The Final Years of Frederick Douglass (Full Bio)

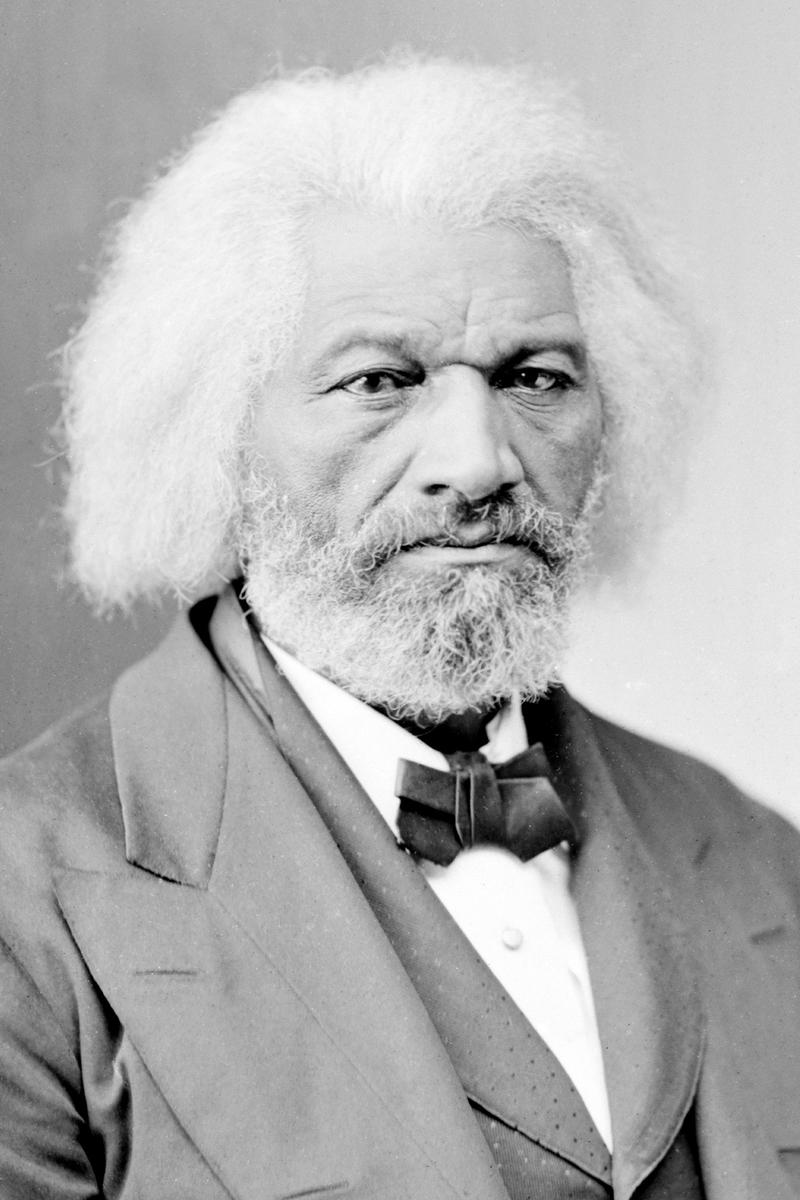

( Brady-Handy Photograph Collection (Library of Congress) / Wikimedia Commons )

[music]

Alison Stewart: You are listening to All Of It. I'm Alison Stewart. For the final installment of our July 4th show on the life of Frederick Douglass, we're going to talk about his later years and how the world reacted to his death in 1895. At this time in his life, professionally, Douglass was a bit adrift. Although he was still on speaking tours, he was no longer publishing his newspaper. In his later life, he was given various appointments. Some went better than others.

In the 1870s, he struggled as the president of the Freedman's Savings Bank, which was created for newly freed slaves to secure assets safely. Things got so bad, he had to prop up the bank with his own money. In the 1880s, he was named as the US Minister to Haiti and spent a lot of time on the island, even during a time of intense political violence, but his version of how the US and Haiti should interact was different than the opinion of President Harrison's administration.

In 1882, Douglass lost his wife of more than 40 years, Anna. He remarried two years later, which prompted a scandal. His new wife was named Helen Pitts, a much younger white woman. When Frederick Douglass died in February of 1895 at the age of 77, people across the country mourned his passing, and thousands came to pay their respects at his funeral in Washington, DC. I asked David Blight why Frederick Douglass started feeling adrift in his later years.

