John Lewis Speaks at the March on Washington (Full Bio) (Day Two)

( National Archives )

Title: John Lewis Speaks at the March on Washington (Full Bio) (Day Two) [MUSIC - Luscious Jackson: Citysong]

Alison Stewart: This is All Of It on WNYC. I'm Alison Stewart. Full Bio is our book series where we spend a few days with the author of a deeply researched biography to get a fuller understanding of the subject. John Lewis: A Life by David Greenberg takes on an icon of the civil rights movement. Yesterday we heard about Lewis's upbringing in Alabama and his young adulthood in Nashville, where he was instrumental in the Student Movement. Today we'll look at his role in the Freedom Rides and his role as the chair of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, SNCC.

This is David Greenberg, author of John Lewis: A Life.

[music]

David Greenberg: We're going to look at 1961 and the Freedom Riders. They were following up on the 1960 Boynton v. Virginia, which basically said there shouldn't be segregation in interstate bus terminals. You write that Lewis needed no persuading to become a Freedom Rider. We tend to think of John Lewis as a civil rights leader, but at this moment in his life, where is he?

David Greenberg: He's still a college student. This is 1961, he's 21 years old. They're sort of fresh off this victory from 1960 with the sit-ins, although there's a lot more work to be done in Nashville even after that first year. My book actually gives a much more detailed account than we've had in other civil rights histories of the years of '61, '62, '63, where Lewis is fighting in Nashville.

He learns of a project sponsored by a group called CORE, the Congress of Racial Equality, that is going to have Black and white teams of riders go from Washington, DC all the way through the Upper South, the Deep South, winding up in New Orleans to test the Supreme Court ruling that says you cannot segregate not only the buses, but also the bus terminals and the dinettes at the bus stations and so on, which were routinely being violated across the South.

I think it's Metz Rollins, who's one of the ministers in the Nashville group, he just knows John Lewis would be perfect for this. That this would be his kind of project. Even though he needs to cut out of his school semester and maybe wind up missing graduation, he decides that this is something he wants to do.

John Lewis is a member of that original Freedom Rides leg. Then he actually leaves the trip for a couple of days because he's under consideration for a fellowship to study abroad, much as Jim Lawson had, either in India or-- he really wants to go to Tanzania. While he's away, one of the buses is firebombed by a group of Klansmen and white vigilantes in Anniston, Alabama, and then the other bus is met with violence when it arrives in Birmingham. The violence is so bad, so horrific, that the leaders of the Freedom Ride decide they're going to abandon the project.

At this point Lewis has returned to Nashville for a moment. He's with all his old friends. It's these students, 21-year-old, 20-year-old, who decide, no, no, the show must go on. They, the Nashville Movement, revive the Freedom Rides, get people together to continue them, and carry it through to completion.

Alison Stewart: Those who participated in the Freedom Rides, they wrote wills and letters to their families. They were really headed into danger. What was the level of danger for these young adults?

David Greenberg: Well, look. Especially after that Anniston bus bombing, where someone threw a Molotov cocktail onto the bus and the whole thing erupted in flames, after that they knew that their lives were very much on the line. John Lewis had been beat up once already in Rock Hill, South Carolina.

Alison Stewart: Can I stop you there? Can you describe the scene in South Carolina where he was beaten up?

David Greenberg: Yes. That was actually one of the lesser ones, but it is served early on in the Freedom Rides. Go into the bus station is their plan. He goes into the white area, the white waiting room area, the white restroom area, and there's a few young thugs there. One of them is a man named Elwin Wilson, who's a member of the Klan. They probably all are Klan members. A lot of young guys would just join the Klan like that. Lewis gets slugged in the mouth, falls to his knees, he's bleeding. Then his white seatmate, a somewhat older man named Albert Bigelow who was a peace activist and former hockey player at Harvard, he steps up. They start pounding on him too.

