Journalist Barbara Demick Follows A Case Of Twin Separation in 'Daughters of the Bamboo Grove'

Alison Stewart: This is All Of It. I'm Alison Stewart, live from the WNYC studio in Soho. Thank you for spending part of your day with us. What day is it? It's August 7th, not July 31st, which you heard our Billboard. Let's tell you what's going to be on the show today. We're going to talk to two solo show performers at the Soho Playhouse. They both have shows running now. Bill Posley discusses The Day I Accidentally Went to War. He'll reflect on his experience enlisting in the military, being deployed, and coming home. Then Morgan Bassichis, his play is called Can I Be Frank? It interprets the life and work of gay comedian Frank Maya. Then later this hour, we'll have some fall travel tips from NerdWallet's podcast host, Sally French, and she'll take your calls. That's the plan. By the way, I have an AC head cold, so I'll do my best. Let's get started with the story of international adoption.

In 1992, China officially opened its doors to international adoptions. Many of those adopted children ended up right here in New York City. The New York Times Magazine even ran a cover story about it in 1993. American parents were told that these babies were unwanted girls, a result of China's one-child policy. Often, Chinese families might abandon their daughters in favor of trying for a son.

One of those adopted American parents was told that her daughter, Esther, once called Fangfang, was one of these discarded girls. Journalist Barbara Demick soon uncovered that Esther was abducted from her family. Esther was taken as a toddler by the Chinese State Family Planning Commission, brought to an orphanage, and event adopted. Her parents, two older siblings, and a twin sister remained in China.

