goetz, Yusef Hawkins, and the Preppy murder trial. The flames of which were fanned by the powerful daily tabloids and their shrieking headlines. The book is called The Gods of New York: Egotists, Idealists, Opportunists, and the Birth of the Modern City: 1986-1990. Jonathan Mahler is in studio right now. You might recognize him from his book Ladies and Gentlemen, the Bronx Is Burning. Welcome.

Jonathan Mahler: Thanks so much for having me. Nice to see you bobbing your head along to the Public Enemy.

Alison Stewart: I know. I'm so excited by this segment. I got to calm down. Let me calm down. First of all, how did you identify 1986 to 1990 as the years you wanted to concentrate on?

Jonathan Mahler: Yes. Well, narratively, they were convenient because they were Koch's last term as mayor. The story begins with his inauguration in 1986 and ends with him losing and, in fact, Dinkins being inaugurated in 1990. His last term forms the spine of the story. Beyond that, it was just a crazy four years where so much happened. You mentioned some of the events in the introduction. From the crack epidemic to the AIDS crisis to all of these iconic racial events from Howard Beach to Tawana Brawley and on and on, it's also the great Black Monday crash on Wall Street, which threw the city's finances upside down.

It was such just a crazily, eventful four years. It was also an important four years in determining the future of the city. It was really a year where there was a struggle for the identity of New York, and the years, I would say, when New York really made the transformation from being what it had once been, this great working-class city into a city really powered by Wall Street, by finance, by real estate. We're still living in that city today, so I also saw those four years as just being seminal for the identity of New York.

Alison Stewart: What happened during that period of time that you think has been misunderstood or overlooked?

Jonathan Mahler: I would say that I think that people take the city's current identity and current economic model, and this idea of New York being a city of rich and poor with a hollowed-out middle class. That is, people just take that city for granted and just assume that that's what New York always was. There was a starting point for this New York, and decisions were made that created this New York. I think it's important to identify that moment.

Then I would also just say additionally that people-- Well, just to take one example, Donald Trump. There's a misconception, I think, that Donald Trump was created by The Apprentice, that that was Donald Trump's crucible. I think that, really, you need to go back to 1980s New York, to the tabloid culture of New York. That was really Donald Trump's crucible. I think just to understand the political moment we've arrived at now, this is the best starting point.

Alison Stewart: Listeners, we want you to think back to the years 1986 to 1990. What did it feel like to live in New York then? What was the energy of the city like? What are your memories that you associate with that time period? Our phone number is 212-433-9692, 212-433-WNYC. Were you a supporter of Ed Koch? Did you vote for Dinkins? Did you follow any of the big stories at the time? Bernie Goetz, Tawana Brawley, the Central Park killers, the Preppy killer.

Were you a loyal reader of the tabloids like The Post or the Daily News? Did you participate in any AIDS or racial justice protests at that time? Give us a call. 212-433-9692, 212-433-WNYC. I was going to say this for the end of it, but it has been bothering me. Not bothering me. I've just been wondering about it. Can you think of one thing that happened during that time, it could be a small thing, it could be a big thing, that really leads to the biggest issue in the city, in my humble opinion, right now, which is income inequality?

Jonathan Mahler: Yes, I would say that there were decisions that were made really in large measure to get the city's economy moving again, right? We're talking about big tax breaks to real estate developers, big tax breaks to corporations to stay in the city rather than moving out of the city, which is what they were doing back in the dark days of the '70s. To me, those decisions, which were giving financial advantages and financial incentives to corporations and to real estate developers, was a very important specific policy decision that led to this widening income gap.

Alison Stewart: You touch on the 1970s in this book. What was important to know about the crisis of the '70s and how the city recovered that set the stage for the '80s?

Jonathan Mahler: Really, this book is the chapter after the '70s, the '80s, of course. What happened is that, in the '70s, the city was in despair. Its economy was wiped out. All the factories had closed, had left New York, deindustrialization over the course of the '60s and '70s. Everyone remembers the iconic images of New York from the '70s--

Alison Stewart: "Drop Dead."

Jonathan Mahler: Exactly, exactly. Ford to City: Drop Dead. The subway's covered in graffiti. You can think of movies like The Warriors or Taxi Driver. What happened in the '80s was that a whole new city was built on the ashes of that city. A city of skyscrapers, the city of Trump Tower. It was a story. The '80s was a story of the rebirth of New York and the renaissance of New York, but to call it a rebirth or a renaissance is obviously really reductive and, in fact, misleading because a lot of people were left out of this rebirth. The '70s set the stage for this rebirth, but it was very much a selective rebirth.

