Poet Robin Walter Celebrates Poetry Month

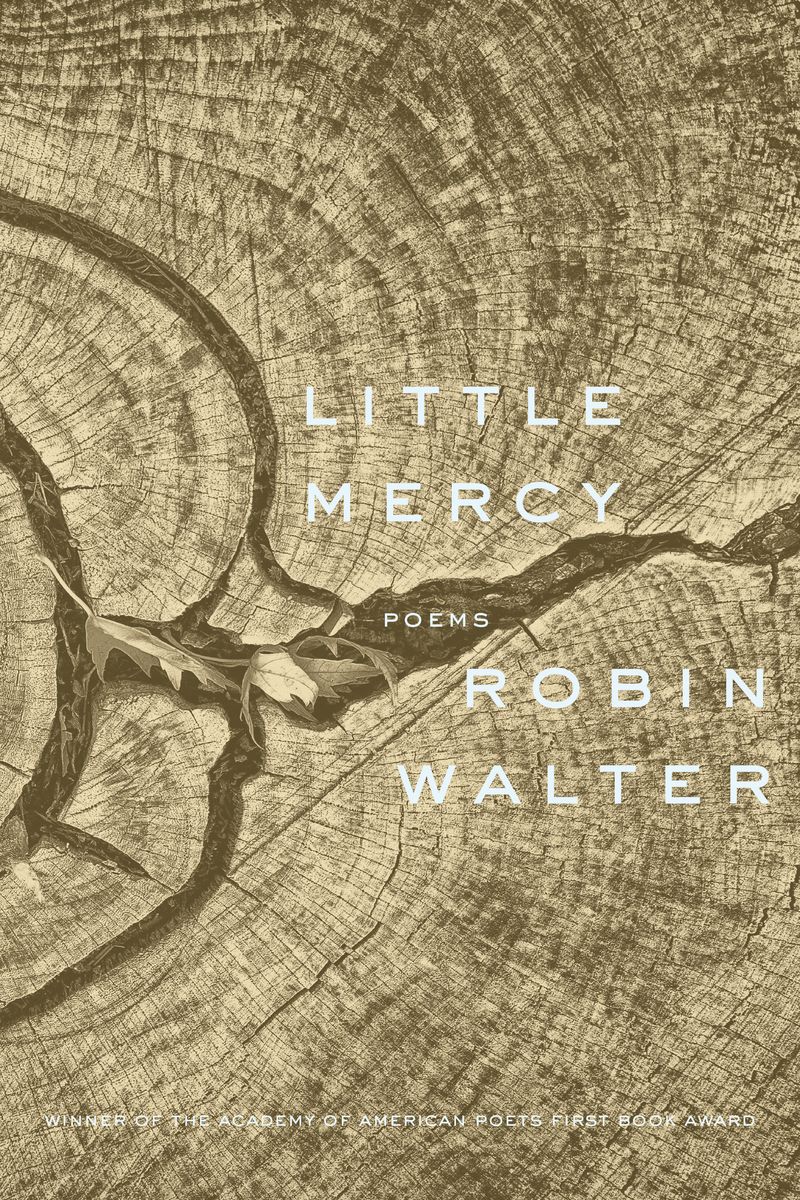

Alison Stewart: This is All Of It on WNYC. I'm Alison Stewart. The 2024 winner of the Academy of American Poets First Book Award is Robin Walter, my next guest. Started in 1975, the award provides financial support and exposure to a poet. Robin Walter's book is called Little Mercy. The legendary poet, Victoria Chang, helped select Walter's work, saying, "The beautiful and meditative poems in Little Mercy are painterly, showcasing a perceptive speaker with a keen eye. These poems quietly and gently ask us to look at all the natural beauty and cruelty, but mostly beauty we face each day, every minute, every second of our strange time on this earth."

Robin Walter is an associate professor at Colorado State College. Tonight, she'll be appearing at Books Are Magic on Montague Street at 7:00 PM. She joins us in studio to help celebrate National Poetry Month. Welcome, Robin.

Robin Walter: Hi. Thank you so much for having me. It's an honor and a delight.

Alison Stewart: Listeners, do you write poetry? Why? What made you start? Our number for calling and texting is 212-433-9692, 212-433-WNYC. If you'd like to share a little bit of your poetry, go for it, but we ask that you keep it shortish, maybe a minute, so that we can get as many of you on the air as possible. Our number is 212-433-9692, 212-433-WNYC, or you can send it to us via social media @allofitwnyc. What was it like when you found out that you'd been selected for the first book award?