A young woman then steps up. They hit her, and at that point, the police finally put a stop to it. John Lewis says, "No, no, we don't want to press charges because these people too are a victim of a corrupt segregationist system." They go on their way, Lewis with his bloody mouth. Years later - I'll just digress to tell the story - the same man, Elwin Wilson, just after the inauguration of Barack Obama, is feeling this remorse over how he treated these people, and he realizes the wrong. He realizes the evil of his former beliefs.

Anyway, through an intermediary at the local paper, he gets in contact with Lewis's office. They're on Good Morning America, where he apologizes. He cries. Lewis forgives him.

Elwin Wilson: "I'm sorry for what happened down there."

John Lewis: "Well, it's okay. It's all right. It's almost 48 years ago."

Elwin Wilson: "That's right."

John Lewis: "Yes. Still remember that day, Will?"

Elwin Wilson: "I try to get it out of my mind."

Commentator: "Did you ever imagine this moment?"

John Lewis: "I never thought that this would happen. It says something about the power of love, the power of grace, and the power of people to be able to say I'm sorry.

David Greenberg: In a way, it does show Lewis is right about nonviolence. That you can change people's hearts. Maybe it takes 47 years, but it can work. Lewis is quite ready to endure this violence. I found this remarkable press conference. I think it's his first national press conference, where he's there with Martin Luther King and James Farmer and some of these other titans of the movement.

John Lewis was asked about the violence he's going to confront. He says very frankly, "Look, I don't want to die. It's not like I'm going into this wanting to die, but I'm ready to die because I believe in this cause of human equality and freedom." It's an incredibly mature and courageous thing for a young man to be saying with such kind of equanimity. Then, of course, he does go on to endure even worse violence. Once the Freedom Rides are revived in Montgomery, in particular, the local police basically get out of town. They hide out while a mob is awaiting the Freedom Riders.

When they arrive in the Montgomery bus station, there's a full-on riot. Lewis is smashed over the head with a Coca-Cola crate. Another friend of his, William Barbee, is beaten so badly he had permanent brain damage. This is not just getting smacked around. He nearly lost his life then as he nearly lost it again in later years. It took an immense amount of courage and dedication to the cause to know you could face that kind of violence and even death and go forward with it anyway.

Alison Stewart: My guest is David Greenberg. We're talking about his book, John Lewis: A Life. It's our choice for Full Bio. I want to finish up with the Freedom Riders by talking about the Kennedy administration who was not on board. How did the Kennedy administration help or hinder the Ride and when did they truly get involved?

David Greenberg: Well, the Kennedys initially-- and of course, John F. Kennedy is president, his brother Robert F. Kennedy is the Attorney General. By and large, they are trying to, in small and modest ways, advance the cause of desegregation and equality, but it's a politically tough time because the Democratic Party at this point is still very much dependent on the South, which votes Democratic. They need these Southerners as part of their coalition. They're moving quite slowly. When the Freedom Rides begin, they tell the Justice Department that, "Okay, we'll keep an eye on things." They're nominally supportive.

After that Anniston bus bombing and after that horrific violence, the Kennedys say, "Look, we need a cooling-off period." It's not that they're siding with the segregationists. They just see, is this a provocation? Do you really need to go in and stir up trouble? Can't we find a behind-the-scenes way to try to get these goals achieved? Of course, John Lewis and his fellow activists believe that unless they're out there in what they call direct action, then the Justice Department will go slow, they'll back off. They won't feel the urgency. There is this conflict where they see Bobby Kennedy at this point as someone who's telling them we need a cooling off period.

They think, no, just the opposite. We need to turn up the heat and really get this issue taken care of. By the end, of course, the Justice Department does send people down to help them out. In fact, one of Bobby Kennedy's aides is himself beaten with a lead pipe and thrown under a parked car during the Montgomery riot that I just described. Eventually, under pressure, the Justice Department leans on the Interstate Commerce Commission, I think it is, to fundamentally revise its rules so that this Boynton decision that you mentioned will be upheld, and that there can be no more segregation. In that sense the Freedom Rides are very successful, and the Justice Department comes round to advocate their cause.

