Queer Cinema in Hollywood's Censored Golden Age

Alison Stewart: This is All Of It on WNYC. I'm Alison Stewart. Movies today get a rating based on their content and who the Motion Picture Association wants to go. You know the system G for general audiences, then PGR, NC-17. That system has only been in effect since 1968. Prior to what existed was the Hays Code. It was a list of rules heavily influenced by Catholic clergymen that dictated what was allowed and not allowed on screen in Hollywood.

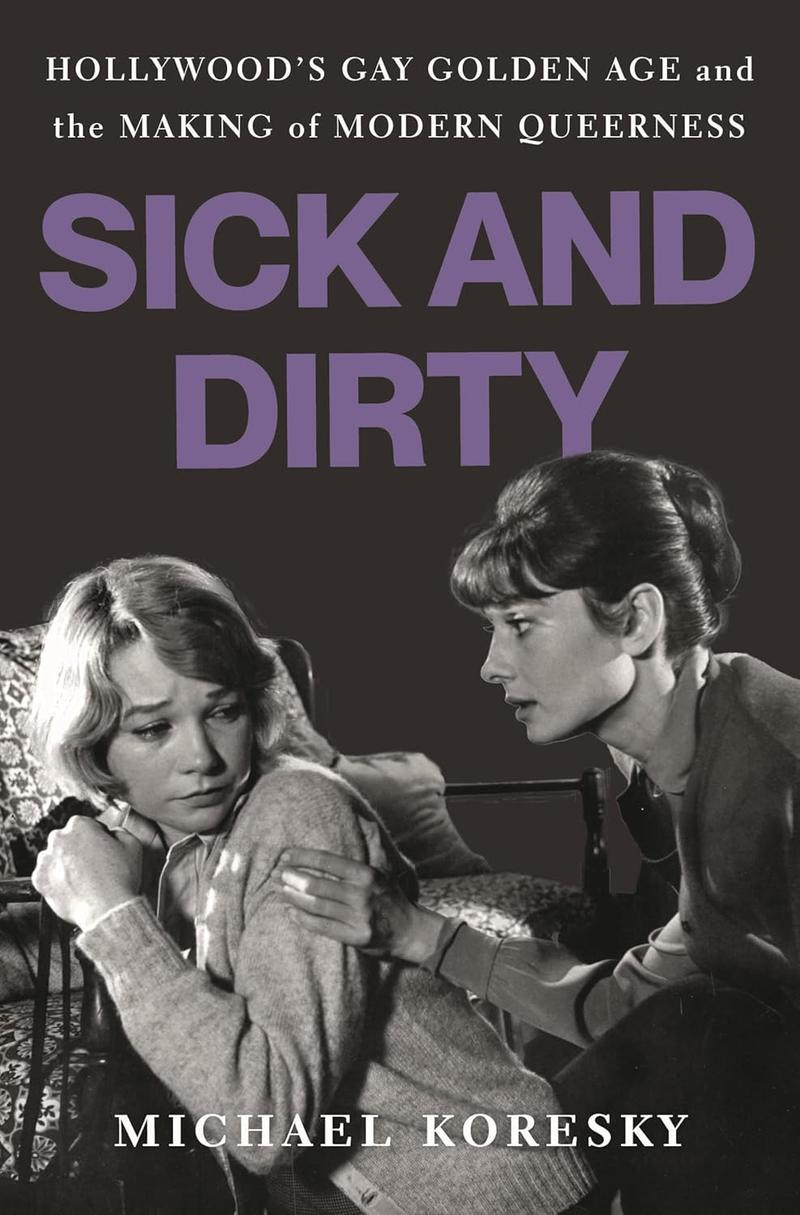

For example, Betty Boop was drawn to be less curvy and started wearing longer dresses after the Hays Code took effect. The rules also included things like no excessive or lustful kissing, no complete nudity, no profanity, and no sex perversion. That last one was a catch-all euphemism used to outlaw depictions of homosexuality. That didn't mean queerness disappeared from Hollywood as Michael Koresky explores in his new book, Sick and Dirty: Hollywood’s Gay Golden Age and the Making of Modern Queerness. Michael Koresky is a senior curator at the Film of Film at the Museum of the Moving Image. Thank you for coming to the studio.

