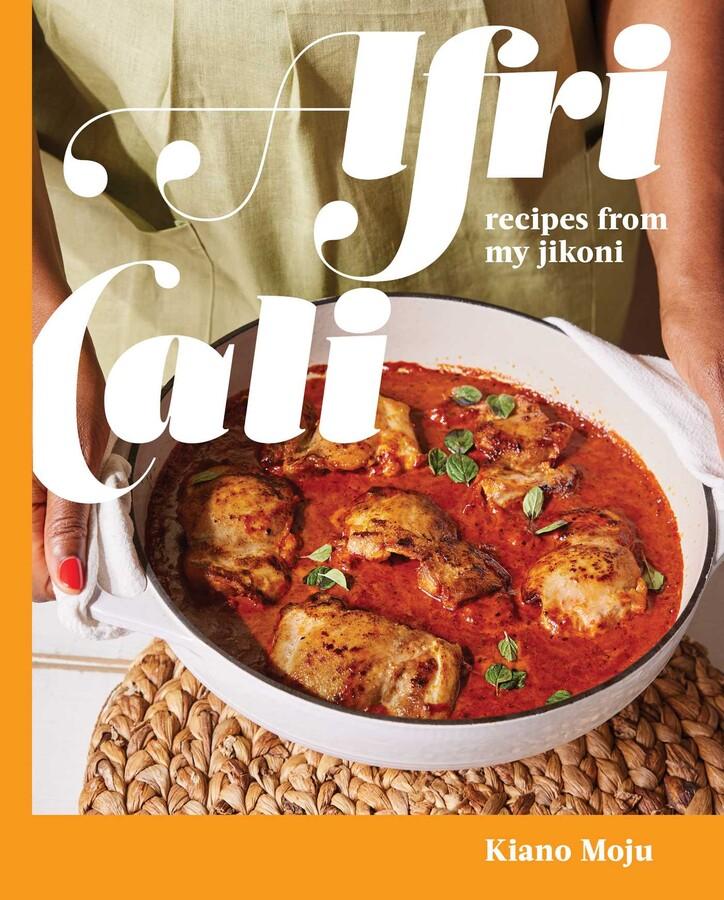

Kiano Moju's Cookbook AfriCali: Recipes from My Jikoni

( Courtesy of S&S/Simon Element )

[music]

Kousha Navidar: This is All Of It on WNYC. I'm Kousha Navidar, in for Alison Stewart today. In her cookbook, food writer and recipe developer Kiano Moju writes, "When someone learns that I cook, the first question is always one of two: what's your signature dish or what kind of food do you cook?" AfriCali really sums it all up. Filled with inventive collections of more than 85 vibrant and modern recipes, her debut cookbook bridges the traditional flavors of Africa, with the freshness of the West Coast. She includes dishes, such as chili cheese, Pommes Anna, red pepper vodka chicken, Berbere-braised short ribs, and desserts like green mango, olive oil cake, and passion fruit and lime pie. It all sounds so delicious. The book is called AfriCali: Recipes from My Jikoni, and it is out now. Kiano Moju joins us today to discuss. She is a food writer, recipe developer, and video producer whose work has been featured on major platforms like BuzzFeed's Tasty and Food52. Kiano, welcome to All Of It.

Kiano Moju: Hi. Wow, you just rallied off all my favorite things in one go.

Kousha Navidar: Well, happy to put them out there. Listeners, we would love to hear from you. Are you Nigerian or Kenyan, or have you tried West African or East African cuisine? Tell us your favorite dish. Do you enjoy eating jollof rice, pilau, chicken yassa, or fried plantains? Have you seen Nigerian or Kenyan cooks living in the United States put in American spin on a classic West African or East African dish? Or what questions do you have for Kiano about developing new recipes?