Alison Stewart: There's a whole bunch of detail in your book, which I'll let people read about when they pick it up. I want to move on to 1963 and the March on Washington. By now, John Lewis is the chairman of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, SNCC. What was the purpose of SNCC?

David Greenberg: SNCC was formed in 1960 as those sit-ins were really getting going. There was a recognition that we had all these different student groups in different parts of the South, and that it would be useful for them to have some kind of, well, coordinating committee. It really started as just a simple vehicle for these different student leaders and ministers to be in touch with one another. Soon, like any organization, its leaders decide that they should set some bigger goals and ambitions of their own. Of course, some of the students soon graduate, so they're no longer students. They're now young civil rights activists.

SNCC really has a variety of causes. Some of it is to continue these campaigns of direct-action desegregation in various cities and towns. They also take up what we might call community organizing, but really in rural areas in South Georgia, in Mississippi, getting local African Americans who, like the Lewis family, have been somewhat cowed into submission to recognize that they can try to take their fate into their own hands. In other words, the activism doesn't have to be limited to the students, many of whom might be called middle class, but that these poor farmers, day laborers, domestics, women who work as domestics, they too can be part of this.

SNCC is really trying to organize voter registration efforts and other efforts in a variety of cities and states around the South.

Alison Stewart: John Lewis is the chairman of SNCC. It's the March on Washington. He's going to give a speech, but it was a little bit controversial. What was the controversy about, and to you, as someone who's researched it, what stood out to you about his speech?

David Greenberg: It's a wonderful story, and I can't do justice to the whole saga here. People will have to read it, as I hope they will.

Alison Stewart: Yes.

David Greenberg: In a nutshell, the March on Washington was originally conceived by two great civil rights leaders: A. Philip Randolph, a longtime labor leader, and Bayard Rustin, who was his chief lieutenant. When they conceived the march, they were really thinking it should be for economic causes, for jobs, for economic opportunity. Once Martin Luther King comes aboard and they really put together a coalition of all the leading civil rights groups, including SNCC, it becomes for freedom too. You think of the jobs as Philip Randolph and the freedom as Martin Luther King.

The other thing that happens is between the time the march is first conceived and the time that John Lewis comes on board, the Kennedy administration introduces its civil rights bill that would go on to be the famous 1964 Civil Rights Act. Instead of being a march to prod the Kennedy administration to action, the Kennedys figured out they should get with the program. I wouldn't say they're trying to co-opt the march, but they do turn it into a rally to get this bill passed. SNCC, as the most radical or militant of the many partners in the march, they're not so excited about Kennedy's bill. They see a lot of ways in which it falls short. It's not great on voting.

They're going to need another act later, the Voting Rights Act. It's not great on some issues of police brutality. Some of those issues don't get passed until the Clinton administration puts in important provisions against police brutality. There's a lot of things that are left out. Lewis's speech, which he drafts first himself, but then with input from a lot of other people at SNCC, is a pretty stinging, critical speech about all the things left out of the bill and all the problems. It's not a love letter to the Kennedys or the Democratic Party.

