Recipes and Stories on the Origin of American Cuisine

Alison Stewart: This is All Of It. I'm Alison Stewart, live from the WNYC studios in Soho. Thank you for spending part of your day with us. I'm grateful that you're here. On today's show, we'll preview some summer movies with Vulture film critic Alison Willmore. We'll conclude our full bio conversation about the life of abolitionist Charles Sumner. We'll talk with author Bobby Finger about his novel Four Squares, which just came out in paperback. That's the plan. Let's get this started.

[music]

Alison Stewart: We are gearing up for the 4th of July weekend, and a new cookbook offers us a way to think about America. It's called Braided Heritage: Recipes and Stories on the Origin of American Cuisine. It's by acclaimed historian Dr. Jessica B. Harris. You may remember her seminal book, High on the Hog: A Culinary Journey from Africa to America, which inspired the 2021 hit Netflix docuseries of the same name. Now, her new book, Braided Heritage, tells the story of how indigenous European and African traditions came together to create American cuisine.

It also reflects on what it means to be from the United States and the traditions that have been passed down from generation to generation. In her introduction, Harris writes, "It's not a work of history, but rather an attempt to remind us just how magnificently mixed we are on the plate and have been from the very beginning of our national story." Braided Heritage is on shelves now. Joining me now is Jessica Harris. Hi, Jessica. It's so nice to talk to you again.

Jessica B. Harris: Hi, Alison. Lovely to talk to you again. How are you?

Alison Stewart: I'm doing well, thank you. In your recent books, you specifically focused on African American food traditions and their connections to the African Diaspora. Why did you decide to turn your attention to the United States' food, tradition, and culture?

Jessica B. Harris: Actually, it's a funny thing. Someone actually asked me to write this book based on a speech that I had done. I am a child of TV and a child of Saturday morning TV, even though I wasn't a child when I was listening to it in many cases. I started thinking about Schoolhouse Rock. Schoolhouse Rock had a song called Three Is a Magic Number.

Alison Stewart: Yes.

Jessica B. Harris: The more I thought about the United States, the more I thought about three and the power of three in the founding of this country and the whole idea of that tripartite thread that creates our braid, our American braid, as I call it.

Alison Stewart: That is the greatest story I have ever heard. Schoolhouse Rock meets Jessica Harris. It was interesting in the book, though, there's also these interviews. These profiles of people who you wanted to talk to for the book. How did you decide who you wanted to talk to for Braided Heritage?

Jessica B. Harris: It's almost as though they came to me. I would say of the 11 people that I talked to, certainly fully 9 were dear friends, old friends. That was the other thing that came out of that whole idea of the power of three, was like, "Doggone it, I know people from all of the aspects of the braid. Let me talk to them." Then the two that I didn't know as well were actually Native American. One being Sean Sherman, who is out of Minneapolis, who calls himself and is very much the Sioux chef, but he spells it S-I-O-U-X.

First of all, I just love the humor of it all, but also I love the fact that he is doing something extraordinary in his work, his culinary work. He is, as he puts it, decolonizing the food of his people. That is to say, removing everything that came with contact, contact with Europeans, contact with Africans, removing it all. He goes back to no wheat, no sugar, no cane sugar, no pork. It's a very interesting cuisine. I had lunch out there a couple of weeks ago, and it was just astounding. Glorious, glorious, glorious food, but food as it would have not necessarily been cooked, but food with ingredients that would have been here.

Alison Stewart: One of his recipes calls for wild rice and mustard green cakes. How is wild rice different from average rice?

Jessica B. Harris: It's an entirely different thing. It's a grain, but it's really almost like a weed. I can't call it a weed, though, but it grows in the marshlands. We see things that are called wild rice. Literally, from my eating in Minneapolis two weeks ago, I was gobsmacked. It's not at all what we think it is. It's this glorious, nutty-tasting, wonderful, wonderful, wonderful grain that is just a beautiful underpinning for anything.