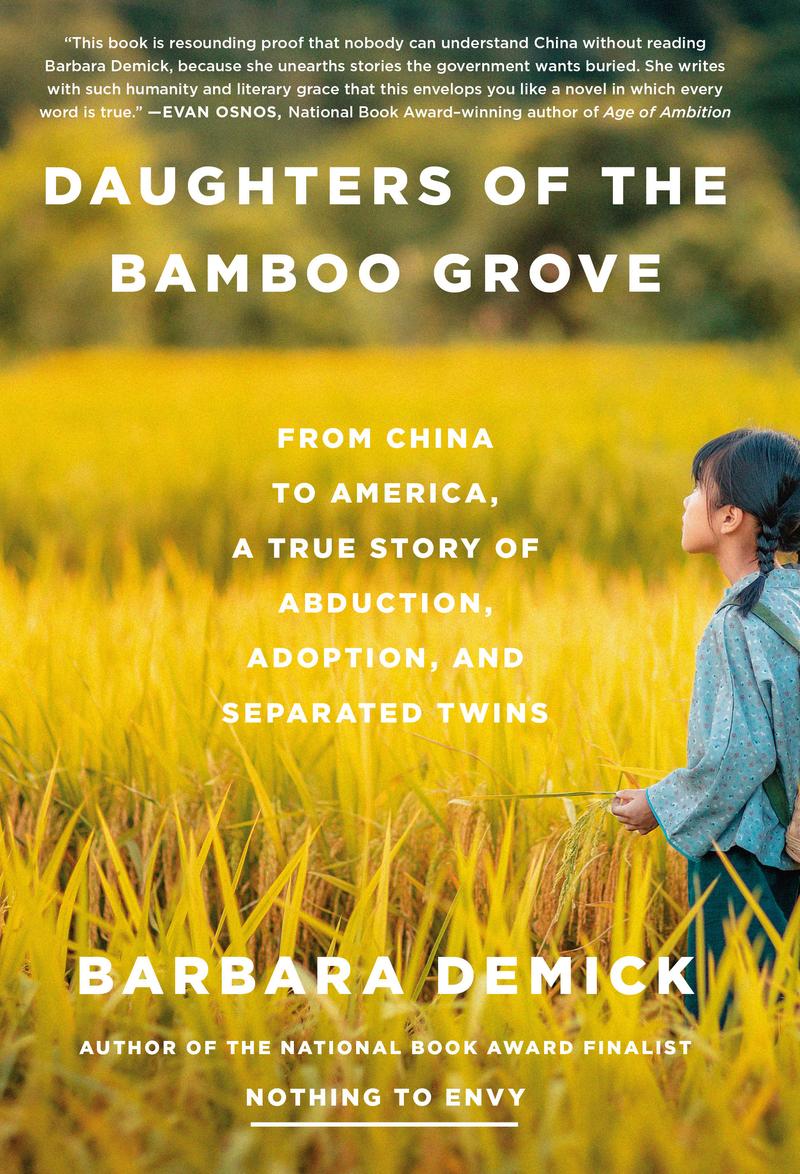

Barbara's reporting reveals that Esther is far from the only adopted child who was forcibly removed from her birth family. Barbara Demick tells the story of Esther, her birth family, and the underside of adoption from China in her new book. It is titled Daughters of the Bamboo Grove: From China to America, a True Story of Abduction, Adoption, and Separated Twins. It is out now, and Barbara Demick joins me in studio. It is really nice to meet you.

Barbara Demick: Thanks so much. I'm really happy to be here. One of my favorite shows.

Alison Stewart: Thank you. Listeners, we want to hear from you. Have you adopted a child from China? What were you told about their background? Or maybe you were someone who was adopted from China. What do you want people to know about your birth family? If anything, what did you know about your birth family? We are discussing Chinese adoptions in America and the one-child policy. Our phone number is 212-433-9692 212-433-WNYC. I want to back up, and I want to explain this for everybody what the one-child policy is. Why did the government in China decide that a one-child policy would be a good strategy for the country?

Barbara Demick: This was an idea that started in the '60s. You remember there was a book, maybe you're too young, The Population Bomb. It was millions of people are going to starve to death. As a friend of mine who's written about this has said, this was like bell-bottoms and sideburns. This was a craze. Too many people. Various governments, like in India, they had tried to limit births and forcible vasectomies. China was the perfect laboratory because they were in a rush to get rich fast. There was no religious precepts against abortion or birth control, and it was a totalitarian regime, so they had this very, very strict policy.

People who didn't follow the rules could have their houses torn down, their property taken away, their animals confiscated, and then they started confiscating babies. This was because of international adoption, which was very lucrative.

Alison Stewart: The family that you follow is deep in the countryside, where you might not think the government would be as strong or would reach as far, but that wasn't true when it came to the one-child policy. Why not?

Barbara Demick: The government was everywhere. There were Chinese Communist Party monitors in every village. The people in the countryside they were powerless, without voices, without any political clout. Not that you would have political clout in a country like this, and they were vulnerable. These family planning officials would sneak into very, very remote villages, and they would look for baby clothes on clotheslines or they would talk to nosy neighbors.

The villages where these children were taken were all very remote. One of them, we had to hike up a goat path. The one where the twins came from, we had to walk along a little log bridge, and there's a picture of it in the book, but they were very remote and very vulnerable.

Alison Stewart: The Zeng family that you write about, what do they think of the one-child policy?

Barbara Demick: This is a funny thing. They're very loyal, patriotic Chinese. They really love the Chinese Communist Party. They feel like it lifted them out of poverty. They respected the one-child policy. They believed in the policy. That didn't mean that they were actually going to follow the policy. I think it's like us. I believe in taxes. I'm not really happy about paying them. I do. The typical young rural couple, they had had two daughters very early in their pregnancy. They had already been punished for having the second daughter.

The paternal grandfather was really pushing them to try for a son. This is the son carries on the family name and conducts rituals at the cemetery, blah, blah, blah. They pushed them and pushed them and pushed them, and the young mom at the time hid out actually in a bamboo grove. That's where this comes from, to give birth secretly so nobody would see she was pregnant. Pregnant women were often picked up and forcibly aborted up to eight, nine months. Very brutal, unsanitary conditions. She went to have her long-awaited son, and boom, two more daughters.

Alison Stewart: Twins.