Robin Walter: It was pretty stunning. [laughter] I was caught speechless. I was walking out of class and got this call from Ricky Maldonado and he relayed the news and I began weeping immediately in the quad around and students coming and going. I truly was just floored and humbled and delighted.

Alison Stewart: What did it mean to you emotionally? Then, practically, what did it mean to you?

Robin Walter: Emotionally, it meant everything to me. I think Little Mercy was a book I've labored and labored on and had been sitting with it for several years before it got picked up for publication. It was just this incredible booing, bolstering moment of belief both in the work and also in myself as a poet. Practically, it's newly in the world. It came out in April 1st, so I'm just beginning to come to understand what it means practically. Right now, I'm just delighting in the opportunity to share it with folks.

Alison Stewart: Did I read that you get to go to Italy?

Robin Walter: I do. [chuckles] I get to go to Italy this summer as part of the Civitella Ranieri Foundation residency, which is a true wonder. I'll be there for six weeks this summer, and we'll be at work on the next project.

Alison Stewart: What does the title "Little Mercy" mean?

Robin Walter: Hmm. In some ways, it is both a token of mercy being scant, and also mercy appearing in little places and littlenesses in the ways in which we find shelter in these small moments or small beings and birds and a blade of grass, these small entities around us, and how it is that we can find solace and shelter in those.

Alison Stewart: Let's hear something from Little Mercy. We're going to hear a poem called Beyond the Meadow.

Robin Walter: Beyond the Meadow

A thread of moonlight there, tangled in wet pine

Rustle of wings in dark canopy

Shadow of wingtip etched into palm

Each soul that has nearly slipped the noun of the body remembers rivers cold mercy

Every palm touched by shadow carries it

Alison Stewart: That's Robin Walter reading from her book of poetry, Little Mercy. I read that partially, this book was because you suffered a bit of an accident involving a mule.

Robin Walter: That's right. [laughter]

Alison Stewart: There's so many things to unpack there. First of all, what happened?

Robin Walter: [laughs] I was leading outfitting trips in the Bighorn Mountains in Wyoming. I was going to try to catch a mule for a trip that I was taking out later that day. She was being difficult to catch, so I had a halter in my hand, and I had a bucket of grain, and I had my dog with me, Banjo. Banjo got a little protective of the grain and went to nip at the mule's nose when I was trying to catch her, and the mule reared up and clocked me in the face.

Alison Stewart: Oh, no.

Robin Walter: That resulted in several years of surgeries and-

Alison Stewart: Oh my gosh.

Robin Walter: -just a real long recovery period, which the little mercy of that accident was that I was able to really have some time to just sit and take in the world around me in a way that I likely wouldn't have if I was moving in the fast ways that I ordinarily do, that we ordinarily do in the world. I was grounded with very limited mobility for the summer and wrote the majority of this book during that period of recovery.

Alison Stewart: Oh my gosh. Where did you recover?

Robin Walter: I was situated in a little cabin up in the foothills of the Bighorns in Wyoming. It was just really on that tiny porch with this symphonic landscape around me. As I wasn't able to venture out into the world much, I truly was just sitting and noticing.

Alison Stewart: How did being alone contribute to the writing of this project?

Robin Walter: Probably had a lot to do with the project, though the truth is, I didn't feel very alone while writing it because there were so many-- I think part of the book is interested in finding company and companionship in the world around us. That was certainly what transpired that summer, was I found so much kinship in this little nest of wrens that had made a nest in the eaves of the porch. There was just a daily practice of checking on them, writing a poem, reading a book, and the work followed in that way.

Alison Stewart: This may be a little bit of a practical thing, but once you finish with the poems, how did you organize them in the book?

Robin Walter: I thought a lot about the architecture of a nest, actually, while assembling these poems. There was, of course, the seasonal that helped structure the poems, but also there was just the synchronicity of how a bird builds a nest. A twig going here, a blade of grass going here. I thought so much about the material nature of language in a similar way of the line being assembled as a twig as part of a nest. In a lot of ways, the nest could have been made in any kind of way. The poems could be arranged in any kind of way, but fell into this particular structure that felt right.

Alison Stewart: The veteran poet Victoria Chang said that you asked us to look at nature. What should we be looking for?

