Love & War' Follows A Photojournalist On The Battle Front, And The Home Front

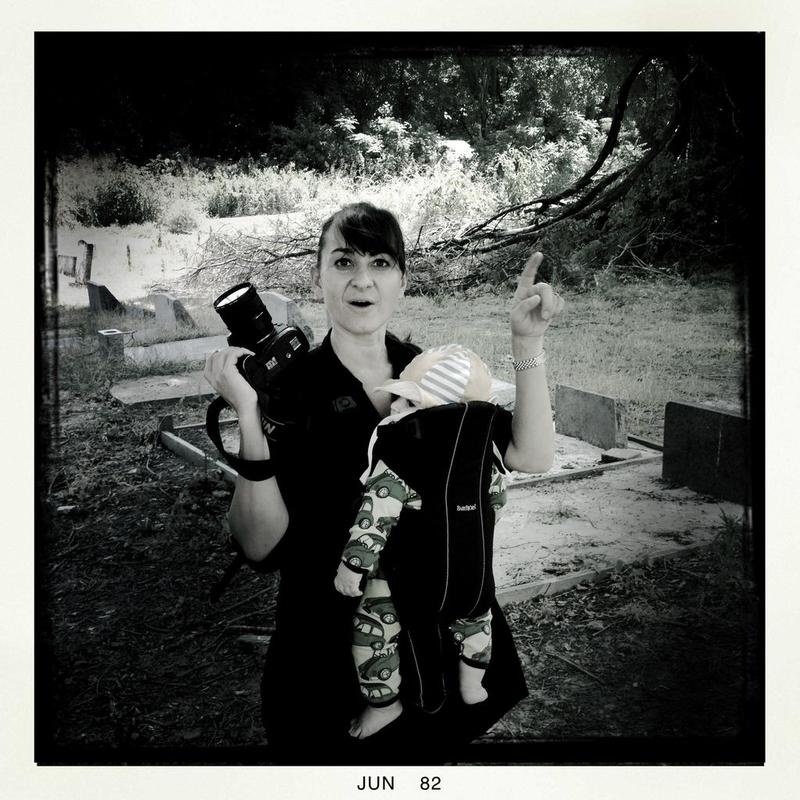

( Photo courtesy Lynsey Addario )

Alison Stewart: This is All Of It on WNYC. I'm Alison Stewart. Lynsey Addario wears many hats. She's a sister, daughter, wife, mother, and one of the world's leading conflict photographers. She's worked in at least 12 war zones from Afghanistan to Libya, and has won the Pulitzer Prize for her work. Her work led the world to see on the front page of the New York Times that Russia was indeed targeting civilian populations in Ukraine. Her job is intense, dangerous, and the hours are long.

She's exposed to the horrific violence on a regular basis, and she still flies home in time to make it to her kids' recitals. Her marriage is often strained from her commitment to her job. All of this is shown in a new documentary premiering on National Geographic tonight and streaming on Disney and Hulu tomorrow. It's called Love and War. We see Lynsey in bulletproof vests and helmets taking photos. The shelling of civilians in Ukraine, the maternal health crisis in Sudan. The moments before she and her team were kidnapped in Libya. Here's a clip from Love and War, and in it we hear not only strain on her career and how it puts on her family, but in some ways how family strains her career ambitions. Let's listen.

Alfred: Where's my mommy?

Paul de Bendern: Mummy is working, Alfred.

Alfred: Is it downstairs?

Paul de Bendern: She's in another country, but she's going to come back soon. It's the length of assignments. That's always been the challenge in our relationship. If it's one week, two weeks, it's not really a big deal, but when it gets longer, over three weeks, as always, things tend to unravel at home.

Lynsey Addario: In my heart, all I want to be doing is shooting. It's frustrating. I'm constantly tortured, like I'm not in the right place, but I come back, I'm supposed to be really happy. I feel like I should be there, and I feel like a bad journalist because I'm not. My head is always where I'm not.

Alison Stewart: Lynsey Addario is in studio with me now. It is nice to see you.

Lynsey Addario: It's nice to see you, too.

Alison Stewart: What was it like to be in front of the camera?

Lynsey Addario: I know the drill. For 25 years, I've been asking people to open up their lives to me, and I've been asking the world of them in their most vulnerable moments. I think when I accepted to be the subject of this documentary, I had to think about it before I accepted because I knew that if I said yes, I would have to open up my life. That would be the only way to do this in a way that would do justice to the profession and to people like myself. I'm a parent and I'm a wife, like you said, and a sister, and also a war photographer. I think that we often only see one side of that profession.