Alison Stewart: We're talking about locally, but how did Reaganomics factor in?

Jonathan Mahler: Yes, sure, so that was a big part of it as well. You had a theory of economic growth that was, "Look, if we cut taxes, if we deregulate the financial markets, that will get the capital flowing." That's, in fact, what Reagan did. The idea was that money would trickle down. Trickle-down economics was the idea, that that money will trickle down to the poor, the middle class, and the poorer. [chuckles] History has shown that that didn't work terribly well. Part of the city's decision to throw its lot in with Wall Street and with real estate was driven by the decisions coming out of Washington and by Reagan.

Alison Stewart: We're going to talk about them individually, but what was different about leaders at this time compared to earlier leaders?

Jonathan Mahler: I would say that there was a way in which the city was up for grabs in this moment. There was also something going on. An interesting thing was happening with the media, which was that a lot of the papers had shut down. New York still had these three big tabloids. The Post, the Daily News, and Newsday. They commanded a great deal of power and really drove the narrative in the city.

I think that leaders, whether we're talking about elected leaders like Ed Koch or unelected leaders like Al Sharpton or like Donald Trump, recognized that the city was up for grabs, the city was going through some kind of transformation, and that these tabloids were a great place to wield power to. If you could capture the tabloids, you could capture the city. I think that's this moment when we saw-- It's not a surprise that that's where Donald Trump learned how to control a story, how to basically grab hold of the public's attention.

Really, the attention economy is what we call it now. He recognized it even then, as did Al Sharpton and many others. That, I would say, is what distinguished these leaders. That's what enabled them to become such crazily outsized figures. I call them the gods of New York. It's obviously tongue-in-cheek. They're not Judeo-Christian gods. They're like Greek gods with New York as their Mount Olympus. That's what allowed them to become like gods.

Alison Stewart: It's interesting. We got a text here that says, "Steinbrenner and Trump doing whatever it took to appear in the New York Post."

Jonathan Mahler: Exactly.

Alison Stewart: Following up on what you said.

Jonathan Mahler: Yes.

Alison Stewart: This text says, "My dad used to work in the city, and I remember picking him up in Times Square. We used to not to know how even to react. I was so young. I usually broke out in laughter at the porn theaters everywhere. My kids cannot comprehend how seedy it was. It was crazy intriguing. Now, it is all gone." Let's talk to Jerry, who's calling in from Forest Hills. Hi, Jerry. Thanks for making the time to call All Of It.

Jerry: Hi, Alison. Thank you for having me on. I just wanted to say I love your show.

Alison Stewart: Thank you.

Jerry: 1986 to 1990 were critical years to me. Those are the years I was in high school. I went to high school on the Lower East Side of Manhattan. I used to commute by train. I used to take the L train from Williamsburg at the time. I definitely saw a lot of change. With, obviously, Mayor Koch at the time, we had the closing of Greenpoint Hospital. That was also a critical time growing up. Of course, it was the AIDS. He was a big person involved in that as well. There was a lot of protests and a lot of things to really go against to what he was doing at the time. I saw a lot of change in the identity of New York City for sure.

Alison Stewart: Jerry, thanks so much for calling in. I'm speaking with Jonathan Mahler, staff writer for The New York Times Magazine and author of the new book The Gods of New York: Egotists, Idealists, Opportunists, and the Birth of the Modern City: 1986-1990. We're also hearing from you. What did it feel like to live in New York during those years? 212-433-9692, 212-433-WNYC. Let's talk about Mayor Koch. He used to say, "How am I doing? How am I doing?" What was his reputation as mayor?

Jonathan Mahler: Well, it's interesting, and I want to pick up on one thing that caller said. First, in terms of Koch, he was a beloved figure. It's almost hard to imagine now. He was an international celebrity. He was the mayor of New York, but he was just known as the mayor all over the world. He was really beloved in New York for years. During these particular years, 1986 to 1990, things turned. The city really turned on him. I think they began to see both the wages of the cost of the rebirth that he had presided over.

I think they began to feel like he was insensitive to a lot of the suffering and a lot of the problems the city was facing, which actually connects to the point the caller was making about that hospital closure. Part of the fallout from the '70s was the city had to cut costs, had to cut expenses, so they had to close hospitals. They had to cut back on healthcare spending. Of course, that happened just before the AIDS epidemic arrived. The city was totally ill-prepared to deal with the AIDS epidemic. Koch gets blamed by the activist community and by others, too, for having failed to deal with the AIDS crisis.

