Poet Patricia Smith Wins the National Book Award

David Furst: This is All Of It. I'm David Furst in for Alison Stewart, who is staycationing. Coming up on the show this week, we'll be hearing a lot of festive music. On Wednesday, Kate Kortum will be here, fresh off her recent win at the annual Sarah Vaughan International Jazz Vocal Competition. She will perform live for us and preview her upcoming performances at Lincoln Center. On Thursday, klezmer clarinetist Michael Winograd will be in WNYC's Studio 5 to play with his band ahead of his concert at the Center for New Jewish Culture.

On Friday, we continue an All Of It tradition and welcome members of the West Village Chorale to the studio to sing some classic carols live. Later this hour, members of Old Crow Medicine Show are going to join us for a listening party for their new holiday album. Let's get this hour started with some poetry.

[music]

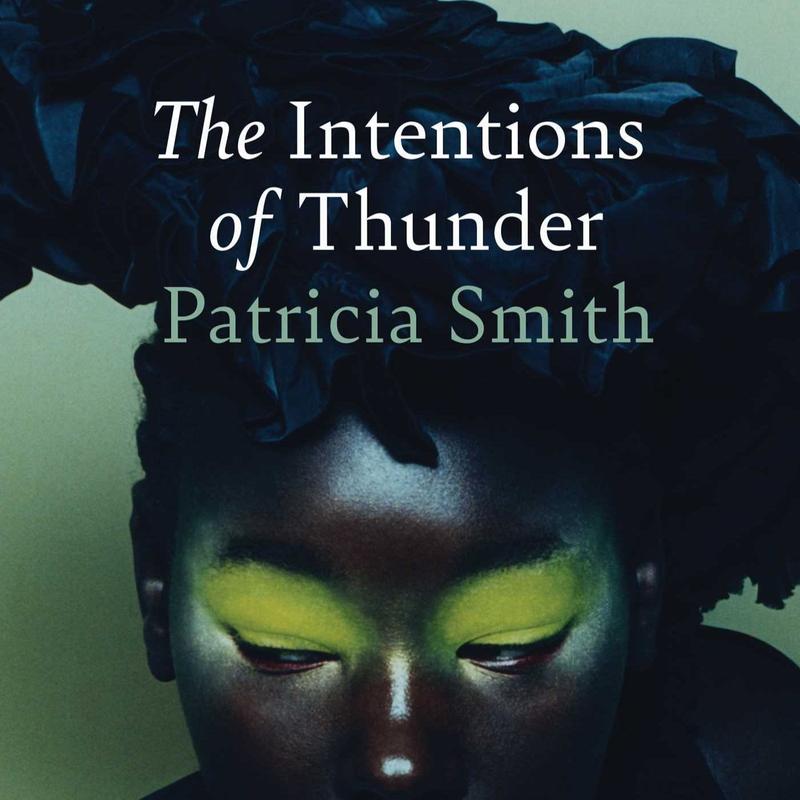

David Furst: This hour, the National Book Award for poetry was awarded to Patricia Smith, a Princeton professor and four-time champion of the National Poetry Slam. She won for her book The Intentions of Thunder: New and Selected Poems. The collection spans decades of Patricia's life and career, containing poems from 1991 all the way through 2004. Patricia writes about her family, about racism in America, about jazz and joy and history and current events. The Intentions of Thunder: New and Selected Poems is out now, and we are joined here in the studio by Poet Patricia Smith for a conversation and for some poetry readings. Patricia, welcome to All Of It.

Patricia Smith: Thank you. Very glad to be here.

David Furst: What does it mean, by the way, to win the National Book Award? What does that mean to you?

Patricia Smith: What does it mean to me? I got introduced to poetry by getting up on stage and doing it. For a long time, I was considered a performer, and for some reason, there was always--

David Furst: You were considered a performer, not a poet?

Patricia Smith: A performance poet, let's put it that way. For some reason, there was always this imaginary chasm between the so-called academic poets and the street or performance poets. For a long time, I was bound by that until I realized that we were all doing the same thing. To come from doing that in a smoky jazz club in Chicago for years to being up on a stage with some of the most premier poets and people that I used to be in awe of was absolutely amazing. That, along with the book where I went into some old books, it's selected, so I had to choose some of the poems from my other books. I relived all those moments, and I could see the trajectory. It felt absolutely amazing.

David Furst: I want to talk about that span there? The poems in this new collection go from 1991-

Patricia Smith: I was a child.

David Furst: -to 2024. Let's talk about what was going on in your life in 1991, and looking over that time, how do you think you've changed as a poet over 30 years?

Patricia Smith: I can point to something that happened at the beginning. There was a friend of mine who heard that there was a poetry program going on for five hours in a winter afternoon in Chicago. Of course, you're trying to get indoors in Chicago anyway, in February or whatever.