Michael Koresky: Thank you so much for having me.

Alison Stewart: Listeners, what comes to mind when you think of queer cinema from old Hollywood? Are there films from the '30s, '40s, '50s, or '60s that resonated with you? Do you have favorite scene or actor from the past that stayed with you because of what was or wasn't said? Call or text us at 212-433-9692, 212-433-WNYC. Your book begins in the 1930s at the start of the Great Depression. What do we need to understand about Hollywood in those years?

Michael Koresky: Everybody was always hand-wringing over what was going on in Hollywood. I don't think things have changed that much over the years. Ever since the silent era, there's one scandal after another. This was going back to the early 1920s, suicides and rapes, and trials, and one thing after another. There became this sense of Hollywood as a den of iniquity. This idea that there had to be rules written down for Hollywood to follow started to get a lot of currency in the late 1920s.

By the early part of the next decade, there actually was a code written. This was the Hays Code, also known as the Production Code, though it wasn't really enforced all that well in the early '30s. That's why we have this amazing history of Hollywood called the pre-code era. If you watch some of these films, you'll see that they get away with quite a lot. It's because the producers and the studios didn't really have any reason to kowtow to these rules.

Then 1934 came along, and Joseph Breen was hired to head up the new Production Code. An entire new set of rules and dictates were put into effect. From that point on, studios were open to lawsuits, mostly from the Catholic Legion of Decency, who were controlling things from afar. If they didn't get a seal of approval, the films couldn't be released in theaters.

Alison Stewart: I want to go back to that pre-code era. Could you describe what Hollywood was like during that time?

Michael Koresky: The films themselves were a lot of fun. There was a period where you would have not just inferences to homosexuality or what the code called sex perversion, as you said earlier, but you would have clearly queer characters. You would have Roman Bacchanalias. You would have inferences to threesomes. You would have men and women holding hands. You would have nothing terribly explicit, but a lot of sexual, I would say, going past innuendo, a lot of clearly sexual characters and scandalous situations.

This brief period is also one of the reasons why-- This was during the Depression, by the way. They added all of these things to films because they wanted to bring people back to the movies because they had lost two-thirds of their audience after the Great Depression. They were getting all of these properties from Broadway, getting properties from novels, things that were basically considered appropriately controversial. Once the Code really kicked in, that all stopped.

Alison Stewart: Why did the Code kick in? Just because of this general sense of depravity, or was it one person?

Michael Koresky: It was this Joseph Breen. When he was finally hired to head the PCA, it became hardline all the way. He was a real anti-Hollywood and frankly, anti-Semitic presence. When he arrived in Hollywood, when he came from the Midwest, and what he had been doing was mostly PR for the church and for the Pope's visit. The Eucharist Congress was the big event that he had done in the past. He met all of these Hollywood people.

When he was assigned to this perch, he basically took a lot of his biases with him, and he really put in motion what would become the Hollywood that we know from 1934 until about 1968. Though this book ends in 1961, when there was an amendment made to the Code that said sex perversion is possible within bounds.

Alison Stewart: The Hays Code came before Breen, though, right?

Michael Koresky: Yes, it was already written down, but it wasn't enforced until 1934, when Breen was hired.

Alison Stewart: Okay. It was named after William Hays, who was the Postmaster General.

Michael Koresky: He was the Postmaster General under Harding. At least it makes so much sense when you think about it. That the movies would be controlled by the Postmaster General, the former Postmaster General.

Alison Stewart: People didn't necessarily follow the Hays rules. That's why Breen came in?

Michael Koresky: Yes. They didn't follow it because basically they had this system where even though movies would be tagged as forbidden, they would look at films in the script stage or in the production stage and say, "You can't really show this." Then they were able to appeal. When they brought things to an appeals board, they almost always won because the appeals boards were made up of fellow studio heads, producers, and people who said, "Oh, if we had to change this, it would be really expensive for the studio, so why don't you just release it?" That all ended after 1934.