Alison Stewart: How did it come to be? How did this come to be?

Lynsey Addario: I've been asked a bunch of times to be the subject and sometimes as one of 10 photographers or part of a documentary. It's complicated. It requires not only me having advanced knowledge of where I'm going on assignment, but also asking my subjects to accept me into their lives, and also another camera, and often a crew. I've always shied away from it. I never felt like I was ready for that or that I merited being the subject of a documentary. Then I kept seeing all these renditions of war photographers, both in Hollywood fictional versions and also documentaries.

Often it was a man, or if it was a woman, I just felt like the personal life wasn't properly depicted, or there was no personal life, which is quite common in our profession. I just finally said yes. It was the right timing because it was right before the full-scale invasion of Ukraine. It all came together weirdly in those first few weeks of the full-scale invasion.

Alison Stewart: As I watch the film, I know a lot of wartime photographers from my previous life. Was your decision in part to document what you do for your children in case something happens to you?

Lynsey Addario: Yes, I'm always thinking about that. I'm always thinking about will my children ever understand what drives me and why I'm not home, and why I miss their birthdays and why I'm not at school when most parents are. It's complicated because I try to be honest with them, but they're young. Alfred's only six, and Lucas is turning 14 in December. Yes, one side of me thought, "This will live forever, and it will be something that they can watch and hopefully understand a side of me that they will never have access to."

Alison Stewart: I'm speaking with conflict photographer Lynsey Addario, who's subject of a new documentary premiering on the National Geographic Channel tonight called Love and War. What do you need to be a good wartime photographer?

Lindsey Addario: You need to be good with people. I think you have to really love people and be accepting and non-judgmental. I think that's when you get into deeper stories. I think to do this job, you have to be flexible with your timing and life, and commitments. You have to be aware of what's going on in the world, always paying attention. You have to be very creative about how you deal with authority, and also getting into places. I think people don't realize one of the hardest things about covering war is getting access to people and getting access to a location.

So often it's being dependent on NGOs or organizations that can get you to a place, or having a good network of producers or fixers on the ground, local journalists. Then you have to think quick and really be always on your feet, making contingency plans, "What happens if something goes wrong? How can I save my own life and save the lives of the people around me?"

Alison Stewart: Why is photojournalism so important today?

Lindsey Addario: I think it's more important today than ever because we live in a world where not only is journalism questioned, but truth is questioned, and photography is questioned. Photography used to be the be-all-end-all. If you have a photo, it means it happened. Now you see a photo and you think, "Is that AI-generated?"

Alison Stewart: I was going to ask you, what do you think about AI?

Lindsey Addario: I think it's amazing for all the many reasons, but it complicates the lives of all of us, who spend our lives going to very difficult places documenting situations, and then I come back, and then there's a composite image of a similar scene trying to pass as real. The fact is, most people check social media for their news source now, and they don't realize that you can't just follow anyone and take what they put on their feed as fact. We really have to be careful about where we are ingesting images from and information from, and understand, is it real? Has it been fact-checked? Who are these people? Are they journalists? Are they civilian bystanders? Who are they?

Alison Stewart: You shoot in color?

Lindsey Addario: I do.

Alison Stewart: Why do you shoot in color rather than black and white?

Lindsey Addario: I started in black and white. Now I'm really dating myself, but I started shooting, oh, dear, maybe 40 years ago. I shot on film and in the darkroom, and I loved black and white, but I think when I started moving through the world, and when we transitioned to digital after the attacks of September 11, and digital cameras became the expected and we had to file in real time, I really transitioned to color and realized that I see the world in color. For me, it's harder because it's--

For me, look, a black and white image is so dramatic, and you can do all these alterations with contrast and Photoshop and make it just look like it doesn't matter what light you're shooting in. You can just make any image look dramatic. On one hand, it's a lot easier to shoot in black and white, but for me, the world is in color, and I see the world in color, and I feel like that's how I shoot, except for a very rare occasion when I shoot a story and I just think, "Okay, maybe this is black and white."

Alison Stewart: Do you have an instinct for when something's going to happen?

Lindsey Addario: I do. I have a horrible instinct.

Alison Stewart: Tell me a little bit about that. The hairs on your arms go up? What happens?