David Furst: I see, just be inside.

Patricia Smith: Right. There were 50 poets, and I said, "Wow, there's this fantastic literary community in a place where I grew up, and I didn't know about it." I went to this thing, and to tell you the truth, I was just going to laugh at poets. I didn't know anything. I just thought, "I'll go in, they'll read something about a flower growing through concrete, and I'll laugh, and it'll be great." I found out that there was this amazing community. Gwendolyn Brooks, our Pulitzer Prize winner, was still was there. She was encouraging the younger poets.

I got involved simply because it seemed to be the place to be. A place called the Green Mill was my home for years. It's a jazz club where supposedly Al Capone shot the piano player because he didn't like the selection. That kind of jazz club. I was there for years and years. That's where my ideas about what poetry should be, my ideas about audience-- I've never thought, "Well, I'm the poet, you are the audience." I think I'm not doing anything that anyone else can't do. I'm trying to grow the community of witnesses. I want people to hear me and then run off and grab a pad and a piece of paper and start telling their own stories.

David Furst: Do you think that your work has changed over time when you look at the earliest work and you look at some of the later pieces in the collection?

Patricia Smith: I think because in the beginning, I was just trying to get it on page so I could get up on stage. I knew nothing about line breaks or when to break for stanzas. I was just writing it all down. If you looked at something I wrote at that time, it would look like a stream of consciousness. It would not look like a traditional poem. When I decided that I wanted to learn the mechanics of poetry, I went to an MFA program. I learned meter, I learned form. Now I have a toolbox, because I'm a firm believer that the poem will tell you how it wants to sound.

I have now options. "Oh, I need a lot of repetition. This form will do that." In that way, I think my poetry has gotten more structured. The most exciting thing to me is to put a wild, unwieldy poem in a tight structure and feel that tension.

David Furst: Oh, that's really interesting, so that you can really play with that tension.

Patricia Smith: Right. You learn everything, so you can learn to break rules. That's what it's all about.

David Furst: Nice. Now, what was the process like, by the way, going back through all of these years, 1991 through 2024? You're not somebody that shies away from some very difficult experiences and topics, and you're revisiting all kinds of things during that time period.

Patricia Smith: At the beginning, it was more of a recreational exercise, and then I realized, A, I'm going to write to move myself sanely from day to day, and I'm going to write to let other people know that they're not alone. Going back in, there were things that I wrote and said, "Oh, thank goodness I'm on the other side of that now. I've written through it. I've gotten to a better place in my head about this." Then going back in was like I would say opening a wound, but in some instances, it's revisiting something that was happier. I did have to go back in.

I remembered walking to my keyboard with the feeling. I remembered how I wanted to feel when I was done. I remember what sparked the poems in the first place. It was difficult in some ways, but I learned a lot about myself because usually a book comes out and you read from that book until the next book comes out, and you move the older books farther into your past. Going back into some of those books put me right back in the moment I was in when I was writing.

David Furst: Can we hear some poetry here?

Patricia Smith: Sure.

David Furst: Maybe one of your earlier pieces, Doin’ the Louvre? Is that one you could do?

Patricia Smith: I can do that one.

David Furst: Talk about what this is.

Patricia Smith: One of the first trips to Europe I took as a poet was to Paris, and I'm just a little girl from the west side of Chicago. I had never been-- I'm there with a friend of mine, and we're running around, and we're in the Louvre, and we're pouring at things, and [onomatopoeia] because most American tourists like to pretend like they know everything already. "Oh, that would be the blah, blah, blah, blah, blah." We were just like, "The joy of discovery. This is fantastic." It's a poem that I wrote because I want people to remember what was it like when you did that for the first time, before you got jaded and numb to it? Ready?

David Furst: Yes.

Patricia Smith: This is for my friend, Patricia Zamora.

[POEM- Patricia Smith: Doin’ the Louvre]

You're a junkie, just like I am

After we dump your husband in the Louvre's cafe to sip the steaming tea and chew on his poetry,

we're off like schoolgirls screeching in duet,

dazzled by the bright eternal gasp of ancient things

We've got no business here, homegirl and compañera

We've got no business closing our mouths around this sharp, exquisite language

Or savoring the sweet tongue squeeze of pastries, shining cakes, and shaved chocolates.

We're of simpler stock, city and country dust, collard greens, moon pies, bullet holes, and basement slow dances

We are shamelessly American, rough street girls with rusty knees,

the flip side of Parisian wisp, in slim cashmere coats, the color of tobacco

Girlfriend, you and I are too much scream for this place

But you're a junkie, just like I am

Too long denied access to official beauty

We walk these streets with our mouths open and faces tilting up

Much too much scenery and sound for our thin American throats

We gawk at cathedrals with their gargoyles bleached to an eerie snarl by bright slashes of moon

Say goodbye when we mean yes, Good morning when we mean how much?