David Blight: Well, he's adrift now because he can no longer be absolutely certain what his profession really is. He doesn't have a newspaper anymore. His reason to be for so many years was getting up with his newspaper. 16 years of The North Star and then Douglass' Monthly, and then two and a half years of the New National Era there in DC in 1870, '71. He now makes a living largely by the lecture circuit until he gets his first federal appointment from Rutherford B. Hayes in 1877 as the marshal of the District of Columbia.

That brought a salary. That's the first time in Douglass's adult life that he had ever been paid something resembling a salary. It was a decent salary. I think it was something like $8,000, which is real money in the 19th century, serious money. He also gets involved in various business ventures. 1874, you mentioned the Freedman's Bank, which was a disaster. The Freedman's Bank had been created right after the war. It was one of the greatest ideas of reconstruction, but it was never fully capitalized.

When Douglass took it over, number one, he was not a banker. Number two, he did not fully understand the condition the bank was in. It was already failing. It had a board that didn't care about it anymore, and the bank, in the summer of 1874, failed on his watch. He will end up doing testimony before Congress on and off for the next eight years or so because of that bank failure.

He did other ventures. There were ventures in real estate, some of which actually did succeed. He ends up buying homes and renting apartments in DC and Baltimore. He got his sons involved in that. He's trying to make a living, but he's making that living primarily with his voice. Douglass would do lecture tours, especially in the winter, of three months at a time, four months at a time, all across what we call the Midwest.

He would lecture from Upstate New York all the way out through Ohio, Michigan, Wisconsin, Iowa, in the dead of winter. He would speak every day or at least every other day. He had a standard fee of $100. He would sometimes ask for more and the expense of the train. He would come back from one of these lecture trips with $3,000 or $4,000, which is in some ways the way his extended family was supported.

He also made money off of his real estate investments and so on, but these were the aging years for Douglass. It is also the time in the 1870s when reconstruction is falling apart, when the great dream of emancipation manifested in the 13th, 14th, and 15th Amendments is being defeated by the white South and then kind of defeated again in the late 1870s and into the 1880s.

Douglass is still trying to organize, as many others were, Black conventions and Black organizations and Black protests up until 1883 when there was this devastating Supreme Court decision, the so-called Civil Rights Cases of 1883, which, in effect, neutered the 14th Amendment or all but abolished the 14th Amendment in terms of enforcement. These were in some ways despairing years. Then Anna, his wife, died in 1882.

I have a chapter in the book called, I think it's The Joys and Sorrows at Cedar Hill. There were many sorrows. There's Anna's death, but of their 21 grandchildren, I forget the number right now, about 13 of them died in their childhood. They were always conducting funerals from Cedar Hill, one after another. Anna dies, but then he remarried in what became-

Alison Stewart: Scandalous.

David Blight: -without a doubt the most scandalous marriage of the 19th century. I don't know what else you would compare it to, especially in terms of its press coverage. Anna dies in '82. He remarried in the winter of 1884, about a year and a half later, to a woman named Helen Pitts, who was about 20 years younger, very well-educated, Mount Holyoke graduate, a woman who came from an abolitionist family in Western New York.

She had classic abolitionist credentials. She'd worked in a contraband camp in DC during the war. She even caught malaria there and had to go home. She almost died. He married her after he had hired her as one of the clerks in the Recorder of Deeds Office in Washington, DC. Now, this needs to be understood, as recorder of deeds, he got eight appointments as clerks. This is to process all the documents about real estate in the District of Columbia.

The first four people he hired were his four adult children, and then he gets hammered in the press in Washington for nepotism. He also hired this young woman named Helen Pitts. Helen Pitts worked at a desk right next to Douglass's daughter, Rosetta. They were almost the same exact age. One day Rosetta was sitting at her desk in the late afternoon, and in walked a reporter and said, "Miss Douglass," or Miss Sprague was her last name then, "Do you realize your father just bought a marriage license down the hall here?" It was in City Hall in the district.

Rosetta must have had a reaction, something like, "What?" But sure enough, Helen and Frederick had been married that afternoon in the parlor of a Black minister named Francis Grimke, a good friend of Douglass's. They had decided to not tell a soul. They didn't tell any of Douglass's children until after the fact. They decided to face the storm of this after instead of before, and there was a storm that went on for months in the press. Here, again, he had a companion now who-- They read books together. They now traveled together. She was a public wife. They appeared together in public.

In 1886 and early '87, they did an 11-month tour of Europe and of the Mediterranean. That is just extraordinary. He kept a diary, happily, on much of that trip. She kept a small diary. By all accounts, this marriage worked. She was exactly the kind of companion he seemed to need, and perhaps he was for her as well. It was her first marriage, her only marriage, but it was a difficult thing for Douglass's family.