Call us or text us. We're at 212-433-9692. That's 212-433-WNYC. Or you can reach out to us on social. We're on Insta and we're on X. Our handle is @allofitwnyc. We're taking questions, and we're just spreading the love about West African and East African cuisine, so be sure to call in.

Kiano, how did you come up with that title, AfriCali: Recipes from My Jikoni?

Kiano Moju: It was actually the other way around. My publisher flipped it, which I think was a brilliant move. I initially wanted to call the book, Jikoni: Recipes for My AfriCali Kitchen. I think the term AfriCali jumped out at him. It's not a word I made up. It's been used in music for a few generations now. When I first learned about the term, I think probably a couple decades ago, I immediately connected with it, because I'm like that. That's is literally me. [chuckles]

Kousha Navidar: Jikoni, can you talk about that a little bit?

Kiano Moju: Yes, Jikoni is Swahili for kitchen. My mother, she's from Kenya, where Swahili, along with English, is our national language. I like to bring in some of those terms as much as we can. I think we all got a dose of it when we were kids, watching The Lion King, with words like Simba and Mufasa. These are all Swahili words, but I don't think we've had any come into our rhetoric since. If I can slide one more in there, that'd be great.

Kousha Navidar: Jikoni means kitchen. That's wonderful. How did you want this book to reflect not just your upbringing that you touched on a little bit, but also the recipes that you've learned over the years?

Kiano Moju: Yes. I grew up in the East Bay area, so in Oakland, California, and I ate everything. I would eat food at home. My mom would cook amazing Kenyan food on the weekends, but we were maybe more than we should have dining out. We were eating, picking up Ethiopian after school, eating Vietnamese food. When I started cooking, like anyone else, I just started cooking what I enjoyed eating. These flavors, they naturally came together because I am a big proponent of cook what you got, and I don't like hustling too hard. Even when writing this book, I did all the grocery shopping at the stores around the corner from me. We don't have to hunt for ingredients to make really delicious food.

Kousha Navidar: When did you become interested in making food your career?

Kiano Moju: Oh, I was dreaming. From really young, I would sit, wake up Saturday mornings and watch cooking shows, and I started cooking really young. I think when I was six, seven, my mom put me in cooking class. I would be in the kitchen making stuff, talking out loud, like, now you're going to add a dash of sugar, as if I was on a cooking show. The passion has been there very long, but it wasn't until I finished my undergrad, pre-law, where I was like, let me just see if I can have a career in this before I go to law school.

Kousha Navidar: What was the moment where you kind of knew, yes, this is the path forward for me? It's what I want to be doing. Sustainable, of course. I'm sure, like, thinking about making the career out of it. Was there a moment where it really came into full force for you?

Kiano Moju: Yes. I think it was-- I went and did my masters in publishing in London, over in the UK, and while I was doing that, was interning, and I think it's once I stepped foot into a space, it was a magazine called delicious magazine. I was interning there. Everything I had thought of and wonder about was real, and I was standing in the room, and I was like, oh, these are just people doing their job. It's a lot of computer work, more than people think. Then a couple times a week, they test recipes and feed everyone. I was like, okay, I can do this.

Kousha Navidar: What's one dish that often reminds you of family and of home?

Kiano Moju: Oh, it's going to be so simple. There's two recipes in the book. One is it's called Koko's Cabbage. Koko is a name for my grandmother. She has just a very simple way of just sautéing cabbage with carrots, salt, cilantro, onion. That's it. It's so simple. She always serves it with a flatbread we eat in Kenya called chapati. It's like very tender, flaky layers, and just eating that bread, tearing it up, scooping up that slightly sweet sautéed cabbage. It looks so bland and boring, because just like beige sautéed cabbage and bread, but it is delicious, and it reminds me of my childhood, and it's just really good.

Kousha Navidar: Can you talk a little bit about what makes the cuisine that you're writing about, the culinary traditions, unique? I'm thinking Nigerian, Kenyan, if you have to describe it both in the ingredients, like you're talking about, and also in types of preparation. Is there a way to give a top line view of that?