Ask for bread when we need the toilet

We are amazed that no one is asking for all of this back, that we are allowed to bask in this city's light

I can still hear my mama as plain and practical as a cast-iron skillet

Child, you need to stop all that foolishness over there in some France where you don't know nothing or nobody

Ain't no Black folks over there, no way

But I know you, old friend, with your bright burnished tangle of hair and deep laugh

And right now these halls belong to us

There are bad girls loose in the Louvre

Girls soft as gunshots,

Girls nourished and fueled by silvers, silks, and the stone gaze of Napoleon

We laugh at the smashed noses of Egyptian rulers

Stare at the tiny mummified feet of a young girl

Mistake Goya for Gauguin

And rub what surfaces we can

When we say things like, "Hey, I think I saw this on a postcard once,"

Or "Do you know how old this thing is?"

How can the world help but love us?

We would give Venus our arms.

After seven hours clicking our hungry heels and snapping illicit flash photos in dark halls brimming with whispered music,

We finally find the Mona Lisa alone,

Caged in antiseptic behind that glass every woman wears

And we wonder how best to free her, knowing she's a junkie just like we are

She longs for our wild voices, our naive, accidental beauty

She's aching to ditch that frame and skip these hallowed halls with the home girls

Mistake the obscene for the exquisite, and gaze at unsolved mysteries that just for once are not her own.

David Furst: Doin’ the Louvre.

Patricia Smith: Doin’ the Louvre.

David Furst: From 1991.

Patricia Smith: That's a long time ago.

David Furst: You can find that in the new collection, The Intentions of Thunder. Patricia Smith, poet, is with us today. New and selected poems collected in this running from the years 1991 all the way through 2024. Quite an arc of time covered during this. It's really fun to hear one of these really early poems and what you're capturing there. Maybe you could talk about that one line. You come back to it, I think, three times during the piece.

Patricia Smith: Oh, "You're a junkie, just like I am."

David Furst: "You're a junkie, just like I am."

Patricia Smith: I am from Chicago. I am a product of the Chicago public schools, and everybody from Chicago knows what that means. I'm an only child. I did a lot of gathering of things that I thought were worldly. Pictures, things that I cut out of magazines. This is what I'm striving for. I want to see this in a person one day, never really thinking it was going to happen. I was a collector of places I wanted to be and things I wanted to see. When I say, "You're a junkie, just like I am," she was the same way. We got there, and we started--

David Furst: Your friend was the same way.

Patricia Smith: Patricia Zamora was the same way. She was Puerto Rican. We were like, [onomatopoeia], and all of a sudden, there we are.

David Furst: A junkie. A lover of things.

Patricia Smith: Right. Yes, a lover of things. A collector. "I want all of it, and I want it right now." That kind of thing.

David Furst: Art, music, experiences.

Patricia Smith: That's it. I'm still that way. As a poet, I'm always looking to collaborate with musicians, filmmakers, dancers. The arts are always speaking to each other, and we put them together. I'm in a perfect place right now. I work in an art center. I get to do poetry everywhere that I go. I get to teach it. I do workshops. I do readings. I'm surrounded by what I'm most impassioned about, and that's how I want to live my life.

David Furst: You dedicate this new collection, The Intentions of Thunder, to all of your teachers. There's a list right at the very beginning, and you are a teacher, a professor yourself. Can you talk about the value of teachers in our lives?

Patricia Smith: The value of teachers. Speaking as someone who spent a lot of time searching for her fifth-grade teacher, I went to a school where we were expected to fail. Everyone was expected to fail. For the first time, I had a teacher look at me and look at something that I had written and tell me, "You were meant to do this. Whatever we need to do, you need to keep writing." Then I had some of those other teachers after that, but I always, always remembered that.

I remember the day that I-- You graduate from fifth grade because you go on to middle school. I walked across the stage at that graduation, and my fifth-grade teacher was on her knees with her arms open to greet me. I call upon that feeling a lot because if it had not happened, it would be so easy to talk me into, "Okay, your life is preordained. You grew up in this place. You grew up around these people. You grew up in this, so just face it, you're not going to make it."

David Furst: You're talking about it now.

Patricia Smith: Yes.

David Furst: When a teacher in fifth grade says something like that, what power does that have?

Patricia Smith: It was amazing. My dad, I had told him early on that I wanted to write. Even in my own family, my mother said, "Oh, well, only white men do that." Anytime I found something that aligned with my burgeoning dream, I clung to it and said, "Okay, even if nobody ever reads it, I know I'm going to write." I loved the idea that the canvas is clear every day, and you can just fill it with whatever story is pushing at you at the time. Now I do it for a living.