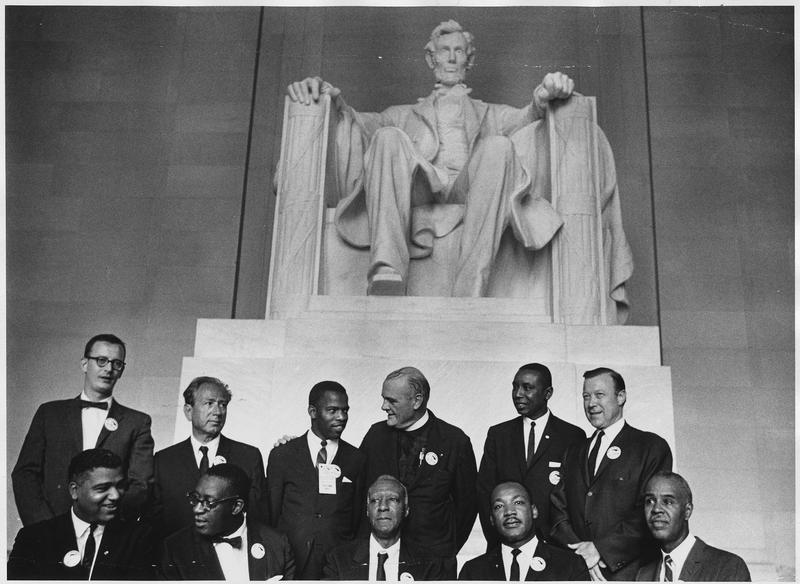

When the advanced text of the speech makes its way into the hands of some of the partners, including, most important, the archbishops - the Catholic Church was participating and the archbishop of Washington was going to give the benediction - he finds objections, says he won't go on stage if this speech is to be given. People at the Justice Department are objecting. Roy Wilkins of the NAACP has objections. In this amazing scene, they're there at the Lincoln Memorial in the shadow of the colossal Lincoln statue negotiating over language changes, making edits and revisions.

Poor young John Lewis, he's done a lot of public speaking in some sense in the movement, but he's never done a big speech before 250,000 people. He had practiced the old version, so he really knew it, and now it's getting revised on the spot. His one source who was there and remembers it said, "I just remember John Lewis saying to everyone, 'Don't change too much. Don't change too much.'" In the end, I think the compromise version of the speech he gave was a masterpiece of political compromise.

He took out just enough to make Martin Luther King and A. Philip Randolph and the others happy that it wouldn't be a sour note in what was shaping up otherwise as a beautiful, historic day of triumph, but he also did not water it down so much that his message was lost. Sure enough, a lot of the next day stories wrote more about Lewis's speech than about Martin Luther King's famous "I have a Dream" speech because Lewis was the one who was still hitting these notes of how much more we still have to do. In a way, you see the early political skills of John Lewis navigating these different constituencies, finding a way to remain principled, even as he also knows how to be a team player.

Alison Stewart: Let's listen to a little bit of John Lewis at the March on Washington.

John Lewis: "We do not want to go to jail, but we will go to jail if this is the prize we must pay for love, brotherhood, and true peace. I appeal to all of you to get in this great revolution that is sweeping this nation. Get in and stay in the streets of every city, every village and hamlet of this nation until true freedom come, until the revolution of 1776 is complete. We must get in this revolution and complete the revolution. For in the Delta of Mississippi, in Southwest Georgia, in the Black Belt of Alabama, in Harlem, in Chicago, Detroit, Philadelphia, and all over this nation, the Black mass is on the march for jobs and freedom."

Alison Stewart: That speech comes courtesy of the WNYC archives. After the break, we'll hear the story of the Selma march. This is All Of It.

[MUSIC - Luscious Jackson: Citysong]

Alison Stewart: This is All Of It on WNYC. I'm Alison Stewart. You are listening to Full Bio. Our guest is David Greenberg, who wrote John Lewis: A life. The 500-page book goes into so much detail that it would be impossible to share it all with you, so we're going by chronology and picked out a few important stories. No story of John Lewis can be told without the Selma march to Montgomery in 1965, referred to as Bloody Sunday. Behind the scenes there was tension between the young leaders of the civil rights movement, James Forman, James Farmer, and specifically Stokely Carmichael, who wanted less civil and more rights. Here's David Greenberg, author of John Lewis: A Life.

[music]

Alison Stewart: I wanted to get into a bigger picture issue with John Lewis. That he really believed there was a Southern Black person experience and a Northern Black person experience, and that they really shouldn't be considered the same thing. Can you explain the Southern Black person experience and the Northern Black person experience as John Lewis might have described it?