Kiano Moju: Yes. The two cuisines of my parents, my mom from Kenya, dad from Nigeria, probably have more differences than they do similarity. They are, like my mom's family are cattle ranchers. My dad's family live off the riverbanks. So even just ingredients are on different ends. What I decided to do with this book is curate those dishes that focus on what are really global ingredients, onions, tomatoes, a little bit of meat, because I would say Nigerian food, more so than Kenyan food, has very specific regional ingredients. Unless you have a West African grocery store right next to you, but also the Internet has opened up the doors to everything. Not all of those ingredients. You can just, on a whim, be like, let's go cook this tonight and go to your local store and do it.

There are some dishes that fit the bill, and so those are the ones that are in the book. You'll see that even though some of these dishes have different names like egusi and bajiyas, once you look at the ingredient list, everything is going to look super familiar to you. It's really finding what ingredients we all have and we all have access to, and then presenting new ways of cooking them by looking at how these ingredients are combined within these countries.

Kousha Navidar: Right. You're talking about finding ingredients as a way of making the recipes you wanted to share more accessible. Some people find cooking intimidating, just the idea of cooking, and I think that idea of accessibility is really interesting, like how to make it approachable. What was your approach to writing this cookbook to make it more accessible, beyond ingredients? Were there certain techniques that you had to break down or think about how to offer in an interesting way, or did it come through in other ways for you?

Kiano Moju: I am a home cook by trade. I've never worked in a restaurant in my life, and my entire career, I'm writing recipes for home cooks. Besides it being an easy grocery shop, it's also like, okay, how much time am I going to spend standing in the kitchen right now? That means being efficient. If you've read a recipe written by a chef, there's something called mise en place, where they have you chop up everything, get it ready, and then you start cooking. There's never been a chapter of my life where I have time for that [chuckles]. I am very much pro let's cook, let's get something on the stove ASAP, and then while that thing is doing its thing in the pan, let's chop the next thing.

Sure, you might have a little risk of charring something, but that is part of the world of home cooking. It doesn't have to be perfect, but I do like to be efficient in the kitchen and how you spend your time in the kitchen. That is something I kept in mind when writing up these recipes of, like, how can I get you in there and out there in the best amount of time I can, while never sacrificing flavor, because we can take shortcuts, but if the shortcuts leave to flavorless food, we can't go that route.

Kousha Navidar: Listeners, we're talking to Kiano Moju, the food writer and recipe developer. We're talking about her book AfriCali: Recipes from My Jikoni, which means kitchen. We are taking your calls and your texts. We would love to hear from you. Are you Nigerian or Kenyan, or do you want to shout out your favorite dish? Do you enjoy eating jollof rice or pilau or chicken yassa, fried plantains? What is your favorite element of this cuisine? Give us a call or send us a text. We're at 212-433-9692. That's 212-433-WNYC.

One of our producers in the channel right now just said, "I'm so hungry." I think this is getting around to ears and tummies around the listening area. We have a good text here. It says, "My favorite is Kenkey." Am I pronouncing that right? Kenkey?

Kiano Moju: Kenkey.

Kousha Navidar: Kenkey. Made by the Ga people of Ghana. It is slightly fermented corn steamed in corn leaves and eaten with stews, soups, or simply fried fish with a special dip made of pepper, tomato, and onion. It can be purchased at specialty stores in American cities, the Bronx, North Philadelphia, Chicago, Watts, or Compton. Thanks so much for that call out.

Let's get into some of the dishes that you have in here, some of the recipes. We mentioned jollof rice a couple times, which you have a recipe for, specifically Nigerian jollof rice, but each West African nation has its own recipe. Can you give us the history of that a little bit, what the foundation of every recipe is that you would find for that dish?