Alison Stewart: Was there any pushback?

Michael Koresky: No one wanted it to happen in Hollywood, but after it was set in place and after the studios realized that they were open to lawsuits and that they were going to get a $25,000 fine per film if they didn't get the seal of approval, they all just laid down for it.

Alison Stewart: Oh, the mighty dollar. People might be wondering, and I was wondering, how does the Catholic Church become involved?

Michael Koresky: The Catholic Church is the whole reason this happened. They had a lot of influence.

Alison Stewart: They had that much influence in Hollywood.

Michael Koresky: One thing that people don't realize, and that I certainly didn't realize until I was researching this book, is that if the Catholic Church says, "We're going to boycott your films," that's 20 million people. That is something that Hollywood could not afford to lose during the Depression. The fact that this was all happening during the Depression is one of the reasons why this happened. Then it stuck for decades.

Alison Stewart: I am speaking with the-- What is it? I have this. I wrote it backwards. I'm sorry. The curator for the Museum of Moving Image, Michael Koresky, his new book is Sick and Dirty: Hollywood’s Gay Golden Age and the Making of Modern Queerness. We are taking your calls. What comes to mind when you think of queer cinema from old Hollywood? Are there films that have favorite scenes from the past that have stayed with you because of what was or wasn't said? Call or text us now at 212-433-9692, 212-433-WNYC.

You start your book with a story about showing students the film, The Children’s Hour. It stars-- it's on the front of your book. Shirley MacLaine and Audrey Hepburn as two teachers who are accused of being lesbians. Why did you want to start with that book, with that film?

Michael Koresky: Frankly, I've been wanting to write about this period of queer cinema in Hollywood for a long time. I've taught about this at NYU in the New School. I have a Criterion Collection, a Criterion Channel series that's all about the history of queer film. I never really found the right way in. Then, when I was teaching this class and I showed them The Children’s Hour, which is a movie that has been dismissed for many decades because it's considered quite dated, because it has this stereotype of the tragic lesbian.

Basically, in the 1961 film, which is based on Lillian Hellman's 1934 play, the Shirley MacLaine character, after they've been accused wrongly of having a lesbian affair by a really nasty child, really one of the--

Alison Stewart: Horrible child.

Michael Koresky: One of the worst kids in movie history, by the way. Total bad seed. After this all happens, Shirley MacLaine's character, Martha, does confess that she has feelings for Audrey Hepburn's character, Karen. After she confesses in this really wrenching scene, she kills herself. I wasn't sure how the students would react. How would 21st century queer or queer interested students react to this. This is a movie that many people have considered difficult or dangerous.

Many were weeping, they were crying, and they came up to me after, and they wanted to talk about it. I couldn't really say very much other than, "We'll talk next week. Let it sit. I'm so sorry. This is a difficult-- Maybe I should have given you a warning first." I realized this was happening a lot during the semester. These movies that had been considered old or dated or whatever people want to say about them, negative images. Negative images. They were really responding to them in a lot of emotional ways, and I wanted to write about that.

Alison Stewart: Let's listen to a little bit of the trailer for The Children’s Hour.

Film Character: This is our lives you're playing with. That's very serious business for us. Can you understand that?

Film Character: I can understand that, and I can understand a great deal more. You've been playing with a lot of children's lives. That's why I had to stop you. I know how serious this is for you, how serious it is for all of us.

Film Character: I don't think you do know.

Film Character: You came here to find out if I made the charge. I made it. I don't want you in this house.

Alison Stewart: That's from the trailer for The Children’s Hour. Let's actually talk to Penny, who wants to talk to us a little bit about this film. Hi, Penny. Thanks for calling All Of It.