Lindsey Addario: It's a process. For example, in Libya, where I was captured with three colleagues from the New York Times on March 15th, 2011. Leading up, I had been working on the front line in Libya for two weeks in very heavy combat, full-on gun battles and tank rounds coming in and airstrikes, and helicopter gunships, and literally trying to hide myself into irrigation ditches because the ground was so flat. I got to two weeks in, and then I just started to feel this thing like something's about to go wrong.

So much so that I took my hard drive of all my images and gave it to a colleague, Brian Denton, and said, "If I get killed or if I disappear, can you just make sure my photos make it to my agency?" Two days later, we got captured, and we had no idea if we would survive. The kidnapping in Iraq, I also just had this very weird premonition. I often have a premonition, but it doesn't mean it comes to fruition all the time. Sometimes it doesn't, and thank God.

Alison Stewart: What happens in your mind when you've been kidnapped?

Lindsey Addario: It's all about staying alive. It's all about trying to stay calm. For me, weirdly, I'm a very bubbly, loud extrovert, but when I'm in these horrible situations, I get very quiet and very focused, and I'm okay with just taking it minute by minute and saying, "Okay, I just need to get through this minute, and then the next minute." Minutes turn into days, which turn into a week. It's really just about survival. I think we as human beings have this incredible survival instinct. I think we have to learn how to rely on that and listen to that, because it does exist.

For me, luckily, it comes out when I need it to, and it's helpful because you have to stay focused and you have to stay calm when you're being kidnapped, essentially.

Alison Stewart: I'm speaking with photographer Lindsey Addario, who is the subject of a new documentary premiering on the Nat Geo Channel tonight called Love and War. It's about balancing her home life and her demanding and often dangerous career. During the film, we see you cry several times.

Lindsey Addario: A lot.

Alison Stewart: We see you cursing. Don't curse on the air, by the way, but you go at it a couple of times.

Lindsey Addario: Yes, sorry.

Alison Stewart: Please. It's actually reassuring because it shows us that you're human. You're not just a robot taking pictures. What are some of the other ways that you process the trauma that you see? We hear it, we see it, but there have to be other ways that you process it.

Lindsey Addario: Yes. I annoyingly started vaping in Ukraine because we were literally working all the time, and there was no outlet. We were always under fire the first seven weeks of the war. It was very, very intense. I exercise. For me, my exercise is like a release. It's something that's almost meditation for me. I work out generally 90 minutes a day. When I'm back in London, it's sometimes two hours a day. Wherever I find time, I exercise, and that really just grounds me, gets my endorphins going, and it keeps me happy and grounded. Then the other thing I do is I surround myself with amazing people that I love, friends, family. My parents, my sisters are incredible.

Alison Stewart: Your sisters seem pretty hilarious, and they're in the film. They are pretty funny.

Lindsey Addario: They're really funny, and that's them tame. When we get together over Christmas, you can basically hear us laughing down the street. We have a lot of fun together. I have an amazing family, and then my husband and my kids. For me, it's really about being present where I am and enjoying that moment.

Alison Stewart: One of the things that comes up in the film is that you and your husband have quite a bit of privilege, financial privilege, and you're able to be able to support people helping you out. Could you do this job without that kind of support?

Lindsey Addario: Without my husband's support?

Alison Stewart: Yes.

Lindsey Addario: It'd be hard. I've been doing this for 25 years, and I hustle. I work really hard.

Alison Stewart: You do.

Lindsey Addario: I don't rely financially on my husband to run my business, but certainly, the mortgage in the UK, that is something I probably couldn't afford. When we met, I was living in a tiny, little apartment for $350 a month in Turkey. I would probably still be living like that if I hadn't gotten married. I think it is a profession that no matter how long you've been doing it, the day rates don't change depending on your experience. I make the same per day as someone who's just coming into the profession. That's hard because I'll be 52 next week, and obviously, I have a lot more responsibility than I did when I first started.

Alison Stewart: How did you feel about being vulnerable about your relationship with your husband on camera?

Lindsey Addario: I felt like it was important. I'm a journalist, and I do not like when a subject is self-censoring. I feel like we would not have said yes, or we would just not have included any of our family life, because I think if you're going to open that door, just open it. I was lucky because my husband also used to be a journalist, and so he felt comfortable. He's also very self-confident. He's very grounded in who he is. I think we both are. I think we both believe in who we are, and that's important for a documentary in terms of opening yourself up, because I am vulnerable. I cry a lot more than I care to--

It's embarrassing how much I break down, but I have been doing this a long time, and I'm tired of seeing people suffer. It's hard. I guess I would be worried if I did not break down at this point, if I was so stoic that nothing affected me.