Kiano Moju: Yes, I mean, like any-- I don't think there's a dish in the world where the origin is not contested. I'll go with the version that I've learned that feels the most plausible, where the concept of this dish of rice that's cooked in a very flavorful, typically tomato-based stew originates from the Senegambia region, so Senegal, Gambia. Other West Africans learned and saw this rice, and like, oh, that rice of the jollof people make, it's really, really good. We should all and everyone made their own version of a jollof rice. In Senegal, where the dish origins from, it's not even called jollof, because it was their OG. It's called Thieboudienne.

Kousha Navidar: What's it called? Can you say that again? I didn't hear it.

Kiano Moju: Thieboudienne.

Kousha Navidar: Thieboudienne?

Kiano Moju: Yes. I think everyone just made their own version, like we normally do. What ingredients are frequently found in your local market, and how can you make your own version of jollof? The Nigerian version is rice that's cooked in a tomato and pepper-based stew. In Nigeria, it's a pepper called tatashe, which we ain't got that. I haven't seen that type of foods, but we have red bell peppers, which are pretty similar. You blend that up with some chili, habaneros, scotch bonnet, some onions. You can use garlic, ginger, and then for us in the US, it's going to be like, oh, that's tomato sauce or tomato pepper sauce. In Nigeria, we call it stew. It just gets cooked down really thick like you would your Sunday gravy. Add some seasoning, and then you cook rice in that with some broth. A lot of deep flavor, and it is a staple, but it is highly contested who makes the best one, which honestly doesn't matter. They're all so different. There's a different race for a different day. As someone who's Nigerian, Nigerian jollof is when I had to put in the book.

Kousha Navidar: Absolutely. Let's go to a caller. We've got Abby in South Orange, New Jersey. Abby, hey, welcome to the show.

Abby: Hi. Thank you.

Kousha Navidar: Go ahead.

Abby: Yes, so I would say my favorite African dish is from Ghana. It's called Waakye. It's essentially red beans and rice dish, which has a lot of condiments, such as stew, eggs, and salad with it. It's absolutely delicious.

Kousha Navidar: Wonderful. Thank you so much for calling, Abby. Waakye, it is red beans and rice from Ghana. Thank you so much for that call. Looking at the clock, we got to take a quick break. We'll be back in a moment. We'll be talking more with Kiano Moju, the food writer and recipe. Going to plug the book again, AfriCali: Recipes from My Jikoni. Listeners, if you have a dish you want to call out, if you love Nigerian or Kenyan cooking, or if you have a question for Kiano, tell us on the phone. Give us a call. We're at 212-433-9692. That's 212-433-WNYC. I'm going to take a quick break, and when we come back, more calls and more recipes. Stay with us.

[music]

This is All Of It on WNYC. I'm Kousha Navidar, and we are talking to Kiano Moju, the food writer and recipe developer, about her book, AfriCali: Recipes from My Jikoni. Listeners, we would love to hear from you. Are you Nigerian or Kenyan or have you tried West African or East African cuisine? Tell us your favorite dish. Do you enjoy eating jollof rice, pilau, chicken yassa, fried plantains, egusi. Give us a shout. Tell us what you love. We're at 212-433-9692. Let's go to some calls. We've got Karen in Montclair, New Jersey. Hey, Karen. Welcome to the show.

Karen: Hi. Thanks for taking my call.

Kousha Navidar: Absolutely.

Karen: I'm really enjoying this show. I concur with the writer when she talked about jollof rice being a basic rice-based dish. I have sister-in-laws from Liberia, and they cook a version of jollof rice. I'm originally from Guyana, South America, and we cook something called cook-up rice, which is similar to jollof rice. As I told the screener, I've been eating plantains all my life. On the PBS cooking show, I recently saw a Nigerian cook, making sweet plantains in a totally different way. She had a ginger-based sauce with that plantain. If the writer knows about that, if she can talk a little bit more about that, I'd appreciate it.

Kousha Navidar: Sure. Karen, thank you so much for that call. Kiano, listening to Karen, what comes to mind?