Penny: Oh, thanks for taking my call. I guess we crisscrossed because I called and talked to your screener about The Children’s Hour just as you were talking about it. My thing is, Audrey Hepburn was-- I just was text googling. The Breakfast at Tiffany's was 1961, but Roman Holiday was 1953. She was known as this glamor puss. This wonderful actress. I think taking this role was incredibly brave of her. Shirley MacLaine, I was telling your screener, I think, had more chutzpah and brass. She wanted to do daring roles and not be typecast. I couldn't believe this came out in 1960. I probably saw it when I was in grad school in the '80s. Yes. Amazing film.

Alison Stewart: Thanks for calling, Penny. Did you want to respond?

Michael Koresky: Yes, I love hearing that. I think this movie just sticks in people's minds. They don't forget this film. Responding specifically about Audrey Hepburn's participation, this movie was directed by William Wyler, who also directed Roman Holiday, which was the film that, of course, made Audrey Hepburn a huge star and won her the Oscar. By the time William Wyler came to make this movie, which, by the way, was a remake of the original Children's Hour adaptation that he himself made in 1936, which was called These Three, and they had to take out all the gay content.

When they were able to make this in '61 because of an amendment to the code, he went to Audrey Hepburn because they had a relationship. Back in the '30s when this play was on Broadway, they couldn't get anyone to read for this because it was too dangerous. Then casting the movie was easier because they made it into a heterosexual love story. The 1961 version, by the time they wanted to make it a film about this lesbian issue, again, a movie that was about this accusation, it was easier to get braver actors to come on board. Audrey Hepburn did it because she had this relationship with William Wyler.

Alison Stewart: We're talking about the book Sick and Dirty: Hollywood’s Gay Golden Age and the Making of Modern Queerness. We'll have more of your calls and want more with Michael Koresky after a quick break. This is All Of It.

[music]

Alison Stewart: You are listening to All Of It on WNYC. I'm Alison Stewart. With me in studio is Michael Koresky, senior curator of film at the Museum of the Moving Image, and he's the author of the book Sick and Dirty: Hollywood’s Gay Golden Age and the Making of Modern Queerness. You write about Dorothy Asner, or Arzner, excuse me.

Michael Koresky: Arzner.

Alison Stewart: In the book. She was a director, one of the few directors of the time. What was radical about the way Arzner presented herself?

Michael Koresky: She was extremely sure of herself and her identity. We know now for her to be lesbian, they didn't come out of the closet, but everybody knew. She always wore tailored suits and hats, and she looked about as dapper as any male movie star of the day. The amazing thing is that she also had all these publicity shots done with starlets. It was very clear she was dressed in men's clothes. The women were dressed in starlets' clothes. Sometimes the women would be draped across her, sometimes they'd be sitting on her lap.

She was herself. She was the only female director working in Hollywood in the '30s and early '40s. She was the only one. She was such a pro that everybody wanted to work with her. She tried to leave Paramount, and the studio had to blackmail her into staying because she was so amazing.

Alison Stewart: How did queer themes show up in her films?

Michael Koresky: This is one of the more interesting things in the book is that during this period of time that I'm writing about, queer themes do have to be sussed out, because you couldn't actually express anything. It all had to be under the surface. It all had to come out with desire and the things that aren't said and the things that are phantom-like. For Arzner's films, I think it comes out in these films that are very much about homosocial female relationships. She's not interested in the traditional heterosexual couplings, basically. If there's ever a man in these movies, he's really pathetic, and you're not interested in him.

The film that I write about at length is called Dance, Girl, Dance. It's Lucille Ball and Maureen O'Hara, two amazing redheads. Unfortunately, the film's in black and white, but you can see the red hair if you look really closely. It's all about their professional friendship and rivalry. There is this love interest, but he's so pathetic and so pushed off to the side that it's so clearly about the women. There's also an amazing feminist angle.

It has a scene that is about as feminist as any film from that era where she looks back-- She's a performer, the Maureen O'Hara character, and she looks back at an audience of men and she basically turns the camera back on them and tells them that they're pathetic to objectify her, and that they should go home to their wives. It's very, very striking.

Alison Stewart: Was she affected, Arzner, affected by the Hays Code? Was her career affected?