Alison Stewart: The three that you're talking about is the indigenous people, the European, and the African tradition in the United States.

Jessica B. Harris: Absolutely. The Europeans being specifically the Spaniards who were here, who were here before the British, because they go back to the 16th century. When you see places like St. Augustine in Florida, you get a sense of that. Then, of course, the Southwest, the British. The British are the ones that write the history that we know. Pilgrims, the Virginia colonies, and so on and so forth. The Dutch, whom we always forget, but who had large swaths of the Middle Atlantic states under their domination, and then the French.

Then for African Americans, rather than go with specific points of origin, because that gets a little sticky wicket, as they say. I went with different threads. I talk about migration. I talk to one person who's a dear friend who was, unfortunately, the only person in the book who has died before the book was written. I'm deeply aggrieved about that, and innovation. The person who died was a child of the North. We always think of African Americans in connection with the South, but her family had Northern roots. No connection with the South at all.

Alison Stewart: We're talking to acclaimed culinary historian and author Jessica B. Harris. She's revisiting American's origins through the food. It's titled Braided Heritage: Recipes and Stories on the Origin of the American Cuisine. Let's roll it back to the native people. I'm very excited that you put a spotlight on Julianne Vanderhoop, Wampanoag from the island of Martha's Vineyard. So many Vanderhoops on the Vineyard.

Jessica B. Harris: Yes, yes. Then you must know the vineyard to know the Vanderhoops there. They're everywhere, and in a beautiful way.

Alison Stewart: In a beautiful way. Tell us how the food she makes reflects on her tribe's rich traditions, the Wampanoag.

Jessica B. Harris: She does a lot of-- She does clams, clam fritters, and also clear broth clam chowder. We are used to the dairy-based clam chowder, but dairy as we know it was cows, and cows weren't here when you get back to the decolonizing. Clear broth clam chowder, which is just a lovely, lovely thing. Then she also does an almost tempura-battered sugar maple leaf. That's one of those things where the braiding comes early because, of course, the wheat in the battering of it would have been European.

It's a dish that she prepared once we were doing a-- I don't know, we were doing a dinner together for something, and she was doing addition. She had these glorious sugar maple leaves. Sugar maple leaves are not your normal maple leaves. You can't just go out and pick some in your backyard. Unless you've got a sugar maple tree. They are the leaves of the tree that gets tapped to make maple syrup. They have a sweetness to them. When you add that sweetness to the crunch, it's lovely. Quite lovely.

Alison Stewart: You include a recipe that involves bluefish, which can be found in the waters of Martha's Vineyard if you get up early enough. What is the most common way of cooking bluefish? Then what does the recipe offer that extends what is great about bluefish?

Jessica B. Harris: Bluefish is an oily fish. Many people don't like it because it's oily, and they're not used to the texture of it, if you will. What happens here-- I'm speaking to you from the vineyard. One of the things that happens on the vineyard is that it is often smoked. It's often smoked and often comes as a spread. We're eating it almost-- I can't say a pâté, but it's really just a bluefish spread that goes on crackers that shows up on tables all summer long. What Julie does is take it and cook it fresh, and attenuates the taste of it with a lemony aioli that's made with garlic powder and Dijon mustard, and lemon juice. That cuts a little of the oiliness that some people don't like.

Alison Stewart: Was my dad's favorite. Love the bluefish.

Jessica B. Harris: There you go. There you go. When the blues are running, it's a good thing.

Alison Stewart: Let's bring the Europeans into the braid. The second little wrap of the braid, you highlight Melissa Guerra, a food blogger and photographer, you met while you were both on the advisory board for the Culinary Institute of America's campus in San Antonio. What did you find interesting about her story?