Kiano Moju: I'm trying to think. I think it could also be-- There's a couple different pepper sauces. It's an iteration of this stew base that's used for jollof rice. It's called Obe ata, and it can be transformed into a condiment. I'm curious, Karen, if the sauce was red, or if it was gingery, like tan colored.

Kousha Navidar: Can we get Karen back on the line to see if-- Karen, are you there?

Karen: Yes. It was gingery, tan colored. She blended ginger in some other spices in a blender, and then tossed the cube plantains in there, and then I think she fried it.

Kousha Navidar: Okay. Kiano, any sense?

Kiano Moju: He's doing some new stuff, and I love to hear it. Here's the thing about food. When we think of what traditional dishes are, I don't know, when the cutoff point was between what is considered traditional versus new school, but it sounds like it's a new school dish, but also, I'm going to immediately look that up because I think it sounds delicious.

Kousha Navidar: Yes, and Karen, we really appreciate you calling and letting us know. I love to hear moments when cuisine finds relationships, if you go deep enough into its roots. One example from your book that really struck me when I was reading, Kiano, was samosas. Some listeners might be unaware that samosas are common in Kenyan cuisine, but these often require a lot of work. Can you talk to us a little bit about it? How much work does it take to make samosas? What are some common fillings in Kenyan cuisine?

Kiano Moju: Yes. Samosas are so common in Kenya, I don't think there's a restaurant where you can't order them. There's gas stations. If you've had samosas via India, the Kenya ones are going to be a little different. They're in a very thin pastry, similar to what you would have if you were getting, like a Chinese egg roll. It's like that very thin, crispy pastry, and most commonly done with seasoned ground beef. Then we don't do sauce because everyone's always asking me, what's the sauce? Lime juice.

Just a squeeze of lime on top, and that's all we do, but, hey, I live in California, and we have an abundance of different dietary preferences. When I host, I try to have something for everyone. In the book, I actually have two vegetarian samosas, one using lentils, because I love pantry foraging. If it's in the cupboard and I can make a meal out of it, it's a big win. Those lentil samosas use the same spice style as a ground beef, but just using that vegetable in place of the red meat, and a feta and herb samosa, because sometimes you don't want to cook that much, so you just mix together some things, bold and fry.

Kousha Navidar: It really touched me when I was reading this book because I was born in Iran, and so Persian cooking is close to my heart, obviously, and we call them Sambooseh, but lentils are a huge part of the cuisine as well. It was so interesting to see that relationship. Do you see that a lot, as a food writer, all of the kind of the matrix of the world of cuisine, I guess, how all of these ingredients and approaches can be trace back to each other across nations?

Kiano Moju: Of course, I think the way we define cuisine, we think very much like food is very fixed, and it's from a country, but food is literally defined by trade. When you're telling me that, what do you call them in Iran again?

Kousha Navidar: Sambooseh.

Kiano Moju: Sambooseh. I'm going to tell you back. On the coasts of East Africa, they're called Sambusa, because that dish, it's not a coincidence. It's because of those trade routes from East Africa, the southern part of Middle East, all the way to India and back, everything that touches the Indian Ocean. People were sailing, they were trading, and they were exchanging ideas and ingredients and food. I'm very excited for people to find those connections, and just for people to be like, wait, how is this thing on a different part of the globe so similar to mine? The answer is almost always trade.

Kousha Navidar: [laughs]. Yes, spoiler alert. Let's go to Mohammed in Riverdale, New York. Hey, Mohammed, welcome to the show.

Mohammed: Hello. Hi. Thanks for taking my call. Hi. Great show, love anyway, love your station.

Kousha Navidar: Thank you.

Mohammed: I'm from Kenya originally, and one of the things that I miss here the most is the breakfast, which is the Mandazi, and you have it with-- I've forgotten the bean that it is, and it's cooked out in coconut milk. I'm from the coast, so I'm very partial to Swahili food.