Michael Koresky: Her films were-- Let me put it this way, the Hays Code affected everybody. She didn't necessarily try to get gay themes into her movies because that wasn't where she was on the surface. Say for Dance, Girl, Dance, the women are burlesque performers. There's a scene where Lucille Ball, it's a very pivotal scene in the film. She's supposed to be doing a striptease. When Joseph Breen got word that there was a striptease, he absolutely freaked out.

There was even an article about Lucille Ball going downtown Los Angeles to learn how to do a burlesque dance. She said, "I have to learn how to do it for the Hays Code." It was in the newspaper. Then, at the end, they put her behind a cardboard tree while her clothes fly out.

Alison Stewart: Of course. This text says, "I remember watching The Children's Hour as a 10-year-old in the '60s and knowing there was a message and lifestyle imply, but not quite sure or aware of what it was." This is Raymond, who is calling us from Turtle Bay online, too. Hi, Raymond, thanks for calling All Of It.

Raymond: Hi, thank you so much for having me.

Alison Stewart: Sure. What's your question?

Raymond: I want to ask about The Birdcage. The Birdcage is made at a time where Robin Williams could play that character. I'm wondering if, do you think that movie could get made today with Robin Williams playing that role? Just in terms of how Hollywood casts now. I just want to hear your thoughts on that.

Michael Koresky: That's an interesting question. Of course, Nathan Lane, who's the other half of that couple, is gay in real life. Here's a little plug. We're going to be showing The Birdcage at the Museum of the Moving Image next weekend, twice for Father's Day weekend.

Alison Stewart: Perfect.

Michael Koresky: I'm very excited. Nathan Lane's actually coming to the museum--

Alison Stewart: Oh, that's great.

Michael Koresky: -- on Sunday the 15th. On the 14th, the author of the amazing new book about Elaine May, Carrie Courogen, is going to be coming. I know she's been in this show.

Michael Koresky: That's a little plug, because I love The Birdcage. You know what? I think that was a little controversy that had been drummed up over the past few years about straight actors playing gay. I feel like it's actually the pendulum swung back a bit. There are movies coming out this year that just played at [unintelligible 00:17:16] that are about gay couples played by straight actors. I, of course, would love it if gay actors got roles and they were cast and they were able to play open, loving, desirous gay men. I want that to happen all the time. I also wouldn't want actors like Robin Williams to not get terrific roles. I'm torn. I think it goes either way.

Alison Stewart: We talked to the actress who plays Betty Boop, and Betty Boop had a big redesign under the Hays Code. Longer sleeves, not quite as much cleave have shown up. How did the Hays Code dictate the depiction of women's bodies and women's sexuality?

Michael Koresky: Joseph Breen was terrified of women and terrified of women's bodies, clearly. One of the first things he did when he got the job in 1934 was look at films that had already been produced. Later, he would strike things at the script stage. There was a film called The Merry Widow by Ernst Lubitsch with Jeanette MacDonald, and he noticed that her shoulders were being a little too bared, so they had to cut that.

We're talking about really, really ridiculous, draconian stuff. From that point forward, anything that related to bodies was verboten. He didn't want people to remember that we had bodily functions. He didn't want to show toilets. He didn't want to show people urinating from behind. There was a lot of stuff. If you're reminded of people's bodies and genitalia, somehow that's vulgar.

Alison Stewart: My guest is senior curator for film at the Museum of the Moving Image, Michael Koresky. His new book is called Sick and Dirty. Our phone number is 212-433-9692, 212-433-WNYC. What comes to mind when you think of queer cinema from old Hollywood? Give us a call, 212-433-9692. Another film you write about in the book is Tea and Sympathy. It's based on a play by Robert Anderson. It's about a boy who doesn't quite fit in at prep school. Let's listen to a little clip of the trailer.

Movie Trailer: Tea and Sympathy captures every stinging and dramatic moment of Robert Anderson's powerful play. It brings together the sensitive schoolboy and the housemaster's wife, who knows he is more of a man than any of those who call him sister boy.