Alison Stewart: This text says, "Don't forget the huge Parking Violations Bureau scandal that Koch absurdly pretended to know nothing about." Would you explain?

Jonathan Mahler: Yes. Really, days into his third term, the Queens borough president at the time, a guy named Donald Manes, who's mostly forgotten by history, but was a big figure in New York at the time, is pulled over by some cops out by Shea Stadium. It looks like he's been stabbed. Big mystery for days. No one in the city knows. It's known as the Manes mystery. What happened to Donald Manes? He finally speaks a couple of days later, says, "I was mugged at knifepoint."

There were a lot of holes in his story, like his wallet hadn't been taken and a handful of other things. It turns out that he had tried to commit suicide because the FBI was on his trail for a massive kickback scheme in the Parking Violations Bureau. He was basically selling contracts to collect tickets for the city. Eventually, weeks later, after Giuliani, who was the US attorney at the time, is preparing to indict him, Manes does successfully kill himself.

Alison Stewart: Before we leave Ed Koch, did anyone care he was gay?

Jonathan Mahler: [laughs] Well, the gay community and Larry Kramer, in particular, the founder of ACT UP, was obsessed with outing Ed Koch. He certainly cared. He blamed Koch's inaction on AIDS, on the fact that Koch was in the closet. His contention was that Koch didn't want to draw attention to the gay community because it would just lead to accusations of him being gay. The amazing thing is, he denied it. He felt the need to come out and say, "I am not a homosexual."

Alison Stewart: This is Bess Myerson.

Jonathan Mahler: [chuckles] Exactly. He had his beard, who was a former Miss America, the first Jewish Miss America, Bess Myerson. He toted her around with him and made jokes about how there could be a marriage someday at Gracie Mansion, a wedding at Gracie Mansion. If you want to look for a silver lining in all this, it does say a lot about how much we as a culture have changed that, at the time, the mayor of New York felt that he could not be out. We've come a long way since then, at least in that sense. Yes, it's quite something.

Alison Stewart: We got a text that says, "Sadly, as a closeted gay man, Koch turned his back on the AIDS crisis."

Jonathan Mahler: Yes, exactly. I think that a lot of people felt that way, yes.

Alison Stewart: We are talking about the book The Gods of New York with Jonathan Mahler, staff writer for The New York Times Magazine. If you'd like to get in our conversation, you can give us a call. You can tell us what it felt like to live in New York City in the years of 1986 to 1980. Our number is 212-433-9692, 212-433-WNYC. We'll have more of your calls, and we'll have more with Jonathan after a quick break.

[music]

Alison Stewart: You're listening to All Of It on WNYC. I'm Alison Stewart. I'm speaking with Jonathan Mahler, staff writer at The New York Times Magazine and author of the new book The Gods of New York: Egotists, Idealists, Opportunists, and the Birth of the Modern City: 1986-1990. You said you were part-time in New York at that time?

Jonathan Mahler: Yes, yes, I was in college in Chicago. I would come back on vacation and check out all the craziness. Also, I was an avid reader of The Village Voice from afar. I was following everything that was happening here.

Alison Stewart: I moved here on 8/1/88. It's not a password anymore, but yes, that was my first day. Then I went to work at MTV next week, making $17,000 a year as an assistant.

Jonathan Mahler: Tompkins Square riots would have been right then.

Alison Stewart: Yes. Oh, my gosh. I had friends who lived. That was huge. One thing that I saw going around me as a kid making very little money was the boom of Wall Street, the luxury buildings, the office space. Wall Street was thriving. We were living in 400 square feet, three of us. Tell us a little bit about Wall Street in the '80s.

Jonathan Mahler: Yes. Really, what happened was that it was this amazing confluence of events. Both Reagan, who comes into office in 1980 as we were talking about a bit earlier, has this real free market. Milton Friedman, "Let's deregulate. Let's encourage as much trading activity and esoteric investment vehicles as we can," at the same time that technology is enabling traders to start trading bigger blocks of stock faster. Everything just starts to accelerate during these years. Wall Street starts going absolutely bonkers.

Investment firms start gobbling up all the empty office space that had been left by companies like Exxon, Coca-Cola, these old consumer goods and manufacturing companies that had once been in the city. New York gradually becomes a Wall Street city, and then all that money that Wall Street is generating and the bonuses, of course, drives the real estate market. New York, which had once been really a city of renters, starts to become a city with quite a few owners of multimillion-dollar apartment buildings, which, of course, opens a bigger hole in the heart of the class structure in New York.

