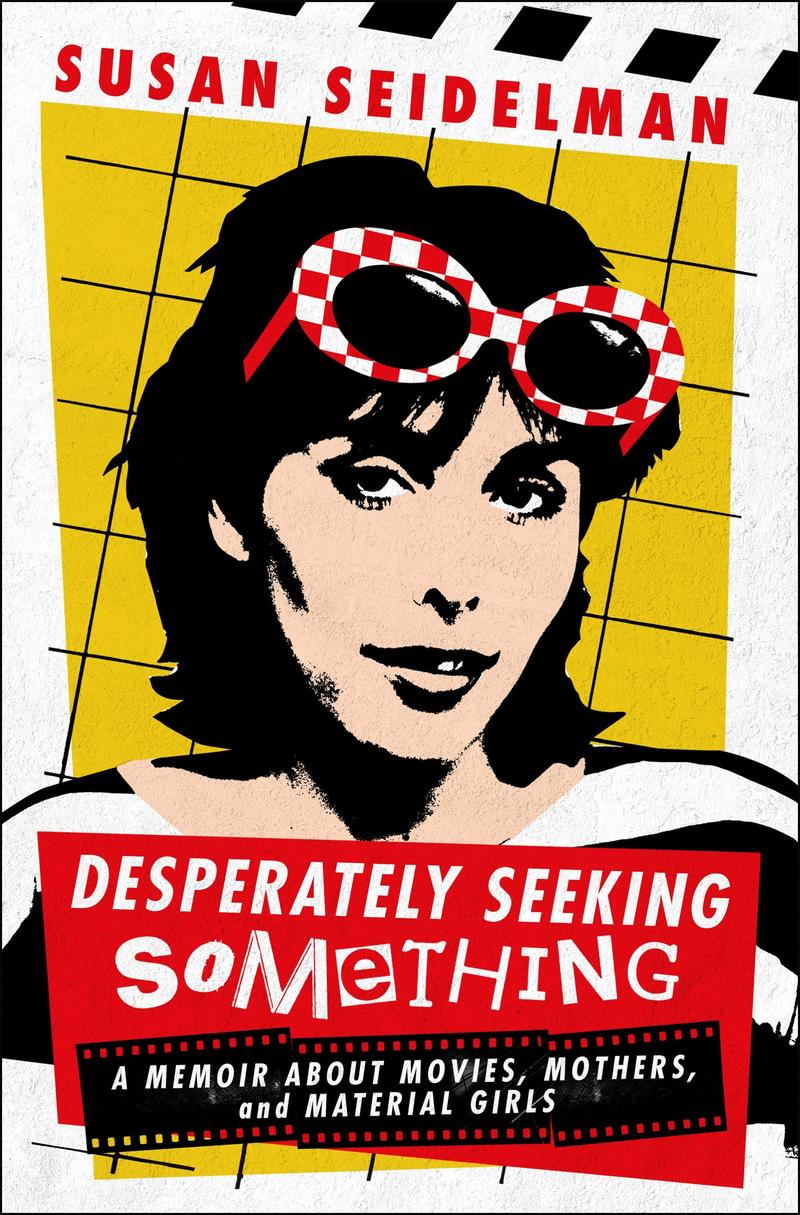

Susan Seidelman's Memoir

( Courtesy of St. Martin’s Publishing Group )

[MUSIC - Luscious Jackson: Citysong]

Alison Stewart: This is All Of It on WNYC. I'm Alison Stewart. Before Greta Gerwig, before Sofia Coppola, before Ava DuVernay and Chloé Zhao, there was Susan Seidelman, a Philly girl who had a mission to tell stories about women, and this was the 1980s. With her 1982 debut, Smithereens being the first US independent film to screen at Cannes and seeing Madonna as a star and desperately seeking Susan to directing the pilot episode of Sex and the City, she followed her instinct.

Her new memoir is titled Desperately Seeking Something: A Memoir About Movies, Mothers, and Material Girls. She writes, "This is not a memoir about extraordinary ambition or enormous drive to success. Yes, I had ambition and drive, but what I had was a vision about the kind of movies I wanted to make and the stamina to make them." This is a story about persistence, about putting one foot in front of the other, heading down a path, and after several wrong turns, eventually ending up where I wanted to go. Susan Seidelman joins me today. Welcome, Susan.

Susan Seidelman: Hi, Alison. Happy to be here.