Alison Stewart: How do the play and the film differ?

Michael Koresky: You heard right there the term sister boy. It differs from the play because in the play they use the word sissy. You couldn't use the word sissy in films because it was one of Joseph Breen's most hated words. You couldn't say pansy, you couldn't show pansies, but you also couldn't say a pansy sissy. They changed it to sister boy.

Alison Stewart: Sister boy.

Michael Koresky: Which is a very strange word. It's become code for the most ridiculous excises or changes for Hollywood cinema. The whole film was unchangeable. That's the thing. They bought the rights to this play because it was a hit on Broadway. It had Deborah Carr on Broadway, and she would reprise that role in film. After they bought the rights, they had this two-year back-and-forth, the studio and the Breen office, basically saying, "You can't really make this movie." They said, "But we are going to make this movie." "Okay, well, then you have to change everything about it.

That didn't really work for Tea and Sympathy. Once you actually dig into it, there's no way of excising the queerness from the center of the story. That's what it's about. It's a movie about masculinity. It's a movie about how American society's look at how men are supposed to be is toxic and dangerous, and vile. That's actually a pretty amazing thing for 1956. I would say that there hasn't been a film-- there hadn't been a film decades hence that was really about that.

Even though that film has been also discounted for decades for being a little too polite, not going so far into the gayness, because they couldn't. I actually think it's a really strong, multi-layered film. Again, my students really responded to it.

Alison Stewart: What happened in 1968? Why did it all change?

Michael Koresky: In 1968, the Code had just been worn away to a nub, and everyone knew that the time was up. I mean, movies like Who's Afraid of Virginia Woolf? Which broke the mold in terms of the words they were allowed to say, the vulgarity. Movies like Sidney Lumet's The Pawnbroker, which actually showed nudity. Things were just wearing away bit by bit. It became fish wrap at a certain point.

Jack Valenti was hired to head up the MPAA, and there was an entire new rating system put in, and the code was effectively dead. I do think things like the amendment made in 1961, which allowed to be made, were the actual milestones that got to that point. People talk about '68 as the very end. I think '61 is the beginning of the end. That's where my narrative ends.

Alison Stewart: Let's try to get Larry from Park Slope. Larry, can you give us your comment in a minute?

Larry: Yes. I'm doing research now on a film called Advise and Consent, Otto Preminger, which depicted a great breakthrough in terms of the depiction of homosexuality in a Black male scene of a senator in a very sympathetic manner. I think it's an extraordinary film as [unintelligible 00:22:20] and breaking the Code.

Alison Stewart: Thank you so much for calling in, Larry. Did you want to respond?

Michael Koresky: Yes. What's interesting is that Advise and Consent and The Children’s Hour were two of the films that were cited to make the amendment of the Code. Like the same producer sent a letter, Arthur Crimm, he sent a letter saying, "These two films are going to be made by my studio, and we need to change the Code so we can make these films. Children's Hour and Advise and Consent-- This third movie was called The Best Man, which is adapted from a Gore Vidal play. Those three films were the films that started the real change.

Alison Stewart: Got a text here that says, "Gus Van Sant's My Own Private Idaho, such a beautiful representation of the fluidity of male queer identity and sexuality, allows a space for those who identify as masculine to find an image of frailty and softness." That is so beautiful.

Michael Koresky: I love that film.

Alison Stewart: Tell me why.

Michael Koresky: My Own Private Idaho. If we're talking about an era that stands in stark and beautiful contrast to the coded, censorious era, it's the 1990s with the new queer cinema, when all these amazing expressions from these independent filmmakers in American cinema were coming out. My Own Private Idaho by Gus Van Sant is just one of the cornerstone films. It is such a beautiful, sensitive film about men and love, and connection. It's brave. It was just brave.

Alison Stewart: You should read the book Sick and Dirty: Hollywood’s Gay Golden Age and the Making of Modern Queerness. It is by Michael Koresky. Thank you for coming to the studio.

Michael Koresky: Thank you so much for having me.