Alison Stewart: Let's take a call. This is Dan from Astoria calling in. Hi, Dan, thanks for calling in.

Dan: How are you doing? This is Danny Dan calling in from Astoria.

Alison Stewart: Right.

Dan: Just calling with a reference back to 1990. I was 17 years old, just got my black belt in karate, and wanted to use it. I joined the New York Guardian Angels.

Jonathan Mahler: [laughs]

Dan: We patrolled Times Square. There was a martial arts supply store right on the middle of 42nd Street, where all teenagers got to, where you bought your nunchucks, your Chinese stars, your Bruce Lee books, all kinds of knives, all kinds of things that you cannot even get your hands on nowadays. We patrolled. I remember, Curtis back then was a great leader, good guy, and it's great to see him now in the race, and just wanted to end with that. I don't think we'll ever get those days back.

Alison Stewart: Dan, thanks for calling. Let's talk to Anthony from Brooklyn. Hi, Anthony, thank you so much for making time to call All Of It.

Anthony: Hi, I'd like to respond to Jonathan Mahler's comments about AIDS in New York City. AIDS was very different from COVID in that the disease was incredibly visible on the street. You could see clearly opportunistic infections that people were surviving, and the streets were like a war zone. Government neglect allowed for this expression of homophobic violence. It was a frightening time in New York City.

Alison Stewart: Yes, it was.

Anthony: Also, to respond to Jonathan's comment about Larry Kramer as the founder of ACT UP. ACT UP was formed out of a community response to Larry's talk at the gay and lesbian community center. Larry would occasionally show up and have a hissy fit.

[laughter]

Alison Stewart: I do want to explain, though, that in your book, you get into this in detail. I just wanted to explain, Anthony. Anthony, thank you so much for calling in. It does get deep into the book. We're going over the top. Let's talk to Edward in Manhattan. Hey, Edward, you have something that you say Koch did, which was really important.

Edward: It's the most important thing any mayor has ever done. He created the Pooper Scooper Law.

Jonathan Mahler: [laughs]

Edward: Prior to Ed Koch, walking in the city was disgusting. I won't use any words because we're on the radio. However, I see people today, people in their 20s, 30s, walking their dogs, picking up what the dogs have done. I say to them, "Have you ever heard of Mayor Koch?" They say, "No," so I tell them about Mayor Koch and the Pooper Scooper Law. He'll be remembered for that in my mind forever.

Alison Stewart: Thank you for the call. Did you want to respond to any of our callers who called in?

Jonathan Mahler: Yes, that's absolutely right. Regarding the Pooper Scooper Law, it had made a huge, huge difference. In terms of the AIDS crisis, absolutely. I think that one thing that happened with AIDS is it began in the gay community, but then it really spread into the homeless population as well, and really in New York's Black community also. Intravenous drug users. I think that other side of the AIDS crisis is overlooked. The caller was talking about people on the streets. I think that it was in-your-face in New York. It was very front and center, and yet there was, in many quarters, a real callousness towards it. I think, in particular, because it was largely affecting more marginal communities.

Alison Stewart: Let's talk about Benjamin Ward, New York City's first Black police commissioner. What was Ward facing at the time?

Jonathan Mahler: He had a very difficult job. He's an amazing figure who's been largely forgotten. I will say I got very lucky because I was going through his papers, and in his papers was an unpublished memoir that he had written.

Alison Stewart: Oh, my goodness.

Jonathan Mahler: Yes, it was an amazing trove of information, and really a candid accounting of what it was like to be the police commissioner of New York during these years. He came into office with hopes of-- At the time, there was a terrible problem with racist policing at that point, just like terrible police violence toward the Black community. It was something he wanted to address, but he pretty quickly found himself just like with a fire hose of crises, in particular, crack. He has limited resources. He's facing this massive drug epidemic, which was spike in crime and overtaxing the criminal justice system. He was really just barely able to keep his head above water.

Alison Stewart: Let's talk to Eddie from Milford. Hey, Eddie, thank you so much for making the time to call All Of It.

Eddie: Hi, Alison. You can hear me?

Alison Stewart: Yes, I hear you great.

Eddie: Great. Hi, yes, those years were so special. Some said that they were terrifying, but they were also joyous. I got to New York in 1984 at 22 years old to be an actor. The AIDS crisis hit. I'm gay. I was in Charles Busch's Vampire Lesbians of Sodom for a year off-Broadway in 1987, which was just absolutely joyous, except at the same time, friends were getting sick and dying, including a fellow cast member.