Barbara Demick: Twins. They said she wasn't looking like she felt so well. They were like, "Something's wrong with this pregnancy," and it turns out to be twins.

Alison Stewart: She gave birth to one, and then she's like, "Something is still moving inside."

Barbara Demick: You would have thought they'd be horrified, but the father, who's really an unusual rural Chinese man, loved girls.

Alison Stewart: He could have been a stay-at-home dad.

Barbara Demick: You're right. If he lived in Scandinavia, he probably would have been, I'll stay at home and take care of-- He loved girls. He is very gentle, soft spoken, doesn't smoke. They really wanted to keep the girls, and she was actually pleased. It was a little bit of a comeuppance to his patriarchal father. They tried to hide the girls in this awkward ruse. They left one with an aunt and uncle, and that's when these family planning officials actually came in, immobilized the aunt. There were 10 people who broke into the house, and they took the baby.

Alison Stewart: How did you first get involved with the Zeng family

Barbara Demick: I was a reporter in China from 2007 to 2014, which was actually a relatively open period for journalists. I was traipsing through rural China writing this story. I'm not an adoptive parent myself, but I had a lot of friends who adopted. Usually, women like myself who were professionals didn't get pregnant early in life. They were building their careers. I was very interested in this, and I had heard these rumors that babies were being snatched. I had heard from various Chinese journalists about this village. Chinese journalists were way ahead of me, but they weren't able to report-

Alison Stewart: Oh, interesting.

Barbara Demick: -because of censorship. I heard about this family. I crossed the little river bridge and I interviewed the mom and the remaining nine-year-old girl. They told me the whole story about how they had twins and one was taken, and the little nine-year-old girl who was adorable, said, "I miss my twin sister. I want to play with her, blah, blah, blah, blah." I made a video, and when I was leaving, the mom said, "Thanks for visiting, come back and bring our daughter."

Alison Stewart: Oh.

Barbara Demick: Anyway.

Alison Stewart: Wait a minute. What did that do to you emotionally when she said that to you? I know you're there as a journalist, but when someone says that to you--

Barbara Demick: I didn't think that was possible. I was like, "Yes, thanks. I'll try." Anyway, I got back to my office in Beijing, and I have to admit something here. I was procrastinating, just messing around on the computer. Things were much more open on social media at that time. This was 2009. I found these different forums on Yahoo, actually, for parents who had adopted. They always posted pictures of their kids dancing the Nutcracker, riding ponies, enjoying American life.

They were very proud of these ridiculously adorable kids. One family I found seemed to have adopted around the same time, the same area. This girl was taken when she was almost two, so she was older than other adoptees, and I knew what she looked like because I had met her identical twin sister. It's complicated what happened next, but I started trying to find the family, and they completely freaked out. They cut me off through an intermediary, said, "We can't deal with this."

They were evangelical Christians in Texas. They had, in fact, started a little NGO because there was a big movement among evangelicals. Adopt the world, save the babies. That was it. I really couldn't write anything. I couldn't out a nine-year-old as being a stolen child. I sent what I had to the family in Texas, I contacted the family in China and said, "Look, your daughter is safe. She's been adopted. I just don't think you can contact her now." They were actually understanding. They were happy she was alive, and then that was it till 2017. Should I just keep going?

Alison Stewart: Let's stop there because I do have a couple of questions for you. This actually came through via text. Can you explain why these adoption schemes were so lucrative? Who pocketed the money?

Barbara Demick: This is actually a very important question. Thank you, listener. Most of the adoption fees went through Beijing and adoption agencies in the US. I have not found any corruption there, but there was a rule that adoptive parents had to donate to the orphanage that fostered the child $3,000 cash, clean hundred-dollar bills, and they had to carry it with them to China. Parents picked up their kids in China. This was a fortune in rural China.

These orphanages were government-run. They were part of larger social welfare institutes. I've got to say something that maybe exonerates some of the Chinese here. These orphanages were not very well funded by the government, and this $3,000 sometimes it went to people's pockets, but sometimes it was just running the orphanage.