Alison Stewart: I noticed in your book you said that you didn't want to write a tell-all and you didn't want to name names, and you wait until the end before revealing something major, which maybe we'll get to with a big warning. We'll talk about that later, but how did you decide what went into the book?

Susan Seidelman: Well, it's interesting. One of the things was originally, I just started taking notes. It was during the pandemic, and I didn't really think about writing a book. That time period was so strange, and I was around that same time about to turn 70. That's kind of a moment when you kind of step back a little bit and reflect on your life. For me, it was just writing down reflections, and then I kind of realized I had about 100 pages of these notes and decided to turn it into a memoir. Part of the reason was also because I realized that when I started out as a filmmaker, I really had very few role models.

I knew of so few women, except for some European directors, women who were making movies. I wish I had read a memoir by a woman film director at that time. In fact, the only woman that I knew who had made a commercial movie was Elaine May, who has a book, has a biography coming out now. I kind of decided to then write a book that I thought might be of interest to the next generation of women filmmakers.

Alison Stewart: We meet your family in the book, including your great aunt, Udi and Tuti, which cracked me up. When you think about the people that you grew up around, who did you learn from the most that really helped you in your career as a director?

Susan Seidelman: In a way, my mother, I would say because although she was a typical suburban housewife of that time, she imbued curiosity in her children. Also, we didn't grow up with a fear of failure. I think that that was really important. It enabled me to try out things that I maybe didn't really have the greatest skillset, but I wasn't afraid to try and then fail and then try again. To me, that was really encouraging and important.

Alison Stewart: We're talking with Susan Seidelman. The name of her memoir is Desperately Seeking Something: A Memoir About Movies, Mothers, and Material Girls. I want to talk about the college experience you had because, wow, it was a happenstance that you ended up in filmmaking. In filmmaking 101, you were looking for credits, a certain amount of credits and you write that you could have been in music making or psychology 101. Once you got in filmmaking 101, what caught your attention about that class? What had a hold on you?

Susan Seidelman: I always liked movies. I would go to the local mall cinema and see whatever was playing there. It was a great form of escape because, as I said, I did come from a safe but protected environment. I kind of felt growing up in the suburbs, I was living in this sort of protected bubble. Movies gave me a way, another look at the world. I never bothered to analyze them, and I had no idea even what a director actually did back then. When I found myself in film appreciation 101, which was truly not a mistake, but it just fit my schedule.

I took that class, and I had a great teacher who made me look at films in a new way and opened my eyes to kinds of movies I had never seen before, like some of the wonderful European directors, and made me think about how films are structured, where you put the camera is important. It says something. Also, gave me a glimpse into other kinds of female protagonists because in the '60s, when I was growing up, basically most of the women characters were either in the kitchen or in the bedroom. In European cinema, there was a much wider range of female protagonists.

Alison Stewart: You decided you had a mission. You said, I wanted to be a professional woman film director who told tales about women's lives as seen through a female lens. As you look back on your career, how hard was it to pull off all three?

Susan Seidelman: Weirdly enough, once I started making films, like my first independent film, Smithereens, it wasn't as hard as I would imagine. Getting financing for films is always challenging, but I think that's a challenge for men and women both. All my films have had female protagonists. Those are the kinds of stories I tell since there are so few women making movies even today. Certainly, there are more women working in television, but in terms of feature films, there still aren't a lot of us.

I also figured that as one of very few women making movies, I didn't want to compete with the guys. There were a lot of great male directors who were telling stories about machismo. They were wonderful filmmakers. Scorsese, Coppola, and De Palma, that whole group who were kind of a generation ahead of me or decade ahead of me. I didn't want to compete with them. I wanted to tell stories that I thought I could tell better than some of the male directors I knew. That became my goal.

Quite frankly, Desperately Seeking Susan was a surprise hit. That was obviously about women through a female lens. It became easier to make some of the other ones, although financing was always a tricky issue in terms of getting the studios to finance the kinds of movies I wanted to make. I think that's a problem for all directors who have a specific point of view, not only women.

Alison Stewart: We're talking with Susan Seidelman, the director of Smithereens, Desperately Seeking Susan, She-Devil, Sex and the City, and about a whole lot more. Her new memoir is called Desperately Seeking Something: A Memoir About Movies, Mothers, and Material Girls. Let's dig into Smithereens for your first film in 1982 about a young girl from the suburbs who decides to make it in downtown New York who starred. How did you find your stars?