Douglass's children never really warmed up to Helen. That's putting it mildly. They just never really took Helen in as their own. She tried her best to take them in, but the press went crazy over this. In fact, my favorite thing about press coverage was that the more and more this went on for months of scandal in the newspapers, they kept making her younger and him older. Douglass was way in his-- He was 66 and she was 46, but, man, by the time the press got finished with this, he was in his 70s, she was in her 30s. He was robbing the cradle.

He took a lot of heat from Black Americans and white Americans, but he also had supporters on both sides of the racial line about this. This is the 1880s. The most famous Black man in the country marries a white woman 20 years younger. That might even be newsworthy today, much less then, but you know what? They both handled it with a kind of, well, whatever you want to call it, grace. As they got attacked, they either just looked the other way, or sometimes he would get up and answer and say, "I will marry exactly who I please."

Then in his old age, he would, occasionally, in letters say, "Okay, now I'm going to retire," whatever that means, but then he gets asked by President Harrison, the second President Harrison, to be the US Minister to Haiti in 1889, a position he found he couldn't turn down. It wasn't a first. He was the third Black American to be the US ambassador to Haiti. It was a remarkable experience for two years, and he got blindsided, in a sense.

He probably should have done a little more homework about the history of Haiti, but he got caught up in Haiti trying to enforce an American policy for the State Department that he increasingly did not believe in, and that is that the United States was trying to annex part of Haiti.

Alison Stewart: What was the reaction to Frederick Douglass's death?

David Blight: Well, when Douglass died, in the press reactions and the community reactions and the number of eulogies and memorials, one finds the degree, the scale of the kind of fame that he had achieved. He was this American story by then of the slave who became not only free but-- and not only the orator but the writer. In fact, above all, I think if Douglass were ever here today to answer the question, what were you most proud of, it would be his writing. He wrote millions of words, 1,200 pages of autobiography, hundreds and hundreds of the short form political editorials, one novella, and thousands of speeches.

By the way, Alison, all of his great speeches exist in a text. He didn't just give extemporaneous sermons off the top of his head. He wrote these speeches out. People could quote from Douglass's autobiographies. They could just quote passages that had become part of a common language for lots of Americans, not all Americans. His death was acknowledged by, commented on by people all across the spectrum. It was acknowledged and noted in southern white supremacist newspapers.

Douglass had become, by then, this kind of iconic American figure, and his passing was, for African Americans in particular, the loss of an era. It was the end of a story. He really was almost the last surviving former slave who'd written a slave narrative, in his case, three of them, and lived to then become a spokesman of his people. Here's the final thing about that. It was the trajectory of his life, I think, that brought such attention.

This is someone who was born out on that Eastern Shore, pre-modernity, before the railroad, before the telegraph, before the rotary press, before all of these things that became so much a part of modernity in the middle of the 19th century, all of which he would use, of course. Where would Douglass have been without the rotary press, the railroad, the telegraph, and so on, or, for that matter, steamships?

He's going to live all the way until the middle of the 1890s, a whole new era of modernity, when they had steamships that could cross the Atlantic in eight days, when they had something called electric light bulbs and they had something called the earliest telephones, and they had something called the phonograph, which could record voices. Although so far as we know, Douglass's voice was never recorded. He lives from a kind of pre-modern America all the way across the 19th century to a modernizing America, but look what he lives through.

Alison Stewart: That was the final installment of my conversation with historian David Blight about his biography, Frederick Douglass: Prophet of Freedom. That is All Of It for July 4th. We'll be back tomorrow with some recommendations for the summer, like how to beat the heat, make refreshing cocktails, and where to get the best ice cream in the city. All Of It is produced by Andrea Duncan-Mao, Kate Hinds, Jordan Lauf, Simon Close, Zach Gottehrer-Cohen, L. Malik Anderson, Aki Camargo, and Luke Green.

Our intern this summer is Marissa Braswell. Megan Ryan is the head of live radio. Our engineers are Juliana Fonda, Shayna Sengstock, and Jason Isaac. Luscious Jackson does our music. If you missed any segments of the live show, catch up by listening to our podcast, available on your podcast platform of choice. If you like what you hear, please leave us a great rating to help others find the show. I'm Alison Stewart. I appreciate you listening. I appreciate you, and I will meet you back here next time.

Copyright © 2024 New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.

New York Public Radio transcripts are created on a rush deadline, often by contractors. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of New York Public Radio’s programming is the audio record.