Kousha Navidar: Oh, wonderful. Mohammed, thank you so much. Kiano, listening to Mohammed, any sense of what that bean might be? Not to put you on the spot, but are you familiar with that dish?

Kiano Moju: Yes, Mandazi. For those who haven't had it, it's a doughnut that looks pretty similar to a beignet. It's fried dough, very commonly shaped as a triangle in Kenya, and depending on where you are in the country, people are going to spice it up differently.

On the coast, yes, as you said, coconut milk is common and some other spices. I'm wondering if you're thinking of the cardamom pods, which is they look like that. They're like a little green. Then you crush them up and they have these black seeds, which is a version I feature in the book. It's not my grandma's Mandazi, because the coastal ones are better. Anyone who's willing to tell the truth will tell you the coastal Mandazis are the best type.

Kousha Navidar: Mohammed, how does that feel hearing her say the coastal ones are the best?

Mohammed: I agree wholeheartedly, yes.

[laughter]

Kousha Navidar: Mohammed, thanks so much for that call. We really appreciate it. Let's go to Isata in Florence, New Jersey. Isata, hi. Welcome to the show.

Isata: Thank you for having me. I want to give shout out to Kiano for writing about African food. We are looking forward to have more writers that will write about African food. My favorite dish from Africa is the peanut butter soup, and I also love jollof. Our jollof rice is different from the Nigerian jollof rice. I'm from Sierra Leone, so we cook our jollof rice differently.

Kousha Navidar: How do you cook it?

Isata: Thank you, Kiano.

Kousha Navidar: How is the jollof different in Sierra Leone?

Isata: It's the flavor. The way we prepare it, like Kiano said, they use tomato base, and did she say onions? The seasonal spice that we add to our own tomato, onions, and the spice, I think the seasons are different from the Nigerian, so that what makes it different, and it gives it a better flavor and better taste.

Kousha Navidar: Well, Isata, we really appreciate you calling and for giving that shout out. Thank you so much. Let's go to Cal in Elmont, New York. Hi, Cal. Welcome to the show.

Cal: Hi, how are you?

Kousha Navidar: Wonderful, thanks. What do you want to say?

Cal: Good job. Good job, young lady. Good job. I appreciate this my first time getting through, but I'm a good listener, and I want to compliment or to the person, talk more about the moi-moi that makes out of black-eyed beans. You can use it for breakfast. You can use it for lunch. You can use it for dinner. Can you tell the listener about moi-moi from your point of view?

Kousha Navidar: Cal? Thank you so much. Kiano, I see you nodding your head. Moi-moi, do you want to talk a little bit about that?

Kiano Moju: Yes. Moi-moi, it's really hard to describe foods where you don't have an equivalent, but essentially, it's black-eyed peas that have been skinned, soaked, and then they're blended with peppers and onions and seasoned, and typically wrapped in a leaf similar to banana leaf and then steamed. It's like a very deeply savory steamed bean cake, and they can be stuffed with all kinds of things, hard boiled eggs, corned beef, and I don't think I went to a Nigerian house party growing up where moi-moi was not somewhere on the food table.

In the book, I didn't do anything with moi-moi just because that's going to be tier two of level of cook is not for beginners. The presence of black-eyed peas is really big and really important. I just think we skip it a lot, but if you go to your local grocery store, especially if it's big, they're going to be in the canned bean section, right next to the kidney beans and cannellini beans. I use them in the book in my harissa chili. Harissa is a chili paste from North Africa, so it does a lot of the work for you to make a really flavorful chili without cooking it all day.

The black-eyed peas, they're so perfect in there. They're little, so you don't compete against the beef, and they hold up their shape because you don't want your beans turning to mush. If you've never cooked with a black-eyed pea falls upon us, use them in your chili, and you will be shocked that you haven't cooked with them before.