Susan Seidelman: Well, kind of accidentally. Originally, when I was making that movie, I put an ad in backstage. That was a magazine that aspiring actors would read, and you could kind of get them to work on your films for free because I had no money to pay any actors. I met with a lot. I auditioned a lot of up-and-coming actresses, but they all seemed maybe a little bit actress-y to me, and I wanted somebody who felt genuine, and that she really was this character of Wren, this very, you know, Wren's narcissistic. She's bold.

Anyway, cut to the chase. A friend of mine happened to go to an off-Broadway play. It was in some loft in SoHo back in the day. There were probably more people on stage than in the audience. He saw this girl, a young woman who we thought was really interesting. He told me about her, and he got her phone number, and I met her. As soon as she walked in the door, there was just something so real about her. I knew she was the person I wanted to work with, and her name was Susan. I kind of been superstitious about that name all my life.

I've worked with a lot of amazing, or a lot of people named Susan have been important in my life. When I met her, we clicked, and I knew that she was right. In terms of the other lead actors, there was an actor named Brad Rinn that was sitting in Washington Square Park, reading a book about acting. Someone saw him and asked if he would want to audition for me. It was somebody who's working on my crew, somebody from NYU. He came in, and he really was a midwestern guy who had literally just arrived in New York. That's the kind of character he was playing.

I thought he would be perfect. Richard Hell, again, I knew of him because I was living downtown and had gone to some of the downtown clubs. I had gone to CBGB. I knew who he was. He had been in a band called Television, and then he was in a band called Richard Hell and the Voidoids. He had this amazing attitude. He had a great look. He was hockey. He was probably in some way similar to the character he plays in Smithereens. My goal was to try to get what I thought was interesting about him as a person, to get that on screen. I think, or I hope I did.

Alison Stewart: Smithereens was accepted to Cannes. First US indie film to do so. It came with risks, as you write in the book, that you had to put up a significant amount of money to have it presented. You were lucky that somebody overheard you and stepped in. Would you tell us how you wound up at Cannes?

Susan Seidelman: Yes. Again, back then, this was the early '80s that I was not really career-oriented. I made Smithereens simply because I want-- I had gone to film school. I wanted to make movies, and I wanted to make movies about the world I knew and a kind of feisty female character that I had seen hanging around, but I didn't think in terms of, "Oh, I'll make this movie and I'll get a distributor or I'll get an agent." I knew about film festivals, but the only one, this was before Sundance, so Sundance wasn't really an option at that time.

I had heard about the Cannes Film Festival, and I simply wrote a postcard to this office in Paris that was the office for the festival saying, "I had a film and how do I submit it?" Then I kind of forgot about that. I would say, maybe a couple weeks later, maybe a month later, I got a call from somebody saying, "I'm a representative from the Cannes Film Festival. We're in New York, and we'd like to see your film." The tricky thing was my film was still in the laboratory in DuArt Film lab because I didn't have the money to pay for the answer print and take it out of the lab.

Fortunately, the man who ran DuArt at that time, Irwin Young, was very supportive of young filmmakers. He was supportive of me, Jim Jarmusch, Spike Lee, a lot of the NYU filmmakers. He let me borrow the film to take it over to a screening room, drop it off. "I promised I would return it to the lab afterwards." Anyway, they watched it. About three days later, I got a phone call from a man with a French accent saying, "My name is Thierry Frémaux, I'm the head of the selection committee for the Directors' Fortnight. I'd like to meet you for breakfast to talk about your film."

We met for breakfast, and I was kind of excited that he was interested in screening the film. He said to me that in order to play in Cannes, I needed to blow the film up from 16 millimeter to 35 millimeter. I needed to get it subtitled in French, I needed a publicist, I needed posters, I needed a sales representative, all of those things which would add up to maybe $25,000, $30,000. I didn't realize it was going to be expensive to send your film to a major film festival, and I did not have the money. I didn't even have the money to get the film out of the lab.

Often luck and timing have played an important part in my life, in my career. Fortunately, literally sitting at the table next to us were two British people who turned to me and said, "I'm sorry, we've overheard of your conversation. We happen to be film sales representatives, and if you let us represent your film in Cannes, we will lend you the money, we will front you the money to do all those things." I said, "Wow, sure." They became the sales reps for the film and enabled me to blow up the film to 35 millimeter and show in Cannes.