David Greenberg: Yes. I think there were a lot of differences as he understood it. He was drawn to, both in Nashville, but then throughout his years in the South, a vision that started with the church, started with people like Martin Luther King, was initially focused on segregation. Because the segregation in the South was not just a matter of separate water fountains and not being able to use the library - that was bad enough - but was really an order where whites were on top, Blacks were on the bottom, and this strict separation was ruthlessly and often violently maintained.

He went to Buffalo as a young boy with an uncle who drove him up there for the summer. They had cousins, uncle and aunt there. Lewis saw in Buffalo a completely different world. It's not to say the North was free by any stretch of racism or discrimination, but whites and blacks lived next door to each other. They rode the bus together. They often interacted with perfect civility and decency. He just saw it was a different way of living. There were many Northerners who would come down and get involved in the civil rights movement.

They tended to have different priorities, just a different way of looking at the world. They were not always as churchy as they like to say. Often came from a more secular-- you might say Marxist or just left-wing radical tradition that was all an analysis of power. We have this today in the academy. Sometimes it can be quite oversimplified that everything's just about power. I think Lewis thought some of the Northerners didn't fully get the experience of growing up in the South, of living in the South under this oppressive regime. There were tensions, really from the beginning, within SNCC and in other parts of the movement.

In those early years, say from '60 to '65 or so, both Lewis and a man named James Forman, who's the executive director of SNCC, I think do a remarkable job of containing those tensions. Channeling them fruitfully. Making sure they don't disrupt the mission of the group. After the passage of the '64 Civil Rights Act, and then the passage of the 1965 Voting Rights Act, there's a question, what should our next big goals be? At that point, some of these differences between the Northerners and the Southerners really start to divide the movement, to the point where within a few years, a couple of years, SNCC is a shadow of its former self.

John Lewis, Robert Moses, Julian Bond, many of its great leaders, leave the organization and it goes in a radically different direction. It's a serious rift, and it's one that I think most people in the movement saw and experienced to some degree or other, although they would to this day probably debate and argue about its particular significance and the merits of one position versus another.

Alison Stewart: March 7th through the 25th, 1965 was the Selma march. What was the purpose of the Selma march?

David Greenberg: In Selma, this was after the passage of the '64 Civil Rights Act, which, as I mentioned, did not do as much as many people had hoped to make voting and voting rights a reality for Blacks in the South. As I think listeners probably know, even though the constitution was supposed to guarantee the vote for people regardless of race, that was not the reality in the South, where all kinds of methods, poll taxes, literacy tests, and often just raw assertion of power prevented Blacks not only from voting, but even from registering in the first place.

The people of Selma had been organizing for some time. SNCC had been there as early as 1963. In late 1964, feeling frustrated with the lack of progress, they asked Martin Luther King and his group, the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, to come in to help out. That maybe King, with all of his media attention, he had just won the Nobel Peace Prize, this could draw attention to Selma and this drive for voting rights. Some of these splits that we've been talking about now start to rear their head, in particular splits between SNCC and SCLC, King's group.

Initially, SNCC was almost like a youth auxiliary to King's group. Its first offices were in a corner of SCLC's offices. King was there at the founding meeting. Again, it's sometimes a North-South distinction. Some of the SNCC members begin to develop a certain amount of scorn, you might even say, for Martin Luther King.

Alison Stewart: Generational differences even.

David Greenberg: Generational differences. One woman I talked to just a couple of years ago while interviewing for this book, it was as if it was yesterday. She said, "I could not believe King was such a conniver and a manipulator." I never heard anyone talk about Martin Luther King that way. This is someone, you might say, from the left, who felt he was not strong enough on civil rights issues. These conflicts emerge, and at one point, some of John Lewis's old friends from Nashville - Bernard Lafayette, James Bevel, Diane Nash - they're all working for King now, interestingly, and they decide "We need to have a march." A march from Selma to the state capital of Montgomery, 50-something miles, I think.