David Furst: What would you say to someone listening, maybe right now, who is an aspiring poet but perhaps doesn't feel confident yet in their writing? What message would you have?

Patricia Smith: It's the same thing as if I were to go into a school and have a child tell me, "I can't write poetry because I'm a bad speller." Poetry is something that belongs explicitly to you. No one has to see it. It could make you move from one place in your head to a safer place, to a stronger place. My thing is something that I didn't have much when I started, but you can now go online and hear everybody from Robert Frost to Gwendolyn Brooks to hear them read their own poetry.

I think the first thing I would do is say, "Don't think of yourself as a poet. Think of yourself as a storyteller. You're choosing poetry more often to tell those stories," because we are all storytellers and the idea that our stories are worth it, that'd be the first thing that I would get across, that no matter where that story begins, where it be plays out, it's always worth it.

David Furst: We listened to you read a poem from the very beginning of this book, an early one. Can we hear a more recent poem? I was thinking about one that comes very near the end of the book. It's called What Daughters Come Down To. This comes from the section of the book collecting works from 2010 through 2024. Is that one that you could do today?

Patricia Smith: Surely I could do that. There is something I want to tell you about this one.

David Furst: Yes, tell us.

Patricia Smith: I'll wait till I'm finished.

David Furst: Sure.

Patricia Smith: What Daughters Come Down To.

[POEM- Patricia Smith: What Daughters Come Down To]

For what I'm sure is the fifth time,

my mother plugs in a flat mournful hum where the words I love you too, should be

Then she hangs up without saying goodbye

I squeeze my eyes shut,

try to imagine 82 autumns in the bones in her rasping joints,

In the cool jaded thump of what is still a migrant's ever-arriving heart

However, I believe she is required to love me

I wonder what God was teaching her all those years,

Those day after days coaxing raucous hips into deadening girdles and gray A lines

So she could lose her mind to organ

Was it all theater, a screeching of north when south was what itched her?

All of it. Mock belly, the nails splinter, spewing cross,

some sly spirit habitually overloading her spine,

making her dad thirsty and unfolded

How could all those rye hymns and hot sauced hallelujahs lead to this hum, clipped, connect, and hush

I am hundreds of miles away, but I can see where she is sitting, hands still on the phone

Every surface in her tiny apartment is scoured and bleached

Draped in a disinfectant meld of rain, shower, and blades

The kitchen glints

Jesus's searing blue eyes looked down on everything

Her rugs are faultless

The purpled tulips I have sent for her birthday are insistent feral beauty,

A blood in the room

Like her daughter, they have bloomed in the clutches of vapor

I love you, too, she thinks out loud, but can't.

David Furst: What did you want to share about that poem?

Patricia Smith: One of the things when you asked me how my poetry had changed throughout the years, I think that some of the things that I attempted to address, family things, loss, heartbreak, all those things, when I tried to address them earlier, I didn't have the tools or the courage to do so. I think the longer I wrote, the more I realized that I was telling my own life story and that there are a lot of things in that story that other people go through. We tend to clutch our secrets.

The minute you bring something out into the air as "Oh, I didn't have a great relationship with my mom," other people come up to you and say, "Oh, my God, me too." That idea of growing the community of witnesses and having people say, "Oh, I can write about that. I can meet other people who have gone through that." It's a really big responsibility in poetry now that a lot of people who don't write poetry or even really listen to it that much are hungry now. They're coming into these audiences, and they're looking for someone who lives a parallel life. They're looking for a guide.

Truth is in such short supply lately that people are now turning to the poets and saying, "Oh, what's going on over here? What are they saying?" When we're writing about serious things, we owe it to those people to give them a lifeline, something they can reach for.

David Furst: It's a powerful juxtaposition in this piece, between the lines, someone whose rugs are faultless but who can't bring themselves to say, "I love you, too."

Patricia Smith: The cleanest woman in the history of the world. My mother was always very businesslike and such a contrast with my dad, who was funny and told stories and sang badly and did all that stuff. There's something that I got from my mom, but if you look at me now, I'm all my father. I can't sing either.

David Furst: There's a lot of great work in this book about music and history, your mother, your father, son. It's an incredible collection. Again, it spans the years 1991 through 2024.

Patricia Smith: You're just going to keep saying that, 1991.

David Furst: It's amazing to me. Patricia Smith, thank you so much for joining us today-

Patricia Smith: Sure. It was a pleasure. I really appreciate it.

David Furst: -and for sharing your poetry with us. You were a professor at Princeton, a four-time champion of the National Poetry Slam. The most recent book is The Intentions of Thunder: New and Selected Poems. Again, thanks for joining us.

Patricia Smith: You're welcome.