Jessica B. Harris: I found her story absolutely fascinating because Melissa is someone who grew up in what she calls the Wild Horse Desert, which is the borderland. The borderland that is a very permeable, or was a very permeable border. She is a McAllen. Her grandfather was Argyle McAllen, but his first language was Spanish, and their people have been in Texas since the 18th century. Now, what I didn't know. In fact, I didn't even know this when the book was being written, so it's not in the book. A Texan friend of mine who also has an Irish name, said that the Spaniards went to get Irish to help them settle because they were also Catholic.

Alison Stewart: Interesting.

Jessica B. Harris: Yes, I found that fascinating. It makes connections. Where Melissa grew up, it was permeable. They used to go to Mexico. They were in Texas. They would go to Mexico for lunch, go back to Texas. Her husband, who is Mexican, was born in the same hospital that she was. They were back and forth. It's a very different feeling for Mexico and borderlands than what we have today.

Alison Stewart: She has a recipe for stewed salt cod in tomato sauce. What makes this uniquely American?

Jessica B. Harris: The tomatoes, for one, tomatoes being American. The cod, again, the braid. Starting early, the cod, the bacalao, is the dish of the seafarers. Codfish was on most, if not all, of the sailing vessels because it could keep. You would have just stacks of it and people who've gone to open markets and seen it, it gets stacked like cordwood, and you can desalinate it and use it. It could keep. It would survive an ocean voyage, but it became part of the food of the hemisphere. That's why it's so widely used in the Caribbean.

It was also widely used on the Iberian Peninsula. We've got the codfish as the base of the recipe, but then we've got tomatoes and bell peppers, which are New World, and olive oil and onion, which is Old World. We get Old World, New World, Old World, New World. Then the salt cod, stewed salt cod, gets turned into empanadas.

Alison Stewart: It's so interesting to look at the ingredients in a recipe and think about where they came from, and what does that mean that they came from that place?

Jessica B. Harris: Indeed. That's one of my favorite things to do, is to just take a look and just-- It's what lets you know that there is, in fact and indeed, a braid, because we are so mixed to deconstruct the food, or as Sean Sherman says, to decolonize it is very, very difficult. We use wheat. We don't think of it as coming from Europe. We use tomatoes. We don't think of them as being New World. We use corn. We don't think of it as coming up and out of Mexico. We do so many things just almost automatically.