Kousha Navidar: That's wonderful, and Cal, we want to say thanks for giving Kiano a chance to talk about that. Let's go to Leslie in the Bronx. Hey, Leslie. Welcome to the show.

Leslie: Hi. When I was traveling in Accra, Ghana, my favorite dish was barracuda with red red, and I'm curious about what the ingredients in red red was.

Kousha Navidar: Oh, interesting. Leslie, thanks so much. Red red, are you familiar with that, Kiano?

Kiano Moju: I am. I actually traveled to Ghana while I was writing the book. There's actually some Ghana travel photos in there. So beautiful, and the food was delicious, and I had red red a few times. It's a stewed black-eyed peas. I haven't cooked it myself, so I don't know all the ingredients, but from my cook self, I'm always sitting there trying to taste what's in there. I can taste the palm oil. I can taste the tomato. I can taste the chili in there. It's a wonderful black-eyed pea stew from Ghana, and is probably one of my favorite dishes I had on my trip there.

Kousha Navidar: Wow. Leslie, thank you so much for that. Just to talk about the photography, because it's a big part of the book. The book is filled with beautiful images of food. Can you tell us a bit about the photography, and what you were looking to do with this book in terms of the look and the style?

Kiano Moju: Yes, of course. For a lot of people, they haven't seen much about culture within Africa, what it looks like, what people are living, what the markets are like. During the three years I was writing this book, I brought my camera with me, taking photos along the way so people could just see how the markets where these foods are coming from, and the environments people are enjoying them in.

I went to Kenya, Ghana, and Senegal, and it wasn't really with intention of like, oh, I need all these places for the book. These are just places that my life is leading me at the time. Visiting friends, going to weddings, seeing family. It was really exciting to see what we all had in common, because these are countries that aren't necessarily next to each other, and also seeing the different things we carried in our market. Throughout the book, if there's a recipe that is inspired by somewhere or relates to, you'll see a collage of travel photos right after it.

Kousha Navidar: We've got time for just one more caller. Rudolph in Jersey City. Hey, Rudolph. Welcome to the show.

Rudolph: Oh, thank you so much. I really enjoyed the show. Thank you for writing the book. It's very much needed. I just wanted to correct an impression by young lady from Sierra Leone talking about rice, jollof rice. The Nigerian jollof rice is the best in West Africa. I hope they also will agree with me. There's a war going on about that, and we won the war. I want to correct that impression on behalf of 200 million Nigerians, who I'm sure are happy to hear this.

Kousha Navidar: Rudolph, thank you so much. We're not here to take sides, but we appreciate the enthusiasm. It is wonderful to hear people's love for food of all different kinds. So Rudolph, thanks a lot for calling about that, and it makes me think, Kiano, as we wrap, how do you hope people will begin to think about African cuisines and traditions after reading this cookbook?

Kiano Moju: My biggest hope is that people realize that even though a region can be so far away from you physically, like I'm in California, I am so far from Kenya right now, but through cooking and through your kitchen, you really can experience a culture. These recipes, they focus on easy to find ingredients. They give you an introduction to these flavors and flavor combinations. I really just hope people find new favorites that they can fold into their weekly cooking routines.

Kousha Navidar: Absolutely. Kiano Moju is a culinary writer, producer, food writer, and recipe developer. Her new cookbook is titled AfriCali: Recipes from My Jikoni. Kiano, thank you so much for letting us into your Jikoni for a little bit, into your kitchen. We really appreciate it.

Kiano Moju: Oh, thank you. Asante Sana.

[music]

Kousha Navidar: A new book from award-winning writer Fiona McFarlane, examines the effects of a fictional serial killer and his crimes on those touched both directly and indirectly. She joins us next to discuss Highway 13. It's a collection of short stories. Stay with us.

Copyright © 2024 New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.

New York Public Radio transcripts are created on a rush deadline, often by contractors. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of New York Public Radio’s programming is the audio record.