Alison Stewart: Our guest is Susan Seidelman. We'll have more with her after a quick break. This is All Of It. This is All Of It on WNYC. I'm Alison Stewart. My guest is Susan Seidelman. She's the author of Desperately Seeking Something: A Memoir About Movies, Mothers, and Material Girls. You write that in Desperately Seeking Susan, it's a love story between two women, minus the sex. You have Rosanna Arquette and Madonna. It's interesting, though, you write that interestingly, you had a little more of an issue with Rosanna Arquette than with Madonna. What are the pros and cons of working with an experienced actor?

Susan Seidelman: This was my first studio movie, so I had never worked with professional actors before. When I made Smithereens, we were all relatively inexperienced. It was kind of guerrilla filmmaking, and I didn't quite have the language. I didn't know the language to talk to professional actors. During Smithereens, we were all in the trenches together, and there was no hierarchy or anything. It was a little different working with Rosanna on Desperately Seeking Susan because Rosanna was just coming off the set of working with Martin Scorsese in a movie.

She had won some awards for a TV series, she had done called Executioner's Song, based on the Norman Mailer book. She had done another movie called Baby It's You with John Sayles. I was learning how to kind of talk to her in different way. I think the other thing that happened around that time was, we had hired the producers, Midge Sanford and Sarah Pillsbury had attached Rosanna to the project even before I was involved. I was involved in the casting of Madonna, and I had no idea at the time that I cast her.

She lived down the street from me. I knew of Madonna because I had seen her Borderline video, one of the early videos on MTV back in 1983. I just knew her as just somebody who was hanging around the music world, the downtown music world back then. What happened is, unbeknownst to everyone, her star skyrocketed from the time we started filming to nine weeks later. When we finished the film, she went from being relatively unknown to being a huge star. She suddenly was on the cover of Rolling Stone magazine.

That changed the dynamic of the movie in the sense that suddenly the press was calling this the Madonna movie. That had to have an impact on Rosanna and on my relationship with Rosanna. Again, I mean, Rosanna is incredible in the movie. Finally, 25 years later, when we had the 25th anniversary screening of the movie, I was able to tell her, I was able to watch the movie and tell her how amazing she was in person because we hadn't spoken in many years, and she is amazing. I think that that made for some tension on set between Rosanna and myself.

Alison Stewart: One of my favorite movies, surely one of my favorite movies. You have great successes in your career. You're nominated for an Academy Award for The Dutch Master. You said that "got put in movie jail". What does movie jail look like? Is it passive-aggressive? Is it aggressive-aggressive? How does one get out of movie jail?

Susan Seidelman: I think that movie jail is passive-aggressive. Movie jail is when you don't get the head of the studio to return your call or your agent waits two days to call you back. That's movie jail. Or when you stop getting the scripts, you would like to be able to read. I think one of the things that I was really aware of is that, it's really-- Well, I knew this actually after Smithereens, knowing that there were so many women who had made one independent movie, then made a studio movie that did not succeed at the box office, and then they instantly disappeared. That's movie jail.

I knew that I needed to pick the right collaborators throughout my whole life. I had to, not just try to find the right actors and the right script, but also the right producers and the right creative partners. Some of those, sometimes, that resulted in a movie I was proud of, but that did not do well at the box office. I think it's true today as well. Certainly, back in the '80s, a lot of movies were judged by their opening night box office report. By Friday night, you knew whether your movie was a hit or a flop or was underperforming, I guess that's a polite way of saying flop.

The surprise in Desperately Seeking Susan, we were shocked that the opening night that the film was generating a buzz. We did not expect that. That was doing much better at the box office than the studio expected. The film I did right after that called Making Mr. Right is a film that I really, really enjoyed making. I was with John Malkovich playing a dual role and Anne Magnuson playing the female lead.

It was so much fun to make, but it did nothing do well opening night at the box office, and then it becomes a self-fulfilling prophecy because when your box office isn't doing well, the studio cuts back on the advertising, cuts back on the number of screens, movie theaters, and then the film just kind of disappears. That is an example of movie jail. I was also aware that being a woman, I knew a lot of male directors who made movies that were nothing commercially successful, and they went on to make many more other movies, but that was not the case with female directors.