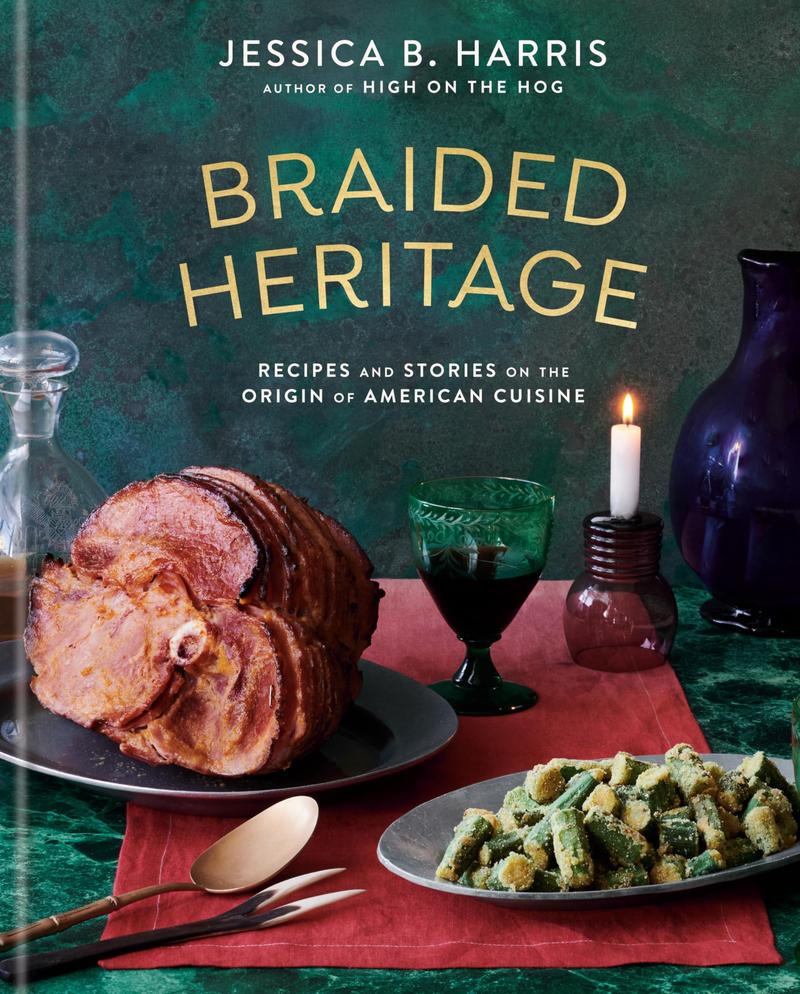

The cover of the book is a ham and fried okra. Ham is pig. Pig is Old World, came with the Spaniards. Okra is African, but it's fried in a cornmeal coating. The corn is Native American, so we've got all three parts of the braid on the cover.

Alison Stewart: It also looks like a beautiful still life.

Jessica B. Harris: Yes, it does. It does. Actually, Kelly Marshall, who was the photographer, just did an extraordinary job.

Alison Stewart: In her latest cookbook, acclaimed culinary historian and author Jessica Harris revisits America's origins through its traditions around food. The book is titled Braided Heritage: Recipes and Stories on the Origin of American Cuisine. Our third part of the braid, African Americans. Tell us which African American recipes you feel don't get enough love when we talk about food culture.

Jessica B. Harris: Oh, I don't know. We get a lot of love for our food. I'm not sure which ones don't get a lot of love. Maybe less well known would be something like watermelon rind pickles.

Alison Stewart: Okay, tell me more about watermelon rind pickles.

Jessica B. Harris: African Americans are noted for there is no such thing as food waste if we can help it. The rind gets pickled, it gets turned into this wonderful sweet and sour pickle. Sweet-ish. With allspice and vinegars, and cinnamon. They have a little sweetness to them. They're wonderful as an accompaniment for all kinds of things. My grandmother, maternal grandmother, would serve them with roasts. I do, and I don't think it's in the book, but I do a appetizer, not appetizer, nibble thing where I wrap a watermelon rind pickle and bacon. You get all of the tastes of the bacon and the watermelon rind. They are just wonderful.

In fact, during the Depression, I can't remember her name, but there was a woman in Harlem who would collect all of the watermelon rinds and pickle them and then sell those. It was a way to make money. The second known cookbook by an African American author, What Mrs. Fisher Knows About Southern Food by Abby Fisher. Abby Fisher was known for her pickles. That whole idea of pickling is something that we don't necessarily think of or connect, but there it is. The title of the book is actually What Mrs. Fisher Knows About Old Southern Cooking.

Alison Stewart: As I'm thinking about it, I'm thinking about enslaved Africans. They had to preserve what they had.

Jessica B. Harris: Exactly.

Alison Stewart: Pickling must have been a huge part of it.

Jessica B. Harris: Pickling could have been a part of it if they were able to get the ingredients, not just of things to pickle, but the vinegars and things like that that they could use for the pickling. It may have come into things a little later, but certainly it was a part of it.

Alison Stewart: You have a recipe for Johnny cakes in the book. First of all, what is a Johnny cake?

Jessica B. Harris: A Johnny cake is like-- It's not really a pancake. It's a bread. It's flatbread, if you will. They are eaten often at breakfast, and they're eaten up and down the hemisphere. Yes, pretty much, I can say the hemisphere, but the northern hemisphere. They are a corn cake. You get some that are called hoecakes, some that are called Johnny cakes. I was so surprised to find them once in the Dominican Republic, where they are called Yanni Kekes. They are just a iron skillet cornbread.