Robin Walter: It's a beautiful question. I think the key is to not answer that question and to be open to what it is that appears when we are able to become wakeful to the world around us, when we are able to be present to what reveals itself. I think so much of the book is a practice in attention. I'm reminded that the word attention is tied to, in ancient Greek, the verb shepherd. To care for, to promise, to give into safekeeping. I especially love this idea of promise as it relates to poetry.

Alison Stewart: My guest is Robin Walter. Her book is Little Mercy. She's the winner of the Academy of American Poets First Book Award. You're going to read another poem for us. It's called What Grammar For Prayer. [silence] You got it. There you go.

Robin Walter: Somewhere in here. My apologies. [silence]

Alison Stewart: You've got all your post-its? [laughs]

Robin Walter: I can't find my post-its, but they're not serving me at this moment.

Alison Stewart: Is it the one you want? Do you want it? I've got a-- Perfect. There you go. Take that.

Robin Walter: What Grammar For Prayer

Try the shiny black beat, the heartbeat, a little soldier

Try switchgrass, miller moth, moon

Try the moon is not a fist

Try a fist of wet lilacs

Try a fist of wet lilacs shaking

Try nest, stitch, twig

Try the whole thing backward

Twig, stitch, nest

Try nest on its own, nest

Try nothing, not naming at all

Alison Stewart: That's Robin Walter. We had a question for you. The questions me texted it to us. It says, what are your waypoints during this book tour? Do you have any daily practices that support you?

Robin Walter: That is such a lovely question. I actually was just talking to a dear friend, Alejandro Juredias, whose debut book is out recently. He gave me a really good tip, which was mostly just to stay hydrated. [laughter] That's my one waypoint so far. This is my first stop on the book tour. I'm trying to follow his advice. [laughter]

Alison Stewart: When did you first discover you had a relationship with poetry?

Robin Walter: The first time I really fell in love with poetry was I had the wonderful opportunity to visit Alastair Reid, who was a poet based in New York, actually. This was in my undergrad years. I had just taken an intro to poetry class and had just stumbled into this beautiful world and had the great good luck to spend a stolen few hours with him in his apartment in New York. He was at the end of his career and was talking about-- he was sharing these stories of translating Neruda and Gabriel Garcia Marquez and Jorge Luis Borges. He loaded me up with three trash bags full of poetry.

Alison Stewart: Oh, wow.

Robin Walter: I think he was at a moment in his life where he was ready to find poems for these books. I remember just feeling in that moment that poetry really wasn't something that existed on the page, but was much more operal you could enter into. I was so eager to enter into it. I remember writing a mentor of mine about that beautiful visit. He wrote back something that I carry with me from desk-to-desk and home-to-home that I'd love to share that I think speaks to one of the capacities of poetry.

He writes, and this is Jim Moore, "Poetry itself is a kind of translation, translating from the calligraphy of heart into words that allow private experience to manifest. Whether you're translating or not, writing poetry or not, we speak an original language that only one person speaks, only our own selves, and the work of our lifetime is to translate that into a language others can understand. That desire to translate ourselves, to make the text of our lives, our fears, rages, griefs, dreams, passions, uncertainties available to others, is such an incredible privilege and an incredible task as well." Something about that task and that privilege is unending in a lot of ways. It continues to call to me all these years later.

Alison Stewart: Robin, you teach at Colorado State College. What do you teach?

Robin Walter: I teach at Colorado State University.

Alison Stewart: University. Excuse me.

Robin Walter: I teach in the Green & Gold Initiative, which is an interdisciplinary disciplinary program that is interested in building a bridge between STEM and humanities. I'm currently teaching a course in poetry, politics, and place, and I'm also co-teaching a course in poetry and printmaking.

Alison Stewart: What do kids have on their minds as they're writing?

Robin Walter: I asked my students recently if they have hope in this particular moment, and the class of 23 students, not one of them raised their hands. I think that so many students right now are interested in how to find hope, and if not hope, then how to imagine themselves being able to hope. I think so many are just reaching toward that question.

Alison Stewart: My guest is Robin Walter. We're talking about her book, Little Mercy. I'd love for you to read the poem, Robin Has Always Been My Name. When did you write this?

Robin Walter: I wrote this poem the same summer that I was on the porch recovering and was just thinking about how it is we understand ourselves in the world and how we think of our identities and what happens when we lose sight of ourselves and what we might reach toward in order to remain connected to the world and to ourselves.