Alison Stewart: My guest is author and journalist Barbara Demick. We're discussing her new book, Daughters of the Bamboo Grove: From China to America, a True Story of Abduction, Adoption, and Separated Twins. Listeners, we'd like to hear your story. Have you adopted a child from China? What were you told about their background? Or maybe you or someone you know was adopted from China? We'd like to hear your story as well. Our number is 212-433-9692 212-433-WNYC. Once a child is abducted, do the parents have any recourse on getting the child back?

Barbara Demick: No. These people are not connected. They have no money. They are often illiterate or semi-literate. Often, family planning officials, family planning as in a euphemism for the enforcement agency, would ask for mone,y but they were ridiculous sums that the family couldn't afford. These were very poor people.

Alison Stewart: They couldn't take the child, but they could take the child. It wasn't legal.

Barbara Demick: It wasn't legal, but it was a don't ask, don't tell. They needed the money. How it was split between the family planning in the orphanage, I don't know. They had to place ads in newspapers saying we found a baby so and so, but most of that information was fabricated. These people were rural villagers. They didn't read these newspapers. Some of them were legal newspapers, and they generally moved them on about six months later.

Alison Stewart: I want to ask about the preference for boys. What are some of the cultural and economic explanations for why Chinese family might place such emphasis on having a boy?

Barbara Demick: I think the main one has to do with retirement. The tradition is that the boys take care of the parents in their old age and that the girls marry out. It had been a very common cultural thing. The girl goes to another village, marries, and takes care of her in-laws, so they were like spilled water. Something that's really very important to say here, this was changing since there's adoptive parents, no doubt listening, and adoptees.

During the '80s and '90s, there really were a lot of abandoned babies, but by about 2000, there's not an exact cutoff, Chinese were getting a lot richer, and the attitudes towards girls were changing. The girls were starting to work in the factories in southern China, they were making money, they were sending the money back to their parents, and people didn't want to give up their daughters. There was just such a change in China over that decade, and that's when these babies got abducted. The earlier adoptions, I think really were abandoned.

Alison Stewart: What messages were American adoptive parents given about the children?

Barbara Demick: A very convenient lie is you're rescuing a baby from the trash keep of China, and it was very comforting to the adoptive parents. I think it was a very destructive narrative for the adoptees, many of whom still have deep psychological issues about abandonment. Something else, sorry, I'm talking like a broken record here. I'm saying abandonment, but it's really relinquishment because some kids were taken violently like this twin, but some were given up under great duress, and there was just a continuum of duress. I think very few of those girls would have been relinquished if not for the one-child policy.

Alison Stewart: Esther's adopted mom is from Texas. What did she tell you about why she decided to adopt and why she decided to adopt from China?

Barbara Demick: Esther's mother, who was a wonderful person as I've come to know, wanted to be a missionary as a child. She was very motivated by humanitarian concerns, and she was older. She already had an adult son. Her husband had adult children from a previous marriage. She heard a program about babies being thrown out. One in particular about a girl who was thrown down a well because her family wanted a boy. She's soft-hearted, and so she decided to save the babies.

Alison Stewart: Was altruistic on her part.

Barbara Demick: It was altruistic, and it was an extension of her desire to be a missionary. She adopted two girls from China, one a little bit older, and then Fangfang, who became Esther.

Alison Stewart: Esther had a little bit of a harder time melding into the family a little bit.

Barbara Demick: That's right, because she was almost two when she was taken. She was two and a half when she was adopted, and she could already speak very coherently and walk, and she was a very precocious kid. Marcia's husband, who has unfortunately since passed away, said it almost seems like she had another family.

Alison Stewart: It's interesting because Esther's Chinese family, as you described, they grew up in rural poverty. They're doing better now, but she grew up middle-class in America.

Barbara Demick: Struggling middle class.

Alison Stewart: Struggling middle class.