Alison Stewart: There's a recipe here that you say takes you back to my mother's days as a dietitian in African American traditions. The chicken croquettes.

Jessica B. Harris: Yes. Croquettes used to be a way to use food that might otherwise have been not food waste, but not been as used second-day recipes things. African Americans, and generally Americans in the '50s, probably early '60s, and before the '50s, certainly when I grew up, would have croquettes. You might have salmon croquettes for breakfast, you might have chicken croquettes for dinner. It's basically the chopped protein with onion, possibly a little bit of green pepper, bound together with eggs or cream or both, and then fried. It's a patty. Then you can eat them with a mayonnaise or aioli or whatever it is that you'd like to have along with it. Could even have some watermelon rind pickles next to them.

Alison Stewart: I'd love to read this passage from your book and get you to comment on it. You write about America. "The name itself is contentious, taken from an Italian explorer who used to define two continents that were already occupied by whole civilizations. In the United States, we consider ourselves Americans, but Canadians, Mexicans, and Brazilians are also Americans in the original sense." How do you define American culture for the purposes of this book?

Jessica B. Harris: Remember that the book is about the origin of American cuisine. I'm not trying to define or describe contemporary American culture, which has gone so far beyond the braid. Now we'd have to add in all of the people who are Americans. I learned that when I would go to Brazil and say I'm an American, folks would look at me and say, "So are we?" It's like, "Oh, okay, I get it. I totally get it."

Alison Stewart: That's great.

Jessica B. Harris: We claim we claim this continent as ours. Not even this continent, this hemisphere, but we share it with a whole lot of folks. For the foundation of it, for the origin of it, I think got to honor the people who were here. Those would be the indigenous people, the Native Americans. The folks who came and whether it's North, Central, or South, those same cultures pretty much predominate the Spanish, the British, the French, and the Dutch. We've got Suriname and Curaçao and Aruba, Bonaire, Curaçao, and then Sint Eustatius that are Dutch, and the French, Martinique, Guadeloupe, that are still the [unintelligible 00:23:43], that are part of France today.

We've got those cultures still obtain, and of course, the Africans, North, Central, and South. Those three origin cultures, or those three origin points, if you will, of the braid, native, European, and African are what defines this hemisphere. Everybody else comes along, and God knows I understand that. I'm not trying to leave them out of the braid, but they were not necessarily foundational, and I don't want to get into the they came before Columbus or who came across the Pacific and all the rest of that. It's highly possible there were others. That's my story, and I'm sticking to it.

Alison Stewart: Jessica, I'm going to read you this text we just got. "Hi, Alison. I want to say this is one of my favorite segments you've ever done on All Of It. This conversation is so beautiful and well-researched through and through. Whatever opinion one might have on colonization and who does or who doesn't belong where, tracing the origins of these dishes brings me joy to think of the real lives that were being lived on this land over the centuries and the people who were doing their human thing on Earth. Culture mixing is all over the planet. It leads to such beauty and diversity, and story. Thank you for this conversation."

Jessica B. Harris: Thank you to that reader. My goodness.

Alison Stewart: Such a beautiful--

Jessica B. Harris: That listener, I guess, not so much reader that--

Alison Stewart: She will be a reader because she's going to buy your book. The book is called Braided Heritage: Recipes and Stories on the Origin of American Cuisine. It is by Jessica Harris. Jessica, we found Schoolhouse Rock, and this is just for you. This is Three is a Magic Number. Thanks for the conversation.

Jessica B. Harris: Oh, thank you. Thank you so much.

[MUSIC - Schoolhouse Rock: Three is a Magic Number]

Three as a magic number

The past and the present and the future

The faith and hope and charity

The heart and the brain and the body

Give you three as a magic number

It takes three legs to make a tripod or to make a table stand

It takes three wheels to make a vehicle called a tricycle

Every triangle has three corners, every triangle has three sides

No more, no less, you don't have to guess

When it's three, you can see

It's a magic number