Alison Stewart: My guest is Susan Seidelman. We're talking about her memoir, Desperately Seeking Something: A Memoir About Movies, Mothers, and Material Girls. You directed the pilot for Sex and the City. How are you pitched Sex and the City?

Susan Seidelman: It's interesting because I'm a movie person. I love movies, and I had no great desire to direct episodic TV. My agent sent me this script written by Darren Star, the executive producer of Sex and the City. I read it and I loved it. I was surprised at how much I liked it because this was 1987, I think, and suddenly, HBO was on a roll. They were kind of changing the way we would look at television. They decided to make much bolder TV series, like The Sopranos, Oz, and Sex and the City were some of their early bold ventures.

I literally read the script, said I liked it, and that I would like to have a phone conversation with Darren Star, the producer and writer. We had a great and relatively short conversation. He said, "I'd love you to do it." I said, "I'd love to do it." One of the reasons was, is because it fit into the world that I wanted to make, tell stories about. It was about female friendship. It had strong female characters. It was bold for its time. It had language that I had never heard on TV that represented the way women I knew spoke in real life but you never heard that on television at that time.

Also, it was about the city that I loved. It was a movie-- It's as much about New York City as it is about the four female characters.

Alison Stewart: This is a warning to our listeners. We're going to talk about an issue that comes up late in the book. You wait until the end of the book to reveal that during the MeToo movement that you had been had in a sexual assault. It wasn't in Hollywood, but it was on a personal trip. Why did you wait until the end of the book?

Susan Seidelman: My intention, once I realized I was writing that all these notes I was taking was going to be a book, I really wanted it to be a book that could also be a kind of guide or be of inspiration to young women directors because I didn't really have a role model. That was my intention. This MeToo chapter didn't totally fit in with that overview. As I was writing the book, this was, as I said, in the middle of the pandemic, the Harvey Weinstein trial was on the news.

I knew many of the actresses who were involved in that, involved with Harvey Weinstein, who had their careers blackballed as a result of that. Women like Mira Sorvino. I think Rosanna was also involved. There were women I knew. I thought, how can I write this? How can I write a memoir where I do talk about my personal life and not include my own experience? Because what my experience had in common with the Harvey Weinstein story is that it's all about the powerful taking advantage of the powerless.

That happens in many ways, in all walks of life. It's often the same issue involved, somebody who has power taking advantage of somebody who is powerless. That's exactly what happened in my situation.

Alison Stewart: Of all the films that you're watching these days, which one just you look at it, you think, "Ah, that person gets it. I really like that film."

Susan Seidelman: Well, I have to say, the person that, whose work I really like is a British woman named Emerald Fennell.

Alison Stewart: Oh, yes, definitely. Yes.

Susan Seidelman: I like her sense of humor. I think she's a great visual stylist. I think she's bold. I think her films have a kind of energy and a fearlessness to them that I respond to. I think that's really interesting. What I find also interesting is that, let's face it, the movie business has changed dramatically since the 1980s when I started out. The studios are not making that many movies. Mostly, what they are doing to me seems to be a lot of sequels and prequels, and big-budget comic book, action hero stuff.

Where the more interesting material seems to be turning up is in streaming, a lot of the new TV series. The good news is that a lot of those series are being directed by women directors. I think that's giving hope to women directors, but also that's what people are talking about these days. It's funny because I've taught at NYU over the years. I finished teaching there right before the pandemic, and I noticed that my students, I like to listen in on their conversation before class started.

When I was a film student, no one talked about TV. TV was just a different category. We would talk about Jean-Luc Godard and European filmmakers. When I started to teach at NYU in around 2000, I don't know, '14, '15, I noticed that the students were talking a lot about and inspired by what they were seeing on TV. I remember them talking about Girls, the TV series Girls, and Lena Dunham who was a big inspiration to them because, at the time, she was in her mid-20s and she was running a TV series, and she had done this great little indie film called Tiny Furniture.

Watching how our culture has changed in terms of storytelling has been interesting me over the years.

Alison Stewart: Susan Seidelman is the author of Desperately Seeking Something: A Memoir About Movies, Mothers, and Material Girls. Susan, it was a real pleasure speaking with you.

Susan Seidelman: Thank you so much. Alison, great talking with you too.

Copyright © 2024 New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.

New York Public Radio transcripts are created on a rush deadline, often by contractors. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of New York Public Radio’s programming is the audio record.