The next year, I tested HIV-positive in 1988 and gave up the acting. It was too much, with everything happening and the homophobia. I decided to go to law school. In 1990, I started law school after joining ACT UP because I wanted to be a civil rights attorney and a human rights attorney. Here I am, 37 years later, [chuckles] still alive, still HIV-positive, had quite a wonderful life. I also was at the Tompkins Square Park riots. I live in the East Village and, obviously, was part of the East Village arts scene working with Charles Busch.

Jonathan Mahler: Amazing.

Eddie: I'm really excited to read the book.

Jonathan Mahler: Yes, you lived it. [laughs]

Alison Stewart: He did live it. The riots in Tompkins Square. What started it? How did it end?

Jonathan Mahler: What started it was really that you had a lot of people. You had a large homeless population living in Tompkins Square. In a way, that wasn't really the core of the problem. The core of the problem was that it was where a lot of people would just gather and hang out and make noise and drink and do drugs. For many years, that had not been an issue because the Lower East Side and the East Village were pretty deserted.

What happened in the '80s is that neighborhood starts to get gentrified, and the yuppies start moving in, and people started complaining about the noise. The police decide that they are going to impose a curfew. They show up at Tompkins Square to impose this curfew at midnight on a Saturday night. There had been a warning. Local people knew. Local activists, local radicals knew. They came ready to protest and ready to get into it with the cops.

That's what happened. The park and the whole neighborhood around it turned into a crazy riot scene with literally cops on horseback chasing protesters around the neighborhood. Lots of people were injured. Lots of cops were also injured. It became a huge scandal. It really became a police scandal because it became clear that the police were far more violent than was appropriate.

Benjamin Ward, who we were talking about before, commissioned a report that laid all bare, where he really pretty courageously accused his own police department of real brutality. Of course, there were very few. Almost no one was prosecuted, but at least a statement was made. Then, Koch backed off the closing of the parks because this was a political nightmare for him, of course, and then he left it alone for a little while.

Then, later, Dinkins ultimately closed down Tompkins Square Park to renovate it, and so it was closed for a while. Some people probably remember this. It was rebuilt, and that really changed. By that point, the neighborhood had changed. A lot of families had moved in. The park, from then on, really became more of just a normal park for families and for local residents. Before that time, it had been a real gathering place for punks, for anarchists, for radicals. It was a stew of people.

Alison Stewart: Got a bunch of texts. I'm going to try to get to a bunch of them. "Black folks did not love Koch. No rebirth for them." This said, "I worked as an artist for the New York Daily News from '89 to 1999. It was turbulent but exciting to be part of the famous headlines and breaking news." This text says, "I waited tables at Katz's Deli from '89 to '93 and played four rock and roll gigs at a local bar. You could still smoke in bars and make a living as a musician. It was possible because live music in New York City nightlife was happening."

You talk about so many people in this book. Al Sharpton, you talk about Spike Lee, you talk about all of the cases. You talk about Trump. People are going to have to read your book to find out more. When you think about the city today, when you walk out today, what do you see as the biggest influence that can be traced back to the years of '86 to '90?

Jonathan Mahler: Yes, really, the entire city. The city we are living in was the city that was born in those years. I think that it was still being transformed. We were talking about Tompkins Square, very good example. You could see that the neighborhood was starting to gentrify, and that's what caused this crazy collision of social forces in Tompkins Square and in the surrounding neighborhood. The writing was already on the wall, right? People were already moving into the neighborhood. Old tenements were getting renovated. The whole character of the neighborhood was changing. I think that same process would ultimately spread all across the city.

Alison Stewart: Gentrification?

Jonathan Mahler: Exactly, and into the boroughs. Obviously, I live in Brooklyn. We have seen it all across Brooklyn as well. All of that, almost like dominoes just started. That process started in the '80s with this "rebirth." It just spread across the city and has been spreading across the city ever since then.

Alison Stewart: Spreading unwieldy, as some would say.

Jonathan Mahler: Yes, I think we won't get into the current political moment in New York, but I think what we're seeing in this mayoral race is very much a direct reaction to this, to what started in 1980s New York, and has been going on really ever since then.

Alison Stewart: The book is called The Gods of New York: Egotists, Idealists, Opportunists, and the Birth of the Modern City: 1986-1990. It is by Jonathan Mahler. You should read the book. Thank you so much for coming in.

Jonathan Mahler: My pleasure.