Alison Stewart: Has the documentary led to any interesting conversations in your family with your husband?

Lindsey Addario: We have these conversations all the time. It's a painful life. I think we constantly struggle with how long I'm away, how consecutively I take assignments. That's the other thing. I can do a two-week assignment and then come home for three days, and then another story comes up, and I have to leave for another two weeks, so it's a month. I think that's the other thing. The other thing I do to support myself are speaking engagements, and that cuts it. That also requires me to travel.

I'm juggling that. I'm writing another book. I'm doing a lot of things to make ends meet and to be able to do this work and to get the word out, essentially, but the conversations are hard because everything requires me to be on the road except for sitting down and writing, essentially.

Alison Stewart: We got a text here that says, "Love and War is a very powerful documentary. So engaging, amazing journalists. Lynsey has enormous courage." Do you think you have courage?

Lindsey Addario: I do not. Thank you. Thank you, whoever wrote that. I do not think I have courage, but I think that's because I'm surrounded by some of the bravest people on the planet. I'm usually photographing women in Sudan or who have just fled to neighboring Chad with their kids on their back, watched people die along the way, perhaps were survivors of sexual violence, and they continue to stand on two feet and be proud and tell me their stories with the hopes that their stories can help in some way. I'm always surrounded by incredible people who live in war constantly and have no escape.

Alison Stewart: I wanted to ask you about maternal healthcare in Sierra Leone. It's a story that struck with you, but you also changed policy with the work you did. Would you tell us a little bit about that?

Lindsey Addario: In 2009, I won a MacArthur Fellowship, and I really thought about what I could do with it. At that time, maternal mortality rates were-- over 550,000 women a year were dying in childbirth, which is extraordinary because most of those deaths were preventable. I basically went to Sierra Leone. I went to one of the provinces with the highest maternal death rate in 2010. I went to the maternity ward. I met this young woman, Mama Sise. She had been pregnant with twins, delivered the first baby in the village. The second baby wouldn't come out, so she took a canoe across the river to an ambulance, and then six hours across bumpy roads.

I talked to her at length. When she got to the hospital, she was rehydrating and we were talking, and when she delivered the second baby, she started bleeding. I was shooting some video and stills, and I'm saying, "I think she's bleeding too much." The midwives were just mopping up the blood. I said, "Is there a doctor?" The midwives just laughed at me, and they were like, "Well, there's one doctor in the whole province. Good luck." I ran to see if I could just get him there.

Sometimes, as a foreigner, you're able to break through. I ran into the surgical ward, put on scrubs, everything, and I said, I think there's a woman dying. He was obviously busy. When he came out, they had carried Mama Sise to right outside of the surgical ward, and he pronounced her dead. She died. I published this story across eight pages in Time Magazine in 2010. One of the board members from Merck, the pharmaceutical company, saw the story and apparently showed it to a bunch of board members during their meeting for corporate responsibility.

They were talking about how to spend money. I don't think it was the only reason, but certainly it impacted their decision to start Merck for Mothers and put aside $500 million to fight maternal death. The rates have gone down. They halved. Maternal death rates are about 220,000 women a year now, I think, or about half of what they were.

Alison Stewart: In our last moment, as someone who truly believes in journalism and the moment that we are in and the moment that journalists are faced, what would you say to someone who has a lack of confidence in journalism right now, might want to get out of the business? "I've had it. I'm not doing it anymore."

Lindsey Addario: A journalist?

Alison Stewart: Yes.

Lindsey Addario: I would say we need you. I would say the world needs freedom of speech, freedom of the press. We need journalism more than ever. I think that the fake news, all of that, it does a real disservice to a democracy. I think we have to work hard to make sure our stories are airtight and factually correct.

Alison Stewart: I have been speaking with conflict photographer Lindsey Addario. She's the subject of a new documentary premiering on Nat Geo tonight called Love and War. It's balancing her home life and her demanding and often dangerous career. You can also watch it streaming on Disney and Hulu tomorrow. Lynsey, thank you so much for being with us.

Lindsey Addario: Thank you so much for having me.

Alison Stewart: There's more All Of It on the way.