Barbara Demick: I think this very typical American story of people who were falling out of the middle class. Her husband got cancer. He had to leave his job. She was taking care of young kids. She retired early. It was just typical. Not quite enough health insurance, not quite enough pension.

Alison Stewart: Gosh, that's interesting. I think about that for a minute. As you said, when she turned 17, things changed. She was able to meet with her twin. That must have been an incredibly hard decision for her to make.

Barbara Demick: It was. At first, she found out about this whole thing when she was nine years old, and she was horrified. "I have to go back to China." As she became a teenager, she saw that she looked different from other people. She grew up in a very, very white community in rural Texas, and she started following Chinese fashion bloggers. At that point, that's when somebody in her family contacted me and said, "Can you help?"

Alison Stewart: How did you feel about being contacted? "Can you help?"

Barbara Demick: It was really out of the blue. This was 2017.

Alison Stewart: Wow.

Barbara Demick: It was right after Trump's inauguration. It was full of protests in New York and at the airports. It was a crazy time, but I was like, "Wow." I never forgot this story. I didn't think I'd write about it, but, of course, I couldn't not help. As I got sucked into it, I shouldn't say sucked into it, because I put myself into it, I realized how much trauma I had caused the family in a way, and I felt obliged to help.

Alison Stewart: Did you feel like you caused the trauma?

Barbara Demick: I did.

Alison Stewart: Why?

Barbara Demick: I felt like I was writing these stories as a journalist and that I had not thought enough about the psychological implications. I was trying to help the Chinese family. I wasn't even trying to write a story at that point. I was just trying to see if I could find her. I like to fool around on the internet, and I don't know, I just got more and more involved. I found Shuangjie. I started sending letters between them. Then it was text messages. I set up a video chat, and finally, we all went to China together.

Alison Stewart: How are you feeling about it now in 2025?

Barbara Demick: I feel very good about it. It's not a fairy tale. I think people want to look at this as oh, separated, transunited. It's a fairy tale. There's tensions there and issues. We had really hoped that Shuangjie could come to the US the following year, and then that was Covid 2020. We've talked about it, but it's very difficult for a Chinese person that age to get a visa to the U.S. Because of the political situation, she doesn't have a passport. The twins have found it hard to keep up the intimacy because they don't speak the same language. They're texting, and for all the wonders of technology and the AI interpreters, it's difficult.

Alison Stewart: That's interesting. What would you say to someone who has the ability to introduce an adopted child to original family members, knowing what you know now?

Barbara Demick: I've been asked this a lot. The main thing I would say is it's definitely up to the child. They have to decide. I don't think there's a right or a wrong answer, but I just wrote a piece about this for the New Yorker that ran a few months ago. There's a lot of adoptees, and a lot of Chinese families are finding each other through DNA testing.

Alison Stewart: Oh, gosh, yes.

Barbara Demick: Some adoptees are looking and desperate to find their birth parents, and others are just like, "Forget it. I'm happy with who I am." I can't say who's right and who's wrong, but it's really up to them.

Alison Stewart: We should point out, though, that the one-child policy has been phased out in China. Why was that?

Barbara Demick: They were running out of people. What was surprising about this was not so much that they executed the policy, but that it dragged on till 2015, when demographers were warning this is a disaster. You have all these bachelors who can't find wives. You don't have the low-cost factory workers who were responsible for the Chinese economic miracle, and so now China's population is shrinking.

India is now the world's most populous country, and China is expected to lose half their population by the end of the century. It's really shrinking. The Chinese government just made this 180-degree turn where they're offering incentives for people to have more babies. The same people who would beat pregnant women and drug them for forced abortions are now offering them rice cookers and water bottles, and sometimes money to have more babies.

Alison Stewart: The name of the book is Daughters of the Bamboo Grove: From China to America, a True Story of Abduction, Adoption, and Separated Twins. It's by Barbara Demick. Barbara, thank you for joining us in studio.

Barbara Demick: Thanks so much.