It was the kind of classic tactic that could galvanize attention. Lewis compared it to Gandhi's famous march to the sea. The problem is SNCC really doesn't want to participate because they're kind of feuding with King and SCLC, and they think this is one of his vanity projects. Lewis, who had met King at a young age and always remained loyal to him, would never say a bad word about King. Lewis wants to March. He convinces SNCC to say, "Okay. Whoever in SNCC wants to march as an individual can march. I won't be representing the group." He and a number of others decide to participate.

On March 7th, the day of the planned march, he's at the forefront of the line along with Hosea Williams, who's representing SCLS. They begin to cross the Edmund Pettus Bridge, which is what leads out of town and will take them on the road to Montgomery. There they're confronted by a sea of the local sheriff and his posse, and also state troopers of George Wallace's Alabama National Guard.

Alison Stewart: I think we've seen the footage of this. This terrible beating that John Lewis takes. How far did they think the protests were going to get? Did they really believe they were going to be able to continue on?

David Greenberg: Some people that day brought backpacks and toothbrushes. Others came for a day-long march. People were dressed and ready for different expectations. Certainly the hope was that they were going to march on to Montgomery. That plan is cruelly and brutally interrupted by this police violence that sends John Lewis and other people like Amelia Boynton and others to the hospital. I should say a photo researcher I worked with found this rare footage - I don't know anyone who'd seen it before - of Lewis in his hospital bed that afternoon talking to reporters. What's he talking about? Nonviolence.

Alison Stewart: Wow.

David Greenberg: It's the most amazing thing.

John Lewis: "But I will never forget that day as we crossed the Edmund Pettus Bridge, crossing the Alabama River, and seeing the sea of blue below. The hundreds of state police officers, the state troopers. Sheriff Clark, Jim Clark, the sheriff of Selma, and members of his posse with billet clubs and bullwhips, and chasing us with horses and tramping us and releasing the tear gas. I almost died. I think on that Sunday afternoon I saw death when I was being beaten."

David Greenberg: This of course has the effect of once again outraging the nation. Footage of the beating is shown on television that night. Photographs run on the front pages everywhere. The next day, Lyndon Johnson is moved to action to finally introduce that voting rights bill, which he wanted to introduce. There's a film about Selma that got that wrong, a Hollywood feature film, several years ago. Johnson favored the voting rights bill. He just wasn't ready to introduce it yet because it was so soon after the '64 bill, but now he realized he had to move. The time had come.

In that sense, John Lewis's beating and heroism led fairly directly to the passage of the 1965 Voting Rights act, which remains a critical pillar in ensuring the vote today.

Alison Stewart: What is something, David, that you learned about the march in Selma that surprised you or you hadn't seen raised before?

David Greenberg: I think one thing that was surprising was just to see how political it became. I think the school book, storybook version we often get of some of these dramatic moments focuses on the heroism, the triumph, which of course should be spotlighted. We then lose sight of some of the aspects that reveal the leaders to be human beings with rival agendas, sometimes competing egos, conflicts. To see just how much bad blood there was between SNCC and King, for example, was eye-opening to me. Then also, I think, to see how much it left SNCC without a clear sense of what to do next. This really gets to the post-Selma question.

Even that spring, they're trying to figure out, where do we go from here? John Lewis actually writes an op-ed piece for a paper called the New York Herald Tribune. It used to be one of the great American newspapers. He's trying to think through an outline, where does the movement go? One of the ideas he takes up, it's much like an idea that his mentor Bayard Rustin articulated was going into politics. African Americans grabbing the levers of power from a political office, whether it's mayor or city council or Congress, to try to make change from the inside as well as from the outside.

Alison Stewart: That was David Greenberg, author of John Lewis: A Life. The audio of John Lewis recounting his memories of Selma comes courtesy of the WNYC archives. Tomorrow we'll hear about how Lewis became interested in politics. His wife, she was his number one supporter.