Robin Has Always Been My Name

It's true, I feel a kinship with birds

As if my mother knew, I'd suspect the body begins at wingtip

Maybe it has less to do with the name than how earnestly I wish my mouth around the little trill, the quavering s held briefly and waterly in the teeth

Sometimes I cannot recall my own name

I mean, sometimes can't sleep, can't speak

Forget all about runs, still the day opens

Call me meadow

Call me horse

River, call me

Alison Stewart: That's Robin Walter's reading. What is a misconception about poetry that you'd like to correct?

Robin Walter: Hmm, that's a lovely question. Oh, one of the misconceptions that I think would be helpful to correct is that a poem has to rhyme. [laughter] I think so many students are taught poetry in a really particular kind of way, in a bygone way. There's so much vibrant, amazing contemporary poetry that doesn't rhyme at all and is imagining and reimagining language in exquisite and inspiring ways. Of course, it can rhyme, but it doesn't have to.

Alison Stewart: You suggested a poem that really spoke to you, Sophie Cabot Black. I'd love to have you read it. Tell us why you chose this poem.

Robin Walter: I chose this poem which is titled "Ice" because it takes the word ice and reclaims what it is that the word ice means in our current moment. I'm so moved by the language.

Ice

A small animal went out to the middle and disappeared

No sign of anything further

At the border where trees no longer take root, the brave track steadfast, written only so far

We grow quiet enough to hear the moan of ice, the rumble of deep water going beyond its beyond

We cannot break open without loss

An ice with nothing more to remember, shifting under its own weight as if it could stay forever

Do not let the word for this stand for something else

It is this

Alison Stewart: Tell us a little bit, do you know anything about Sophie Cabot Black?

Robin Walter: I know that she is a poet based in New York and born in New York. She is interested in investigating our current American moment and combining the pastoral with other current contemporary questions. The reason I wanted to think together about that poem is I think it does what another-- It calls to mind the artist Ronald Rael. He had an installation that I have been thinking so much about.

In July of 2019, he had an installation of a teeter-totter across the US border. What was so compelling about that installation is that if only for the moment of the installation, it reimagined what a border is, what it might mean as a place of encounter and connection and play, without denying the political reality of that site. I think the poem Ice is a similar thing in that if only for the moment of the poem, it recaptures multiplicity and recaptures possibility in the word ice, that it has a bit of a rupture in the stronghold that a current moment has on ice.

Alison Stewart: We've got a couple of calls. Let's go to Maria from New Jersey. Hi, Maria. Let's hear your haiku.

Maria: Hi. This is a haiku, but I'd like to note that the Asians call it haku. This is entitled Youth Mouthing a Tunnel of Ringing Memories, A Young Boy Whistles.

Alison Stewart: Thank you so much, Maria. Let's talk to Linda in New York City. Hi, Linda. Let's hear your poem.

Linda: Oh, great. Oh, okay.

Time's great secret finds its way with the birds from night to day

Once again, the beauty spray of blossom life renews its way

How they cherish each slight sound

Free from details, man has found free to soar on wing not word cheering each other on in sound

Their whole being in this world makes me wonder why can't we find the essence, the center, the key, the secret of their simplicity

Alison Stewart: Thank you so much for calling in. This poem was texted to us. I heard your voice last night from the other room. I wanted to hold your frail, elegant hand once again and see your crazy smile. [laughter] That's a fantastic poem. For someone who wants to write poetry, what advice would you give them?

Robin Walter: I would recommend finding a poem that makes you feel something. Any poem. It doesn't have to be any kind of feeling, just some feeling that it incites and borrow a line or a title from that poem and write towards that feeling. It might be a feeling of anger or ecstasy or longing or desire or anything. You can write toward a way alongside the poem, the original poem, and make it your own.

Alison Stewart: I'm going to have you finish out with your poem, And If, Robin.

Robin Walter: And if the rafter belongs, if only briefly, to nest in the hand to the beautiful wrist

And if the comment anchors and the noun lifts

If language keeps us and couples us

See the little wren lift from thin river of moonlight held in palm

Alison Stewart: Robin Walter was the winner of the Academy of American Poets First Book Award. The name of the book is Little Mercy. She will be at Books Are Magic on Montague tonight at 7:00 PM. Robin, thank you for coming into the studio.

Robin Walter: Thank you so much for having me. Happy National Poetry Month.